Timothy Snyder: How the double occupation of eastern Europe during the second world war made the Holocaust possible

Today the focus of our conversation on Encounters is Timothy Snyder’s book, Black Earth: The Holocaust as History and Warning, the Ukrainian translation of which was recently issued by the Medusa publishing house. My guest today is the scholarly editor of this publication, Volodymyr Sklokin, Associate Professor of history at the Ukrainian Catholic University.

Volodymyr Sklokin: This book is about the Holocaust, that is, about the mass destruction of the Jews during the Second World War. In fact, this is the first global synthesis of the history of the Holocaust to come out in Ukrainian. By “global” I mean that in this book Snyder is talking not just about what happened on the territory of Ukraine but about the Holocaust everywhere in Europe.

Iryna Slavinska: In fact, this history is placed in the context of several countries, if I understand correctly.

Volodymyr Sklokin: Many countries, although the main focus is the Polish and Ukrainian lands, since the majority of Jews were exterminated precisely on the territory of contemporary Poland and Ukraine.

Iryna Slavinska: If we continue this conversation, going from the superficial to the profound, it is probably worthwhile commenting on the title of this book; the metaphor of black earth, which forms the title. To what does it refer? What is worth remembering about this book? What is this black earth?

Volodymyr Sklokin: I confess that this was a mystery to me. When I first saw [it], I thought, on the one hand, that this is a metaphor of our chornozem, obviously the Ukrainian one; on the other, that this is a metaphor of black earth that is soaked in the blood of murdered Jews. During my dealings with Snyder, he explained another dimension of this metaphor to me. Here we are talking about Earth, with a capital E, about Earth as a planet and about this planet’s dimension of disease, and the Holocaust as the main symptom of this disease.

Iryna Slavinska: This is not the first metaphor that refers to land or, rather, lands. I think that our readers may have at least heard, if not read, the well-known book Bloodlands by Timothy Snyder. To what extent is the subject that was raised in Bloodlands—in particular, the territory of Ukraine in the maelstrom of the Second World War—continued in this book, Black Earth?

Volodymyr Sklokin: Yes, it is an obvious continuation. And many readers viewed Black Earth as a sequel to Bloodlands. It is obvious that Snyder is developing many of his ideas that he already set forth in Bloodlands, which has become a bestseller. Here, nevertheless, the main focus is on one tragedy, the fate of the Jews and the various contexts that made the Holocaust possible. Therefore, this is a narrowing of issues to a single topic, but one that is nevertheless a key one, at least from the standpoint of Snyder and many other historians, because Snyder believes that the Holocaust is in fact the central event of modern history. And that is why this book may be more important. Obviously, it is also more theoretically sound in comparison with Bloodlands.

Iryna Slavinska: What are Snyder’s main lines of research? After all, discussions of the Holocaust can develop in any direction, since there are so many problems and subjects that can claim one’s attention.

Volodymyr Sklokin: Clearly, unlike in Ukraine, in the West the Holocaust is a well-researched topic; it is discussed a lot in the public sphere. It is very difficult to say something new.

But in this book Snyder tries not just to summarize the research that was done before him. As is always the case, he wants to be original, and he proposes an original thesis. His main, and original, thesis is that the earlier, dominant trend that existed in scholarship for the purpose of explaining the causes and essence of the Holocaust is a mistake. That trend viewed the Holocaust as a unique and autonomous event in modern history—perhaps the central event of modern history, and it saw the Holocaust as a natural consequence of a decadent modernity, that is, the period of history that begins in the Age of Enlightenment.

Iryna Slavinska: And as a singular milestone. Here one can mention Adorno’s winged words about the impossibility or, rather, the question of whether poetry is possible after Auschwitz.

Volodymyr Sklokin: Yes. In fact, Snyder polemicizes with [Theodore] Adorno a lot. Adorno and [Max] Horkheimer put forward the interpretation that the Holocaust was the consequence of this omnipotent, bureaucratic state that was generated by the Enlightenment, the consequence of rationalism, scientism, and that Auschwitz, as a concentration camp in Poland where Jews were exterminated with such cold rationality by the modern German bureaucratic state, with the aid of contemporary technologies, was a natural consequence of a degenerate modernity that, after all, led to this. Snyder says no. His main thesis is that it was not the bureaucratic state which caused the Holocaust but the lack of a state.

Iryna Slavinska: What does this mean? Let’s decode this thesis.

Volodymyr Sklokin: He focuses on the space of the so-called double occupation. This is mostly the territory of today’s western Ukraine, but not just this territory but also Poland and the Baltic countries, and Belarus as well. During the Second World War these expanses were doubly occupied, that is, first, the Soviet occupation of 1939–41, and later the German occupation of 1941–44.

In Snyder’s view, the double destruction of the state—at first, by the Soviet government, later, by the Nazis—became the context that made the Holocaust possible because the Holocaust began precisely here; it claimed the most Jewish lives precisely here. I am saying that the destruction of the state deprived the Jews of legal and other types of defense that state institutions grant to their citizens.

Iryna Slavinska: I will pose the following clarifying question right away. During the Soviet and German occupations, these institutions supposedly existed, correct? Constitutions existed, some kinds of power institutions that were found locally. Even if it was an occupying power in certain gubernias or certain commandants, it existed at any rate. In the given context, what does the lack or absence of a state signify?

Volodymyr Sklokin: That is precisely the question: Did it exist?

Iryna Slavinska: Formally. At any rate, some institutions existed.

Volodymyr Sklokin: Yes, but the point is that when the Holocaust began and was taking place, these were in fact stateless territories, and real power there was in the hands of military administrations. And that is why the Jews, Ukrainians, and Poles, who lived in these territories, were in fact not citizens of any state. In other words, they were deprived of protection afforded by these institutions. Hence, in theory you could do anything with them.

But Snyder’s most important thesis is that even German soldiers, for example, who could not imagine that it was possible to behave this way toward their fellow citizens, even if they were Jews, in Germany, on the territory of Germany, because there was a different context there, they understood that there are laws, there are some standards, let’s say. But when they ended up in this zone of statelessness, they could begin to kill, and kill en masse, and kill women and children. And that is precisely what happened. This pertains not only to German soldiers but also to local residents, who began to do things in the situation of the double occupation which in the majority of cases they would never have done in ordinary normal life.

Iryna Slavinska: But, pogroms took place in particular on the territory of Ukraine, which was then part of the Russian Empire, even before the Holocaust and before the Second World War.

Volodymyr Sklokin: Yes. But this is not in comparative terms. The issue there was about individual victims or dozens of them. Here we are talking about mass, systematic killings, and this is also an important thesis of Snyder’s. He polemicizes with the point of view that is also widespread in the West: that the cause of the Holocaust was antisemitism, which is characteristic of some nations. Poles and Ukrainians in particular are mentioned frequently, and of course Germans. According to stereotypes, Poles and Ukrainians are traditionally the most antisemitic nationalities.

Iryna Slavinska: I think that Lithuanians are also mentioned in this context. I remember that the first image which visitors spot when they enter the Yad Vashem Museum is a large photograph of scenes of the Holocaust in Lithuania.

Volodymyr Sklokin: That’s right. Poles, Ukrainians, and Lithuanians. And Snyder polemicizes with that. He says that research demonstrates that fewer Jews died in countries with the highest level of antisemitism before the war than in those countries where the level of antisemitism was significantly lower. This is a paradox. The reason is that antisemitism in and of itself was not the cause of the Holocaust. It was only one of several factors. Nevertheless, in Snyder’s view the main reason was, first of all, the existence of this context of the zone of statelessness, and within this context German-Hitlerite ideology, which considered the Jews as the principal enemy, fused with local factors and various elements, like the political aspirations and grudges of the local population. If we are talking about Ukraine, these are the Ukrainian nationalists from the OUN, who sought, with Germany’s help, to build their own state, and thus they often carried out what the Germans expected of them. And this was complicity in the Holocaust.

Iryna Slavinska: What other principal characters, besides Hitler, who has already been mentioned, figure in this research? Any big or smaller names, perhaps?

Volodymyr Sklokin: Well, obviously, a lot of attention is devoted to Hitler.

Iryna Slavinska: As an ideologist.

Volodymyr Sklokin: Yes, he was the central figure. But Snyder talks a lot about the principal characters that are very unexpected, it would seem, in the history of the Holocaust. He talks about politicians, bigger politicians and lesser-ranking politicians of interwar Poland, the Polish state. In Snyder’s opinion, what happened in Poland was the main focus for understanding the subsequent course of events during the war. Thus, he talks about the many Polish politicians who, in various ways, wanted to solve the Jewish question, which was also important for Poland because Jews made up nearly one-third of the population. Hence, about those who tried to be pro-Zionists and to foster the Zionist movement, resettlement, the creation of the Jewish state, and about those politicians who sought to resolve these problems inside Poland, and about antisemitism, which was widespread in the interwar Rzeczpospolita. That is why Snyder’s focus is on interwar Poland, but together with the Ukrainian lands, with Galicia and Volyn, which were part of the Rzeczpospolita at the time.

Iryna Slavinska: Does Snyder answer the question of why the Holocaust became possible in general? We have already begun talking about the lack of statehood and the double occupation that made this terrible event possible.

Volodymyr Sklokin: This is part of one of the book’s main messages.

Why? The book begins with Hitler; the first chapter is devoted to an analysis of Hitler’s ideology. On the one hand, Snyder is reading well-known texts, like Mein Kampf and other works by Hitler. But he often attempts to draw attention to things that were not previously emphasized. It is obvious that Hitler was an antisemite, and much has been written about this, much discussion has taken place. But here, too, Snyder looks in a new way at the role of this antisemitism in the general system of Hitler’s views and particularly at what Snyder calls, characterizes Hitler’s ideology as a vision of a planetary ecosystem, in which a struggle among races is taking place for limited natural resources and especially for territory and for goods, foodstuffs that make possible the existence of these races. In other words, in Snyder’s view, Hitler was a kind of zoological anarchist. He viewed the history of mankind as a competition among species. In principle, this was nothing unusual for the times.

Iryna Slavinska: Sort of like an “improved” Darwin.

Volodymyr Sklokin: Yes, an improved Darwin. In fact, for him the main thing was the blessing that he called “living space,” the possibility of access to those territories, to food, Lebensraum for the German race, the Aryan race. Accordingly, the way to achieve this was by capturing new territories or exterminating or removing those peoples or other races who were in those territories for the German race. And in this world perception of Hitler’s, the Jews occupied a special place because they were not one of the competing races, but were, rather, an anti-natural anti-race in Hitler’s view. Why? Because they were convincing other people of the fact that life on earth is not a biological struggle for survival, and it is…. They base themselves on certain universal categories and values, such as ethics, let’s say, like knowledge. In other words, a certain framework proposing that a human is more than just some kind of biological entity. And thus, according to Snyder, Jews are [viewed by Hitler as] a primary danger leading the world to decline.

Iryna Slavinska: Snyder cites Hitler’s views on the “Jewish conspiracy” that comes up with this whole humanitarian framework that does not allow the races to struggle as required.

Volodymyr Sklokin: Yes, absolutely. Jews are a main danger leading the world to decline. So, for Hitler the removal or extermination of the Jews is a guarantee that this struggle among species can continue, and the Aryan race will be able to achieve dominion. In fact, this is the main cause of the Holocaust.

Iryna Slavinska: This is a circuitous reason. It still does not answer what is certainly the most naïve of questions. How can it be that some people take weapons or other devices, like gas chambers or other things, and go off to kill such a large number of people?

Volodymyr Sklokin: This is what everything began from; the introduction, so to speak. This is the vision of Hitler, who became the leader of a state that started the Second World War. And І must say that up to a certain time, Hitler didn’t even tell the Germans about his plans for such a solution to the Jewish problem. And the fact that the Holocaust happened was possible at the beginning of a colonial war for living space. The fact that the war began with an attack on Poland on 1 September ’39—this was a colonial war for the expansion of living space for the Aryan race. But during the course of the war, the logic of the war itself, this double occupation [took place] in the territories of Poland, Ukraine, and the Baltic countries, and [there was] the interaction, let’s call it, between this Nazi ideology and policy, which we were just talking about, and local conditions, particularly with the existence of certain political groups in these territories, which were interested, on the one hand, in cooperation with the Nazis, and, on the other, in either revenge or salvation of this cooperation with the communists in 1939–41. In Snyder’s opinion, it is precisely this, generally speaking, that made the beginning of the Holocaust possible in 1941, here, on the territory of Ukraine and Poland, and its later expansion everywhere in Europe, which was under Germany’s control.

Iryna Slavinska: Here, perhaps, it would be worthwhile to draw attention to the other part of the book’s title: The Holocaust as History and Warning. In the preceding conversation we discussed the historical dimension. How about we approach the history of the Holocaust as a warning. Clearly, this are Snyder’s statements about the present time and, perhaps, even the future.

Volodymyr Sklokin: Yes. In fact, Snyder’s specifics, which, I think, are familiar to many in Ukraine, are that this is not simply a historian who is researching what happened. This is also a public intellectual who is trying to see how what happened continues to influence our present day and shapes our future. This book is a fine example of this type of approach. There is a final part that is called “Our World,” which is devoted to an analysis of how an incorrect understanding of the Holocaust does not allow us to see adequately those challenges and threats that the contemporary world is facing.

Iryna Slavinska: What are these challenges and threats? Let’s present them.

Volodymyr Sklokin: First of all, those fears, yes, phobias of Hitler’s about which I have already talked a bit, his, let’s say, ecological vision of the world as a struggle for limited resources, remains present in the contemporary world; for many people, because resources remain limited. The problem of hunger, the lack of food, which was one of the key ones for Hitler, and the capture of Ukraine, for example, was an attempt to solve this problem. Yes, this remains topical. And Snyder, for example, draws attention to the fact that there is a danger. There have already been such examples, like Rwanda, where there was a horrible genocide in the 1990s, also connected with this problem, that there are limited resources there, a struggle for food, one tribe exterminating another tribe.

Iryna Slavinska: This is a post-colonial struggle that began during the era of colonialism, and was encouraged by the colonial power.

Volodymr Sklokin: Yes. These problems remain, and these challenges remain. And the danger resides in the fact that, as Snyder says, one can attempt to solve a problem as incorrectly as Hitler began to resolve them. What was the problem of Hitler, in Snyder’s view? It was that he mixed knowledge with ideology and politics with ideology, with his vision of a biological universe. In fact, he thus denied both knowledge and politics as such, and left only his biological vision of the struggle for survival. But in reality, those problems that were so important to Hitler, for example, solving the food problem, they could have been solved during that very period, and they were beginning to be solved with the help of science, for example, by increasing crop yields. Indeed, this path can be taken right now. And Snyder says that it is very important to preserve this autonomy of knowledge from politics, ideology, and the autonomy of politics, say, from knowledge and other spheres. In other words, this is the first thing that he emphasizes.

The other thing is what pertains directly to Ukraine, what we are seeing: the return of certain practices connected with the Holocaust. This is the attempt to ethnicize conflicts and to essentialize certain ethnic identities. What Hitler used as a justification for the annexation of, say, Czechoslovakia in 1938 was the same thing that Putin did in order to justify the annexation of the Crimea in 2014.

Iryna Slavinska: [Snyder is] talking about the Russian-speaking population in Ukraine, for example.

Volodymyr Sklokin: Yes. Here Snyder says that it is very important to avoid the essentialization of ethnic identities and generally all conflicts. From this angle of view, this book is a good warning about how the situation can develop further in Eastern Europe. Clearly, it was being written during the very same period when this whole situation was already developing in Ukraine in 2014. I had the opportunity then to speak extensively with Snyder. I saw the appearance of these zones of statelessness in Ukraine after the Maidan, in that short period when there was a lack of government power. Current events helped Snyder to look differently at the events of the Holocaust. The Holocaust helps us to see better what was taking place in Ukraine in 2014, why in that brief period people in eastern Ukraine began to behave in a way they would never have behaved if there had been state power, if the police there had worked like it had always worked. In other words, a lot of things would simply never have happened. But that brief period took place; so, what happened happened.

Iryna Slavinska: In Snyder’s opinion, were lessons drawn after the tragedy of the Holocaust? Looking at the contemporary world, perhaps it is centered on the experience of the United States, perhaps on the European or Ukrainian experience. We have already mentioned Ukraine in the context of his reflections.

Volodymyr Sklokin: If we are talking about the West, and Snyder acknowledges this, many lessons have been drawn and much has been done to commemorate the Holocaust in order to remember the Holocaust, so that it will remain a kind of orienting point to ensure that nothing like that will ever happen again. Never again.

But, in Snyder’s view, there are certain things that are nevertheless inadequately conceptualized. And they are not allowing us adequately to see certain contemporary challenges in the West. I have already talked about them.

If we are talking about the Ukrainian context, the situation here is different. Here even limited lessons, in fact conclusions about what happened have not been drawn yet, and even on the level of comprehending what really happened and what the involvement was, the role of Ukrainians or various groups of the Ukrainian population in the Holocaust. It cannot be said that the final point has been made and we can offer all sorts of final answers, right? Contemporary research permits us to state that Ukrainians were not only victims of Nazi policies. Likewise, they were not just Righteous Among the Nations, who only rescued Jews during the Holocaust. Some Ukrainians took part in exterminating Jews by various means: some gathered and brought them to those places, fewer took part in the shootings there, some took part in pogroms. And a proportion of Ukrainians later availed themselves of Jewish property or various other methods stemming from the consequences of the Holocaust. Therefore it is obvious that we…and I hope that this book will serves as a stimulus, so that this topic will become even more of a central topic of scholarly research, of public discussions. Because until such time as we conceptualize it and take responsibility for what happened, it will be very difficult to build a healthy society and have an adequate perception of the challenges that we are facing today.

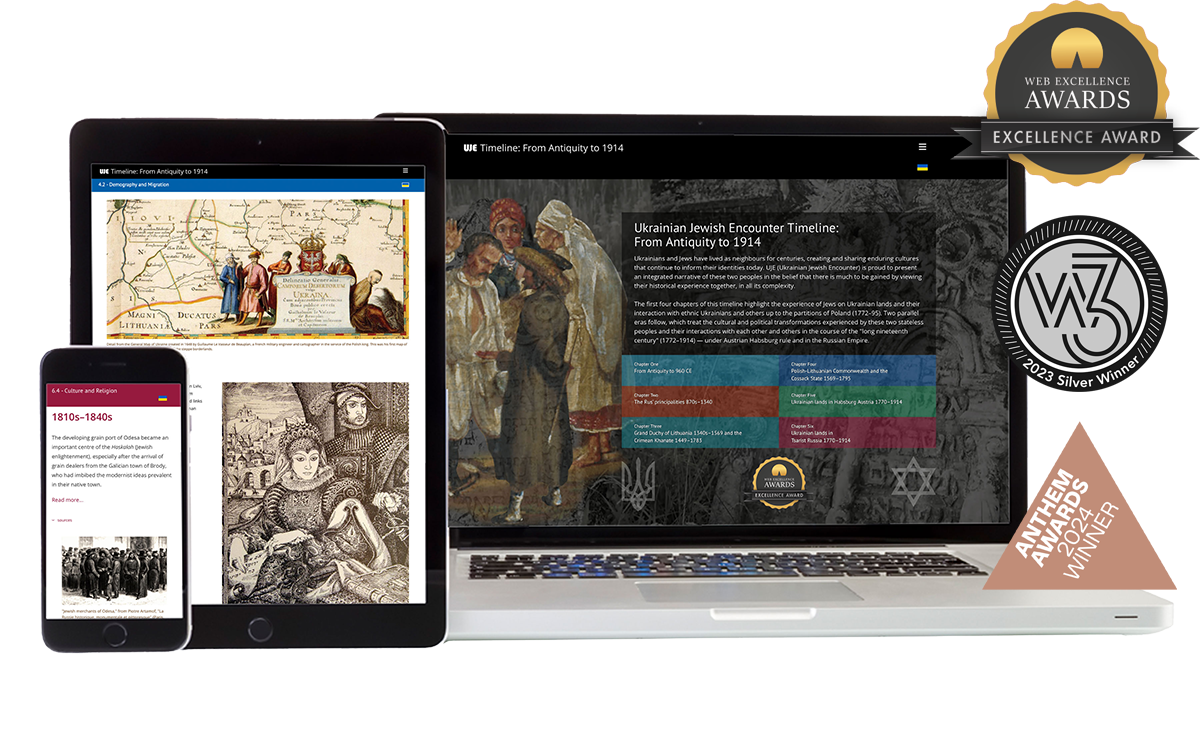

This program was made possible by the Canadian non-profit organization Ukrainian Jewish Encounter.

Originally appeared in Ukrainian (Hromadske Radio podcast) here.

Translated from the Ukrainian by Marta D. Olynyk.

Edited by Peter Bejger.

NOTE: The UJE does not necessarily endorse opinions expressed in articles and other materials published on its website and social media pages. Such materials are posted to promote discussion related to Ukrainian-Jewish interactions and relations. The website and social media pages will be places of information that reflect varied viewpoints.