The emergence of Ukrainian-Jewish identity: Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern and his new book

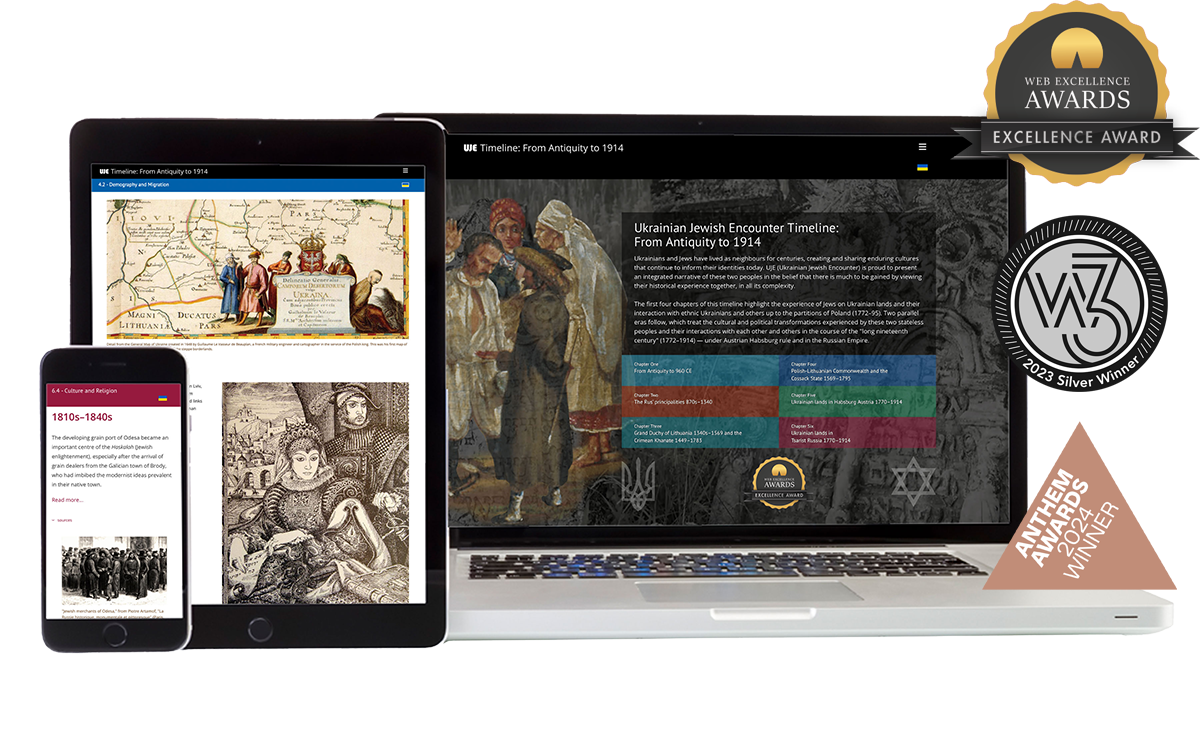

On today’s edition of Encounters we are talking with the scholar and professor of Northwestern University, Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern, about his book The Anti-Imperial Choice, which appeared recently in a Ukrainian translation published by Krytyka Press. The English-language version originally appeared in 2009.

Iryna Slavinska: How would you explain what your book is about to a person who has never encountered this topic?

Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern: This book is about boys and girls from Russian- and Yiddish-language families that decided, for reasons that I wanted to discuss in this book, to turn to Ukrainian culture, Ukrainian literature, to become Ukrainian writers. And they did this. The book examines this phenomenon as a certain process that begins in the 1880s, that is, at the end of the nineteenth century, and which is continuing to the present day.

Iryna Slavinska: This is very interesting because there is a view of the history of Jews in Ukraine, an idea that Jewish culture as an oppressed culture has the attribute of assimilating with a great culture, for example, Russian culture, if we are talking about Ukraine as a colonial country, then the idea to associate oneself with the Ukrainian language, with Ukrainian culture, does not seem to be the most typical choice.

Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern: I would say that this is not simply the most untypical but purely an anti-typical choice. This is not simply an anti-imperial choice but the choice of a culture that people of that era regard as third-rate, antisemitic; of course raped in every sense of this word, which is situated somewhere on the margins of European culture. Absorbing oneself in such a culture, seeking the possibility of becoming someone in such a culture is not “comme il faut,” absolutely not cool. But it was precisely this choice that interested me.

We are very much aware of Jews who speak the German language in the Czech lands in the late nineteenth–early twentieth centuries and seek opportunities to be absorbed into German-language culture. In Berdychiv or Odesa during this same era they are assimilating into the Russian culture. The list can be continued....

I was interested in people who, for certain reasons, wanted to choose a colonial culture for themselves. Why? What does it give them? What do they give to it? I examine these very questions here.

Iryna Slavinska: Obviously, in the context of the late nineteenth century Ukrainian culture does not look very attractive; you have already outlined several possible epithets. But to my mind, the Russian culture in the Russian Empire could appear to be equally antisemitic—which it was, in fact. And, for example, the German or Polish cultures in the Austro-Hungarian Empire were also not the most favorable for the Jewish population in the empire.

Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern: Precisely. But there is a lot of everything in imperial cultures. If we are talking about Russian culture, a certain very powerful tradition of philosemitism had formed in Russian culture by the late nineteenth century, and this tradition examines Russian–Jewish relations, the acculturation of the Jew into the Russian milieu, etc., in a more nuanced fashion, not just negatively. The same thing exists in German literature, in French, in Italian, in English...

There is very little of this in Ukrainian literature. There are problematic moments when the Jew enters Ukrainian culture, Ukrainian literature with ambivalent traits, but a powerful philosemitic tradition that existed in Ukrainian literature—excuse me, I am not aware of this.

Iryna Slavinska: Then let’s move on to the main question to which, as far as I understand, you tried to provide an answer: What was it about Ukrainian and Ukrainian-language culture that attracted those artists about whom you write?

Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern: I think that in each case we have to examine concrete situations.

I discuss Hryhorii Borysovych Kerner, a kind of millionaire from the sloboda [(tax)-free settlement—Trans.] of Huliai-Pole, who decided to turn himself, not into a Kolomoisky, but a new Ukrainian–Jewish Shevchenko. I discuss a person from a Russian- and Yiddish-speaking family in Chernivtsi, who also decided to become, not a Friedman, but a Ukrainian Symonenko. For them this is an important choice and an important point.

What are they searching for in Ukrainian literature? I think they are looking for themselves, oppressed Jews who do not have a full-fledged existence either in their own culture, which is absolutely suppressed in the Soviet period and socially suppressed during the period of the Russian Empire. They are seeking a possibility to find themselves in another oppressed culture and to become something in this culture, in order to shore themselves up and reinforce this culture. This is an encounter between two colonial moments, two colonial milieus, languages, traditions, and world perceptions. And some very interesting points come out of this. The people who absorb themselves in the Ukrainian intelligentsia milieu are not searching for an opportunity to rid themselves absolutely of Jewish traits, as this is done, for example, by Albert Camus, when he is searching for a place for himself in French culture, or as Franz Kafka does this in searching for a German-speaking environment for himself.

These are people who are creating something new and very important in Ukrainian culture; specifically, dual identity. And these dual identities are manifested in literature, in belles lettres, in poetry, in prose, and other texts. With the help of these texts, I am trying to delineate the issue of dual identity, dual loyalties that offer the possibility of introducing the Jewish tradition into Ukrainian literature and to make the Jewish tradition Ukrainian-speaking. This is absolutely an outstanding matter.

Iryna Slavinska: Now I would like to ask you again whether those artists, at the moment they are attempting to acquire a Ukrainian-speaking Ukrainian identity, are thinking about Ukrainian culture as an oppressed one. This often happens in empires, where minorities seem as though they are competing to determine who is more oppressed. When you belong to the oppressed Jewish minority, it is not so easy to perceive that people from another minority, for example, Ukrainians, are also suffering, experiencing persecution.

Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern: Look, one of my heroes, one of the five heroes in this book, is Izrail Yudovych Kulyk, who was born at the beginning of the twentieth century in the city of Uman. At a certain moment he considered himself a person who has to make a contribution to the development of Ukrainian artistic culture. He travels throughout the countryside and paints Ukrainian cutouts, Easter eggs. Incidentally, his sketches from 1908, 1909, and 1911 have been preserved.

And later he delivers a lecture at the Uman branch for the protection of monuments, and this lecture is reported by the newspaper Rada in Kyiv, which, as we know, was sponsored at the time by [Yevhen] Chykalenko; it was one of a handful of Ukrainian-language newspapers at the beginning of the twentieth century. And they write that in Uman someone named Kulyk delivered a lecture about Ukrainian folkloric ethnographic monuments. And that’s it, maybe all of three lines, but behind these lines stands—get this—the 14-year-old Izrail Yudovych Kulyk, who became Ivan Yuliianovych Kulyk. He writes collections of Ukrainian poetry, one after the other, translates the rhythms of American musical folklore into the Ukrainian language, creates the first Ukrainian anthology of American poetry...

Iryna Slavinska: Why this simulation à la Ivan Kulyk? Why should Izrail Kulyk transform himself into Ivan?

Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern: You know, I devoted five pages to this in the book, and I am not sure that I can retell and paraphrase this right this minute. He seeks a Ukrainian identity for himself. And he seeks opportunities to be a Ukrainian writer, a poet, a personality. He founds Hart in Canada, he founds several other proletarian literary organizations, proletarian literary organizations in Kharkiv, in the latter half of the 1920s.

When he arrives in Kharkiv in 1917, he joins the Ukrainian Bolsheviks—excuse me for using that term but you can’t avoid it. He is asked by [Volodymyr] Zatonsky or some other Kharkiv-based Bolshevik to deliver a speech to a Cossack regiment that is hesitating about whether to join the forces of the Central Rada, or to remain with the Ukrainian Bolsheviks or to go with the Moscow Bolsheviks. And this small, ginger-haired man with freckles, Izrail Yudovych Kulyk, that is, Ivan Yuliianovych Kulyk, greets the Cossacks, talks with them, and they make him the head of this Cossack detachment. These are semi-anecdotal situations, but there are many of them in my book.

Iryna Slavinska: We have twelve minutes left to become more acquainted with the heroes and heroines of this book. I will name them for our listeners: Hrytsko Kernerenko, Ivan Kulyk, Raisa Troianker, Leonid Pervomaisky, and Moisei Fishbein. I think it is worthwhile to become more closely acquainted with each of them, but first I will ask this general question. For these five heroes about whom you write, was their entry into Ukrainian culture an entry into the Ukrainian language as well? Did they study it, acquire it, work with it?

Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern: This is a very interesting point. All of them studied the Ukrainian language.

Before Hrytsko Kernerenko [becomes] Hrytsko Kernerenko, he is living in the 100-percent Russian-speaking milieu of Huliai-Pole. Since he is of Jewish background, he cannot get into a university in Odesa, Kyiv, St. Petersburg, or Moscow even with money because sometimes Russian officials don’t take bribes. But there exists numerus clausus, that is, only one percent of Jews will be accepted into a university, and the rest have to go somewhere else.

That’s why he goes to Munich, he studies how to work with engineering, he learns how to deal with things connected with agricultural matters because his father, Borys Kerner, in Huliai-Pole, is a [farm machine] factory owner. And he goes back, begins writing Ukrainian books, begins writing Ukrainian poetry, prose, plays, tales. And, of course, for him the Ukrainian language is an acquired Ukrainian language. He reads quite a lot, orders books from Kyiv. And one of the very famous writers of the twentieth century in the diaspora writes a memoir about how in the late nineteenth century he remembers that in Huliai-Pole the only possibility to read Ukrainian books was to borrow them from Hrytsko Kernerenko.

Iryna Slavinska: He functioned as a kind of public library?

Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern: Absolutely. Take note: a Ukrainian public library. I can continue these examples.

Of course, there is the fascinating example of Raisa Troianker from Uman. She grew up in a Yiddish-speaking environment, she had a traditional Jewish family. As we remember, in the late nineteenth century 97 percent of Jews in the Pale of Settlement spoke Yiddish. She knew the Russian language very well, she loved Russian poetry, until the end of her life somewhere in Murmansk she carried around with her a small volume of [Anna] Akhmatova’s poetry and a small volume of [Nikolai] Gumilev’s poetry. Nevertheless, she started out in the Ukrainian language because she fell in love with [Volodymyr] Sosiura.

Iryna Slavinska: It would be interesting to know how she read Sosiura. She fall in love in the primary sense of the word?

Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern: I don’t want to stoop to the level of the tabloid press, but she fell in love in the primary sense of the word. This was her second love. Her first love was when she was fourteen-and-a half years old. She fell in love with a circus performer who came to Uman. He took her into his act and she performed that remarkable number where she had to put her head into the mouth of a tiger. And this is exactly what she did. That was her first love and it was a Russian-language love.

Her second love was Sosiura. Under Sosiura’s influence, she began to write her poems; later, under Valerian Polishchuk’s influence also, when she arrived in Kharkiv and enrolled in teachers’ courses at the teachers’ institute and began to be published in various Ukrainian literary journals and newspapers, and to write Ukrainian poetry.

Iryna Slavinska: How did she learn Ukrainian? In Ukraine today there are, for example, free or paid courses—depending on the context—for those who want to learn it. Were there places like that in Uman in those days or, perhaps, in Kharkiv, where you could go and study the language?

Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern: I think you’re joking. There was no such place. You could learn the language either from books or from direct communication, and this was mainly in a village setting. I know, for example, that Ivan Yuliianovych Kulyk when he was still Izrail, Srul, Kulyk was dashing to Sofiivka Park and playing Cossacks and bandits with the little boys that came from the surrounding villages. He learned the Ukrainian language from them. And he recounts this in the unfinished poem “Sofiivka.” In the uncompleted poem he describes his encounter with the Ukrainian language, with the little boys from Ukrainian villages who were the carriers of the language. And I think that for many of the heroes in my book the language was acquired. There were cases where these people were baited during episodes of state antisemitism in the Soviet Union.

Iryna Slavinska: Because of the Ukrainian language?

Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern: For example, Illia Shliomovych Hurevych, who became Leonid Pervomaisky, was subjected to attacks by Mykola Sheremet; he was a Komsomol poet about whom Pervomaisky wrote back in 1927: “Sheremet is a poet? Not a poet is Sheremet!” In 1957 Sheremet decided to write a few vile articles and launch a polemical attack against Pervomaisky at a meeting of the Union of Writers. And he accused Pervomaisky of being not a nightingale but a “foundling,” and that under the mask of a Ukrainian poet he was hiding his shameful being as a rootless cosmopolitan. And Pervomaisky gave an extraordinarily strong response to him; there are ten pages about this in the book.

Iryna Slavinska: Perhaps you can provide us with a “spoiler” and tell us how he responded.

Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern: For that I would have to take the book in hand and read aloud. I have some interesting citations from that text. This is an eighteen-page text that is entitled “The Bread of Mr. Sheremet.”

Iryna Slavinska: Let’s talk a bit more about Leonid Pervomaisky and Moisei Fishbein. I remember that in the foreword you write about their connection, about some sort of continuity.

Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern: It was important for me not only to explore certain episodes marking encounters between Jewish boys and girls with Ukrainian literature, with the language and poetry, but also to become convinced and to convince readers—and, of course, reviewers of my book—that what I am talking about is not incidental but about a tradition.

Iryna Slavinska: In other words, a kind of continuity and exchange between generations if I can put it this way.

Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern: Of course. In each of these generations we see not just one figure. If we look at whom Ivan Yakovych Franko publishes in the Literaturno-naukovyi vistnyk [Literary Scientific Herald, or LNV—Trans.], we see that in the early 1900s Franko has several people with Jewish names who are contributing articles, poetry, and prose works as well as translations to the Literaturno-naukovyi vistnyk. One of them is Hrytsko Kernerenko.

When Troianker enters Ukrainian literature, when Kulyk begins writing his first works, and he wrote his first work in a Polish prison, it was called My Kolomyikas [Ukrainian folk ditties—Trans.], it is with these very kolomyikas that he enters Ukrainian literature. Dozens of people of Jewish background who enter the Ukrainian intelligentsia, become part of it, were grouped around Troianker and Pervomaisky. I can mention, of course, the brilliant Shevchenko specialist Yeremiia Aizenshtok and the very fine writer and literary critic Volodymyr Koriak. There are quite a few of these people. We can continue this list if we are talking about Fishbein in the 1960s. Around Fishbein are perhaps hundreds of people of Jewish background, who came into the literature, and we can speak about thousands of those who are defending Ukraine, the Ukrainian choice, the anti-imperial choice on the Maidan and in 2004. This is the context around each of them.

There are also direct ties between them. For example, Kulyk knows Troianker. Kulyk helps [Sava] Holovanivsky and Pervomaisky become established. They don’t need a shove, they are sufficiently talented people, but it is he who brings them into the VUSPP [All-Ukrainian Union of Proletarian Writers—Trans.] and helps them enter Ukrainian literature, introduces them to editors of various journals. At the end of his life Pervomaisky meets Fishbein. We see this tradition. But few of these people knew about Kernerenko, and Kernerenko is absolutely a mythological personage—bigger than life, as English-speaking people say—who merits a separate monograph.

Iryna Slavinska: I remember a conversation with Josef Zissels. We were talking about the emergence of Ukrainian–Jewish identity. And Mr. Zissels referred in particular to the experience derived from the work of dissidents, the experience of cooperation among circles of people who were accused of Ukrainian bourgeois nationalism and those who were accused of Zionism. Based on your research, can one speak of the formation of Ukrainian–Jewish identity, of Jewish–Ukrainian identity? Words can be transposed with words, but the essence will probably not change.

Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern: I think that number one this is what the book talks about. Number two is about the encounter of Ukrainian dissidents with Jewish dissidents, which helps Jewish dissidents to become dissidents with a Zionist orientation and to understand what national values are. This is my next book project, and I hope that when the book comes out, I will end up again with you in this room, and we will discuss it.

I discussed this topic in the chapter about Moisei Fishbein, showing that in fact, among these dissidents he, too, belonged to the circle of these same dissidents. The issue is Ukrainian–Jewish identity, and I think that it should be said that any culture is maintained thanks to the wealth of these dual, triple identities, who enrich this culture by bringing other ethnonational traditions to it and trying to input these traditions. In our case, in the Ukrainian context.

Recall Oswald Burghardt, who comes from a certain tradition and decides that with such a wonderful, such a beautiful, melodious name he should not add himself to the German tradition—he becomes Yurii Klen. Recall the Pole, Wacław Lipiński, who believes that he does not need to be the next Polish national romantic, and he becomes one of the three main figures in the development of Ukrainian national-political thought. In fact, in things of this kind, German–Ukrainian, Polish–Ukrainian, Russian–Ukrainian, they are very important for enriching any culture.

Iryna Slavinska: The choice of Ukrainian identity is comprehended, reflected on, and called anti-imperial, or is that your interpretation?

Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern: You know, when I was considering what to call it, about whether there was a common denominator among my heroes and in the texts written by my heroes, somehow this title came very quickly.

For most of them, the choice was conceptualized in non-imperial, extra-imperial, or anti-imperial terms. It was a choice of national-democratic culture, not the culture of a titular nation, which is connected with the Russian language, with institutions of violence. This is an important aspect; it’s about associating and identifying with victims. This is brilliantly conveyed by Pervomaisky, brilliantly conveyed by Fishbein. My other heroes approached this theme by various approaches.

When Kernerenko says that he is being hounded, that he is not accepted in the Ukrainian environment, that people laugh at his awkward Ukrainian language, he declares: “My Ukraine, I will love you for a lifetime, because even though you are my stepmother, you are still a mother to me.” You must understand that for a Jew from Huliai-Pole to say such a thing in the 1880s is simply to engrave this for all eternity. This is a very important step, and we still have to make a genuine assessment of his ethnic dimensions, his cultural dimensions.

This program was made possible by the Canadian non-profit organization Ukrainian Jewish Encounter.

Originally appeared in Ukrainian (Hromadske Radio podcast) here.

Translated from the Ukrainian by Marta D. Olynyk.

Edited by Peter Bejger.

NOTE: UJE does not necessarily endorse opinions expressed in articles and other materials published on its website and social media pages. Such materials are posted to promote discussion related to Ukrainian-Jewish interactions and relations. The website and social media pages will be places of information that reflect varied viewpoints.