How the police chief of Budaniv gave up his life for the Jews

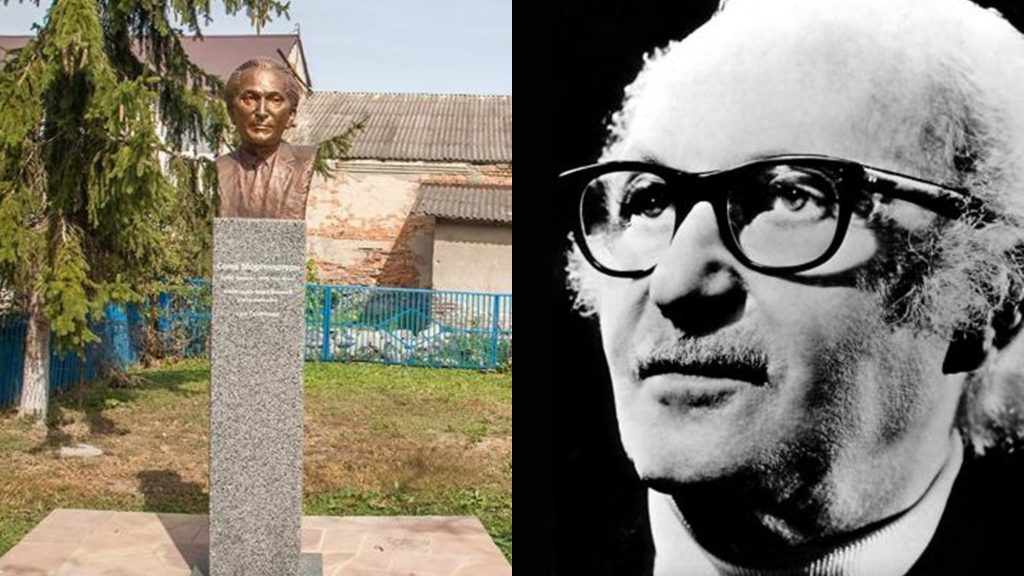

The western Ukrainian village of Budaniv (Pol. Budzanów) in the Ternopil region boasts a number of Jewish historical monuments. Recently, the traditional triad of “synagogue–Jewish development–cemetery” was supplemented by the installation of a monument to a famous countryman, the German-language writer Soma (Solomon) Morgenstern (1890–1976). Incidentally, this is the birthplace of Lee Strasberg, the founder of the famous acting school, whose students included Al Pacino, Marilyn Monroe, Dustin Hoffman, Robert de Niro, and others.

It should be mentioned that deep in the Ukrainian countryside monuments to Jewish cultural figures are a rarity. The same goes for monuments to Ukrainian figures (excluding Shevchenko).

As this Hadashot correspondent learned, in Budaniv there is another unique and absolutely unexpected monument that has a direct connection to Jews.

In the old Christian cemetery, between a medieval castle and the “New” Jewish cemetery (the “Old” one has been preserved in Budaniv), stands a small gravestone. It is standard for these places: an obelisk made out of the local red sandstone with a bas-relief in the shape of a cross. The epitaph, however, is puzzling:

“Here rests Stepan Derevianko, the chief of police of Budaniv. Died after brief, severe torments on 22 December 1941. The deceased died a hero’s death maintaining law and order.”

The fact that the monument to a police chief during the German occupation was not demolished during the Soviet period is already remarkable. The deceased clearly enjoyed the respect of his countrymen, since the locals did not leak any information to the authorities.

I will digress a bit here. It has long been known that generals always prepare for the next war—and not just generals.

Today we are all strong in hindsight, but in 1941 most Ukrainians perceived the German-Soviet war as an analog of the Russo-German war of 1914–1918. Even in eastern Ukraine, many people were awaiting the disciplined, respectful, and cultured Germans, who would chase out the communists and introduce order. But Ukrainians aside, the myth of the civilized Germans circa 1918 was kept alive tenaciously even by elderly Jews.

Western Ukraine was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire until 1918. After the Anschluss, many Galicians viewed the citizens of the Third Reich as practically “their own people.” Moreover, until recently the Germans had come here as allies. In the summer of 1917, it was the Kaiser’s soldiers who helped rid Galicia of the Russian troops, who gained notoriety by their robberies, looting, and senseless repressions.

Thus, in the summer of 1941, the Ukrainian population did not consider the Nazis as their enemies. Furthermore, the first stage of the German occupation was much “milder” than the Soviet occupation or, occasionally, the Polish one (of course, this did not apply to Jews, in contrast to Ukrainians).

Is it any wonder, then, that many Ukrainians viewed working for the occupying authorities as the first step toward establishing Ukrainian statehood? When the futility of these hopes became obvious, some joined the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA), while others were killed by the Nazis.

All of the foregoing in no way whitewashes the occupation police. Its role in subsequent repressions of the civilian population during the Holocaust and in other Nazi crimes is well known and indisputable. That is why it is so difficult today to apprehend events from the perspective of the summer of 1941 when the Germans had just occupied western Ukraine.

The police chief Stepan Derevianko was one of those who wanted to serve Ukraine and protect the interests of the residents of Budaniv. And there were many forces from whom they needed protection. There were many heavily armed gangs in the area, consisting of both ordinary criminals and deserters.

One local old-timer, Yevhen Baran, said that in late 1941 the leaders of the Jewish community appealed to Derevianko for protection. Rumors had reached them that members of the underclass and criminals from neighboring villages had decided to take advantage of the Germans’ attitude to the Jews and show initiative from the bottom (and, at the same time, to engage in robbery). Their thinking was: “the new authorities do not welcome the Jews, so you can safely arrange a pogrom and make a good profit.”

The information was confirmed. A small detachment of the Budaniv police headed by Stepan Derevianko faced down a mob of pogromists on the bridge spanning the Seret River, right at the entrance to the small town. A skirmish ensued, which escalated into a shootout. Encountering armed resistance, the pogromists retreated at once, and a pogrom was averted. During the skirmish, Derevianko was mortally wounded.

Have you often heard about any policemen who were killed while defending Jews? Until now, this author never did, not a single time. Of course, this did not save the Jews of Budaniv. In November 1942 some were sent to the ghetto in Terebovlia, from where they were soon deported to the Bełżec death camp, and the remainder were shot. Derevianko never learned about this.

This is the extraordinary story hidden in the modest monument located in the ancient cemetery in Budaniv.

Dmitry Polyukhovich, SPECIAL to Hadashot

Originally appeared in Russian @Hadashot.

Translated from the Russian by Marta D. Olynyk.

Edited by Peter Bejger.

NOTE: UJE does not necessarily endorse opinions expressed in articles and other materials published on its website and social media pages. Such materials are posted to promote discussion related to Ukrainian-Jewish interactions and relations. The website and social media pages will be places of information that reflect varied viewpoints.