A forgotten hero who combined Zionism with the Ukrainian idea

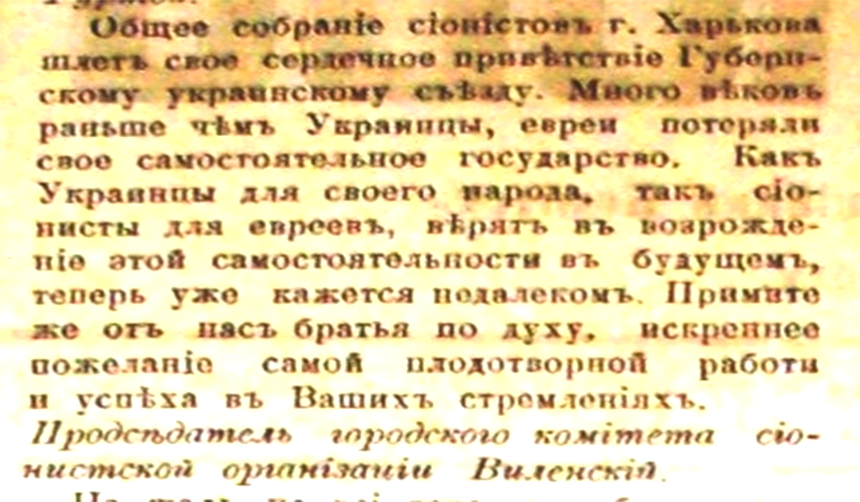

"The General Assembly of Zionists of Kharkiv sends its warmest greetings to the Provincial Ukrainian Congress. Jews lost their independent state many centuries before Ukrainians did. Both Ukrainians and Zionists believe in reviving their respective independent states in the future, which now seems not far off. Brothers in spirit, please accept our sincere wishes for the most fruitful work and success in your aspirations," read a telegram signed by Lev Vilensky, head of the Zionist organization in Kharkiv.

This welcome telegram sent by Zionists to the leading figures of the Ukrainian national revival in Kharkiv was published in the Ukrainian newspaper Ridne Slovo on 22 April 1917.

The context of this telegram is crucial for understanding its significance. A mere 50 days had passed since the collapse of the monarchy in Russia, and even the leaders of the Ukrainian movement at the time thought of nothing more than a possible autonomous status of Ukraine within the Russian republic. Meanwhile, Vilensky went a step further when he wrote about the revival of independent states — Ukrainian and Jewish — in the near future.

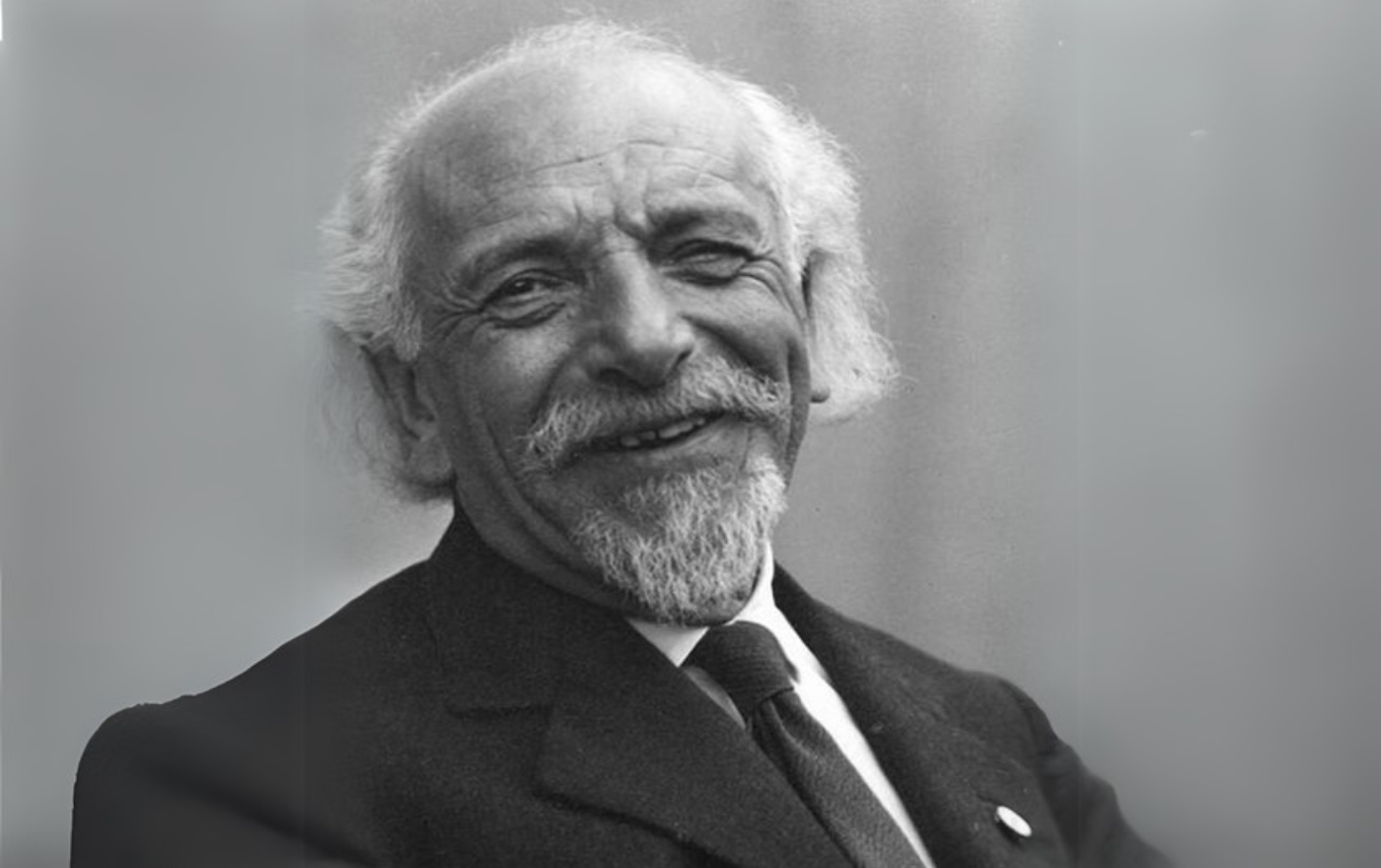

Lev Vilensky was born in 1870 in the Mogilev province into a family of rabbis of the Chabad Hasidic movement. His father, Borukh-Wulf Vilensky, soon moved to the Poltava province and became one of the founders of the Hovevei Zion (Lovers of Zion) organization in Kremenchuk.

The young Lev Vilensky studied at a gymnasium in Poltava and then at the Technical University of Berlin, eventually earning a doctorate in chemistry and philosophy from the University of Basel in 1891. Together with Chaim Weizmann, who would become the first president of the State of Israel, he created an organization of Jewish Zionist students in Berlin.

From 1897 to 1903, Vilensky lived in Kremenchuk, where he was elected a delegate to the First World Zionist Congress in Basel (1897). He subsequently participated in all Zionist congresses until the 19th.

From 1903 to 1905, Vilensky worked as the public rabbi of Mykolaiv and was responsible for registering the births, deaths, marriages, and divorces of the local Jews. He called for the abolition of the birth certificate fee for poor Jews. During the pogroms of October 1905, he organized Jewish self-defense units in Mykolaiv. In November, Vilensky sent 28 armed young Jews to Kryvyi Rih to organize a fighting squad there and went there to personally participate in the Jewish resistance. For these actions, Vilensky was dismissed from his post, arrested by the tsarist police, and sentenced to exile to Siberia. However, after a wave of public protests, he was released from prison and then lived in Berlin and Kharkiv.

Vilensky quickly gained popularity among the 25,000-strong Jewish population of Kharkiv. As an authoritative Zionist leader of international stature, he led the city's Zionist Organization. After the February Revolution of 1917, he was elected head of the Kharkiv Jewish Community and a member of the Kharkiv City Council. Vilensky led the Kharkiv Jewish Community during the most difficult time of the Civil War, from the end of 1917 to the beginning of 1920.

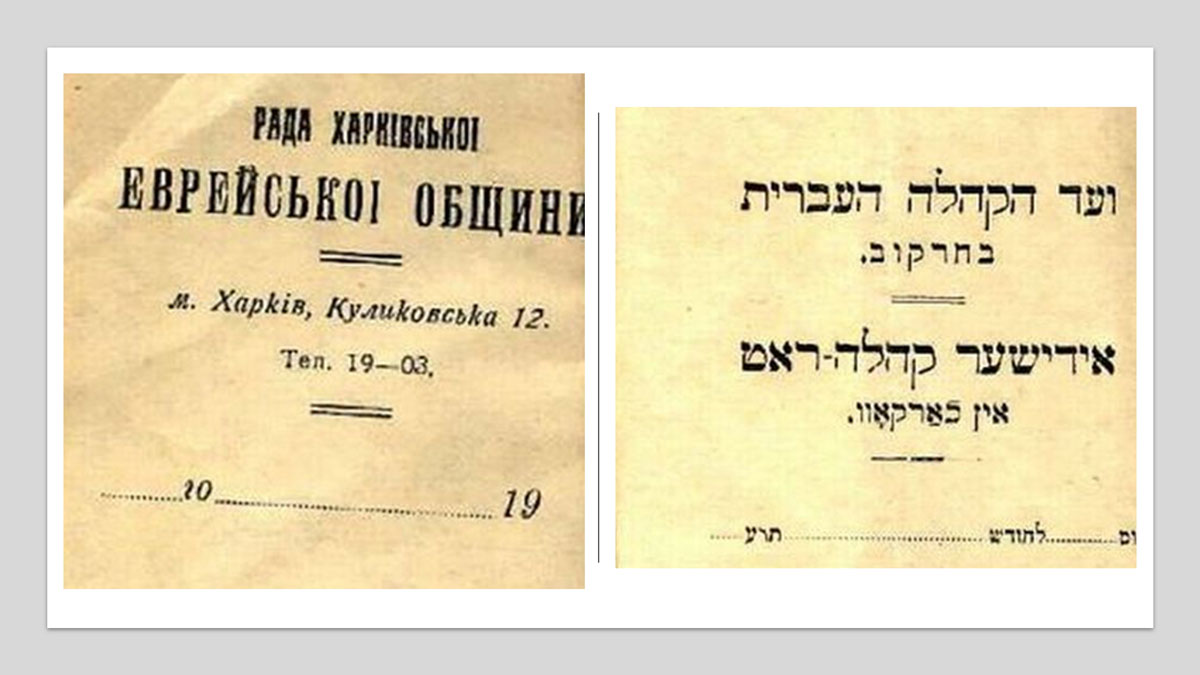

In this office, he did much to bring the Ukrainian and Jewish peoples closer together. Supporting the proclamation of an independent Ukrainian National Republic, Vilensky created new forms for the Kharkiv Jewish Community in three languages — Ukrainian, Hebrew, and Yiddish.

Vilensky corresponded with the UNR ministries and supported initiatives to develop Jewish cultural autonomy and Jewish education, which were part of the ethnic minorities policy of the UNR and the Ukrainian State under Hetman Skoropadsky. Vilensky participated in the All-Ukrainian Jewish National Congress in Kyiv in November 1918. Remembering his experience fighting pogroms in Mykolaiv, he organized well-armed Jewish self-defense units in Kharkiv that guarded the city's Jewish districts. Kharkiv did not experience pogroms despite numerous changes of power in the city.

In the fall of 1919, in the last months of General Denikin's White Army rule in Kharkiv, Vilensky received an urgent telegram from the Kyiv Jews. They asked him to help the victims of a brutal pogrom carried out in Kyiv by the Russian monarchist troops. Vilensky organized a fundraising campaign among the Kharkiv Jews, which resulted in over four million rubles being sent to the Jewish victims in Kyiv.

The Red Army entered Kharkiv in December 1919. After Soviet power was established in Ukraine, Vilensky was sentenced to death, but he managed to escape through the Caucasus and, with his family, reached the Land of Israel in 1920.

From 1920 to 1932, Vilensky successfully worked at the Keren Hayesod Foundation (Foundation Fund), which was run by his old friend Dr. Chaim Weizmann. The foundation raised money around the world to finance the creation and development of the infrastructure of the future Jewish state. For this purpose, Vilensky traveled many times to the Jewish communities of Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Romania, Latvia, Estonia, Lithuania, Finland, and Germany. Vilensky always sought to avoid conflicts between left and right groups within the Zionist movement, enabling him to become a founder of the General Zionists party. He retired from work in 1932 due to illness and moved to Haifa, where he died after surgery at the age of 65. A street in Haifa is named in his honor.

In honor of their father, his children changed their surname to Yalan based on the Hebrew abbreviation of his Jewish name, Yehuda Leyb Noson. His son Shmuel Vilensky, born in Kremenchuk, became an engineer at Israel's first power plant and was among the founders of Solel Boneh, one of Israel's largest construction companies. His second son, Amnuel Yalan-Vilensky, born in Mykolaiv, became a professor of architecture at the Technion in Haifa. Vilensky's daughter, Miriam Yalan-Shteklis, born in the village of Potoky near Kremenchuk, studied at Kharkiv University and in Berlin. She headed the Slavic Department of the National Library at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem for over 30 years and was awarded the Israel Prize for Children's Literature for her poetry in 1956.

Text: Shimon Briman (Israel).

Photo: Central Zionist Archives (Jerusalem).

Translated from the Ukrainian by Vasyl Starko