A Jewish "founding father" of Ukraine who destroyed communist rule

Yuri Haisynsky is one of the 346 Ukrainian MPs who voted to pass Ukraine's Act of Independence on 24 August 1991. That day, all five Jewish MPs supported the birth of a new state.

A prosecutor and co-chairman of the Kharkiv city branch of the Memorial Society, aimed at revealing the crimes of the Stalinist regime, Yuri Haisynsky is a paradoxical and symbolic figure. He burst onto the political scene during a turning point in Ukrainian history. In the last days of the stormy summer of 1991, Haisynsky headed the Verkhovna Rada commission to investigate the participation of Ukraine's Communist Party in the attempted coup d'état of 19–21 August. He then drafted and read in parliament the resolution to ban Ukraine's Communist Party and nationalize its property. Thus, the 44-year-old MP from Kharkiv played a key role in outlawing the Communist Party and putting an end to the government that had kept tens of millions of Ukrainians in fear and terror for over 70 years.

Haisynsky was then appointed First Deputy Prosecutor General (Ukraine's first), later joined the bar, returned to the office of Deputy Prosecutor General, and worked as the Kyiv city prosecutor.

On the eve of the 34th anniversary of Ukraine's Independence, Haisynsky, now aged 77, discusses those dramatic days, Ukrainian-Jewish relations, his life path, and the fates of Ukraine and Israel.

Shimon Briman: Thinking back to August 1991, when communist power ended and an independent Ukraine was born, did you foresee that the collapse of the old system was so close? Did you assume in the summer of 1991 that the change would lead to the complete collapse of the USSR?

Yuri Haisynsky: My critical perception of communist realities emerged much earlier. In the spring of 1989, I participated in the elections of deputies to the Supreme Soviet of the USSR in the Kharkiv district. As a result, my political views became known to many Kharkiv residents.

In March 1990, I was elected an MP to represent Kharkiv's Moscovsky electoral district in the Verkhovna Rada of what was then the Ukrainian SSR. My political views were clearly anti-communist. In particular, I proposed restoring private property and free enterprise in the country.

I had no premonition of the complete collapse of the USSR, but the collapse of the communist totalitarian system seemed imminent.

On 16 July 1990, the Verkhovna Rada adopted the Declaration of State Sovereignty, the content of which did not raise any doubts about the political intentions of its constitutional majority. The Verkhovna Rada then put a lot of effort into amending the legislation of the Ukrainian SSR. In October 1990, significant amendments were made to the Constitution, aimed at dismantling the communist system and pulling out of the USSR. In particular, Article 71 of the Constitution was worded as follows: "The supremacy of the laws of the republic shall be ensured on the territory of the Ukrainian SSR." This and other laws made it impossible to subordinate Ukraine's government authorities to the central authorities in Moscow.

What were the top leaders of the KGB, the Ministry of Internal Affairs, the Ministry of Defense, ministers, and other Moscow officials to do? Stage a coup, which is what happened on 19–21 August 1991.

Shimon Briman: How did the idea of declaring full independence take over the Verkhovna Rada? Was it scary to make decisions and vote on 24 August 1991? What do you remember about that day? Did it appear historic?

Yuri Haisynsky: The Act of Proclamation of State Independence was adopted at an extraordinary session of Ukraine's Verkhovna Rada on 24 August 1991. The protocols of the roll-call votes of the MPs have been preserved — I voted for independence, confident that Ukraine would end communism.

I did not feel fear when voting. On the contrary, the emotions were quite positive. This day was remembered as a decisive step towards historical changes in the life of the country and mine in particular.

The Act had yet to be approved at a referendum, which happened on 1 December 1991. That day became truly historic.

I often read that Ukraine's independence became possible due to pressure from the West, primarily the USA. All according to a conspiracy theory. Let me share my observations on this matter.

On 30 June 1990, British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher gave a wonderful speech in the Verkhovna Rada. When asked about the possibility of establishing diplomatic relations with Ukraine, she replied: "No. We do not have diplomatic relations with the state of California."

Then, on 1 August 1991, US President George H.W. Bush spoke in the Verkhovna Rada. He spoke against the "disintegration" of the USSR and referred in negative terms to the idea of Ukraine's independence. I was present at both speeches. I had no doubt that the issue of big politics had to be resolved by Ukraine on its own. And that's how it happened.

Shimon Briman: Why did Leonid Kravchuk appoint you head of the Commission to investigate the events of the August 19–21 putsch? How did he treat you overall? Did he know about your Jewish background?

Yuri Haisynsky: I was elected chairman of the parliamentary Commission to investigate the putsch at a meeting of the Presidium of the Verkhovna Rada chaired by Leonid Kravchuk on 26 August 1991. I don't know why they picked me. It took place in my absence. Twenty-two MPs were elected to the Commission.

Kravchuk knew about my Jewish background. I told him about it during a conversation after I was appointed First Deputy Prosecutor General. He said something like this in reply: "Yes, I know. But I don't have an anti-Jewish inferiority complex." I explained that I was telling him about it directly so that there would be no psychological problems. Kravchuk said, "There will be no problems. Do your job." Our relations were good, businesslike.

In May 1993, President Kravchuk signed a decree granting me the rank of State Counselor of Justice, 1st class, an equivalent of the military rank of Colonel General of Justice.

Shimon Briman: On 30 August 1991, your report ended the history of Ukraine's Communist Party, resulting in its ban. The party had kept the entire country in fear for 70 years. At the same time, you were previously its member and climbed the ladder of the Soviet apparatus. What did you experience in those days, as you raised your hand against the gigantic machine of the old government? Where did you get the courage to ban the Communist Party of Ukraine?

Yuri Haisynsky: I left the party on 18 July 1991, together with the secretary of the party organization. It happened at a party meeting in the prosecutor's office of Kharkiv's Moskovsky district.

I remember 30 August 1991 well. There was a meeting of the Presidium of the Verkhovna Rada. The place was packed with people standing in the aisles and sitting on the floor, but it was very quiet. For three days before that, our Commission met to study documents and question the leaders of Ukraine's Communist Party, particularly First Secretary Stanislav Hurenko.

The footsteps of history could be heard at the meeting of the Presidium. After presenting the report, I answered questions from the Presidium members, some of whom also took the floor. Finally, Leonid Kravchuk suggested that I announce the draft Decree, taking into account some comments.

I stood up and read the draft Decree, the operative part of which contained two main points:

- To ban the activities of the CPSU-CPU on the territory of Ukraine.

- To nationalize the property belonging to the CPSU-CPU in Ukraine.

Nineteen Presidium members voted to adopt the Decree, with one vote against.

The next day, Lisovenko, a member of the Politburo of the CPU Central Committee, handed me the keys to the main building of the party's Central Committee on Bankova Street, where the Presidential Office is now located. I passed these keys on to the head of the Verkhovna Rada Affairs Department.

That was the end of the CPSU-CPU in Ukraine. As it turned out, temporarily. For two years, the Communist Party did not exist in Ukraine, and then a new Communist Party was created. But that's another story.

As far as personal consequences are concerned. I realized I would have to deal with the repercussions of the Communist Party ban for a long time, possibly until the end of my life. The connections of those in power are maintained for a long time. But the ban on the Communist Party of Ukraine and the nationalization of its property were just decisions.

Our Commission also passed decisions regarding the KGB, the Ministry of Internal Affairs, and the media. The decisions were also just, but the responsibility for their adoption is on me personally.

Shimon Briman: In the first half of the 1990s, you faced an avalanche of accusations of "creating a mafia" and enrichment that appeared in the press. How prominent was antisemitism in those attacks?

Yuri Haisynsky: What concerns accusations of abuses leveled against me, I acquired many enemies after the Presidium of the Verkhovna Rada banned the activities of the CPU. CPU supporters were unhappy about the ban, while national radicals were dissatisfied that no one was punished. I have spoken and written a lot about this publicly.

Criminal cases were initiated against me and investigated for several years by the investigative department of the Prosecutor General's Office. All of them were closed for lack of corpus delicti.

From December 1993 to 1999, I worked as a lawyer and entrepreneur. In January 2000, Prosecutor General of Ukraine Mykhailo Potebenko appointed me Kyiv city prosecutor, and a little later Deputy Prosecutor General of Ukraine and Kyiv city prosecutor. In his book Searching for the Truth, Potebenko says nice things about me, which I am also proud of.

Shimon Briman: Your parents and grandparents were Jews born in Ukraine. How was your national self-identification formed? What did adults tell you? What did they hide, and how did they teach you to live?

Yuri Haisynsky: My parents were Jewish. My mother was born in Poltava, and my father was born in Kremenchuk. My grandfather, Lazar (Leyzer) Davidovich, was born in 1891 in Vilnius, Lithuania. While serving in the tsarist army in Poltava, he met my grandmother, Hanna (Haya-Leya) Herman. Their daughter, Dora Davidovich, was my mother.

My grandfather, Yakov Haisynsky, was born in Kremenchuk. He was in exile in Yakutia, where he married my grandmother, Ide (Itte) Strad, the daughter of a local rabbi, in May 1917.

My grandfather Lazar had a significant impact on my Jewish self-identification. My parents divorced when I was about two years old. I lived with my mother and her parents until I was 10. My grandparents often spoke Yiddish between themselves. In most cases, they did so that I wouldn't understand what they were talking about. They did everything to protect me from anti-Jewish manifestations.

From the age of 10, I lived with my father and stepmother Nadia Haisynska, who was Ukrainian. She worked as a judge and lawyer. They also tried to do everything possible to minimize my exposure to anti-Jewish manifestations.

Shimon Briman: Were there any encounters with antisemitism in your life, from childhood to adulthood?

Yuri Haisynsky: Of course, there were encounters with antisemitism. My grandfather Lazar taught me to strike back, i.e., respond to insults or the use of force. I did so in childhood, in adolescence, and in adulthood. I always strike back.

Shimon Briman: Were there also the opposite examples in your experience when Ukrainian colleagues and managers, knowing about your background, did not hinder, or even helped, you in life?

Yuri Haisynsky: Yes, there were many examples when Ukrainians showed friendliness and sympathy towards me, knowing about my Jewish background. Examples include Ivan Tsesarenko, the Kharkiv region prosecutor from 1968 to 1986; Mykola Marynenko, First Secretary of the CPSU Krasnohrad District Committee of the Kharkiv region, and Prosecutor General Mykhailo Potebenko.

I will share one funny episode. In the 1970s, we went to Leningrad as part of a group of Krasnohrad residents led by Mykola Marynenko, who initiated my appointment as head of the prosecutor's office of the Krasnohrad district. In St. Isaac's Cathedral, the tour guide explained that one of the paintings was called Circumcision of Our Lord Jesus Christ. Marynenko turned to me: "Yura, did you know about the Jewish origin of Jesus?" I answered in the affirmative. Then, Marynenko told me: "Nationality will not prevent a talented person from becoming even God." I did not object...

Shimon Briman: You became an assistant prosecutor in the Krasnohrad district of the Kharkiv region at 22 and later a district prosecutor at a very young age. Were you a tough or a "kind" prosecutor? When did you realize that the entire socialist system was not viable?

Yuri Haisynsky: Regarding the prosecutor, the terms "tough/kind" have specific meanings. For example, when investigating crimes against a person (murder, rape, or battery), the prosecutor is, in many cases, obliged to show courage and be "kind" towards the victims, protecting their interests. Not all victims have the opportunity to have a good lawyer.

The rest depends on the personal qualities of the prosecutor and the level of his or her qualifications. My prosecutorial "basic training" gave me a foundation of knowledge that contributed to a successful career as a prosecutor and later as a politician.

Many educated people doubted the effectiveness of the socialist economy, as well as "socialist humanity" and "socialist legality." However, the majority remained silent. Few began to speak out. This was facilitated by the Khrushchev thaw and especially by Western radio broadcasts.

When I started working in the prosecutor's office of a rural district, my doubts began to be reinforced by the inefficiency of the collective farm and state farm economy. Then, in 1985, perestroika began.

Shimon Briman: In 1985, you became the Moskovsky district prosecutor in Kharkiv. This is a huge district with 300,000 people, where I also lived as a school student. What do you remember about those first years of perestroika?

Yuri Haisynsky: Perestroika allowed me to read many previously inaccessible publications. I met interesting people in Kharkiv, including historian Valeriy Meshcheriakov, associate professor at Kharkiv State University.

Shimon Briman: In 1988, you and Meshcheriakov became founders of the Memorial Society in Kharkiv. What led the prosecutor to uncover the crimes of the Stalin era? Did you feel that by revealing Stalin's repressions, you were "cutting the branch you were sitting on"?

Yuri Haisynsky: We would gather in the evenings at Kharkiv University, discussing practical steps towards creating a non-communist NGO. Then, the Memorial Society was established in 1988. In January 1989, Meshcheriakov, I, and several other Kharkiv residents elected as delegates to the Memorial's founding congress arrived in Moscow. Never before had I seen such a huge number of television journalists. We wanted freedom and did not want communism, so we decided to start by exposing Stalin's criminal practice of abuse of power.

Shimon Briman: Your appointment to the first prosecutor's position in the Kharkiv region was approved by the USSR Prosecutor General Rudenko. Classified materials about his participation in mass repressions in the Donbas in the late 1930s have now been published. He signed hundreds of execution sentences. Has your attitude towards him changed?

Yuri Haisynsky: I only saw Rudenko on TV. For me, he was the main state prosecutor representing the USSR at the Nuremberg Trials. I learned about his personal participation in Stalinist repressions during perestroika, as well as about the abuse of power by Judge Nikitchenko, who was one of the two judges representing the USSR on the Nuremberg Tribunal.

This information was not something new to me that would have changed my attitude towards Rudenko personally. It was clear that in October 1917, the power was seized by a criminal group of communist fanatics who tortured the country, destroying the most intelligent, hardworking, honest, and responsible people. Criminals were in power in the USSR until the 1950s. I am grateful to fate for allowing me to participate in real decommunization.

Shimon Briman: Hennadiy Kernes, a controversial political figure and the former mayor of Kharkiv, was your son-in-law, and you knew him for many years. What is your memory of him?

Yuri Haisynsky: I have the impression that Hennadiy Kernes loved Kharkiv and did a lot to improve the quality of life in the city. This was made possible largely due to the opportunities provided by the abolition of the communist system and the introduction of freedom of enterprise, achieved in Ukraine in 1990–91.

Shimon Briman: You were elected a Ukrainian MP in March 1990 to represent the Moskovsky (now Saltivsky) district in Kharkiv. What do you call the things the Russian invaders have been doing to Saltivka for the fourth year now? In your opinion, is there a legal assessment of missile strikes on peaceful buildings and residential areas?

Yuri Haisynsky: The bombing of Kharkiv with Russian missiles, bombs, and drones, as well as the shelling of any civilian objects in Ukraine, are war crimes.

Shimon Briman: Your grandfather Lazar read you a book in Yiddish about Nazi atrocities and told you that, in alliance with America and England, "we defeated the Nazis and after that there were the Nuremberg Trials, and those who shouted 'Beat the Jews!' were hanged." When the war with the Russian Federation ends, do we need to charge those responsible for the murders of civilians in Ukraine during Russia's aggression? What is your general attitude towards this war and the inability of global institutions to stop this aggression?

Yuri Haisynsky: Authoritative world leaders and world powers, including the USA, are trying to stop this war. So far, without success. A person who is not an expert in the military-political sphere cannot answer this question. But I must remind you of a legal maxim that I consider fair for all times and peoples: "Justice must be done, even if the world perishes."

Shimon Briman: You financed the construction of a monument to the victims of the pogrom in Hermanivka, Kyiv region. Why precisely in that village?

Yuri Haisynsky: Anatoliy Shafarenko, a native of this village in the Kyiv region, had the idea to erect a monument to the Jewish pogrom victims. He told me that many Jews lived in Hermanivka before the revolution, but there are none left now.

Back in Soviet times, his father was ordered to remove tombstones from the Jewish cemeteries in Hermanivka. One large monument could not be moved. So, they dug a huge hole in front of it, tied it with ropes to a horse-drawn cart, and yanked it so that it fell into the hole. The tombstone was buried in the ground; both Jewish cemeteries were destroyed.

I knew about the so-called "reconstruction" (read destruction) of Jewish cemeteries in Soviet times. Still, the story of the buried tombstone moved me, and I offered to finance the construction of a monument to the victims of Jewish pogroms in Hermanivka. The monument was installed in the presence of two rabbis and villagers. I also spoke at this mournful rally.

Shimon Briman: How do you generally feel about the problems of historical memory in Ukraine and the memorialization of the Holocaust?

Yuri Haisynsky: If there is a problem in people's historical memory, it can remain a problem for many years. Memorials to Holocaust victims began to be built in Ukraine after independence.

On 5 October 1991, Leonid Kravchuk, Chairman of Ukraine's Verkhovna Rada at the time, gave a speech at a memorial ceremony to mark the 50th anniversary of the Babyn Yar tragedy. He found the words worthy of a world-class statesman. Two months after that speech, he was elected President of Ukraine.

I am very saddened that a memorial complex has not yet been built in Babyn Yar. I was in the USA in 2006, and they have Holocaust memorial complexes. There is a museum in Washington, a monument in Miami, and they do not leave normal people indifferent. But there was no Holocaust in the USA...

Shimon Briman: You started your career at a time when you could be fired or imprisoned for having connections with or sympathies for Israel. Do you remember your reaction to the news about the Six-Day War of 1967 and the Yom Kippur War of 1973? How has your attitude towards Israel changed over the past decades? In your opinion, would it be useful for Ukraine to learn from the Israeli experience?

Yuri Haisynsky: During the Six-Day War of 1967, I was happy with Israel's victory. I told my father about my desire to go to Israel. I was under 20 and could serve in the army. My father reminded me that I did not speak Hebrew, had not yet served in the Soviet army, or graduated from college. So, I stayed in the USSR.

I followed the reports of Western radio stations about the 1973 Yom Kippur War and, of course, felt spiritual comfort.

My attitude towards Israel has remained unchanged. I was not the only one who sympathized with the Jewish state. There were many sympathizers among my non-Jewish friends and acquaintances.

Over the past decades, Israel has given more and more reasons to be proud of the talented and hardworking Israelis who have transformed malarial swamps and deserts into blooming gardens, ensuring a high quality of life.

Israel's indicators in the latest technologies, free enterprise, medicine, education and, of course, defense and security are impressive. Ukraine and Israel have many opportunities for cooperation.

Shimon Briman: The United States have the "founding fathers," namely Franklin, Washington, Adams, Jefferson, and others. Do you feel you are like that for Ukraine?

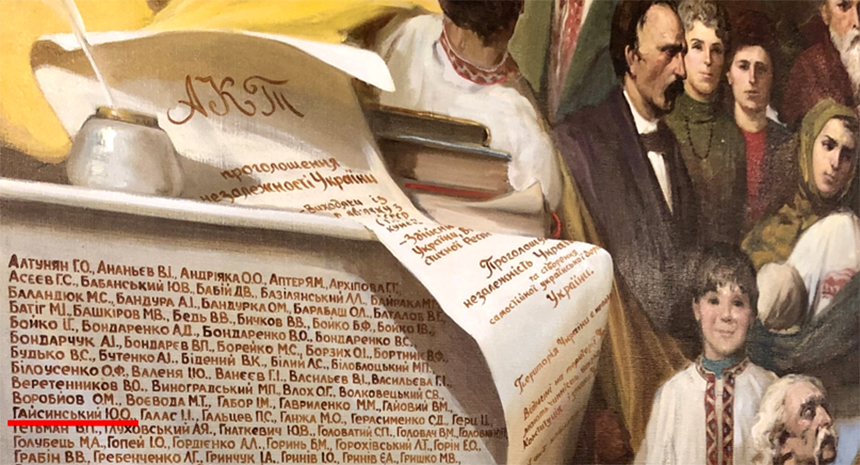

Yuri Haisynsky: Yes, I feel like one of the "founding fathers" of an independent Ukraine. My name is inscribed in the annals of its history, literally. State Formation, a huge panel painting by Oleksiy Kulakov exhibited in the Verkhovna Rada building, features the names and initials of Ukrainian MPs who voted for the Act of Proclamation of Independence of Ukraine on 24 August 1991. My name is also there, which fills me with pride.

Text: Shimon Briman (Israel).

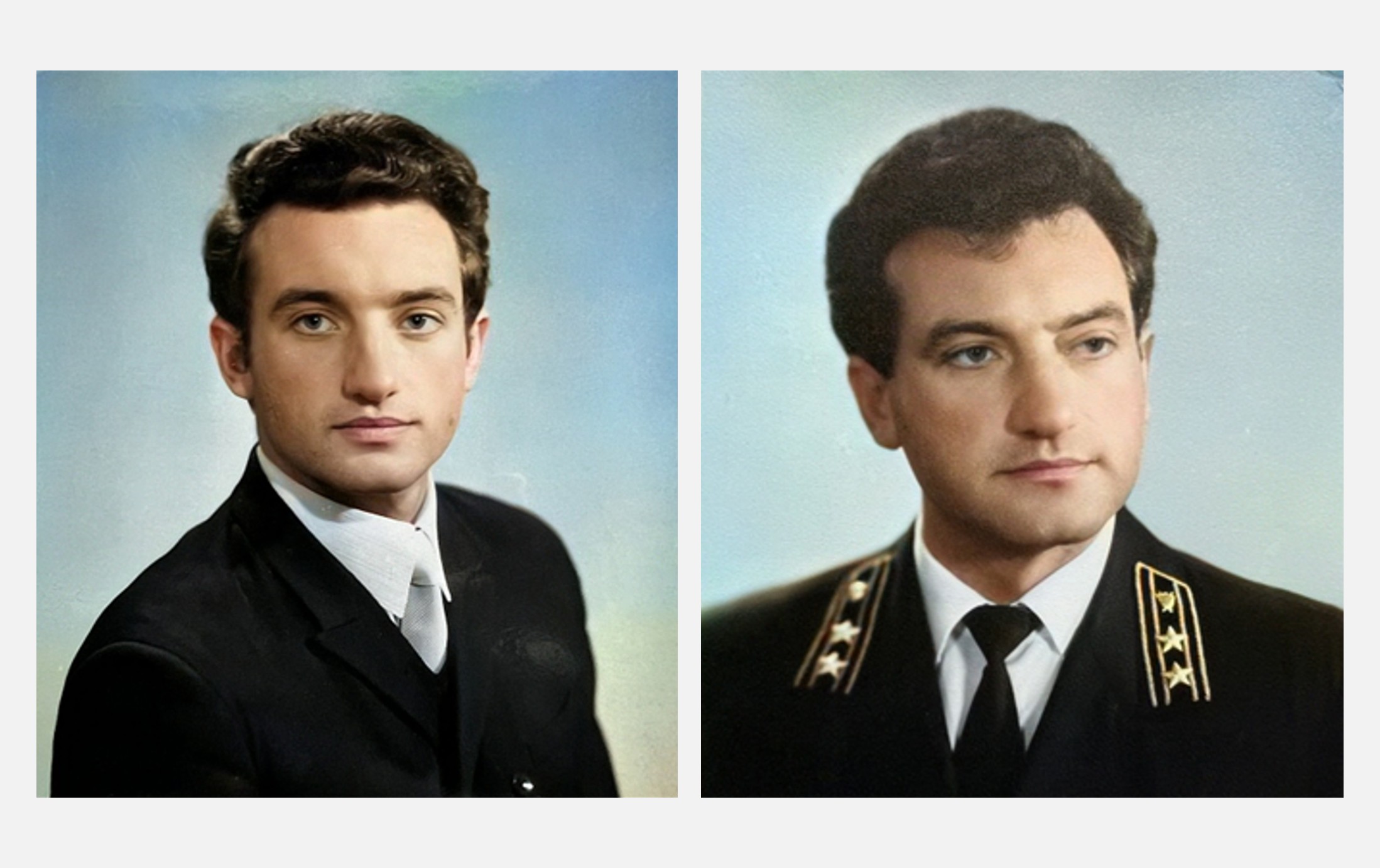

Photos: Yuri Haisynsky's personal archive.

Translated from the Ukrainian by Vasyl Starko.