A mirror, paintings, and horses: What do the heroes of Jewish tales recount in interwar Chernivtsi?

The Yiddish literature specialist Moshe Lemster talks about the Bessarabian fabulist Eliezer Shteynbarg.

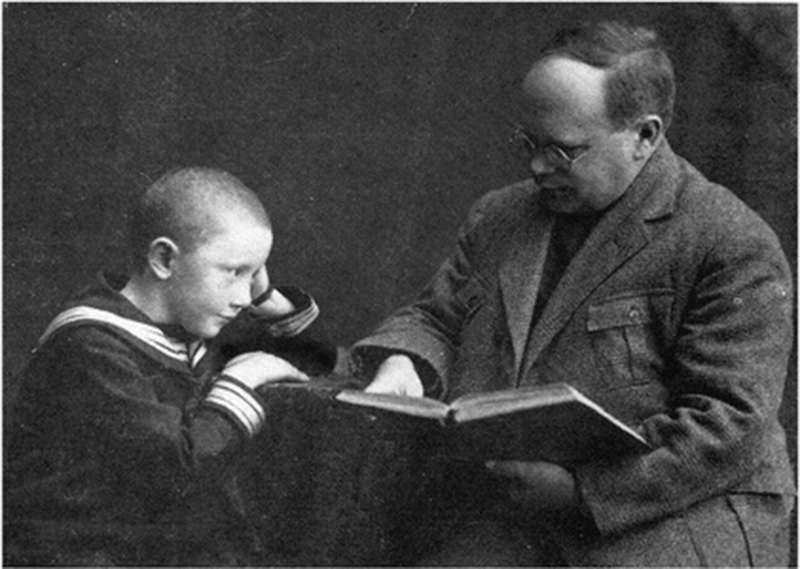

Andriy Kobalia: In the late nineteenth century, in a frontier village in Khotyn County, Bessarabia gubernia, fables began to be written by a person who would later become a classic of Jewish literature. Today his works are translated into Romanian, Hebrew, Portuguese, German, English, and Russian. However, in his native lands of Ukraine and Moldova, he is little known to this day. In 1919 Eliezer Shteynbarg moved to Chernivtsi, a city that had just become part of the Kingdom of Romania. Professor Moshe Lemster of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, who has been studying Shteynbarg’s works for two decades, explains what the Yiddish-speaking fabulist wrote about in his tales.

Moshe Lemster: He is quite well known in Yiddish literature. In my opinion, Eliezer Shteynbarg should be no less popular than Sholem Aleichem. He wrote in the genre of fables. When fables are mentioned, one immediately thinks of [Ivan] Krylov, Jean de Lafontaine, or Aesop. These are three classic authors of fables; their texts may be called the arithmetic of the genre. Shteynbarg’s fables are higher mathematics. Unfortunately, he was rarely translated. In Jewish schools few people were aware of him. His works were not translated into Russian either.

For my book I made a large selection of his fables. Sholem Aleichem is known for his plays. But besides him, there were many other writers. In Bukovyna there was Itsik Manger; he may be called a European-class poet.

Shteynbarg was born in 1880 in the small Bessarabian town of Lipkany, which is in Moldova. At the time this was the Russian Empire. In 1918 Lipkany and Chernivtsi, Bukovyna and Bessarabia became Romanian. The next year he moved to Chernivtsi. He did not publish a single large work before 1939.

Andriy Kobalia: What was he doing all this time?

Moshe Lemster: He wrote fables and published some things in Odesa. He had an illustrated book called 12 Fables; it is very beautiful, but only a few copies were issued. He also published an ABC book in Greek and Yiddish. He was very much loved in Chernivtsi, and he liked this city. In 1928 Europe learned about Bukovyna’s Jewish literature and about Shteynbarg. That year marked the twentieth anniversary of the Chernivtsi conference on the Yiddish language. Writers from around the world arrived in the city, and they met him. At the time many people said that his fables were high-level, classic works.

I have said that his fables are higher mathematics. Why? How do they differ from those that I mentioned? By the fact that his fables lack a moral. Readers themselves are supposed to do this on the basis of what they have read. Shteynbarg has more classical works that have a clear-cut moral and message.

Andriy Kobalia: Can one call this an evolution? In other words, he wrote fables with a clear-cut moral and then switched to another format?

Moshe Lemster: Not quite. He was a philosopher and a poet, who wrote mostly stories and poems for children. Near Chernivtsi is the village of Vyzhenka (today: Chernivtsi oblast—Ed.), where he was the director of a children’s camp. At the time this was a vacation spot for children of influential lawyers, judges, and prosecutors. In other words, he was involved in many things.

The structure of his fables includes lyrical elements, plot development, and some final conclusions. The philosophical fables may be called fables because the main heroes are not people but various objects or, for example, a rainbow.

Andriy Kobalia: Are there Bessarabian and Chernivtsi motifs in his fables?

Moshe Lemster: The fact that he is a Bessarabian writer is understood from the language, because in these lands Yiddish differs from Chernivtsi Yiddish. Yiddish specialists feel this rhythm and the very style. Incidentally, he became famous thanks to the reader Grozbard, who travelled the world reading his fables. What are they like? He wrote social fables that appealed to the younger generation. There was much in them about the difficult economic conditions.

Andriy Kobalia: Shteynbarg was alive during the interwar period, when Romania ruled over these lands. Did he have problems with the authorities? After all, at a certain point Bucharest became quite totalitarian.

Moshe Lemster: Most of his problems were connected with the Jewish authorities; there were no issues with the Romanians. Chernivtsi was home to Zionists, Bundists, and communists. There were constant conflicts among them. Unlike them, he was always above this. That is why people respected Shteynbarg, a person who was well versed in ancient languages, and ancient Hebrew. The Zionists, the Bundists, and the communists considered him an authority; he was like a bridge linking Jewish life in this city. For example, the ABC book in ancient Hebrew was financed by the Zionists. The Yiddish primer was financed by the communists.

In 1928 he went to Brazil, where he became a school principal. But even there he had problems with the Jewish Section. He fled back to Chernivtsi, where he lived until his death. In those years Shteynbarg traveled frequently in Romania. Thanks to him, Chernivtsi became the cultural center of Yiddish in the state.

Andriy Kobalia: Conflicts. You mean threats?

Moshe Lemster: No, it was more interpersonal strife. Small-town mentality, lease-holder mentality. Other Jewish writers often visited him to get advice, and he became an editor of local Yiddish-language publications.

Andriy Kobalia: Before the interview, you said that he didn’t know how to voice his own texts.

Moshe Lemster: Yes, he didn’t know how to read as an actor. He often stumbled. It often happens that poets do not know how to voice their own texts.

Why did Chernivtsi become the cultural center of the Yiddish language? By the 1920s the German language had become less popular, and Romanian had not managed yet to gain a dominant position. This vacuum was filled by Yiddish culture. Yes, cities do not figure in his texts, but he mentions social conflicts. For example, the fables feature “Shirts” or “Frogs” that argue about how to create a parliament and clean up the mud. But things remained as they were. In other words, he demonstrates his attitude to social processes through fables.

Shteynbarg died in 1932, following a failed appendectomy. He got sepsis. One can say that he wrote and published his texts at a very slow pace. The first fable was published in a newspaper in 1910, and his first book came out after his death. He was editing it in his final months, but most of the work was done by his friends.

Andriy Kobalia: How can this be explained?

Moshe Lemster: He wasn’t in any hurry. He wanted to publish a fine book. We saw an exhibit at the 2018 Yiddish Language International Commemorative Conference, which featured illustrations to the book. A large part of the work was done by his friends. Thanks to them, the first volume was issued in 1932, after his death. Later, they began to be published at a faster pace. In recent years translations into Hebrew have been published in Israel, as well as an anthology of children’s stories. He is known there more or less.

Andriy Kobalia: If he wasn’t in any hurry, how did he earn a living?

Moshe Lemster: For some time, he taught in small towns. In Chernivtsi he became the head of the Federation of Jewish School Organizations. I think that for the most part he worked in civic positions and received assistance from his friends. The book was published through sponsor funding.

I want to read “The Horse and the Knout,” a social fable with a moral. It was also read by Grozbard.

“A mare says to a knout: ‘Damn you. You and the driver, can I endure you any longer? For a trifle, you fight so much, as though I am an ordinary donkey. You think it’s easy to drag a cart behind you over the snow? If you would just save a bit of barley for me. Or a tiny bit of oats. You see, I have it worse than a dog, the life of a patient nag.’ The knout’s reply was heated. He flicked his biting tongue, ‘You’re wrong in what you say. I know that the wagon is heavy. I understand there is no question of running when there is no feed in the feedbag. But I will tell you a secret: I beat you in fact not because you’re barely plodding. God be with you. I beat because you have become a slave. That’s the point. And I will scourge you for having allowed yourself to be harnessed.’”

Andriy Kobalia: How can this fable be interpreted?

Moshe Lemster: You shouldn’t allow yourself to be harnessed. You get yourself harnessed then you complain that you are beaten with a knout. But if that had not happened, you would not be beaten. Shteynbarg wrote this text at a time when many people in these lands had begun working in cities as though they had been put in a harness. This fable is about the artist’s relationship with the surrounding reality.

He also has a fable entitled “The Mirror and the Painting.” The former says: “I reflect everything.” The painting says to it: “You reflect everyone who is in front of you—everything, precisely because you are no one.” Shteynbarg believes that art should not reflect but offer a vision, a dream. He has a fable called “About an Angel and a Mirror.” It’s the same story, but the angel says: “It is easy to reflect. Show a dream, why don’t you. You show the face of a child that is sleeping. But what kind of dream is it dreaming?” The artist has to show a dream. In his view, an artist has to convey everything through fables.

Andriy Kobalia: Did Shteynbarg write differently in the last years of his life?

Moshe Lemster: The texts became more philosophical and less social. He writes that in life there is dirt, but what will you say when the sun rises? In those moments happiness instantly appears. These are not even fables but philosophical poems. The objects and animals that are the participants in the fables are all Jewish. They have Jewish public education and folklore. By their subjects, they are reminiscent of proverbs and sayings that Shteynbarg himself invented.

This program was made possible by the Canadian non-profit organization Ukrainian Jewish Encounter.

Originally appeared in Ukrainian (Hromadske Radio podcast) here.

Translated from the Ukrainian and the Russian by Marta D. Olynyk.

Edited by Peter Bejger.

NOTE: UJE does not necessarily endorse opinions expressed in articles and other materials published on its website and social media pages. Such materials are posted to promote discussion related to Ukrainian-Jewish interactions and relations. The website and social media pages will be places of information that reflect varied viewpoints.