"A strong person does not blame their problem on some ethnic group." The story of the Rapoport family

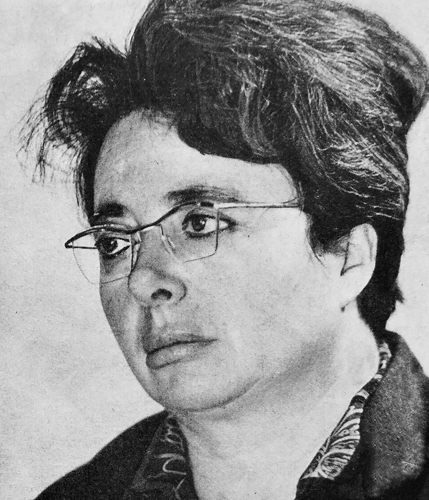

This Hromadske Radio broadcast is about Olena Ahamian, Liubov Rapoport, their development as painters, and their Jewish context. The guest in the studio is painter Olena Ahamian, Liubov Rapoport's sister.

How Liubov Rapoport's and Olena Ahamian's art was influenced by their parents

Elyzaveta Tsarehradska: I hunt for the Zeitgeist in my conversations. It's fascinating when you reconstruct it in stories. You and Liubov Rapoport are painters and the children of artists. Please tell us about your childhood, growth, and professional development. Were there any special moments? Did you put extra effort into it or just watch your parents at work? How did it happen?

Olena Ahamyan: My grandchildren recently asked me what our father forbade us to do. My sister and I could not remember a thing; he did not forbid us anything. I did not wash my brushes once, and my father said I wouldn't be a painter. After that, I made sure to clean my brushes. So, it doesn't mean we could do anything we wanted.

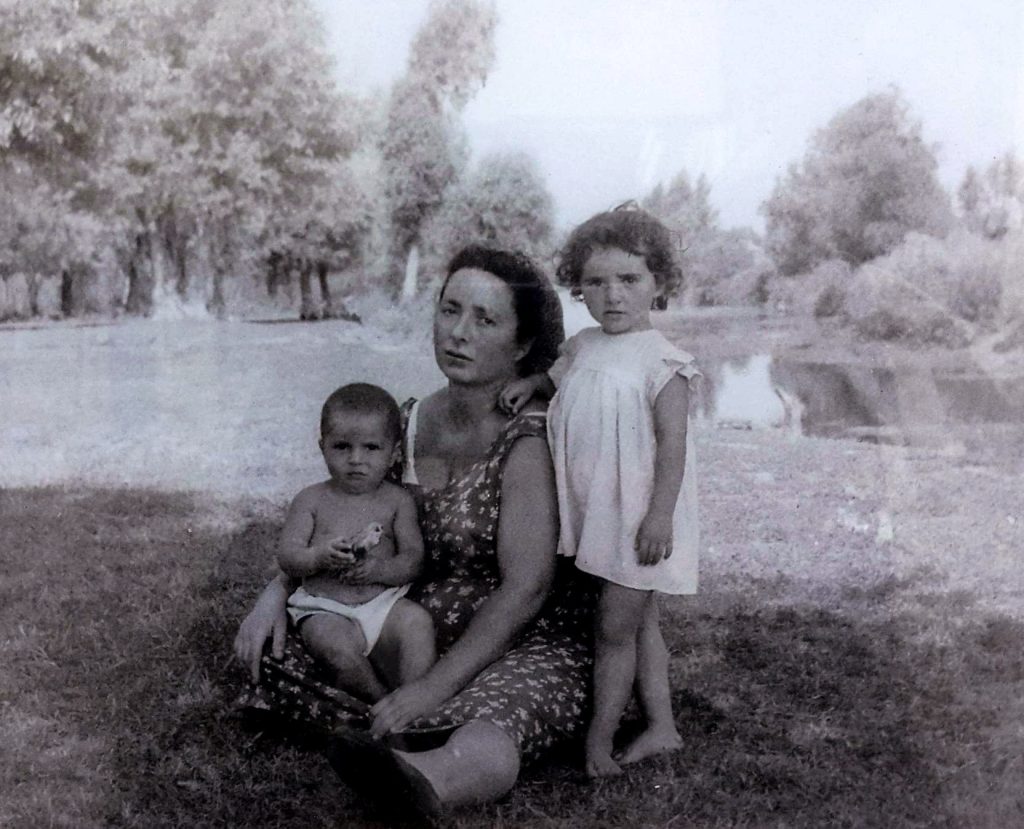

We had a creative working atmosphere and understood that our parents were doing their work. We were fortunate to have extraordinary individuals as our parents, both mom and dad. They were not at all similar as individuals and artists.

When my mother passed away, I had a dream of mounting a family exhibition. Everyone knows Liubov, but I wanted to show clearly where it all came from. At the exhibition, I was asked why the works were so different from each other. Indeed, when there is a family of artists, you can tell that their works are similar. However, our parents did not try to pass on a certain manner of painting to us. Instead, they just wanted to help us feel what we had from God. The precise words "from God" were never said, but every person is born with some gift. So, we absorbed a lot from our parents.

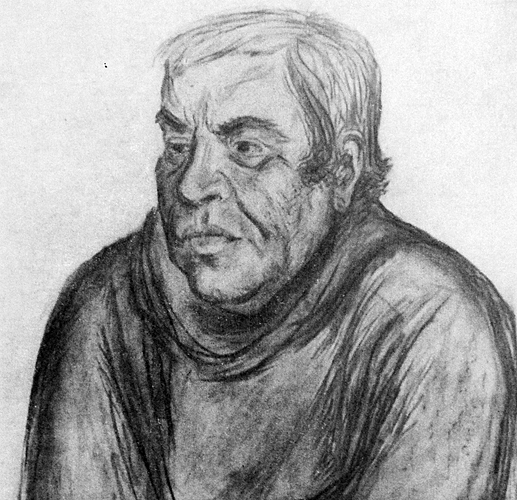

Our father, Borys Rapoport, always talked about his teachers, and I later wrote pieces about them, which were published in the Vitchyzna (Motherland) magazine. First, I wrote about Fomin. A student of both Pavel Chistyakov and Ilya Repin, he taught at an art school and an art college. He didn't care about anything except painting and was very strict with his students. He was especially hard on those who, he saw, were gifted. He said that there was no need to steal. That is, if you liked someone's technique, topics, etc., you only had to do that which touched you. It was very memorable. That's the reason why we are not alike in our family.

Our parents bought many books. There were always good books at home: Miró, Matisse, books about Fauvism, etc. This was in the 1950s and 1960s, during the countrywide struggle against formalism. My mother's works were removed from exhibitions because she liked to circle her virtuoso works with a black outline. Liubov had an excellent teacher at the art school, Maya Serhiivna, a daughter of Serhii Hryhoriev. She was a favorite teacher, and she taught them a lot. She loved children but was taken away from school for breeding formalism, as they put it. Many highly talented artists, such as Oksana Lysenko and Serhii Yakutovych, were among her students.

Elyzaveta Tsarehradska: Our listeners can search online to see the works of your father, Borys Rapoport, and your mother, Hanna Fainerman. This program aims to help a broad audience learn more about our artists and their art.

Growing up in Kyiv's artistic milieu

Elyzaveta Tsarehradska: You grew up in Kyiv, in the 1950s. Do you remember any prohibitions? I mean not in your family but in general. Do you remember this period as a time of restrictions and prohibitions? Did you hear about them from your parents? What did they talk about with their guests from the artistic milieu?

Olena Ahamian: My parents were free people. And I did not feel unfreedom or constraintsbecause our place was visited by people whom my parents liked. We had a very open and warm home.

My sister and I first lived on Gogolivska Street. It was the apartment of my grandmother's colleague. She simply let her mother and grandmother in after the evacuation. It was an 11-square-meter room, and we all lived there.

It was a very warm place. When my father came from artistic trips, I remember he would put sketches somewhere near the sideboard, and everyone would gather there to examine them. I don't understand how it happened because we only had eleven square meters. It was very cozy. We lived there; our grandmother lived there, and then there was always someone else. It's a case when the housing issue did not corrupt anyone.

We had no restrictions. I later learned that when Sosiura wrote "Love Ukraine" in the 1940s, all organizations began to seek out composers and artists with an inclination for the "kulak" sentiments of a "small, blooming" Ukraine.

I did not feel any constraints. I was born in 1951, and my sister was born a year later. It was so warm and so nice. The war was over, and you could paint, buy food, meet with friends, and travel everywhere. However, this was also when the "doctors' plot" case was on and when Jewish poets were shot. It was all there, but we, as children, did not experience it.

On Jewish ethnicity

Elyzaveta Tsarehradska: Was your Jewish identity articulated, or was it a carefully guarded secret? Was there any fear in your family because of your Jewish background?

Olena Ahamian: No one ever concealed from us that we were Jews. It was just this kind of generation: our parents' families did not follow religious rules. They were born in 1922, i.e., they were pioneers. Our parents understood a little more than we did because Dad's father was shot on allegations of spying for Romania when Dad was still a child. But there was no Jewish identity. I wanted to learn the language of the Jews, and I didn't even realize then that there were two languages, Hebrew and Yiddish. I had many wishes, but it was impossible to do everything.

There were years when we were supposed to be ashamed of their Jewish background, and people complied. It was very funny and still is. There is, so to speak, a significant lack of love for my people worldwide. I have learned from my family that you can't be ashamed and hide your ethnicity because you disown your parents, grandfathers, and family by doing so.

Since childhood, I learned the lesson that one had to feel sorry for those for whom the nation came first, who thought they were better because they were not Jewish, etc. If I fail to achieve something in my life, I can say I was not accepted or not permitted to do the work because of my Jewish background, but this is the path of a weak person.

My father was good friends with the famous Ukrainian artist Hlushchenko, who greatly valued him. When I was in art school, Dad told me that Hlushchenko had shown him Hitler's watercolors. Surprised, Dad said that those were lousy works. It made an impression on me as a child. If that terrible person had known how to do watercolors, world history would have taken a different course.

Before Hitler became the Führer, he sat in a men's dormitory in Vienna and likely busied himself with copying architectural motifs from postcards. He was not admitted to any academy. At the same time, there were numerous wonderful artists there, including many Jews, who changed the world of art. And if you feel you are weak in something, you want to assert yourself. You can say that something is not working out for you because "they are all stingy; they are all helping each other; they are like that..." But a strong person does not blame their problems on some ethnic group.

Influences on Liubov Rapoport and Olena Ahamian

Elyzaveta Tsarehradska: Reading about Liubov Rapoport and how her art, style, and career are characterized, I learned that she drew inspiration from German expressionists at one point in time. What influenced her art and yours? Is there an element of identity, particularly your Jewish background, in it? And do you think it's worthwhile to frame the question like that?

Olena Ahamian: I don't think it's worthwhile. We had many books and went to museums. All of Kyiv's museums were ours. I remember that when I was at school, we went to see the funds of the Ukrainian museum [now the National Art Museum of Ukraine. — Ed.]. There, Dmytro Horbachov showed us artworks that could not be exhibited: Palmov, Petrytsky, and all the Boichukists [followers of Mykhailo Boichuk. — Trans.]. This also made an impression on us.

Liubov has been very fond of expressionists and naïve art. Once, I got an amateur naïve painting and had to give it to her as a gift because she liked it so much. Of course, Maria Prymachenko, Yelyzaveta Myronova (Liubov had her portrait), and Kateryna Bilokur influenced her work.

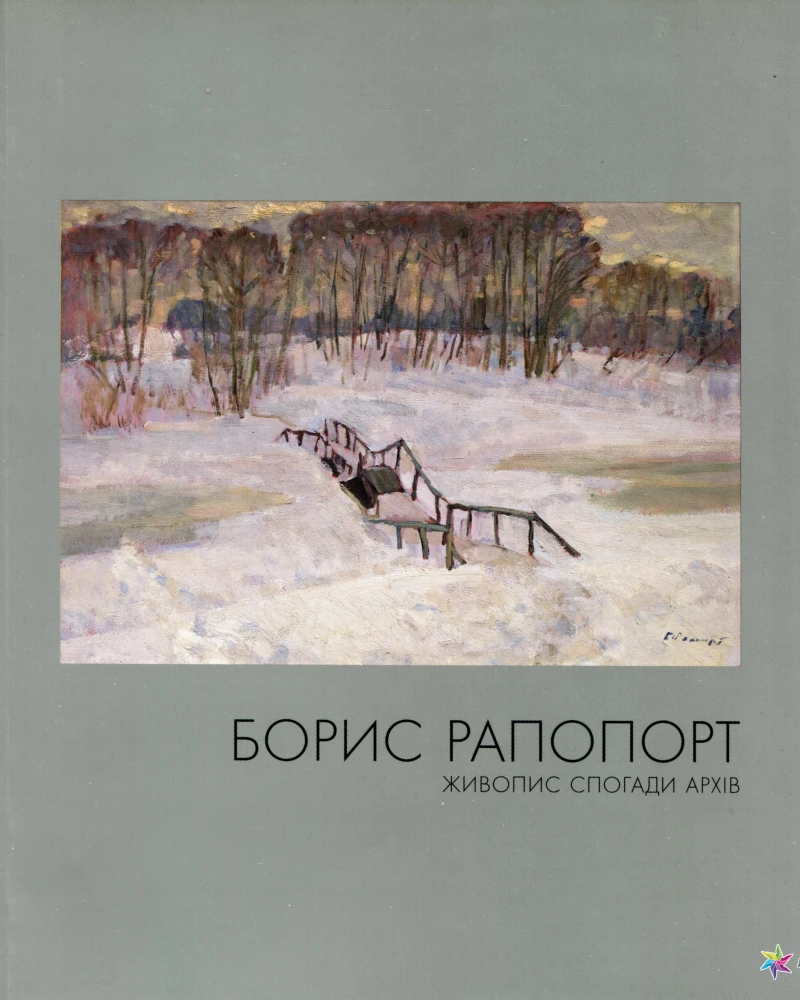

I would like to refer anyone interested in our family to the Art Rapoport Fainerman Facebook group. Started by my youngest daughter, this group features many works and documents. We also published two books some time ago. One, entitled Painting. Text. Drawing, was about Liubov Rapoport and contained, among other things, her prose works and graphics. The other one, entitled Painting. Memoirs. Archive, was about our father, Borys Rapoport, and appeared on the list of Ukraine's top 20 books.

Where to find the works of Rapoport and Ahamian

Elyzaveta Tsarehradska: Where can Liubov Rapoport’s works be seen? Are you planning a large family exhibition?

Olena Ahamian: I dream of mounting this kind of exhibition. My and Liubov's works are in the National Art Museum of Ukraine and the Museum of Modern Art of Ukraine, which also keeps our parents' art. The works held in the museums have been evacuated and stored elsewhere. So, let's do everything we can to end this terrible war.

I have a dream, of course, to mount this kind of exhibition. I did many family exhibitions and received a lot of feedback from people saying that these events were precisely what they needed and had been looking forward to.

There were even some touching moments. I met an older woman in a hospital. Aware that I was an artist, she started telling a story about what I realized was my father's exhibition in 1960. This is what makes working, painting, and exhibitions worthwhile.

The Museum of Modern Art, which also has our works, hosted our exhibition some time ago. Around that time, I received a phone call from a schoolmate, an experienced art connoisseur who had been in other countries for a long while. He came to Kyiv and said he had not seen anything like that exhibition. Even the works of our parents, who are no longer active, look different and are not perceived the same way over time.

This program is created with the support of Ukrainian Jewish Encounter (UJE), a Canadian charitable non-profit organization.

Originally appeared in Ukrainian (Hromadske Radio podcast) here.

This transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

Translated from the Ukrainian by Vasyl Starko.

NOTE: UJE does not necessarily endorse opinions expressed in articles and other materials published on its website and social media pages. Such materials are posted to promote discussion related to Ukrainian-Jewish interactions and relations. The website and social media pages will be places of information that reflect varied viewpoints.