After the Ghettos of Czernowitz and Bershad — to a New Life in Israel

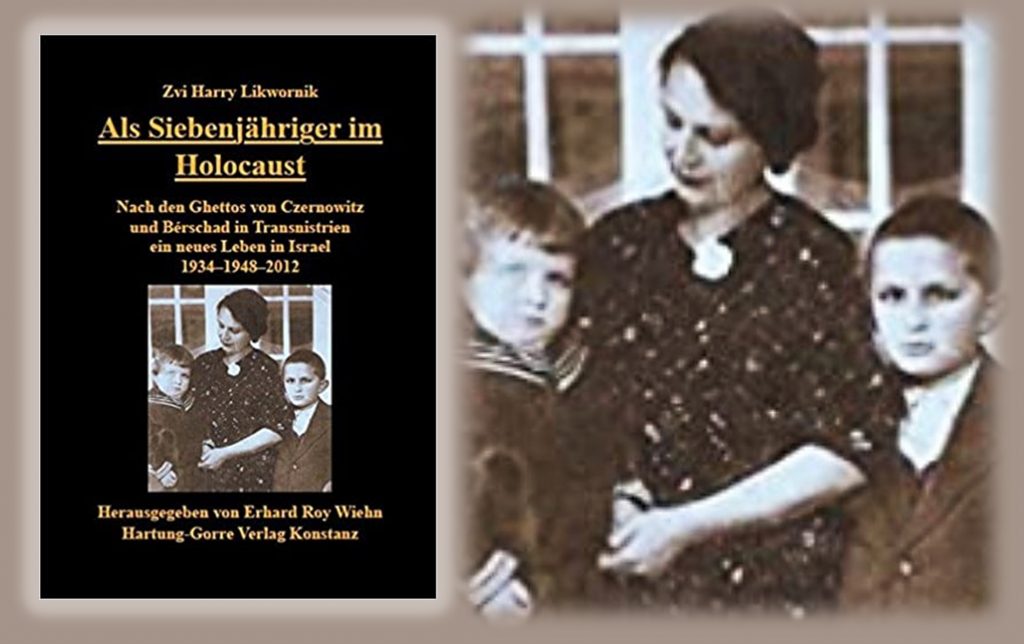

Book Review of Zvi Harry Likwornik, Als Siebenjähriger im Holocaust: Nach den Ghettos von Czernowitz und Bérschad in Transnistrien ein neues Leben in Israel 1934-1948-2012 (As a Seven-year-old in the Holocaust: After the Ghettos of Czernowitz and Bershad in Transnistria, a New Life in Israel 1934-1948-2012), trans. by Galia Ben Tov, ed. by Erhard Roy Wiehn (Constance: Hartung-Gorre Verlag, 2012).

Zvi Harry Likwornik’s memoirs first appeared in 2011 in Israel as a limited edition in Hebrew for friends and family. The discussed German-language publication of 2012 was translated from Hebrew to German by Galia Ben Tov. The 210-page book appeared in the publication series Shoáh and Judaica/Jewish Studies edited by Erhard Roy Wiehn, Professor Emeritus of history and sociology of the University of Constance.

The editor provided Likwornik’s autobiographical text with an extensive number of footnotes that offer short explanations of terms used by the author, or more regularly, pointing to further reading concerning the locations and the historical events referred to by the author. The editor also added a seven-page summary at the end, in which he concisely links Likwornik’s experiences with the course of historical events that caused Likwornik’s suffering.

At the end of the book is a four-page bibliography listing items of research pertaining to Jewish life and suffering in Romania, the Ukraine, Siberia and Transnistria.

Likwornik’s memoirs do not just make the Shoah in Transnistria and Bukovina come alive through his memories, but the book is also a very helpful resource for anyone interested in the Jewish history of that region.

Likwornik’s book, which he dedicated to his beloved mother, is a fascinating account of his life. The autobiography begins with his childhood memories in the Romanian and subsequently Soviet city of Czernowitz. The account then turns to his and his family’s experience of the Holocaust — of displacement, dispossession, humiliation, deprivation, hunger, death marches, ghetto life, and death.

Likwornik’s loss of childhood, which he suffered his whole life, began at the age of seven. Born in 1934 into a non-traditional Jewish family in Czernowitz, a Romanian city that was still characterised by the German language and the Austro-Hungarian cultural heritage, Likwornik and his older brother Manfred Elimelech experienced a happy and protected early childhood. Relations within the immediate family were mainly good, even though Likwornik occasionally shares disappointing memories of relations within the extended family.

In 1940 the picture began to change when the Soviet Union occupied Czernowitz and Northern Bukovina. Repressions, dispossessions, poverty, discrimination, and deportations set in; developments which the young Likwornik observed with interest.

The German-Romanian occupation, which followed the German invasion of the USSR, and the Romanian recapture of Northern Bukovina had a much more severe and destructive impact, however. Likwornik witnessed the ensuing violence and repression against the Jews, and in October 1941, the deportation of the city’s Jews, numbering more than 50,000, to the Czernowitz ghetto and shortly afterwards to the Romanian-occupied territory of Transnistria.

When the Czernowitz ghetto was dissolved, Likwornik and his family were among those who were deported and forced on a death march to the ghetto of Bershad, where life was characterised by great deprivation. Owing to the almost complete lack of heating material, food and medication, the number of sick and deaths increased. During the winter of 1941–42, at a time when his brother was very sick, Likwornik overheard his father trying to tell his wife Dora (and Likwornik’s mother), who herself was too sick to listen, that he had exhausted his strength; Likwornik subsequently saw him breaking down and dying right next to him.

With much ingenuity, the family managed to survive. The constant hunger was fought with cornflower, when available, eaten as mush or soup; a lice plague supplemented the trials. The family’s remaining three members survived two-and-a-half years in the ghetto of Bershad. Likwornik’s very present memories of the ghetto offer a vivid child’s view of life in the ghetto. His emotions, which range from shock and the incomprehensibility vis-à-vis events, from a sense of powerlessness and paralysis, and a deep sadness to unexpected joys over little unhoped-for acts of humanity, are described openly and with great courage.

When the ghetto was liberated by the Red Army in the spring of 1944, no one was there to help the former ghetto prisoners.

Likwornik’s autobiography further describes his family’s disappointing efforts to resettle in their former home city, now under Soviet rule. Not only had their flat been emptied, they had become strangers in Czernowitz, which was being more Sovietised, and they did not receive any assistance from anyone, apart from relatives, with whom they could stay.

Given that before the Soviet invasion (and before the subsequent Soviet re-conquest after the German-Romanian occupation), Czernowitz had belonged to Romania, the three Likworniks were permitted to “repatriate” to Romania and began a new life in Iaşi, where Likwornik could briefly attend school, for the first time in his life. Likwornik’s lack of schooling and education, of which he has been very self-conscious, was to become one of his great traumata, haunting him for the rest of his life. In Iaşi, Likwornik also experienced his “Aliyah LaTorah” (Bar Mitzvah) in circumstances that were less than worthy and adequate of the occasion.

Likwornik’s brother Manfred stayed temporarily in Brashov, where their uncle Isaac had offered him work. After returning to Iaşi, Manfred joined the Socialist Zionist youth organisation HaShomer HaTzair, and left for Palestine in November 1946 on board a ship that sank in a storm near Rhodes. Fishermen rescued the passengers, and they were able to continue their journey to Haifa on board the Knesset Israel. However, the ship was turned back by the British Navy, and the passengers were interned in Cyprus. After one year of internment, Manfred Elimelech arrived in Eretz Israel, where he was among the founders of Kibbutz Zikim south of Ashkelon.

Likwornik recounts how during this time, his family tried to return to a normal life and that he could not comprehend the Jewish community’s joy about the United Nations’ decision of November 1947 to end the British Mandate and to enable the creation of an Arab and a Jewish state. Likwornik and his mother had also joined Zionist organisations, HaShomer HaTzair and Al HaMishmar, respectively, and set out for Palestine in December 1947 on the Jewish Agency’s ship Pan York.

The memoirs go on to recount Likwornik’s experiences on the refugee ship, his time of internment by the British in Cyprus, including the enthusiastic reception by the internees of the news of the proclamation of the State of Israel. His account tells of his and his mother’s exciting arrival in Haifa, their early time in Israel in an immigrants’ camp in Pardes Hanna south of Haifa, and their first flat in Givat Aliyah in Jaffa, in a house which was empty since their former Arab residents had fled during the still ongoing War of Independence. On a personal level, above and beyond the external changes Likwornik experienced, he had to go through puberty in those years without having a father or anyone else with whom he would have felt comfortable to confide in. He was expected to work rather than continue his schooling. Likwornik writes about receiving his first wages, buying his first watch, helping his hard-working mother, who always selflessly helped others, run the household, meeting other relatives, and his first party at home, which his brother spoiled.

He also shares his memories of the development of the young Jewish State, the War of Independence, life in Jaffa and Tel Aviv, the economic crisis and the rationing of 1949-1952, and his military service a few years later.

At the end, Likwornik reflects on the lessons which he learned from life, about the great value of his father’s tefillin bag, which his aunt Rosa had kept and gave him as a gift in Israel in 1949. He reflects about memory, amnesia and recurring memory, including incessant nightmares, concerning his deeply traumatic experiences. He describes the functions of memory and forgetting in his life after the war and in his efforts to build a new life, marked by the unquenchable hope to live his dreams in the newly created State of Israel.

He writes about his work to make his experiences and knowledge of the Holocaust in general, and in Bukovina and Transnistria in particular, known by talking to interested groups, in Israeli institutions, and even in Germany, with the support of friends in Germany.

His autobiography ends with a report about two trips which he made to Bukovina and Czernowitz in 1998 and 2011 — trips which helped him to reconcile somewhat with his birthplace. His tone is very personal, filled with love, longing and compassion for his family, especially his heroic parents, whom he addresses directly in the book in two homages filled with words of enormous gratitude, respect, sadness, and the assurance that their lives and lines continue in his children and grandchildren.

Throughout the book, his words give emotional expression not only to his suffering as a child, but also to how these experiences and circumstances affected his entire being and deprived his whole life of normalcy. Nevertheless, he concludes with words of immense gratitude for having obtained the greatest gift, that of having his own family, a loving wife, children and grandchildren. The book also includes a section with photographs and documents pertaining to Likwornik’s biography, his family, and his later work to reach younger generations to commemorate the Shoah.

Author: Dr. Nicolas Dreyer,

Postdoctoral Researcher, Institute of Slavic Studies,

Otto Friedrich University Bamberg, Germany.