Anna Khromova: To this day, many people in Israel do not realize the Ukrainian language exists

How long ago did Israel realize that Ukraine is not Russia? What do the People of the Book read? Is there a chance for Ukrainian literature in this Jewish country? Which Israeli authors will we be seeing in Ukrainian-language translations? These are some of the questions featured in our interview with the Israeli writer and translator Anna Khromova, who was a guest at (the 2018) International Arsenal Book Festival.

Anna, to what degree are the People of the Book a book-reading nation today?

I don’t think that the People of the Book read more than other countries. There are popular segments: children's literature, cookbooks, books on religious topics, applied literature on psychology, women’s success, business, etc. I think that with the pace of contemporary life, reading belles-lettres has become a luxury even for those who love to read—and not just in Israel.

It is interesting that the level of printing is inferior to the Ukrainian one. Most books in Israel are published in softcover on ordinary paper in order to minimize cost price. Only when you walk through the Book Arsenal in Kyiv, browsing among the thousands of richly published folios, can you appreciate how far we are from Ukrainian luxury.

On the other hand, modest printing makes books relatively accessible. A few years ago the Knesset even repealed a law mandating that bookstores had no right to sell new items at a discount for a period of eighteen months. When the law was ratified, demand fell, especially for children’s literature, and parliament decided that caring about readers was more important than the rights of writers and publishers.

One way or another, a few years ago the country ranked second in the world in terms of book production per capita.

Yes, that’s something to be proud of, as well as the traditional Hebrew Book Week, which was first held during the British Mandate era. Today it is time to talk, not about a Book Week, but about a Hebrew Book Month, when book fairs take place throughout the country, as well as public readings, meetings with writers, events ranging from those geared to schoolchildren held in libraries to free lectures in houses of culture. For the state, this is a top-priority question, and measures are not limited to big cities; even the provinces garner the attention of authors and publishers.

Moreover, I have been convinced on many occasions that Israelis without a higher education have a very vague idea about fiction. For example, the names Romeo and Juliet may not mean a thing to a student at the Technion, the Israel Institute of Technology. This is a side effect of specialization in higher education, which is partly justified but sometimes fraught with gaps in the sphere of humanities.

Is a writer in Israel more than a writer?

If you recall that in the first Knesset there were eighteen writers among the 120 deputies—perhaps, yes. Even today there is an array of names that are known to every Israeli, even if s/he is far from literature. Everyone knows who Amos Oz, David Grossman, Meir Shalev, and Etgar Keret are. They are opinion leaders; people listen to them... Some actively convey their sociopolitical views to the masses, others are focused on creativity, but the voices of leading writers are heard, their statements make the news in prime time. For example, David Grossman’s speech at the alternative Israeli-Palestinian ceremony on Memorial Day for Israel’s Fallen Soldiers was widely discussed in the press. Keret’s political columns spark discussions. It is true that in recent years he is being published more often abroad and less so in Israel—apparently precisely because of the nature and sharpness of the public’s reaction to his statements.

Is there a place for translated literature on the Israeli market, particularly children’s literature?

The share of translated literature is quite large, and I’m not just talking about new works by English-speaking authors. The Little People, Big Dreams series of books, which tells children about outstanding women, was translated pretty quickly into Hebrew. (In Ukraine, this series is entitled For Little Ones about Big Ones.) It is noteworthy that in Israel the translation was supplemented by local heroines, including Prime Minister Golda Meir, the artist Anna Ticho, the spy Sarah Aaronsohn, and others.

Of course, Soviet children’s classics have been translated as well. [Samuil] Marshak appeared in Hebrew back in the 1940s. Around that time, Natan Alterman translated [Korney] Chukovsky’s Barmalei and Doctor Aibolit. Elly Sod published an alternative translation of Aibolit in 2017. Some thirty years ago Fuzzy-Wuzzy Busy Fly was translated into Hebrew by the then ten-year-old Einat Yakir. The legendary Leah Goldberg wrote about an absent-minded fellow from the village of Azar based on [Marshak’s] The Absentminded Fellow.

Are you at least a bit familiar with Ukrainian literature in Israel?

I know that a few of Andrey Kurkov’s novels have come out in Hebrew.

There is a wonderful translator named Anton Paperny, a native of Kharkiv, who is doing a lot to ensure that Ukrainian poetry is heard in Israel. He translates into Hebrew both classics, like [Taras] Shevchenko, [Ivan] Franko, and Lesia Ukrainka, and contemporary writers, including Yuri Andrukhovych, Marianna Kyianovska, Yulia Musakovska, Halyna Kruk, and many others. Thanks to him, books by Pavlychko, Vasyl Makhno, and Kateryna Kalytko have been published in Israel.

How long ago did the average Israel begin to understand that Ukraine is not Russia?

After the annexation of the Crimea and the beginning of the war in the Donbas. The average Israeli now knows that there is such a country as Ukraine. And s/he understands that it is not just Uman. Although to this day many people do not suspect the existence of the Ukrainian language. On the whole, however, the realization appeared in 2014 that the Russian Federation and Ukraine are two big differences, and people began to ask the question, “Are you Russian?” more cautiously, out of fear of offending their interlocutor. Ten years ago this nuance did not exist.

How much did the Maidan stimulate interest in everything Ukrainian?

Israelis are focused on their domestic problems. You notice this right away when you turn on the evening news, where international topics are presented very sparingly. The people who are involved in creating information programs admit that events abroad and the specific features of other cultures do not interest Israelis very much.

At the same time, in recent years natives of Ukraine have stepped up their activities, and a group has been formed, called Israeli Friends of Ukraine, which holds the ETHNO-Khutir Ukrainian heritage festival in Tel Aviv. It is attended mostly by émigrés from Ukraine as well as native Israelis. Yes, this is a local event, but it cannot be otherwise because the government encourages returnees to become part of Israeli society and deliberately does nothing to encourage them to remain part of the culture of their native country.

That’s understandable, but much depends on the number of Israelis who identify themselves with one community or another. If all the 300,000 emigrants from Ukraine considered themselves as Ukrainian Jews, then ETHNO-Khutir would partly resemble Mimouna (a holiday celebrated by North African Jews), which cannot fail to be noticed on the international level.

That is so, but you have to consider that, in abandoning a country—Ukraine, in this case—a person in his/her consciousness preserves the period during which s/he left. The main wave of repatriation took place in the early 1990s; that’s why people associate themselves with a state that is very different from contemporary Ukraine.

The culture of returnees that arose in Israel is often called “Russian,” although it is a Soviet subculture in a slightly modernized form. It is also present on the national level. For example, just a few years ago New Year’s was made into a holiday by choice, and now in December, you can buy tree ornaments.

Parallel to this is the process of strengthening Ukrainian identification, especially after 2014, and mostly among young people. There is a Ukrainian cultural center in Bat Yam, there are Ukrainian-language poets of various generations: Ivan Potemkin, Valentyna Chaika, Miriam-Feyga Bunimovich, and Max Lesovoy.

Occasionally, Ukrainian writers visit us and hold creative meetings. In recent years Vasyl Makhno, Sofia Andrukhovych, Irena Karpa, and Kateryna Babkina have visited Israel. It would be good if this list were expanded.

How are people in Israel reacting to the recent events in Ukraine?

The presidential elections were covered widely, but the headlines in all the newspapers were screaming about the nationality of the new president, although his previous occupation elicited as much interest as his Jewish background.

Nevertheless, from an impartial perspective, the elections did not polarize even the returnee milieu, in contrast to Ukraine. In Israel, people followed the process with good-natured curiosity and admired the campaign itself, which will go down in all PR textbooks.

Let’s go back to literature. Have there been any new trends in recent years?

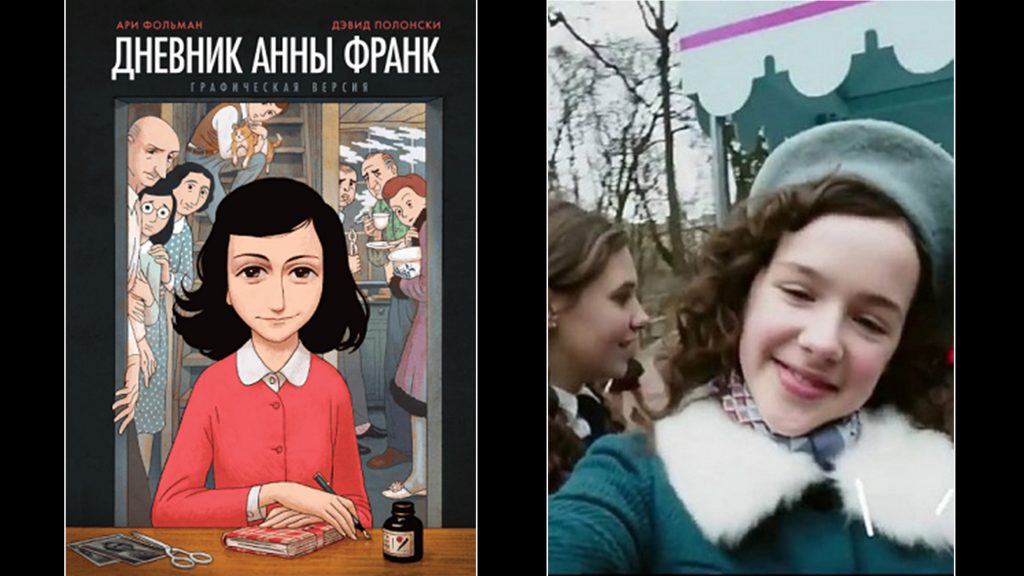

In children’s literature, there is a clear-cut demand for non-fiction. New expressive means are being mastered. For example, a striking comic book based on Anne Frank’s diary was released recently. Director and screenwriter Ari Folman and artist David Polonsky (incidentally, a native of Kyiv) worked on it. They may be familiar to the Ukrainian public because of the full-length animated film Waltz with Bashir. The fact is that showing yellowed old photographs and identifying who is depicted in them and what happened to him is one thing; it is quite another thing to reconstruct reality in ways that are familiar and understandable to a child.

Here I cannot avoid recalling the story of a thirteen-year-old Hungarian Jewish girl named Eva Heyman, who died in Auschwitz and whose fate was “revived” on Instagram. Her relatives were shaken because for the first time their children perceived the Holocaust theme as something close to them.

With our generation, it was probably easier. The traditional book completely satisfied curiosity. But means of communication have changed radically over the past twenty years, and they are the key to the hearts of modern children.

A few years ago your translation of Tirza Atar’s verse novel They Cry from the War was published in Lviv. Why was this particular book chosen?

I read Tirza’s book during Operation “Unbreakable Rock” in the summer of 2014, at the same time as the war in Ukraine began. All this was psychologically very difficult, and I could not even answer my children’s questions about how to deal with it. I turned to teachers and, since books are a great way of talking with children, I went to the library. That is when I first saw this book and later found out that it is part of the school curriculum. First of all, it is a very heartfelt story. Second, it is excellent literature; at the same time, it coincides with all the recommendations of psychologists about how to talk to a child about war. I began translating They Cry from the War after chatting with my girlfriends in Ukraine, who were encountering the same kinds of questions as I was. I sent the translation to the Lviv-based Old Lion Publishing House, realizing that the author’s name will not mean anything to the editors. But the publishers decided to do an experiment, and the book came out in Ukrainian with Kateryna Sadovshchuk’s beautiful illustrations.

Whom have you been translating recently?

Yona Wallach, Avot Yeshurun, Rokhl Korn. I would very much like to see a Ukrainian-language anthology of Yehuda Amichai’s writings, on which I have been working for a long time. On the whole, Israeli poetry is an amazing phenomenon, and I hope that the Ukrainian reader will be able to appreciate it.

From prose works, I would like to highlight the writer Bella Shaer, a native of Chernivtsi. Last year we launched the translation of one of her stories from the book Children’s Swear Words at the Island of Europe festival in Vinnytsia. It's subtle and poignant prose. It is interesting that the writer describes the Soviet way of life for Israelis, and this is done so subtly that it recreates a detailed picture of a bygone world, the atmosphere of a Chernivtsi house and its inhabitants. I am sure that the book would be interesting to Ukrainian readers; one publisher has already expressed interest in this novel. Cultural interaction is a two-way street, and our task is to intensify it.

Interviewed by Mikhail Gold

Originally appeared in Russian @Hadashot.

Translated from the Russian by Marta D. Olynyk.

Edited by Peter Bejger.

NOTE: UJE does not necessarily endorse opinions expressed in articles and other materials published on its website and social media pages. Such materials are posted to promote discussion related to Ukrainian-Jewish interactions and relations. The website and social media pages will be places of information that reflect varied viewpoints.