At the beginning of the 20th century, Boryslav was the world’s third-largest producer of oil after Pennsylvania and Baku — Vladyslava Moskalets

A conversation about “Galician California,” Bruno Schulz, oil, [Habsburg emperor] Franz Josef, and Jewish life in Western Ukraine.

Our guest on today’s program is Dr. Vladyslava Moskalets, Senior Lecturer in the Department of History at the Ukrainian Catholic University and coordinator of the Jewish Studies program.

Vasyl Shandro: What is “Galician California,” and where was it?

Vladyslava Moskalets: “Galician California,” as it was called at the beginning of the twentieth century, was the small town of Boryslav, known from Ivan Franko’s Boryslav Is Laughing, and which is linked to two other cities: Drohobych and the resort town of Truskavets. It is not far from Lviv. Oil was discovered in this region in the second half of the nineteenth century. There was oil there even earlier, a lot of it beneath the surface of the soil, but peasants did not really understand what could be done with it. It was only in the mid-century when a method for refining this oil was discovered and the gas lamp for lighting was invented, that this place begins to attract entrepreneurs. It develops over the next half-century, and by the beginning of the twentieth century, Boryslav is the world’s third-largest producer of oil after Pennsylvania and Baku [Azerbaijan—Trans.]. This place was very famous and much was written about it. It attracted numerous entrepreneurs and became very important in the economy of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Vasyl Shandro: What was the city of Boryslav like at the time?

Vladyslava Moskalets: Up until oil was discovered in Boryslav and began to be extracted, it was a village of little importance and of no interest to anybody. Within half a century, this village is transformed into a town that attracts mainly workers. Though the people who live there are usually workers, it’s difficult to call them a proletariat because some come to the town for seasonal work. They are peasants who come in temporarily to work in the oil fields or refineries. However, we have one population group that is present in the town the entire time — Jews. Jews did not return to summer fieldwork. They spend most of their time there.

At that time, Boryslav attracts very many Jewish entrepreneurs. If we look at who the owners of oil wells were in the 1860s and 1870s, they were mostly Jews. This begs the question: Why is this so, and why does this industry appeal so much to them? There are various answers to this, one of them being the fact that Jews quickly navigate new business opportunities and trends. When some Jews are engaged in a business, they bring in others along with them.

My research was about how formal and informal connections between business people and their families contributed to their becoming dominant in certain groups. This lasted roughly until the early part of the twentieth century, marking the arrival of Canadian and French companies, whose industry is on an entirely different level from these small, local entrepreneurs. The industry gradually becomes more professional, and the Jews are simply pushed out of it. By the beginning of the twentieth century, after the town had grown and become an industrial center, Jewish entrepreneurs no longer dominate this niche.

Vasyl Shandro: Could one encounter Jews among the workers?

Vladyslava Moskalets: Of course. The workers who stayed in Boryslav for the summer were Jews. There were quite a lot of Jews in the city, and the fact that there are workers there begins to attract the attention of their contemporaries because this was quite untypical. In Galicia, we have ethnic divisions that coincide with social ones: If you are a Ukrainian, you are probably a peasant; if you are a Pole, then you are a nobleman or from petty nobility; and if you are a Jew, then you either own a tavern, or you rent out rooms. Boryslav had somewhat of a more complicated social structure.

We have the so-called Boryslav war in 1884 involving big battles between Christian and Jewish workers, which bear a resemblance to parallel fights between two population groups. Since there are many Jewish workers, they feel quite confident. However, a crisis emerges at the end of the nineteenth century. Industry is modernizing, and there are fewer Jewish entrepreneurs. Accordingly, Jewish workers, who were often quite poorly qualified, became unemployed and had nowhere to go. They severed ties with the hometowns from which they had come.

This draws the attention of benefactors, who come to Boryslav and describe the horrors of that city. A socialist writer named Saul Raphael Landau, who visits in 1897, was up in arms about this. He attracts the interest of Theodor Herzl, one of the founders of Zionism, the national movement, and tries to organize the resettlement of these poor, unemployed Jewish workers and their families in Palestine. Some of them even immigrate there, but this move in no way reaches a mass scale during this period, and it couldn’t be a solution to this problem.

Vasyl Shandro: Did you use Ivan Franko’s work Boryslav smiietsia (Boryslav Is Laughing) in your research? Is it useful as a document?

Vladyslava Moskalets: Of course, it is important. When I was doing my research, I avoided the question of belles-lettres because there is a lot of fiction devoted to Boryslav, but it is very emotionally charged. It makes it very clear what views the authors are trying to disseminate. Franko wrote these works during a period when he was fascinated with socialism. He attempted to show through Marxism that Jews were the symbol of capitalists. Marx stated that for Jews to be emancipated from capitalism, they needed to emancipate themselves from themselves. A Jew is a capitalist; a capitalist is a Jew, which is quite ironic because Jews soon begin to be associated with socialism, not the bourgeoisie. Franko is quite ill-disposed toward the families of Jewish businesspeople. When you read Boryslav Is Laughing or any of his other works, you have to be prepared for this.

Vasyl Shandro: How did the press write about this at the time?

Vladyslava Moskalets: At that time in the nineteenth century, there were only a few local newspapers in Boryslav: the Polish-Ukrainian socialist newspaper Gazeta Naddniestrzańska and the Jewish newspaper Drohobyczer Zeitung. It was very interesting to compare how these newspapers viewed businesspeople and this entire milieu. The former constantly wrote about scandals and how these entrepreneurs were connected to each other. At the same time, every issue featured the following statement: “We hope that no one will consider us antisemites because we are only telling it like it is.”

An idea of a Jewish conspiracy in the city of Boryslav is formed, but when you read Jewish newspapers, you have somewhat different perspectives, a different idea about those businesspeople: They are building orphanages for children, homes for the elderly, they engage in philanthropy, and are generally involved in all kinds of charitable work. Non-Jewish newspapers demonize this greatly and show it in a very unfavorable light. All this would burgeon before elections; as soon as elections began, this black PR would start pouring from the local press.

Vasyl Shandro: How did the oil trade affect the surrounding cities, towns, and villages?

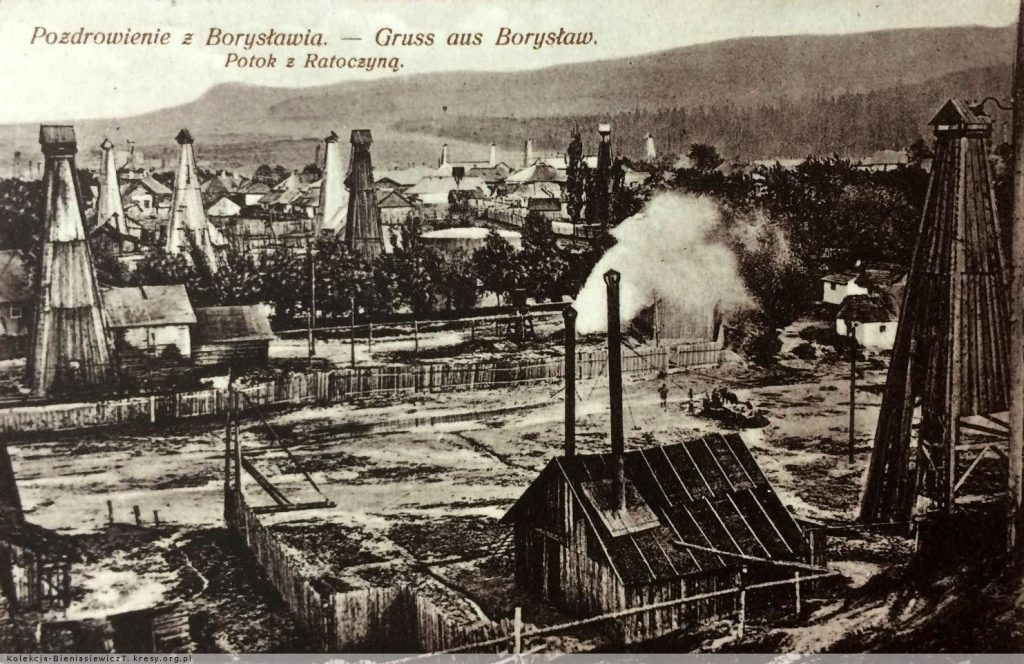

Vladyslava Moskalets: Drohobych was home to the administration, a gymnasium, and synagogues. Today one has been restored and can be visited, and another is not restored. Businesspeople invested their capital in it and lived there, some of them on Market Square. If we look at photographs of Boryslav, we see that before the end of the nineteenth century, this was not a city that was getting a lot of investments. There are wooden buildings; all around are mudflats. Boryslav resembles a kind of small hell. But Drohobych looks very respectable. Truskavets is a resort town that begins to develop quite late and becomes a real resort during the interwar period. These businesspeople come to Truskavets, too.

Eventually, at the beginning of the twentieth century, a few families that had acquired wealth move to Lviv — for example, the Segal family, which purchases the beautiful building one can see opposite the McDonald’s on Prospekt Shevchenka. Some go to Stanyslaviv [today Ivano-Frankivsk — Ed.], where they establish a spirits factory or construct a beautiful retail arcade of shops. They discover the Carpathians for themselves, and rows of villas for wealthy Jewish bourgeois families are built. The families of Jewish entrepreneurs go hunting, and their lifestyle is typical of the higher middle class. Their children often travel to Vienna and remain there, especially during the First World War when they flee the [Imperial Russian — Ed.] occupation. We can say that the wealth of these entrepreneurs is invested in these towns, and they also help to develop the architecture and infrastructure of other cities in the region.

Vasyl Shandro: What do Franz Josef and Bruno Schulz have to do with this?

Vladyslava Moskalets: Franz Josef is a symbol. The Jews of the Austro-Hungarian Empire are one of the most loyal population groups in the empire, constantly expressing their devotion to the ruling dynasty in their prayers and religious services. When Franz Josef came to Drohobych in 1870, he also visited one of the factories owned by Jewish entrepreneurs. One of these businessmen, Ascher Selig Lauterbach, was a highly intellectual figure who in his free time wrote philosophical treatises. In his memoirs, he proudly mentions the visit of Franz Josef to Drohobych and Boryslav.

Drohobych becomes a city where several important art figures are born. We have the Jewish painter Maurycy Gottlieb, who died very young and was a student of Jan Matejko and painted very interesting psychological works that united Jewish and Polish culture. We have the artist Ephraim Lilien, who produced engravings, including one of Theodor Herzl, the founder of Zionism. We also have Bruno Schulz, whose brother was in the oil business and used some of his funds to sponsor one of Bruno’s first books. It may be said that theoretically, in a certain sense, the oil business helps writers, pushes them to acquire an education, and get their first works published.

This program is created with the support of Ukrainian Jewish Encounter (UJE), a Canadian charitable non-profit organization.

Originally appeared in Ukrainian (Hromadske Radio podcast) here.

Translated from the Ukrainian by Marta D. Olynyk.

Edited by Peter Bejger.

NOTE: UJE does not necessarily endorse opinions expressed in articles and other materials published on its website and social media pages. Such materials are posted to promote discussion related to Ukrainian-Jewish interactions and relations. The website and social media pages will be places of information that reflect varied viewpoints.