Babyn Yar’s Brutal Multi-layered History Revealed in an Important New Study

Babyn Yar today is a tree-lined park on the outskirts of Kyiv that offers the city’s residents refuge from the scorching summer heat. Seventy-five years ago, this peaceful setting of parkland was the site of one of the most notorious crimes of the Holocaust.

In a two-day period in late September 1941, nearly 34,000 Kyiv Jews were shot to death amidst a bucolic landscape once called the “Switzerland of Kyiv.” Over the next two years, an estimated 30,000 more Jews were murdered at the ravine, along with about 30,000 other individuals from communities targeted by the Nazis—Ukrainian nationalists, Roma, Soviet communists, the mentally-challenged, hostages and prisoners of war. By the end of the German occupation of Kyiv, over 100,000 people lost their lives at Babyn Yar. The exact figures remain unknown.

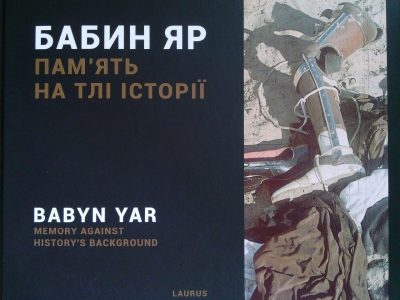

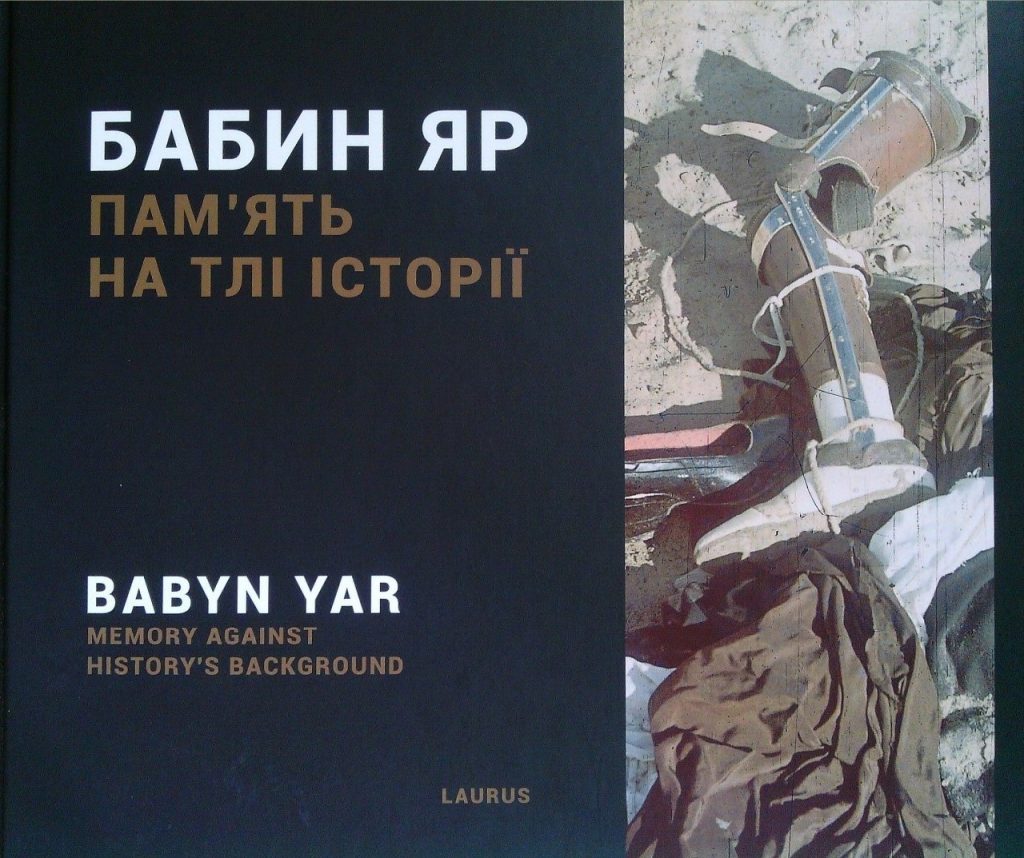

A newly published book, entitled Babyn Yar: Memory Against History’s Background and edited by Vitaliy Nakhmanovych, lead researcher of the Kyiv City History Museum and executive secretary of the Babyn Yar Public Committee, appreciably adds to our understanding of the grim heritage of Babyn Yar. The book explores the site’s complex history from the days before its name became synonymous with a killing site to current efforts to create a necropolis to honor its many victims.

“Any person can take the book and look at Babyn Yar in a new way,” said Nakhmanovych. “It is not only the history of the Jews, but it is also a book on historical memory…It is a reflection of what is happening throughout Ukraine.”

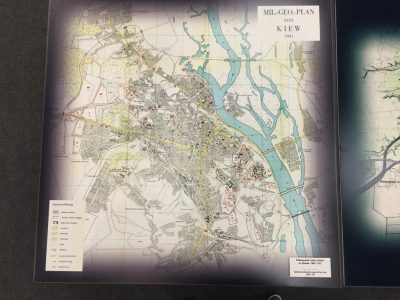

Geared toward a general readership with little knowledge of Babyn Yar, the bi-lingual (Ukrainian and English) volume draws on an exhibition the museum held in the fall of 2016 to commemorate the 75th anniversary of Babyn Yar. Richly illustrated with photos and maps that explore the site’s past and changing topography, the book also provides faces and names to Babyn Yar’s victims and to those Kyiv residents who risked their lives to save them.

The book also reproduces the design plans of the top prizewinners of an international architectural competition held last year to create a memorial park at Babyn Yar. Sponsored by the Ukrainian Jewish Encounter, the competition was held under the auspices of the International Union of Architects and several Ukrainian institutions. A section at the end provides artists’ renditions of Babyn Yar.

A lengthy chapter with various subsections places Babyn Yar within a larger historical context by chronologically reviewing the events that took place there.

For many centuries Babyn Yar was a sparsely populated outskirt of Kyiv, with the Kyrylivska Church, built in 1140, as its main landmark. In the second half of the 19th century, the area became incorporated into Kyiv’s Lukianivka district. The renowned Kyiv businessman Israel Brodsky funded the construction of a Jewish hospital and campus in the area in 1884-1885. In later years, land was allocated for Orthodox, Jewish, Karaite and Mohammedan graveyards, as well as for the Bratske [Fraternal] Cemetery. From the middle of the nineteenth century, a large territory called Syrets was used for summer military camps.

According to Nakhmanovych, in the 1930s, victims of Ukraine’s Holodomor [Famine] were buried at Bratske Cemetery in unmarked mass graves. Individuals tortured by the NKVD, the Soviet secret police, were secretly buried at the Lukianivske Orthodox Cemetery. Soviet authorities decided to create a sports facility at Babyn Yar in the early 1940s, but plans were cancelled due to the outbreak of the German-Soviet War.

Nakhmanovych’s treatment of the war years provides an account of how the site was transformed into a locale of massive and shockingly accelerated executions.

In a section on the destruction of Kyiv’s Jewish population, he writes that Jews began to arrive at Babyn Yar on the morning of 29 September 1941 from the city’s various districts. As they arrived at Bratske Cemetery, their money, documents, and valuables were confiscated. By 6 p.m. the Germans had murdered 22,000 Jews. By the end of the next day, 33,771 Kyiv Jews had perished at Babyn Yar.

Nakhmanovych also treats the fate of the Roma, Ukrainian nationalists, the Soviet underground, and psychiatric hospital patients in separate sections. Readers will learn how non-Jews fared under the Nazi occupation, and how first the Germans, and then the Soviets, tried to conceal the crimes that took place at Babyn Yar. The book includes a discussion of the Kurenivka disaster of 1961, the result of not only an ill-fated attempt to connect two parts of the city, but also “to wipe out the memory of the Kyiv Jew’s tragedy.”

Those Kyiv residents who risked their lives to save Jews are often overlooked in discussions about Babyn Yar. Nakhmanovych devotes a section on steps that have been taken to honor their courage.

Nazi policy in Eastern Europe was particularly savage. Unlike in other European countries that the Nazis occupied, the price for helping or harboring Jews in the East was death. Ukraine currently ranks fourth among the nations whose citizens—2,515 thus far—were awarded the title of Righteous Among the Nations, a recognition bestowed by the State of Israel on non-Jews who saved Jews during World War II.

During the Soviet period, however, authorities tried to keep secret the extermination of Jews during the war, and consequently recognition practices did not occur in the USSR, notes Nakhmanovych. It was not until 1988, in the era of Perestroika, that the Kyiv Society of Jewish Culture and its first organization, the “Memory of Babyn Yar” foundation, began to search for the Righteous on the territory of Ukraine. In April 1989, the council introduced an honorary public title called “Righteous of Babyn Yar”. The first individuals to receive that title were an Orthodox priest, Oleksiy Hlaholiev (posthumously) and members of his family.

As of today, 662 individuals have been awarded the title “Righteous of Babyn Yar”. Since then, the council has sent information about their identified rescuers to Yad Vashem, Israel’s official memorial to the victims of the Holocaust, which examines and evaluates each case to determine whether they will be recognized by the Israeli state. One hundred and fifty of these individuals have been deemed Righteous Among the Nations.

The challenge that faces Ukraine today is to properly pay homage to Babyn Yar’s complex past. Over the years, each community whose members suffered at Babyn Yar has erected memorials to honor their dead, creating a chaotic landscape of memorials. Local residents continue to use the site as a recreational park, even if they know the horrors that occurred there.

Government officials and the local Jewish community are still undecided about what form a proper acknowledgement should take—larger structures or museums, sometimes favored in the West, or more understated spaces that facilitate a reflection of place and time.

Nakhmanovych believes the disagreements over Babyn Yar mirror what is happening in other locales throughout Ukraine over historical memory. A resolution there would provide guidance for the rest of the country.

“We have to create mechanisms for resolving conflicts,” Nahkmanovych said. “If we can do it at Babyn Yar, we can do it at other places.”

This important new catalogue was unveiled at the Arsenal Book Festival in Kyiv in May during a panel that discussed the growing body of groundbreaking literature dedicated to Ukraine and its Jewish community. The works discussed were those financially supported by the UJE and the Ukrainian publishing houses, Dukh I Litra and Laurus, which published Nakhmanovych’s book

Along with the catalogue, a virtual tour of the exhibition is available on the Babyn Yar Public Committee’s website.

Photos and video from a panel discussion at Kyiv’s Arsenal Book Festival dedicated to Ukraine and its Jewish community. Works discussed were those financially supported by the Ukrainian Jewish Encounter and the Ukrainian publishing houses, Dukh I Litra and Laurus.

Watch the video of the panel discussion (in Ukrainian)

Iryna Slavinska, Moderator, Hromadske Radio

Natalia A. Feduschak, Director of Communications, Ukrainian Jewish Encounter.

Vladislav Hrynevych, Co-editor of Babyn Yar: History and Memory.

Oksana Forostyna, Translator, Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence.

Leonid Finberg, Publisher, Dukh I Litra.

Iryna Slavinska, Moderator, Hromadske Radio.

Natalia A. Feduschak, Director of Communications, Ukrainian Jewish Encounter.

Vladyslav Hrynevych, Co-editor of Babyn Yar: History and Memory.

Oksana Forostyna, Translator, Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence.

Leonid Finberg, Publisher, Dukh I Litra.

Iryna Slavinska, Moderator, Hromadske Radio.

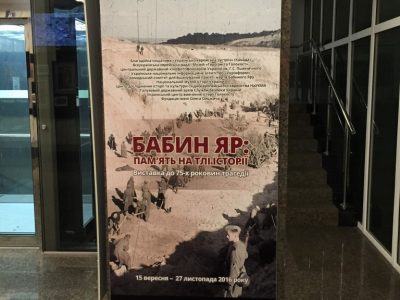

The exhibition on which the book Babyn Yar: Memory Against History’s Background is based, took place at Kyiv’s History Museum in honor of the 75th anniversary of Babyn Yar. Below are some photos and video from that exhibit, which ran from 15 September 2015 to 27 November 2017.

Text: Natalia A. Feduschak

Video and photos: UJE Kyiv office and Natalia A. Feduschak

Babyn Yar Exhibit videos courtesy of Vitaliy Nakhmanovych