"Before the Bolshevik coup, relations between Jews and Ukrainians were very warm," says the translator of the "Stawiszcze Memorial Book"

[Editor's note: Russia's unprovoked and criminal war against Ukraine suspended the regular work of many organizations, reorienting their efforts. So it is with the Ukrainian Jewish Encounter. We are occasionally running interviews and articles done before the beginning of the war, which reflect the myriad of interests undertaken by Ukrainian journalists, scholars and writers.]

What was life like for Jews in a small town in the Kyiv region in the late nineteenth–early twentieth centuries?

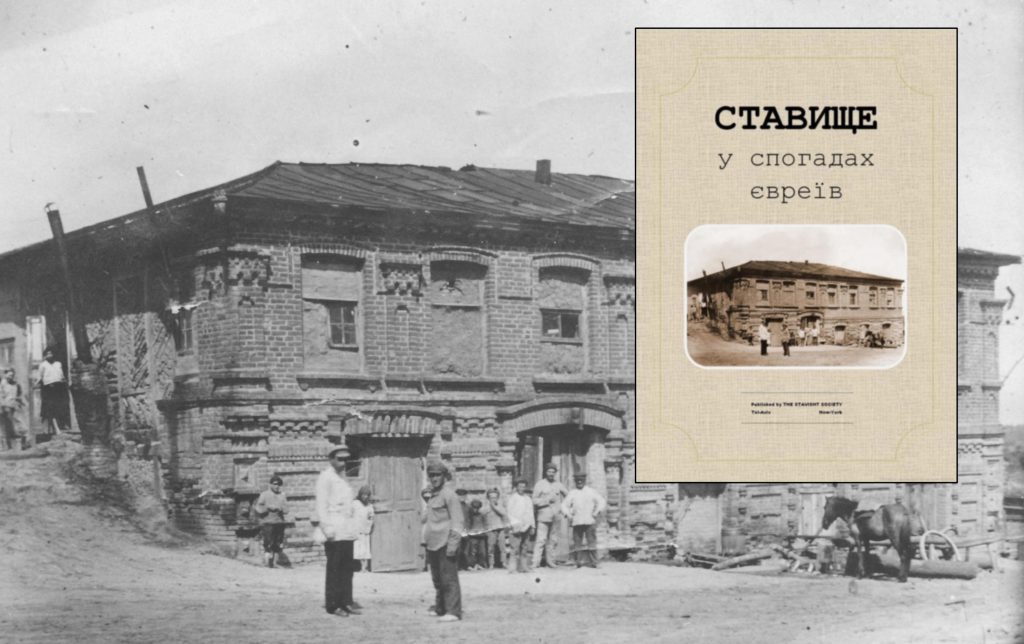

On the "Encounters" program, dedicated to Ukrainian-Jewish relations, we talked about this with Serhii Plakhotniuk, the translator of the Stawiszcze Memorial Book (released in Ukrainian under the title Stavyshche in the Recollections of Jews).

The history of the large village of Stavyshche, Kyiv region

Vasyl Shandro: What is this small town, Stavyshche? Tell us a bit about it. As I understand it, you were born there, and that was one of the reasons why you translated this book from English. What kind of town is it today?

Serhii Plakhotniuk: Stavyshche is a small town in the southern part of Kyiv oblast with a population of nearly 7,000. This urban-type settlement is the center of the Stavyshche community that was formed one year ago. The community is trying to expand and go forward.

Vasyl Shandro: Was this urban-type settlement once a small town, or was it always a large village?

Serhii Plakhotniuk: It was a village even during the period of Soviet rule. But at the beginning of the twentieth century, it was a small town with a population roughly the same as it is now. That is, after a hundred years, the population has remained at practically the same level, if one can point to such a historico-demographic gap.

Historical monuments in Stavyshche

Vasyl Shandro: We will be talking about the early twentieth century. The book that you translated concerns the late nineteenth–early twentieth centuries. What interesting things were in Stavyshche and are still found there? Have some important monuments of local, regional, or national significance been preserved? Is Stavyshche a large village that is interesting to tourists, for example?

Serhii Plakhotniuk: For me, it has always been interesting. That's why I began working on this issue, researching the history and trying to create some kind of attractive picture of Stavyshche. Since 2015 I have headed the Facebook group Stavyshchestables, and eventually, I started a YouTube channel in order to preserve my discoveries.

If we are talking about natural monuments, then the largest one is Stavyshche Park, which was founded by Count Branicki in 1857, for which he invited the well-known botanist and naturalist Antoni Andrzejowski.

If we are talking about architectural monuments, then these are mostly of Polish provenance. Branicki Hospital was built with funds from the estate of Aleksandra Branicka. Construction began in 1911, and it was completed under the Bolsheviks. From above, it resembles a biplane — that is how Count Branicki marked his fascination with aviation, which was then in the early stage of development.

One hundred and twenty-five years ago, a two-storey school was built in Stavyshche's satellite village of Rozkishna, also by the Branickis.

Vasyl Shandro: What are the Stavyshche stables?

Serhii Plakhotniuk: It's a kind of allegory. Since Count Branicki raised horses, there were stables. So, this is an allusion to the stables owned by Count Branicki, as a historical thematic group, and to the Augean Stables — the current one.

What is the story behind the publication of the Stawiszcze Memorial Book?

Vasyl Shandro: The Stawiszcze Memorial Book. What is it? How did you find out about it? Who compiled it, and when was it published?

Serhii Plakhotniuk: When the Jews left Stavyshche after the Bolshevik coup of 1917, the Stavyshche Jews in New York had their own society, whose members helped one another in the emigration. In 1956, these Jews from Stavyshche got together to decide how to honor their hometown. They decided to publish a memorial book in order to preserve their recollections of life in Stavyshche for their descendants. In general, these are fond reminiscences about Stavyshche, their unforgettable fatherland.

Vasyl Shandro: How did you find this book?

Serhii Plakhotniuk: I found it by accident. I began searching the Internet for something about Stavyshche in English or German, and on the website Yizkor Book Project I came across the English version of this book. It had first appeared in Yiddish, but it was translated into English so that it would be accessible to a larger readership. This was around 2010. I began translating it but put it aside. In 2016, I met Viktor Khimenko from St. Petersburg, who was also interested in the history of Stavyshche. He gave me the motivation to finish the translation and publish it, so that most of the residents of Stavyshche would learn about its history that they were never taught in school or at university.

Vasyl Shandro: Who compiled this book, and who collected these reminiscences in America?

Serhii Plakhotniuk: In the States, Arthur Schechter headed the project to collect as many reminiscences as possible, and natives of Stavyshche, Jews, wrote whatever they could recall. Many reminiscences were intertwined with many names and such details that I was a bit surprised because thirty to fifty years had passed, and people still remembered so many names and details about what had taken place in Stavyshche in the late nineteenth–early twentieth centuries.

What was the Jewish community of Stavyshche like in the nineteenth century?

Vasyl Shandro: I am talking specifically about the late nineteenth century. Do these recollections reveal what the community was like? Are there any studies about the number of Jews who lived in Stavyshche?

Serhii Plakhotniuk: According to the 1897 census, Jews comprised half of the population of Stavyshche; nearly 4,000 Jews were recorded at the time. And, of course, the number increased by the First World War. There are descriptions stating that before the war, 8,000 Jews lived in Stavyshche. At the time, the population of Stavyshche was close to 16,000. But this is not a precise figure.

According to the 1897 census, Jews comprised half of the population of Stavyshche

Vasyl Shandro: After the First World War and the Bolshevik occupation of Ukraine, did the entire community emigrate?

Serhii Plakhotniuk: No, only those who could left right away, especially those with relatives in America. The standard route of Jewish emigrants was through Odesa to the Romanian border. There, they waited for some funds from their relatives and documents that would permit them to board a ship to America. But not everyone left; some people even tried to return. They hid from the pogroms in neighboring small towns, especially Bila Tserkva, Volodarka — wherever they could. They hid in the homes of Ukrainian friends who were not afraid to shelter them.

Vasyl Shandro: Do these stories exist? Are these stories of people who are still alive, or did you read their reminiscences?

Serhii Plakhotniuk: I read recollections, and they made me realize that, prior to these events, relations between Jews and Ukrainians in Stavyshche were very warm. There were none of the confrontations that emerged after the Bolshevik coup, when these lands, situated quite far from Kyiv, were plunged into chaos.

Jewish religious structures in Stavyshche

Vasyl Shandro: What do we know about Jewish life in Stavyshche? What did they do, what occupations did they pursue? Were there any educational institutions, religious buildings — synagogues?

Serhii Plakhotniuk: In their reminiscences, the Jews joked that there were as many synagogues in Stavyshche as there were continents. There was the Great Synagogue, the oldest and evidently made of wood. There was a beit midrash [house of study — Ed.], which is still standing today. The first floor of the beit midrash housed a school for Jewish boys, and on the second floor — a synagogue.

Vasyl Shandro: It was a multifunctional building?

Serhii Plakhotniuk: Yes, the second storeys of shops were generally used for synagogues because it was expensive to maintain a separate synagogue building. It was more sensible to make do with an existing building, as I understood from the reminiscences.

There were also four kloyzn — small synagogues that appeared in Stavyshche during various periods, and each one served a different social stratum and the followers of various branches of Judaism. Some were for ordinary people, craftsmen; others — for local wealthy individuals, the elite. The names of the kloyzn were Zionist, Makariv, Sokoliv, and Talne. Each synagogue had its own audience.

Jewish occupations in Stavyshche

Vasyl Shandro: What occupations did Jews pursue, what did they produce, where did they work? Do we know something about this?

Serhii Plakhotniuk: There were various kinds of occupations that met the needs of the Stavyshche inhabitants: bootmakers, tailors, blacksmiths, and other trades. They owned shops that sold fabric, candy, or some kind of kosher food, clothing, records — everything that people needed. From the reminiscences, I understood that the wealthiest Jews were those who sold eggs.

Vasyl Shandro: Why?

Serhii Plakhotniuk: They were able to deliver them to Odesa, to Kyiv; they sold them in all directions. Even today, selling eggs is a profitable business.

There was an interesting business: the sale of kosher crackling made of goose skin. Jews recalled that this crackling was famous even in Zhashkiv [Uman raion — Trans.]; carters delivered them especially to the bazaar in Zhashkiv.

Incidentally, there were many carters in Stavyshche, and, as I understand it, they were treated a bit dismissively because it was thought that such a person had not achieved any profession, but had simply purchased any old horse and wagon and was earning a simple living. But everyone knew the carters in Stavyshche, and they each had a nickname.

Descendants of Jews in Stavyshche

Vasyl Shandro: Some Jews went to America, but some remained in Stavyshche. Is there still a Jewish community in the village, and do its members know all these stories? Or was it a revelation for the Jews of Stavyshche when you found this book and translated it?

Serhii Plakhotniuk: Clearly, it was a revelation. The Jewish community in Stavyshche is small, and they all came in a group to the book launch in 2017. The museum auditorium was full, and everyone listened closely to everything that I recounted at the launch. Some 20 or 40 people consider themselves the Jewish community in Stavyshche. They hold meetings and take care of the Jewish cemetery, for example.

Vasyl Shandro: There's a cemetery, right?

Serhii Plakhotniuk: Yes, there is still a Jewish cemetery in Rozkishna. With the assistance of the U.S. Commission for the Preservation of America's Heritage Abroad, it was brought to some sort of order. It was fenced in, and a commemorative plaque indicating that this is a Jewish cemetery was installed near the entrance. This plaque was unveiled by a descendant of Stavyshche Jews, Richard Weisberg, who is a member of the commission.

Vasyl Shandro: You mean the descendants of those who left Stavyshche visited the village after the declaration of independence?

Serhii Plakhotniuk: Yes, we know that the first one came in 1994, after Ukraine became independent. At the time, Martha Lear came from the USA. She was searching for information about Jews who were killed during the Second World War, who had been shot at the Revykha tract near the village of Rozkishna. After this visit, The New York Times published a long article about it.

Vasyl Shandro: In other words, a proportion of Stavyshche Jews perished during the Second World War?

Serhii Plakhotniuk: Yes. In the fall of 1941, roughly 200 Jews were shot in a forest. Today there are two commemorative markers at the Jewish cemetery in Rozkishna.

What are the best places to visit in Stavyshche?

Vasyl Shandro: What monuments remain, perhaps architectural ones, maybe some artifacts or some iconic places associated with Jewish life in Stavyshche and in the village of Rozkishna, which is a satellite of Stavyshche? What can visitors see? Are there any museums or tours to specific places?

Serhii Plakhotniuk: The museum in Stavyshche always gladly welcomes guests, even on weekends. Last summer Sara Gordon came from Berlin to see the places where her ancestors were born, and the museum conducted a tour on Saturday, on the weekend. Have any monuments been preserved? I have already mentioned the beit midrash, which today houses a dormitory for pupils who attend the school in Stavyshche and live far away. The Jewish cemetery has been preserved. There is also a clay house dating to around 1914, which is located in the center of Stavyshche.

I failed to mention that Jews once occupied all of downtown Stavyshche. They lived near the count's palace, so they were focused on earning money from the stewards, those who managed the count's estate. There was a square in downtown Stavyshche, and fairs took place there on Tuesdays and Fridays. Ukrainians lived in Pshinka; at the time, it was the outskirts, two or three kilometers from downtown Stavyshche. The small town was clearly divided into a Jewish and non-Jewish part. Located downtown were part of the count's palace with a large park, then the town's Jewish cemetery, and then the peasants' homes.

Vasyl Shandro: Are you saying that of all the hundred-year-old buildings, today, only this house and the synagogue where people gather still exist?

Serhii Plakhotniuk: There is also a red, two-storey brick building that is located a bit down from the center of Stavyshche. It is in a neglected state because it passed into private hands, and the owner is not taking care of it at all. For the past few years, I have been trying to get the local authorities to try and change the situation.

The bricks that were used to build this place are dated 1902. This two-storey building has a non-standard architectural design. There are five windows on the first floor and seven on the second floor, and they are completely unsymmetrical, which may indicate that perhaps the first floor was built out of brick and had been constructed for some other purpose, maybe residential. Jews typically used the first floor for a shop, and the second for their own accommodations.

References to Ukrainians in the book

Vasyl Shandro: What interesting things did you learn from these reminiscences? For example, some toponyms or references to Ukrainian fellow townspeople whose descendants still live in Stavyshche today? Did you come across any interesting accounts? Why did you compile a glossary for this book?

Serhii Plakhotniuk: I had to compile a glossary in order to explain certain perplexing words, so that readers can understand what they're reading. I also drew up a list of synagogues for the book and tried to collect all known information about them — their names and the story of their emergence in Stavyshche.

Vasyl Shandro: Are there any references to Ukrainians whose descendants may still be living in Stavyshche?

Serhii Plakhotniuk: There are several references to Ukrainians who helped Jews sit out the pogroms in their basements, cellars, or attics. The atmosphere between Jews and Ukrainians was amicable; the pogroms were perpetrated by outsiders, who appeared from various directions.

Where can one read Stavyshche in the Recollections of Jews?

Vasyl Shandro: Your translation of the book is freely available. Did you coordinate all the copyright issues with the copyright holders? In other words, is it officially freely available?

Serhii Plakhotniuk: My friend, Viktor Khimenko, helped me obtain permission from the copyright holders to translate and publish this book and since only 120 copies were printed, thanks to donations from patrons and crowdfunding, I uploaded it to Google Books where it is freely available. According to the conditions set by the copyright holders, I do not have the right to earn money from it; that's why I uploaded it for a larger readership that is interested.

Vasyl Shandro: So, we can provide a link to this book?

Serhii Plakhotniuk: Yes. I asked for reactions from some historians, and the book was praised for its quick and easy readability.

This program is created with the support of Ukrainian Jewish Encounter (UJE), a Canadian charitable non-profit organization.

Originally appeared in Ukrainian (Hromadske Radio podcast) here.

Translated from the Ukrainian by Marta D. Olynyk.