Between the "Whites" and the "Reds": Who carried out pogroms against the Jews during the Civil War?

Editor’s note: In 21-23 November 1918, an estimated 52-150 Jews were killed in a pogrom in Lviv during the Polish-Ukrainian War that followed World War One. In honor of the 100 year-anniversary of this horrific episode in Ukraine’s history, we offer an interview with historian Nadia Lipes that ran on Hromadske Radio’s UJE-supported Zustrichi program. She discussed in general anti-Jewish pogroms on Ukrainian lands that occurred between 1917-1919.

Andriy Kobalia: We are discussing the difficult topic of the anti-Jewish pogroms that took place during the Civil War.

“In Murovani Kurylivtsi more than sixty Jews were killed, and in Yaltushka eighteen young Jews and elderly men were maimed. Witnesses recounted the horrors. And the Jews prayed that this horde might not come to them.”

This is a passage from a document dated 1919 about the pogroms in the Kyiv region. This bloody wave began a hundred years ago. According to various estimates, it claimed from dozens to hundreds of thousands of lives in the Ukrainian lands.

According to historians, the pogroms against the Jews in the territories of contemporary Ukraine, Belarus, Lithuania, and Russia were a continuation of the antisemitic policies of the tsarist government.

Similar conflicts had occurred in these lands in 1881–1882. The Kishinev pogrom of 1903 claimed the lives of fifty Jews. More than eight hundred people were killed in the pogroms of 1905. As a result of these events, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries hundreds of thousands of Jews immigrated to the United States and Canada, and some settled in Palestine, where the State of Israel was later founded.

But the pogroms in 1917–21 differed from all the previous ones in that they took place during a period of turbulent historical changes. The tsarist government fell during the February Revolution of 1917. The Ukrainian Revolution and the war for Ukraine’s independence culminated in defeat, and tragic events took place on the ruins.

The historian Nadia Lipes and I discussed the complex topic of the anti-Jewish pogroms in the Ukrainian lands during the Civil War. This Kyivite and citizen of Ukraine has devoted the last few years to examining the archives of the commissions of the Jewish Civic Committee for the Relief of Pogrom Victims, which existed from 1920 to 1924, and was founded on the initiative of the Jewish community. Later the committee received support from the American-Jewish charitable organization known as the Joint, or Joint Distribution Committee (full name: the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee). These documents allow us to gain a partial understanding of what happened in 1917–1920.

Nadia Lipes: Who initially began to carry out these attacks? It was soldiers of the Russian army who, prior to this, had attacked the Jews of Galicia, which they had invaded during the First World War. Why? They were angry about losing the war. They also felt they had impunity. And here you have the Jews. The Jews were constantly being accused of espionage, they were sent away from the borders of the empire. No one would ask them any questions. These acts were also witnessed by local peasants, who did not want to do anything, but get something at the same time. To this one should add the stereotypes that existed during this period and earlier, according to which Jews always had everything. At the same time, it is not clear where they [these stereotypes] came from, because Jews were often worse off than their peasant neighbors. People believed “television” more than their very own eyes. And that was the way it was.

With every passing year the number of pogroms increased, but not the number of punishments. Occasionally, pogrom participants were shot demonstratively in specific locals for specific goals. They were often shot not for the pogroms but for violating orders. For example, there was an order for a soldier to remain at his post, but he went off and raped someone. Why was he shot? The execution was not for rape but for violating an order. And there you have it.

Andriy Kobalia: I think it would be worthwhile explaining to our listeners which years and territories we are talking about and to tell them about the main political forces of this period.

Nadia Lipes: We are talking about the period from 1917 to 1921. The pogroms started even earlier, when the tsarist government completely relinquished its positions. Aggression was launched by the retreating and returning soldiers of the tsarist army. The arrival of the Bolsheviks in some parts of Ukraine did not put a stop to these pogroms either, at least not right away. In fact, the only force that put a stop to the pogroms was the newly formed Soviet Union, but only because it would not be able to obtain money from the Western states. They had no desire whatsoever to save all the Jews. They simply understood that “he who pays the piper calls the tune.” Europe and America did not like the Jewish pogroms and therefore the pogroms were halted with their good and severe communist methods.

Andriy Kobalia: But can it be said that the Red Army, the Bolsheviks, did not take part in the pogroms?

Nadia Lipes: Of course not. For example, Budenny’s cavalry. They, too, carried out attacks, and afterwards officers and the command also punished the soldiers. Isaac Babel writes about this. The other thing is that they did not take such an active part.

Pogromists were divided into several types. Some were more interested in direct action—to attack and steal something. Not to kill. Some units of [Symon] Petliura’s troops were interested in killing, not in taking things, money, or tormenting, simply in killing, because “this tribe must be wiped off the face of the earth.” Sixty percent did whatever could possibly be done. Most pogroms took place in 1919. The soldiers of all armies were aware that there would hardly be any punishments for this; all armed formations began to launch attacks more frequently than in 1917 or 1918. Some simply robbed, some killed and raped, and some mistreated and killed.

Andriy Kobalia: Although the Bolsheviks declared officially that religion or national affiliation is secondary for them, Mykola Lazarovych, a historian at Chernivtsi University, claims that pogroms were characteristic of the Bolsheviks as well. This is what he writes about the pogroms of 1919:

“The terrible scenes of the Jewish pogrom that was carried out in Odesa by Red Army troops on 2 May were described by Ivan Bunin. The pogromists ‘burst in at night, dragged from beds and killed everyone whom they saw. People fled to the steppe, threw themselves into the sea, and they were chased and shot at—it was a real hunt.’ As a result, fourteen commissars and nearly thirty ordinary Jews were killed; many small shops were smashed. The Bohun Regiment, thanks to its violent pogromist inclinations, stormed through Jewish cities and towns. In particular, in early May it attacked Jews in the town of Zolotonosha, in Poltava Gubernia. Red Army soldiers also carried out pogroms in Klevan, in Volyn Gubernia; Berdychiv, Obukhiv, and Pohrebyshche in Kyiv Gubernia.”

Andriy Kobalia: In discussions about the participation of Petliura’s troops in the pogroms, a document dated January 1919 is often cited. In it Petliura orders that all participants in pogroms be punished. It also talks about the crucial need for investigations and a search for the guilty parties. At the same time, some historians say that Petliura simply could not control his troops. What do you think, was he an antisemite?

Nadia Lipes: Most likely, [Symon] Petliura himself was not an antisemite. It’s like the anecdote: “What do you think about Jews? I don’t think about them.” He had his own goals. Perhaps what was taking place all around troubled him as a person, but he realized that he could not do anything with his army. Initially, it was not Petliura who was against the pogroms but [Volodymyr] Vynnychenko. It was he who tried to stop some, but since he was absolutely an intellectual, he could not do anything. He took umbrage at everyone and left. Petliura accepted the situation that existed.

Absolutely everyone took part in the pogroms: Whites, Bolsheviks, and Petliura’s troops, and peasants and the inhabitants of neighboring gubernias. Of course, it is easier to kill someone you don’t know personally, but the majority of the pogromists knew the people whom they were attacking. This did not disconcert them. The biggest problem in these things was impunity. The pogromists knew that after the killing of an ordinary peasant there would be questions, but if they kill twenty-five local Jews—no questions would be asked. That’s all. And the soldiers of all the armies—the Whites, the Denikinites, the Petliurites, etc. knew this.

All subjects depended on the concrete formations that entered a city or village. In the case of Petliura, it could be some kind of organized action. And not because Petliura signed some documents; it was simply that his officers made such a decision. They, too, had their own task. The bloodiest pogroms were carried out by bandit groupings like Grigoriev’s. They swooped down and attacked. At first, they might send in a reconnoiterer, find themselves an interpreter from among the locals, learn where the rich Jews were living, and launch local attacks on these homes.

Everything depended on the period and the size of the gang. If there were twenty men, they would find the person who showed them where the Jews lived; they would swoop in, kill, and everything was over in three hours. Later, they would be replaced by someone else. If there were more than twenty men in a gang, they could enter a village or town for a long period of time and set up headquarters. In that case, they forced Jews to pay an indemnity; they [the Jews] could not manage this, then they would begin killing the hostages. Later, one gang would be dislodged by another, which would accuse the Jews of supporting the previous regime, and impose an indemnity on them. That is what happened in late 1918 and throughout all of 1919, in some places even until September 1920. But in 1920 it was more the Poles and White Guardists who were doing this.

[By 1920 the Army of the UNR had become weakened and demoralized. [Nestor] Makhno had gone over the Bolsheviks, and the majority of otamans had been killed or had gone over to the Bolsheviks. The Soviet-Polish war took place between September 1919 and March 1921, during which the Poles were on Ukrainian territory several times. In 1921 some White troops were based in the Crimea—Eds.].

Andriy Kobalia: The pogroms were not simply a phenomenon that arose in the territories of the former Russian Empire. Starting in the fall of 1918, when Austria-Hungary ceased to exist, pogroms against Jews also took place in Galicia. In late November 1918, immediately after Polish troops captured Lviv, a pogrom took place in the city, which claimed the lives of nearly a hundred Jews.

Some members of Jewish communities refused to flee from their cities and villages, and sought to organize self-defense detachments to protect Jews from being looted by every new, succeeding army that entered a city. Such detachments appeared in Odesa, Rivne, and Kremenchuk. After the Bolsheviks finally established control over the Ukrainian lands, both Soviet investigators and Jewish communities began to investigate the pogroms.

Nadia Lipes: It is interesting that the entire population did not treat the Jews equally badly, at least at the beginning. Many inhabitants lived alongside the Jews in neighboring homes and villages. The populace knew that Jews had nothing to eat, just like their neighbors. Sometimes a Jew was the only cobbler for three villages. In this case, it was economically advantageous to let a Jew live. But, starting in 1917, they witnessed impunity; later they began thinking that if they don’t kill a Jew, then someone else will. Why wait for someone else when you can grab something yourself?

Andriy Kobalia: Besides soldiers from various armies, local peasants also took part in the pogroms. The historian Viktor Dotsenko writes about their actions:

“Among the active participants of the pogroms were Ukrainian peasants, who regarded the Jews as some of the parties responsible for the Bolshevik policy of “war communism” and the lack of urban [manufactured—Trans.] goods in the countryside: matches, soap, kerosene, nails. These goods formed the heart of Jewish trade stalls in the small towns of Right-Bank Ukraine. The trade deficit led to signs of speculation, and the latter led to the desire to settle the score with the despised Jews. In addition, pogromist moods were also influenced by the destruction of the traditional, prewar rural order, in which the Jews performed the role of petty tradesmen: carpenters, saddlers, cobblers, etc. Jews were forced to retrain themselves as intermediary traders of manufactured goods, which led them to descend to the level of “bag men” [mishechnyky] in the peasants’ eyes. This transformed the Jew into a target of potential looting and confiscation of illegally gained wealth. Furthermore, the Bolshevik policies of food levies, the organization of communes, and the establishment of Soviet power in villages and raions led to the dangerous identification of Jews with Bolsheviks by the peasants.”

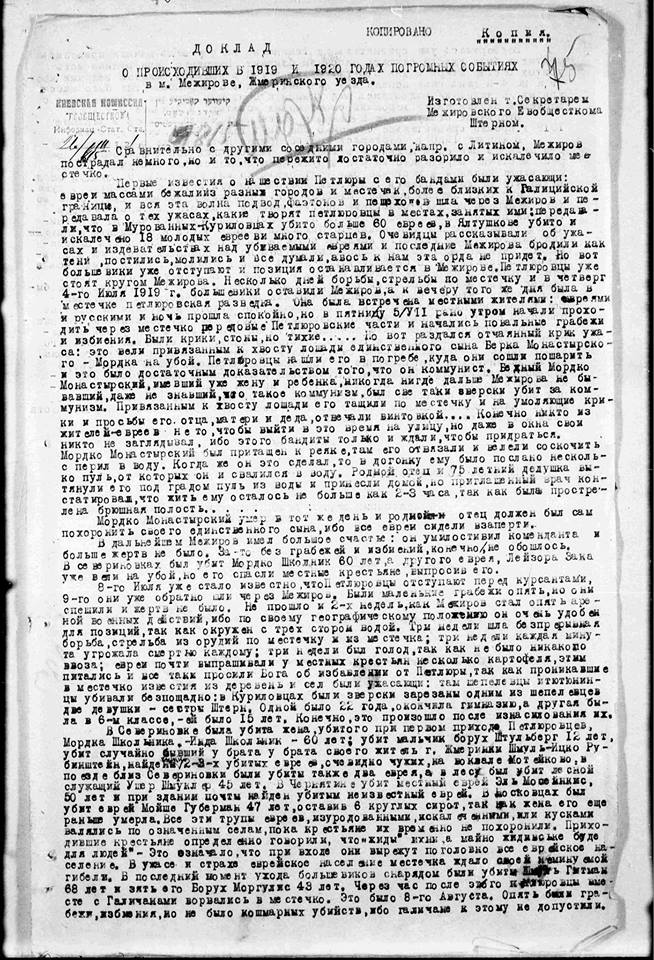

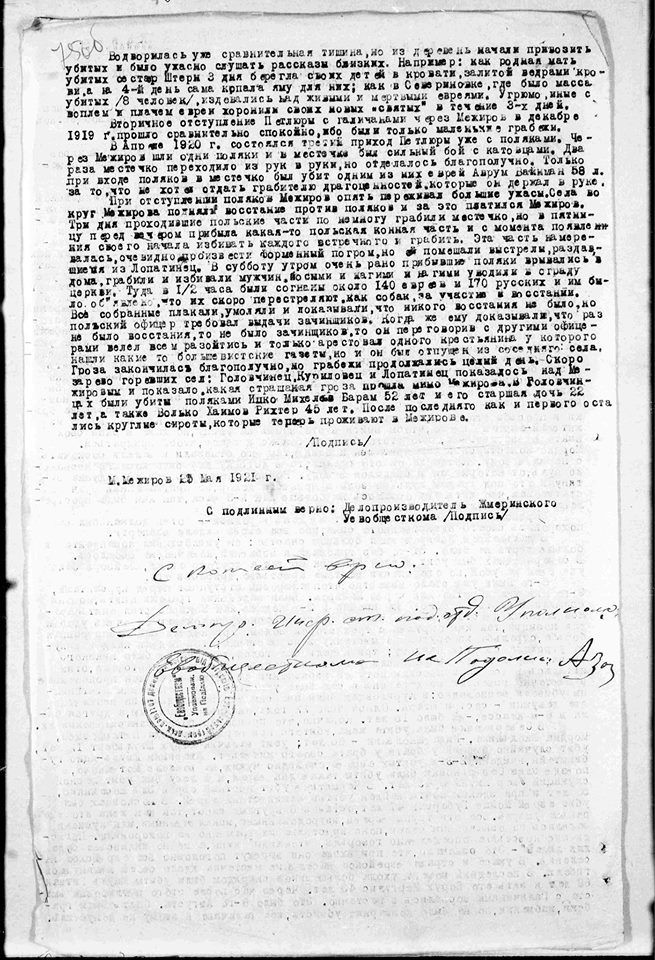

Andriy Kobalia: The historian Nadia Lipes believes that the stereotypical image of the “Jewish communist” is important in understanding the pogroms of the Civil War period. In her view, it is important to hear about the history of the pogrom that took place in the town of Mezhyriv, which she learned about from the documents of the Jewish Committee for the Relief of Pogrom Victims, based in Kyiv raion. We began our program with this document. Here is the full text:

“Report on the pogroms that took place in 1919–1920 in the city of Mezhyriv, Zhmerynka County. In comparison to other cities, Mezhyriv did not suffer much, but the war nevertheless devastated and crippled the entire town. The first news of the invasion of Petliura and his gangs was horrifying. The Jews fled from the Petliurite troops into towns that were closer to the border with Galicia. That entire wave went through Mezhyriv and reported about those horrors that were taking place in cities where the Petliurites were. They reported that in Murovani Kurylivtsi more than sixty Jews were killed, in Yaltushka eighteen young Jews and elderly men were maimed. Eyewitnesses recounted the horrors. And the Jews prayed that maybe this horde would not come to them.

The Bolsheviks retreated later, and the Petliurites approached the city. A few days of shooting at the city, and on Thursday, 4 June 1919, the Bolsheviks abandoned it. And toward evening of the same day a Petliurite reconnaissance group was in the town. It was met by the local residents, Jews and Russians. The night passed quietly. On Friday vanguard Petliurite units began to pass through the city, and looting and beatings began. There were shouts and groans, but quiet ones.

But there came a cry of horror: the only son of Berk Monastyrsky, tied to the tail of a horse, was being led to slaughter. The Petliurites had found him in a cellar that they had entered to rummage around. This was ample proof that he was a communist. Poor Mortko Monastyrsky, who already had children and a wife, had never traveled farther than Mezhyriv, and did not know what communism was, was grabbed and killed savagely for communism.

Tied to the tail of a horse, he was dragged through the town. And to the pleading cries of his father, mother, and grandfather, they replied with rifles. Of course, none of the Jewish residents dared go outside. Mortko was dragged to the river, untied, and pushed into the water. When he was in the water, a few bullets were sent after him, from which he ultimately fell into the water.

His father and 75-year-old grandfather dragged him out under a hail of bullets, and carried him home. But a doctor who was summoned stated that he had no more than two or three hours left to live because he had been shot in the abdominal cavity. Mortko died that day. And his father was forced to bury him by himself because all the Jews were sitting locked [inside their houses]. Hereinafter Mezhyriv had good fortune, it appeased the commandant, and there were no more victims, but it was not possible to avoid robberies and beatings.”

Nadia Lipes: Using the example of the town of Mezhyriv, we see who was considered a communist. This fellow barely spoke Russian or Ukrainian. Then there was the issue of the those 60-year-old grandpas. In Severynivka the wife of a comrade, who was killed during the first arrival of the Petliurites, was killed. Someone was killed by a random shot, 12-year-old children were killed. Girls were raped then killed.

This is but one page from a thousand files with which I am familiar. This account pertains to the Kyiv raion commission of the Jewish Civic Committee for the Relief of Pogrom Victims. It was drawn up by Shtern, secretary of the Mezhyriv Jewish Civic Committee. These committees were created in all the large Jewish cities, and they dealt with eyewitness statements of the residents of the affected cities and with the distribution of relief that was sent from the Jewish-American Joint fund.

Many families ended up on different sides of the ocean because of the First World War. From 1914 to 1917 there was no correspondence. Then rumors about pogroms in these territories trickled to America. American Jews launched a feverish search for their remaining relatives, and the other way around: Those who had survived somehow searched for their relatives overseas, so that they would get them out.

Andriy Kobalia: Reports painstakingly reveal all the parties that carried out pogroms, from Petliurites to Reds. Nadia Lipes says that the historical importance of the documents of the Jewish Civic Committee is high, inasmuch as in the early 1920s the Bolshevik government wielded practically no influence on their content.

Nadia Lipes: I have files from the Vinnytsia, Odesa, and Kyiv archives. These are immense fonds containing between 400 and 500 files. Some of them are simply [the minutes] of meetings of the committee, along the lines of “we have decided to allocate this amount of money.” But I saw there lists of those killed or those who had been given assistance. Many Jews died of wounds; raped girls ended their lives by suicide; children were left orphaned and died of starvation because their parents had perished; there was simply no one to feed them. In Zhytomyr half of the people registered at the synagogue starved to death. That’s how it is written: “starved to death” or “died of exhaustion.” Neither did all those epidemics of influenza and typhus in 1919 and 1920 come out of the blue. The body can no longer resist all this. You may not kill a man, but if you steal everything from this man, evict him in the winter, and burn down his home, the probability that he and his small children will survive drops to zero.

Andriy Kobalia: You spoke about these committees that existed in larger gubernial cities. Did you find the people who took part in the pogroms? How many people are we talking about?

Nadia Lipes: Of course, all the participants were never found. This committee existed until 1924. If anyone knew that someone had killed another in 1917–1920, he would grab him and bring him to the militia. He would be interrogated. In 1924 there was no brutal torture. The interrogation was humane. A man said that he was not the only one, this one and that one were with me. Then they tried everyone en masse. Afterwards one was released for lack of evidence, or a man straightened out, or “was a 17-year-old boy.”

Andriy Kobalia: The number of pogroms began to decline after the conclusion of the active phase of the war. At the same time, the majority of the political players disappeared. In the spring of that year Denikin, the White Army general, fled to Europe, and his successor, Wrangel, died in emigration in Brussels. General Symon Petliura was assassinated by a Russian anarchist in Paris in May 1926. Eight years later Nestor Makhno died of tuberculosis in this same city. Local armed formations were destroyed, and the Bolsheviks were able to capture all the Ukrainian lands.

More than 800 anti-Jewish pogroms took place in 1917–1920 in the territories of the former Russian Empire, which, according to various estimates, claimed the lives of 50,000 to 100,000 people.

In 1925 a monument to the victims of the 1919 Proskuriv pogrom was unveiled in Khmelnytsky; it was reconstructed in 2000. A monument dedicated to the pogrom in the village of Hermanivka, Kyiv oblast, was erected in August 2012. There is also a monument at the Jewish cemetery in Fastiv. Unfortunately, in the majority of cities and villages where anti-Jewish pogroms occurred there are no commemorative sites that would remind their inhabitants of the events that took place in the years 1917–1920.

The photographs of the documents about the pogrom in Mezhyriv (from the State Archive of Kyiv Oblast) were provided by Nadia Lipes at the request of the program administrators.

This program was made possible by the Canadian non-profit organization Ukrainian Jewish Encounter.

Originally appeared in Ukrainian (Hromadske Radio podcast) here.

Translated from the Ukrainian and the Russian by Marta D. Olynyk.

Edited by Peter Bejger.

NOTE: UJE does not necessarily endorse opinions expressed in articles and other materials published on its website and social media pages. Such materials are posted to promote discussion related to Ukrainian-Jewish interactions and relations. The website and social media pages will be places of information that reflect varied viewpoints.