Borys Zabarko: New books on the Holocaust in Ukraine for foreign audiences

Recent sociological surveys have shown that more than thirty percent of Europeans and more than half of the world’s population know nothing about the Holocaust.

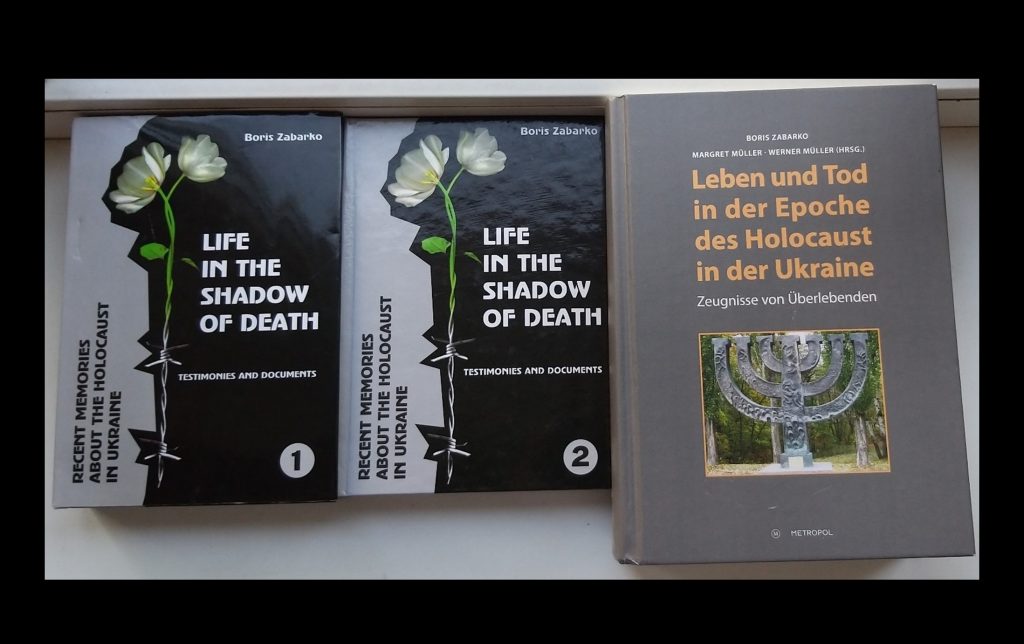

On the 75th anniversary of the end of the Holocaust (the Catastrophe, the Shoah) and the great victory over Nazism during the Second World War in Europe, Dr. Borys Zabarko, who survived the Holocaust in the Sharhorod ghetto (Vinnytsia oblast) and is the head the All-Ukrainian Association of Jews—Former Prisoners of Ghetto and Nazi Concentration Camps and the director of the “Memory of the Catastrophe” scholarly and educational center, prepared and published for the Western world new books in the English and German languages containing the recollections of victims from the preceding generation; those who managed by some miracle to survive in the Nazi-occupied territories of Ukraine in 1941–1944 and whose lives thereafter were marked by a struggle with the consequences of the Catastrophe. One is the book Life in the Shadow of Death: Recent Memories about the Holocaust in Ukraine; Testimonies and Documents (2 vols., Melitopol, 2019; 1242 pp.). The second is a book co-authored with his German colleagues and friends from Cologne, Margret and Werner Müller: Leben und Tod in der Epoche des Holocaust in der Ukraine: Zeugnisse von Überlebenden (Life and Death in the Era of the Holocaust in Ukraine: Survivor Testimonies, Berlin, 2019, 1100 pp.)

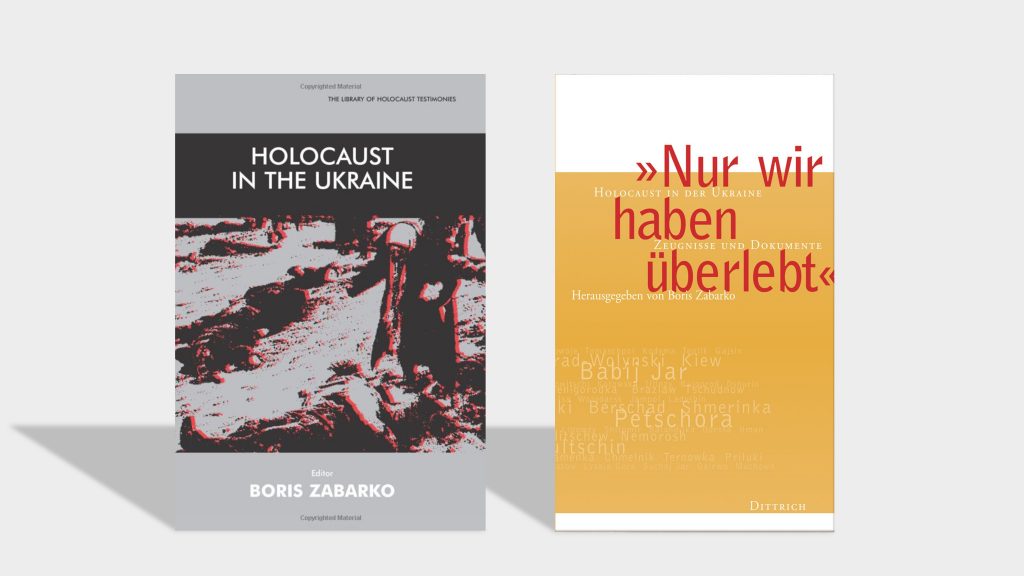

These publications continue and develop the series of books published earlier by him in Germany and the UK: Nur wir haben überlebt: Holocaust in der Ukraine; Zeugnisse und Documente (Only We Have Remained Alive: Testimonies and Documents, Cologne, 2004, 478 pp.; 2016, 576 pp.) and Holocaust in the Ukraine (London and Portland, 2005, 394 pp.).

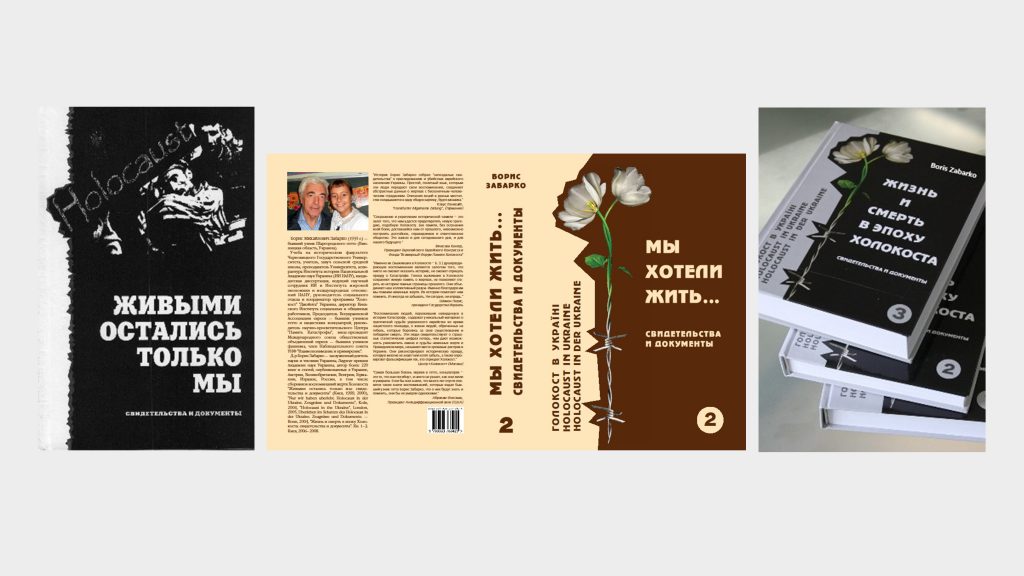

Unlike those publications, which have become bibliographic rarities, the new books contain the translated recollections of Holocaust witnesses extracted from six volumes of the series Kholokost v Ukraine: 1941–1944 (Zhivymi ostalis′ tol′ko my (Only We Have Remained Alive, Kyiv, 1999–2000, 578 pp.); Zhizn′ i smert′ v epokhu Kholokosta: Svidetel′stva i dokumenty (Life and Death in the Era of the Holocaust: Testimonies and Documents, 3 vols., Kyiv, 2006–2008, 1855 pp.); My khoteli zhit′: Svidetel′stva i dokumenty (We Wanted to Live: Testimonies and Documents, 2 vols., Kyiv, 2013–2014, 1384 pp.). They encompass the entire territory of Ukraine, including all the occupation zones (Reichskommissariat Ukraine, Distrikt Galizien, the war zone, Transnistria, Transcarpathia, and the Crimea), and are arranged in chronological order.

The books are based on a solid scholarly apparatus, which comprises about a quarter of the total output. This consists of detailed factual notes to the main text, bolstered by links to a scholarly and documentary database, bibliographies of literature in different languages, maps, an index, tables, a glossary, and other scholarly reference materials that help readers navigate through data related to a particular area, time, name, or event, in order to obtain more complete and truthful information about the Holocaust in Ukraine. Given that the books are intended for foreign readers, introductory articles to them were written by the well-known scholars Dr. Dieter Pohl (Germany), Dr. Karel Berkhoff (Netherlands), and Dr. Martin Dean (USA).

The purpose of the books is to recount the tragedy and resistance of Ukrainian Jewry during the war years and the Holocaust, as a component of the global Jewish and Ukrainian communities; the inhuman sufferings, torments, and lives of ordinary people who were doomed to die but resisted, fought for their existence, preserved their humanity, and conquered death.

Holocaust survivors—after a long, forced silence (not only because they could not endure the terrible past and step over its abyss, but because the state that left them to face the Nazis alone did not need their truth)—told their story, describing above all their personal experiences. They talked about themselves, their families and friends; about pre-war Jewish life that the Nazis destroyed; about their rescuers, people who were indifferent, and murderers and their helpers; about good and evil, sin and guilt, hatred and mutual help, meanness and forgiveness, despair and hope, vileness and heroism, crime and punishment, disillusionment and faith, suffering, and a determination to survive in spite of everything.

The testimonies of people who passed through the “valley of the shadow of death” and survived the Holocaust in a long-suffering country that lost 1.5 million of its men, women, children, and the elderly just because they had been born Jews, make it possible to illustrate the broad panorama of the total destruction of the Jews on a personal level, using the examples of the fate that befell individual victims, and to name and preserve in memory and history the sites of bloody massacres in Ukraine where the genocide of Jews was carried out, which few people have known and heard about until now. They also did not know about the Righteous Gentiles who, living in a sea of hatred, indifference, and insensibility, did everything possible to help and save their compatriots who were outcasts in their homeland.

The books contain recollections of how, in the face of the terror and repression of the Nazis and their henchmen, they came to the Jews’ rescue, often risking their own lives and the lives of their loved ones; showed compassion and kindness; prevented Jewish pogroms; reported about impending executions; warned Jews who had fled from the ghetto and were wandering through villages, wondering which road to take; moved them to partisan groups and those few areas of Transnistria where the situation of the Jews was somewhat safer for a while; brought food to the ghetto and made false documents for them; hid Jews in their homes, etc., etc.

Perhaps for the first time, some witnesses recount the “good Germans” who were not hostile to the Jews but were even benevolent toward them on occasion. Not all Germans took part in acts of cruelty. There were many cases (and you can read about it in these books) when they, remaining true to the noble ideals of humanity, helped and saved the Jews.

Neither do the authors of these recollections sidestep the complex and painful questions of the cooperation between certain segments of Ukrainian society and the Nazis, collaboration, and anti-Jewish sentiments and actions of aggressive nationalists who wanted, as the noted Ukrainian historian Yaroslav Hrytsak has noted, “to see the future Ukrainian country Judenfrei, without Jews (Yaroslav Hrytsak, “Chy UPA brala uchast′ u pohromakh, a chy dopomahaly riatuvaty ievreїv?” (Did the UPA Take Part in Pogroms or Did It Help to Save Jews? Ukraїns′kyi zhurnal, no. 10, 2009).

The relations between the allied occupiers (Germans and Romanians in Transnistria), local Ukrainian Jews, and Jews who were deported to Ukraine from Bessarabia, Bukovyna, Romania, and other territories, and non-Jews are presented by witnesses much more fully and in a more complex fashion than they are reflected in official historiography or even in the memoirs that appeared prior to the glasnost era in Russia and abroad.

It is only recently that not just death (injustice, inhumanity, horror, and the brutality of criminals, antisemitic sentiments, acts of violence by collaborators, as well as the indifference of Gentiles who, though they did not kill them, neither did they help them during the Holocaust), but life—humane acts and the hidden altruism of Jews, the prohibition on assisting and supporting one another with a high degree of risk, and the struggle for survival in enemy-occupied territory, which were examples of active resistance to Nazi policies, albeit without the use of weapons—and the war, too (ghetto uprisings and participation in the partisan struggle)—have come to our attention thanks, above all, to the testimonies of people who managed to survive and whose truth we are able to hear and read in these books. Accounts of horror and accounts of assistance were integral aspects of that complex reality and refer to a detailed description of the European Jewish experience.

The books contain the recollections of different people who live far from each other today (in large and small cities, towns, villages, and countries, including Australia, Belarus, Germany, Israel, Russia, the United States, and Ukraine), but who were in the same place and at the same time during the war and the occupation. They convey a vibrant and truthful story, the way it was experienced and imprinted on memory. They convey to readers something that is very crucial and which is inaccessible by any other means; and how all of them in their own way recount the same historical event, that part of their fate that is mainly associated with persecution and genocide, with a period when death was the norm and life was a miracle. Here real facts are not distorted, as a rule, but the details, the specifics, the logic of events, accents, and digital data can often be different. This depends, among other things, on the person’s personality, upbringing, value system, intelligence, outlook, etc. Each one has a story. But what strikes us nevertheless is that similarities come to the fore in memory. It becomes collective memory, folk memory. The stories recounted by a survivor are his/her memory and interpretation of the events of a personal and devastating past. At the same time, they represent a collective experience; they recount shared memories of physical and emotional suffering and torment, of endless cruelty and violence, and the struggle for survival. These texts were not edited.

According to the testimonies of concentration camp and ghetto prisoners in Nazi captivity, they dreamed of surviving not only out of a sense of self-preservation, but also because they wanted to chronicle what they had experienced. They wanted their personal experience to prevent something like this from ever happening again.

But there was another reason: They sought to recount the tragic days they had experienced, to commit to memory every scrap of life, no matter how unendurable, no matter how painful these recollections, so as not to disappear into oblivion.

From the reminiscences of Yuliia Penziur-Veksler (b. 1936), whose childhood after her entire family was shot was spent in the small village of Tyrlivka, Vinnytsia oblast, “in attics, in ravines, in pits, in an abandoned chapel behind the village, among the bushes and graves of the rural cemetery":

“'The past is frozen in me. I do not part with it. Because I have my own Babyn Yar. It was in my childhood; it will remain with me for the rest of my days. I leave it to my children to remember.… All I can do to preserve the memory of my lost relatives is to tell them about them, repeat their names in my children and grandchildren. My family, my relatives—this is the biography of the entire Jewish people. All this is very tragic because it went through war, genocide, and antisemitism. This should be remembered: ‘This is our biography’" (Leben und Tod in der Epoche des Holocaust in der Ukraine, pp. 413–16).

Lidiia Slipchenko (b. 1915), miraculously saved in Odesa and neighboring villages, ends her recollection “The Truth about the Improbable,” with these words:: “Sometimes I think that what I have described here as the ‘blood of my heart’ may seem long-known and boring to the reader. But then I reassure myself that there are themes in the history of the country and the people which will always remain unforgettable. We must return to them again and again if only to ensure that what happened will never happen again. After all, people always return to the topic of the war, during which millions of people died on the battlefields. In my case, there was no battle in the full sense of the word; rather, it was a massacre, something terrible and humiliating at one and the same time, which is forever imprinted on my memory and imprinted on my soul. It seems to me that if I express this, convey it to people, I will partially relieve the terrible burden of memories that I have carried for so many years and which, perhaps, I will rid myself of a little by the end of my life” (Leben und Tod in der Epoche des Holocaust in der Ukraine, pp. 809–10; Life in the Shadow of Death, vol. 1, pp. 96–97).

Yosef Retseptor (b. 1904), recounting the tragedy in Lutsk, where the Nazis and their collaborators shot his family along with 17,500 Jews between 20 and 23 August 1942, noted: “Who will put their terrible tragedy into words?... Who will remind the world of the great injustice and losses that we Jews suffered to satisfy the monster of Hitlerite Germany? Who will remind the world that not just the German executioners and their helpers were responsible for our great catastrophe—they carried out the murders—but also heads of states and religious figures who knew that innocent people were dying and did not raise their voices in protest, which could have reduced the number of victims. And who will remind the world that deep-rooted and still calmly perceived antisemitism, hatred of Jews, has led to pogroms and mass murder for generations? As long as we live, it shall remain our sacred duty. We must pass this duty on to our children, so that this memory is passed down from generation to generation. This would be the greatest wish of our martyrs at the moment when they shed their blood and lost their lives” (Leben und Tod in der Epoche des Holocaust in der Ukraine, pp. 124–25; Life in the Shadow of Death, vol. 1, pp. 96–97).

They want to leave behind testimony, speaking on behalf of those who remained mute victims. The desire to preserve the memory of the past is also an act of resistance to modern antisemites, neo-Nazis, and Holocaust revisionists, who, in denying and distorting the memory of the victims of the Catastrophe, seek to ignore the irrefutable and proven fact of its existence.

The importance and value of these memories is growing with every passing day. After all, soon we will no longer be able to communicate with living witnesses of that time, whose knowledge can help fill the gaps that still exist in recent history. And where there is a wasteland in the place of facts, thought freezes there and loopholes open for impure speculations and conjectures, for distortion and falsification. Unfortunately, there is a pattern: The fewer eyewitnesses and victims of the Holocaust the more its deniers crop up.

The testimonies of the victims of Nazism (in a situation where the traces of crimes and witnesses have been destroyed, there are no true documentary materials, and many more archival collections related to the Catastrophe have been closed) are an irreplaceable source. No archives, films, or history books can convey their harrowing experiences as effectively as their personal stories.

President Shimon Peres of Israel noted that is precisely their heartbreaking memories and stories which guarantee that no one will be able to distort history and deny the truth about the Catastrophe. The voices of survivors keep alive the memory of the victims of the Holocaust and will not allow you to erase the dark pages of the past from history. The voices of Holocaust survivors unite our collective minds. It is thanks to them that we remember the innocent victims. Their stories help us remember. And never forget. Not today, not in the future.

Such information is particularly important in light of the danger posed by the ever-increasing quantity of neo-Nazi and antisemitic literature aimed at downplaying the Catastrophe and even denying it completely; at whitewashing National Socialism and antisemitism of their guilt and responsibility for the genocide of the Jewish people.

In order to dispel distrust of the Holocaust, which is a manifestation and strengthening of antisemitism and related prejudice and an insult to the victims and their descendants, we need strong evidence and, above all, the testimonies and recollections of eyewitnesses and participants in the events that took place. Elena Shcherbova (b. 1930), who miraculously survived the hell of the ghetto and Drobytsky Yar (Kharkiv), notes: ‘Only eyewitnesses can know and say what really happened. A normal person cannot even imagine how far human brutality, whose name is fascism, can reach” (Leben und Tod in der Epoche des Holocaust in der Ukraine, p. 1028).

Although these books are written by Jews, they are not just for Jewish readers. These recollections are a direct challenge to all racial, religious, and ethnic hatred, past and present, showing what happens when human rights are violated and no one raises a voice in their defense. The books do not call for revenge and hatred. Elie Wiesel noted that hatred is humiliating, and vengeance is shameful, and that they are sinful in themselves. They (memories and memory) warn and preach hope. Otherwise, perhaps, there would not be these books which, we hope, will be embedded in the general edifice of human history.

Today, when a wave of xenophobia and antisemitism, along with violence and hatred, especially in the West, has risen sharply, when, according to German Chancellor Angela Merkel, antisemitic and nationalistic sentiments are once again gaining in popularity and becoming commonplace, when the “Holocaust is fading from memory” (The New York Times) or denied, and fewer and fewer witnesses of the tragic past remain, preserving the memory of the Holocaust, a truthful examination of its history and its important lessons for humanity and its transmission to new generations are more important than ever—and urgent.

Dr. Borys Zabarko (b. 1935) is an Honored Worker of Science and Technology and winner of the National Academy of Ukraine Prize and a B’nai B’rith Europe Prize (“In recognition of his efforts to immortalize the tragic memory of the Holocaust.”) He is the author of more than 250 books and articles published in Austria, the UK, Hungary, Germany, Israel, Russia, the U.S., and Ukraine.

Werner Müller (b. 1936) and Margret Müller (b. 1939) are volunteers at a German charitable organization that helps former prisoners of Nazi concentration camps and ghettos. In 1994 they began corresponding with Polish concentration camp survivors, and in 1996 they began meeting with Jewish survivors of concentration camps and ghettos in Poland, Belarus, and Ukraine. Werner Müller is the author of the book Aus dem Feuer gerissen: Die Geschichte des Pjotr Ruwinowitsch Rabzewitsch aus den Ghetto Pinsk (Snatched from the Fire: The Story of Piotr Ruvinovich Rabtsevich from the Pinsk Ghetto, 2001) and the article “Sonderführer Günter Krüll,” in Wolfram Wette, ed., Zivilcourage (2004).

Originally appeared in Russian @ vaadua.org

Translated from the Russian by Marta D. Olynyk.

Edited by Peter Bejger.

NOTE: UJE does not necessarily endorse opinions expressed in articles and other materials published on its website and social media pages. Such materials are posted to promote discussion related to Ukrainian-Jewish interactions and relations. The website and social media pages will be places of information that reflect varied viewpoints.