Bringing back polyphony. A review of books short-listed for the Encounter prize in 2025

On 3 October, the fifth edition of Encounter: The Ukrainian-Jewish Literary Prize will announce its winner — a book of fiction that contributes to Ukrainian-Jewish dialogue. In the meantime, we will review the short-listed submissions, which include texts by contemporary writers and 20th-century authors. Written in Ukrainian or Yiddish, these books offer a Jewish perspective on the 20th century, revealing how Ukrainians and Jews saw each other and restoring to Ukraine its inherent multiculturalism.

Isaac Leib Peretz, Hasidic

– translated from Yiddish by Oleksandra Uralova and Sofiia Korn. Kyiv, Dukh i Litera, 2025, 320 p.

While the figure of Sholem Aleichem is recognizable in the Ukrainian cultural context, and his Tevye the Dairyman appears under various covers on the book market, the other two fathers of Yiddish literature, Mendele Mocher Sforim and Isaac Leib Peretz, were not so lucky.

Peretz's stories are set in the world of the shtetl with its folklore and tragicomic perception of the world. These stories offer insight into what happened in the Pale of Settlement on Ukrainian lands a century ago. Talne, Berdychiv and its suburbs, Vasylkiv… All these towns are filled with Jewish voices, complementing our contour maps of memory. Imbued with a mixture of Jewish wisdom and wit, Peretz's stories are like parables — they do not sermonize but constantly reflect on life. These reflections involve a dialogue with Kabbalah, which the translators mark in the footnotes. For readers immersed in this context, Peretz opens up space for dialogue. For the wider public, these stories are more like folklore: they masquerade as folk wisdom, and one can imagine how readers retold them, omitting layers of Hasidic intertext.

At the same time, a bizarre thing emerges in these texts. For the first time in their lives, the characters begin to do something atypical for their milieu — they think about ordinary things and ask questions about life. This makes them appear crazy in the eyes of society. However, poetry and everyday wisdom sprout in their very way of thinking. The book is replete with specific Jewish holidays, words, and rituals, which require plentiful footnotes.

Peretz's stories were once translated by Mykola Zerov. The current publication presents a new translation made by Oleksandra Uralova and Sofiia Korn.

Sonya Kapinus, White Rabbits

– Publishing House ORLANDO, 2025, 242 p.

White Rabbits is the author's debut novel, which depicts pre-revolutionary life with its romantic but disturbing flair, and Jewish Odesa.

The novel is written in the form of letters from the main character, Sonya. Currently, the narrator is married for the second time, expecting a child, and living in Athens. The letters she writes to a friend reveal not so much her present as her past. For Sonya, they become a way to hide in the shell of her earlier life — enter the vanished world of old Odesa, where she lives happily with her parents and is deeply in love with a doctor 17 years her senior. The period is marked by anti-Jewish pogroms, when the usual world begins to fall apart. The narrator experiences one shock after another. When the pogroms begin, Sonya finds herself in Rome, studying drawing. She is not very much affected by these atrocities, being more preoccupied with her suitors and learning the news from her country indirectly. (After all, many young girls who were taken out of Ukraine during a full-scale invasion are more interested in their here and now, new friends, and adaptation to the new world than in the constant consumption of disturbing news.) But Sonya sees the consequences of the pogroms with her own eyes. The further she is separated from her comfortable childhood, the more upheavals await her.

The novel is stylized as letters written in the early 20th century, potentially evoking echoes of Russian literature of the time. After all, Sonya's writing suggests that she speaks Russian (apparently, a wealthy Jewish lady from Odesa would have spoken Russian). On multiple occasions, she also mentions Tolstoy and Dostoevsky as her usual reading material.

Centuries of Presence. Edited by Khrystyna Semeryn

The Jewish World in Ukrainian Short Prose of the 1880s–1930s

– Kyiv, Dukh i Litera, 2024, 680 p.

Jews have always been present as characters in Ukrainian literature, but their portrayal has changed over time. Perhaps the most recognizable image of a Jew in literature is that of an innkeeper or a moneylender, whom other characters constantly have a grudge against. Now, the anthology compiled by Khrystyna Semeryn shows other dimensions of Jewish life in Ukrainian texts of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The anthology brings together texts that capture the lost world of Jews, who comprised a good third of the population in many towns. We seem to have already done our share of longing for the lost world of the Austro-Hungarian "golden age," so now may be a good time to see another layer of our own vanished world.

Since these texts refer to the same period as Peretz's stories, it becomes clear how differently the Jewish world was viewed from within and from without. For Ukrainian authors, the shtetl is as exotic as the Hutsul or Crimean Tatar world. While Peretz's stories are peppered with quotations from sacred books and references to rituals and holidays, Ukrainian texts are much more economical in their treatment of Jewish rituals.

This anthology is valuable because it shows Ukrainian curiosity about the Jewish world. Unlike the imperial approach, this is not about equalizing cultures. Instead, it is a cautious curiosity about others living side by side with you. It is about compassion and wonder. Among the better-known texts are those penned by Ivan Franko, who depicted Jews in his Boryslav stories and his classic novel Crossroads. There is also "He is coming!" by Mykhailo Kotsiubynsky, a textbook Ukrainian story about the horrors of anti-Jewish pogroms. Next to them are beautiful texts by Modest Levytsky, an author little known to Ukrainian readers who was friends with the Kosach family and Yevhen Chykalenko. A doctor by profession, he had the opportunity to see the closed Jewish life and depicted it in his prose.

The anthology reveals Jewish life through the lens of classical writers, while also introducing readers to Ukrainian authors with whom they may not be familiar.

Eli Schechtman, Ringen oyf der Neshome (Rings on the Soul)

– translated by Alma Shin. Lviv: Apriori, 2023, 448 p.

Eli Shechtman was born at the beginning of the 20th century in what is now Zhytomyr Oblast. He survived the Holocaust and Stalin's purges to describe in his books the world of the now-vanished shtetl life and the hardships the Jews endured in the 20th century.

The novel is structured as the memoirs of an old writer, recounting his life from childhood in Podillia to his emigration to Israel. The narrative is not exactly linear. Instead, the author peels off memories from himself layer by layer. His Jewish protagonist observes political changes — immense joy when the tsar is overthrown; the hope that the wife of Volodymyr Vynnychenko, head of the UNR Directory, is Jewish (a comforting signal for the Jewish people), and the beginning of antisemitism.

The book is both interesting and useful in modern context amid a growing interest in reviewing 20th-century history through the prism of family stories and without the imperial overtones. It was only after Russia's full-scale invasion began that we started seriously reconsidering the revolutionary beginning of the 20th century and peeling back the layers of propaganda from history textbooks. Therefore, it is our duty to hear the voices of "our others," for whom Ukraine was home. Without these fragments of history and without books about the Jewish experience of the 20th century in Ukraine, our vision of the past remains fragmented and muddied.

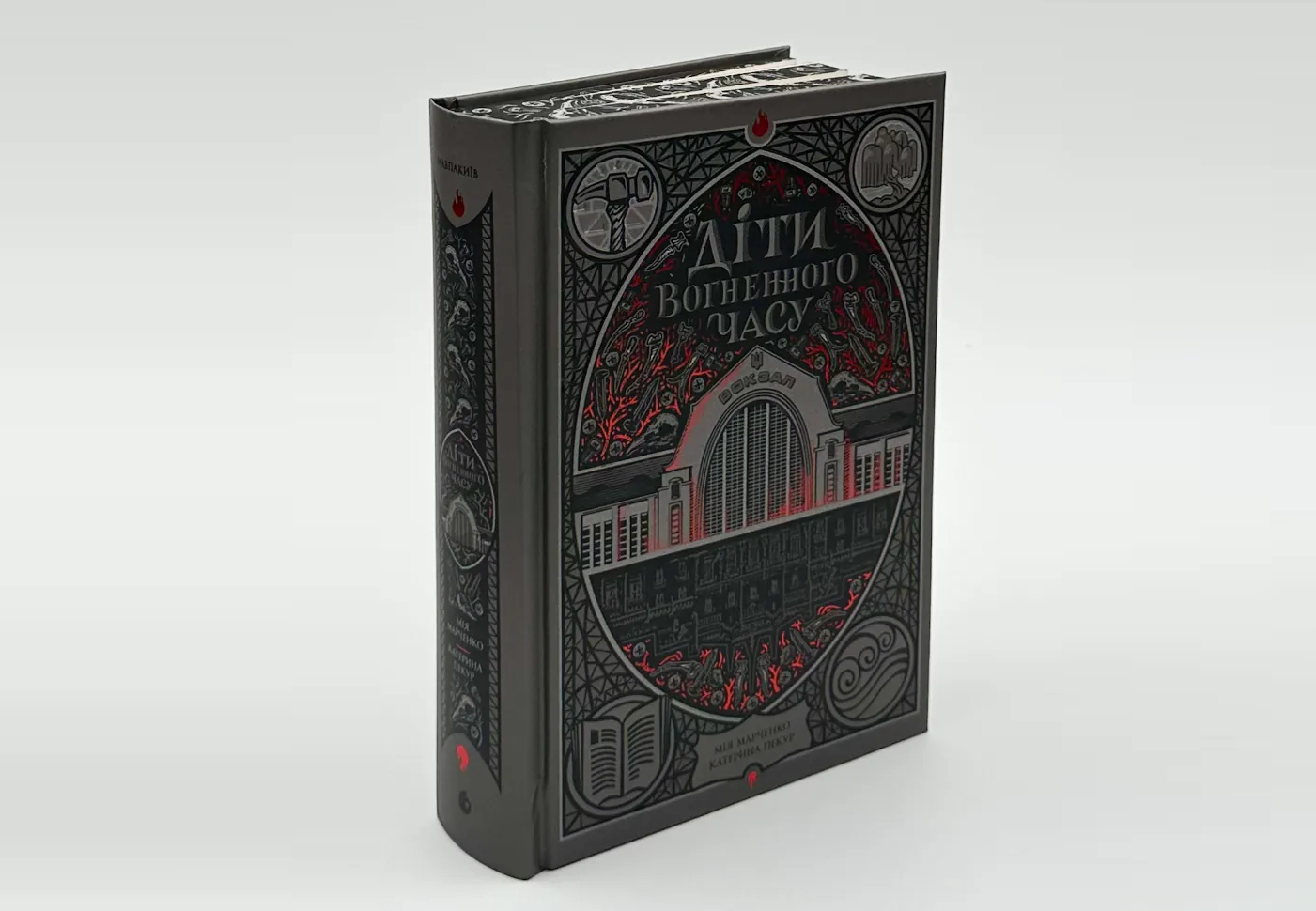

Mia Marchenko, Kateryna Pekur, Children of the Burning Time

– Kharkiv: Readberry, 2024, 640 p.

This book, a fantasy novel constructed in two planes, stands out from the other submissions as the one most deeply immersed in modernity. The historical reality is the beginning of Russia's full-scale invasion that drove thousands of people to the Kyiv train station in search of ways to escape the war. The fantasy plane is an eclectic, imaginary Kyiv inhabited by a diverse array of fantastic creatures. A city in which all historical layers have been mixed. We see representatives of different nationalities and professions, as well as creatures speaking languages from various decades and centuries.

Like another famous fantasy novel set in Kyiv, Lazarus by Svitlana Taratorina, Children of the Burning Time deals with a multinational Kyiv. This novel features Jews, thanks to whom the main characters receive their own golem, among other things. The golem maker, Avikhaya, turns out to be linked to the protagonist. As reimbursement for the golem, he asks her to recount a story, and the girl recalls the postcards lying around at home. In a bizarre coincidence, they contain an abbreviation composed of the names of Avikhaya's children. So no matter how much the girl tries to run away from him after this, she will have something that Avikhaya desires more than anything else.

As is repeatedly mentioned in the text, the elements of the fantasy world, Zavokzallia, exist as long as they are remembered. So as long as we continue looking at old photos of Jews, recalling where Yevbaz was, remembering the features of Jewish Podil, this Jewish world will exist. At least in the mysterious world of Zavokzallia.

Tetiana Petrenko

Tetiana Petrenko

Literary critic, editor at Chytomo's criticism department, radio host at Hromadske Radio, part-time researcher of mythologies and ancient literature, and contributor to the Bukmol, Litekcent, and Koridor portals. Personally responsible for all the love and death-related publications on the website.

Originally appeared in Ukrainian @Chytomo

Translated from the Ukrainian by Vasyl Starko.

This material is part of a special project supported by Encounter: The Ukrainian-Jewish Literary Prize. The prize is sponsored by the Ukrainian Jewish Encounter (UJE), a Canadian charitable non-profit organization, with the support of the NGO "Publishers Forum." UJE was founded in 2008 to strengthen and deepen relations between Ukrainians and Jews.