Canada’s Artistic Odd Couple: William Kurelek and Avraam Isaacs

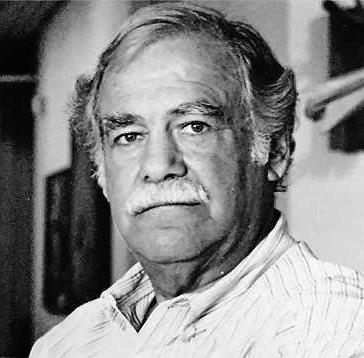

Interactions between Ukrainians and Jews over the centuries have been extremely complex and fraught with considerable tensions. At the same time, there have also been many instances of strong personal friendships and cooperation between Ukrainians and Jews, which often get overlooked by historians of both communities. One such example is the remarkably successful and enduring partnership formed by the artist William Kurelek (1927-77), and the art dealer Avraam Isaacs (b. 1926) – a seemingly unlikely pairing of very different personalities who nevertheless developed a relationship that transcended not only their ethnic and religious backgrounds, but their wildly dissimilar world views.

Although both were natives of the Canadian West, their lives first intersected after each had permanently settled, almost two decades apart, in Toronto. Whereas Av was born into a North End Winnipeg Jewish family that had emigrated from Eastern Europe, William was born in a rural Alberta Ukrainian settlement to parents with Bukovinian roots, his father having come to Canada as young man in 1923. Interestingly, while Kurelek’s family moved to Stonewall, Manitoba when he was a child of seven and he later attended the University of Manitoba, Isaacs moved with his parents to Ontario when he was a fourteen year-old, after which he went on to complete a degree in political science and economics at the University of Toronto.

The first encounter of the two men was brought about by the flourishing framing business and modest art gallery that Isaacs had created in the mid-fifties on Bay Street, though there are slightly different accounts as to the details of how their working relationship got started. What is undisputed is that Kurelek began making gilded frames for Isaacs on a part-time basis in late 1959 or early 1960, and this eventually evolved into a full-time job that supported William and his growing family while he attempted to establish himself as a full-time artist. Another thing which is clear is that Av immediately recognized Will’s unique talent as a painter, notwithstanding the fact that Kurelek’s artistic vision and sense of mission were seemingly diametrically opposed to those upon which Isaacs already had begun to build his reputation. By March 1960 Av had given Will his first solo show, an exhibit featuring an array of some twenty sketches and paintings done in the 1940s-1950s in the distinctively representational yet highly symbolic style, for which Kurelek was to become famous. The opening drew the largest crowd that Isaacs had hitherto hosted in the four-year history of his gallery, and it not only helped to launch Kurelek on his career as an artist, but also in some ways set the tone for their unusual friendship and fruitful collaboration, which endured until the death of the latter seventeen years later.

What was memorable about the event was that it drew a curious mix of people, ranging from the bohemian types and urbane collectors that typically frequented Isaacs’ shows, to Kurelek’s peasant-stock parents and circle of conventional friends who were participating for the first time in Toronto’s burgeoning contemporary art scene. It was Av’s genial nature and his ability to see beyond glaring differences that likely played a key role in making his partnership with Bill a success, just as it was Kurelek’s determination to be a professional artist and his proselytizing zeal that enabled him to find common cause with an astute businessman and gifted promoter of Canadian art – who also happened to have a keen sense of good taste and auspicious timing. That the 1960s were a vibrant decade when questions of ethnicity were emerging from the shadows thanks to the debate over the nature of Canadian identity undoubtedly helped to bring about the unusual “mixed marriage” of minds that bonded the two men. For, despite their divergent opinions on many issues, they trusted and respected each other implicitly, while at the same time sharing some core values that allowed them to brush aside the occasional stresses and strains that inevitably arise in every long-term relationship: a deep love for Canada, unshakable confidence in their own convictions, and an abiding belief in the importance and transformative power of art.

Thus, although Kurelek was a fiercely devout Catholic with staunchly conservative views that were in many respects totally out of step with the times, whereas Isaacs was a thoroughly secular and unpretentious sophisticate who blossomed in the freewheeling atmosphere of the Sixties, their alliance prospered to the benefit of both. What Isaacs brought to the table was his iconoclastic appreciation of quality and his extensive network of friends, including many patrons of the arts in the Jewish community who became fans and collectors of Kurelek’s works. What Kurelek brought to the table, besides his unique talent as a painter, was his incredible work ethic and his growing circle of Ukrainian admirers who supported his artistic efforts and nourished his sense of belonging to a wider community. Along with the solace that Kurelek found in his conversion to Roman Catholicism, he was also helped by Isaacs to gradually overcome his profound feelings of loneliness and doubt, which had led to the serious depression that he suffered as an art student in England and underlay the social awkwardness that affected him his entire life. Fortunately, Canadian culture was immeasurably enriched in the process by which Isaacs’ and Kurelek’s names became inextricably linked, something for which all lovers of art can be grateful.

That both men came from humble East European origins and shared strong feelings about social injustice, was likely part of the reason why they were able to set aside their ideological, spiritual, aesthetic and other incongruities, which, however pronounced, never became serious points of contention between them. But what probably especially drew them together was their awareness of being from the margins of mainstream postwar Canadian society and their broadly humanistic values, as each had roots in communities that had experienced more than their fair shares of discrimination, persecution and outright horrors.

Although Kurelek continues to be strongly identified with his large catalogue of paintings devoted to Ukrainian Canadian themes, he was also eager to reach out to other minorities in his own unique way, using his art to tell stories with which he could personally connect even if they were far outside of the world that he had inhabited. Among several examples of this sensibility and approach was his acceptance of a commission that became the basis of the series “Jewish Life in Canada,” produced on the initiative of Abe Schwartz and realized in a book-form collaboration (appropriately published in Alberta by Mel Hurtig) with the late historian, journalist, and Jewish community activist, Abraham Arnold. By all accounts, Abraham, like Av, had a larger-than-life personality that was very different from Kurelek’s, who in turn had an understanding of Jewish-Christian relations that was somewhat controversially expressed in his epic series, “The Passion of Christ.” However, whatever their differences, they obviously fulfilled their shared objective, producing a heartfelt work that became yet another bridge between the Ukrainian and Jewish communities in Canada. But that is the beginning of another story for another time in the on-going dialogue and continuing evolution of Jewish-Ukrainian relations.

By Jars Balan