Celan speaks to contemporary Germans, teaches them about responsibility, morality, and offers them a different take on their history: Petro Rykhlo

The continuation of a conversation about Paul Celan, the distinguished German-language poet who was born in Chernivtsi.

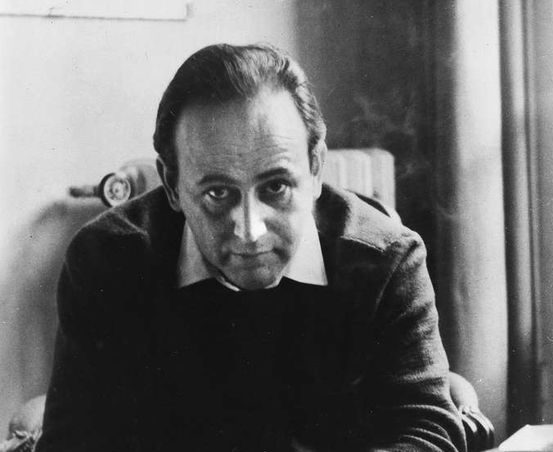

Our guest today is Petro Rykhlo, translator, literary historian, Doctor of Philology, professor at Yurii Fedkovych Chernivtsi National University, and co-founder of the Meridian Poetry Festival.

Vasyl Shandro: Was Paul Celan read clandestinely?

Petro Rykhlo: His texts were not banned; they were not outlawed. However, for a certain period of time they simply did not exist. In 1978 the journal Vsesvit published a collection of Celan’s poetry, which was compiled by the distinguished Ukrainian poets and translators Mykola Bazhan, Leonid Cherevatenko, Moisei Fishbein, and Marko Bilorusets. This publication sparked my interest in Celan; a local-patriotic note played a role here to some extent. I thought it was incredible that a world-famous poet had been born in my city. I began to follow his creativity very closely, to collect everything that I could learn about him.

Later I published a few small collections of his poems; I selected them from his various books of poetry. Because he is a very complex poet, a poem torn from its context stands isolated amidst other random poems. It loses its roots. I realized that Celan must be translated systematically, collection after collection. I set myself this goal in 2007. I decided that by the centenary of the poet’s birth, I would translate all ten volumes of his lyric poetry. Today I can declare that this publication has been completed. I doubt that every European country has the complete works of Celan like Ukraine does.

Vasyl Shandro: Is Paul Celan part of Germany’s literary canon? Who is he and what does his poetry mean to the German-language reader and literature?

Petro Rykhlo: In the German literary canon, Celan is not only present—he dominates it. He is regarded as the most distinguished postwar lyric poet in the German language. In terms of the development of the German language, he achieved what no other poet did in his time: a revision of the German language. During the twelve years of Nazi rule, the German language was terribly distorted and sullied. Celan took it upon himself to cleanse it.

The German philosopher Theodor Adorno famously said: “To write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric.” Celan took this as a personal challenge, proving that it is possible to write poems not only after Auschwitz but about Auschwitz. The Holocaust became a leading theme of his work. I think that no other poet has revealed more profoundly this terrible tragedy of the Jewish people and the terrible guilt of the German people. This was not just Hitler’s fault; at the time, he was supported by the broad masses. Even today, every German feels his/her historical responsibility for Hitler, for Nazism. Celan speaks to contemporary Germans and teaches them about responsibility, morality, and offers them a different take on their history.

He introduced an immense number of neologisms into the German language; he was very much a poet who created new words. These words have entered the German language. When a poet presents a people with new words and new expressions that later enter the public domain, this is a great achievement.

Vasyl Shandro: How important for us are Celan’s texts about the Нolocaust in the context of reinterpreting the tragedies of the Holodomor, the twentieth-century genocide?

Petro Rykhlo: Through his work, Celan offered a certain example of how to approach such catastrophes caused by political regimes. He speaks about the tragedy of his Jewish people as an ethnic Jew and offers an example of how to talk about our great catastrophe, the great tragedy of the Holodomor, but it is our poets who should say this. No Frenchman, Italian, or Spaniard will say this; this must be articulated by a Ukrainian poet. There are distinguished works on this topic in our country, but, obviously, this theme has not received such worldwide publicity. I hope that these times are still ahead. Obviously, some Ukrainian poets and writers working on this theme will appear, and they will treat it on as large a scale as Celan did for the Jewish people.

Vasyl Shandro: Were there any large-scale events outside of Ukraine this year [2020]?

Petro Rykhlo: All sorts of events were planned: international conferences, symposiums, exhibitions. In Germany, many books devoted to Celan were published. There is a monument to Celan in Chernivtsi, a street named after Celan, and a memorial plaque on the house where he was born. This year our oblast library, named after Mykhailo Ivasiuk, published a Ukrainian bibliography of Celan’s works. This is quite a solid book, featuring all the titles that have come out in our country, in Ukraine.

Equal efforts are being made in this regard in German-speaking countries. I was invited to a soirée hosted at the home of President Frank-Walter Steinmeier of the Federal Republic of Germany. But because of the pandemic, this event was moved to an online format. I was also invited to conferences in Romania, Hungary, and Germany.

In this regard, Ukraine is not far behind. Our Meridian Czernowitz Festival honors Celan every year. The very name of this festival, “Meridian,” is the founding notion of Celan’s poetry. “Meridian” is a symbol of his poetics, a symbol of dialogue. It is that invisible but earthly line that unites many key and iconic locations, cultural events, and historical actions. The festival is attended by poets from abroad, but this Celan accent is always present. For example, a series of lectures about Celan was just held, in which five Ukrainian authors and five German authors took part. All the lectures were published on the Internet; they can be accessed here.

Vasyl Shandro: When we talk about multicultural Celan, is this about the conflict between these cultures or coexistence?

Petro Rykhlo: Already during the Habsburg period, Chernivtsi [Czernowitz] was considered the Babylon of Eastern Europe because many languages, cultures, and religions were interwoven here. Perhaps what is most precious is that all these cultures existed peacefully. They were tolerant toward one another. They truly enriched and nourished each other. Celan would not have become Celan had he not absorbed all these streams from various cultures. In his poems, there are many references to the ancient stages of German culture, all the way to The Song of the Nibelungs. He translated from many languages; he also lived in these cultures.

Listen to the audio file for the complete conversation.

This program is created with the support of Ukrainian Jewish Encounter (UJE), a Canadian charitable non-profit organization.

Originally appeared in Ukrainian (Hromadske Radio podcast) here.

Translated from the Ukrainian by Marta D. Olynyk.

Edited by Peter Bejger.