Dave Tarras, the Ukrainian-born man who became known as “the Benny Goodman of klezmer”

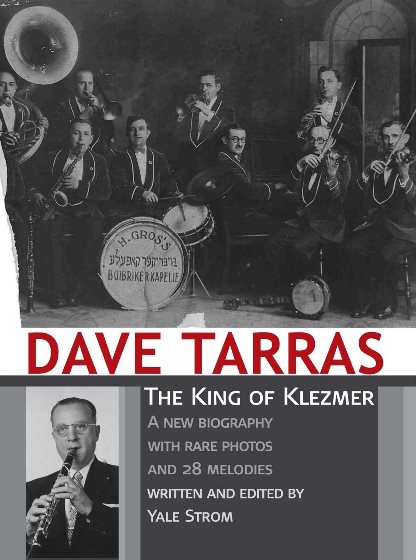

Dave Tarras: The King of Klezmer by Yale Strom chronicles the life and work of a Ukrainian-born man who became known as “The Benny Goodman of Klezmer.”

Dave Tarras: The King of Klezmer by Yale Strom chronicles the life and work of a Ukrainian-born man who became known as “The Benny Goodman of Klezmer.”

He was the individual most responsible for the development of a uniquely American style of Jewish klezmer music. From 1925 until his death in 1989, Dave Tarras set the standard. Well-known jazz legends such as Charlie Parker and Miles Davis studied his technique.

Yale Strom is himself an accomplished klezmer musician and historian. He is credited as a pioneer in the revival of klezmer. Strom had already published several books on the genre when by happenstance he ran into a great-grandson of Dave Tarras in New York. That encounter inspired Strom to write a biography of the iconic musician.

The book contains many touching anecdotes by family members, musical colleagues and proteges. There is newly discovered biographical material, rare photos, the musical scores of 28 of Tarras’ original klezmer tunes arranged for violin and clarinet, a glossary of Yiddish terms, a bibliography, detailed footnotes and discography. Plus, a copy of a handwritten note by Tarras a few years before he passed away.

Dave Tarras was born Dave Tarasyuk in 1897 in Ternivka, a shtetl in what is now modern-day Ukraine, located about 200 miles south of Kyiv and 19 miles southwest of Uman, where Rebbe Nachman of Breslov is buried.

Tarras was a third-generation klezmer musician. He learned his craft from his father and played at weddings for Jews and non-Jews in and around Ternivka. He even played in the Czarist army up to World War One. That gig not only kept him out of the trenches, in the end it saved his life.

Then pogroms broke out, foreshadowing even worse devastation and horror to come with the Holocaust. Tarras managed to escape to the west with his wife and some family members. Sadly, many of his relatives were left behind. Those that survived endured much hardship, including deportation to Uzbekistan through Siberia and Kazakhstan. Life was hard for klezmer musicians in the USSR. And it was also often dangerous.

Meanwhile, Tarras and his wife arrived in America in 1920, and got a job working in his brother-in-law’s fur shop. At first he did not think he was good enough to make a living as a musician in America. But within three years he was supporting his growing family playing his clarinet. He would go on to become the most acclaimed klezmer [musician] in the United States.

During his career he made hundreds of recordings, on labels such as Columbia and RCA Victor. He frequently played for Yiddish theater, resorts, social clubs, vaudeville and movie theatres. And of course countless weddings and other Jewish communal events.

The emergence of a new technology called radio allowed Tarras and other klezmer to reach a broader audience. By the end of the 1920’s, Jewish radio programming and Yiddish music were airing on several major radio stations in the New York area.

During the harsh Depression years Tarras worked many different venues, including in resort hotels in the Catskill mountains. The area came to be known as the Borscht Belt because Klezmer and Yiddish swing were so popular there.

By the end of the 1930’s Dave Tarras had becoame known throughout the Yiddish theatre and klezmer world as the best and most reliable clarinetist.

When WWII broke out, he did another army stint. He was commissioned by the national guard of New York to lead its military band.

But the end of the war brought with it the end of the big band era, and the beginning of a new American music scene.

Despite that, Tarras remained one of the few musicians to still record and play actively in the niche he had carved out for himself. This included gigs in the American Jewish community and as a session musician, recording, radio, and teaching music.

His audience was dwindling, however. The trauma of the Holocaust turned survivors and their descendants away from the painful memories and associations of their east European roots. With the birth of the new State of Israel in 1948, American Jews still in touch with their roots began to identify with a more modern Israeli culture.

But in the 1970’s Dave Tarras was “rediscovered” by musicians and researchers Andy Statman and Walter Zev Feldman. In 1978, they organized a tour featuring Tarras and other klezmorim and Yiddish singers. The project also produced a studio recording titled “Music for the Traditional Jewish Wedding.” This would be Tarras’s last studio effort.

The tour was a huge hit with seniors who recalled the heyday of klezmer. But it also attracted a smaller crowd of young musicians who would form the nucleus of a revival of Yiddish culture.

In 1984, Dave Tarras was honored by the National Endowment of the Arts with a National Heritage Fellowship.

He died on Feb 12, 1989 in Oceanside, Nassau County, New York, leaving a daughter, a son, and seven grandchildren. His great-granddaughter Stephanie Tarras is now the keeper of the family klezmer legacy.

Dave Tarras influenced several generations of klezmer musicians, and will no doubt continue to influence generations to come.

Dave Tarras, The King of Klezmer by Yale Strom is available at Amazon and other booksellers.

The musical excerpts you heard were all recordings by Dave Tarras. Apologies for my Yiddish pronunciation.

We began and ended with Chusen Kala Mazel Tov, a traditional Jewish Wedding March.

Then, Zefki, ikh bin dayner sher — a couples set dance similar to a quadrille or square dance.

Galatas — Grandfather’s song.

Freilachs – another traditional Jewish dance…the word means happy and this song was titled Фрейлахс Весёлый.

A Pastukhl’s Kholem (A Shepherd’s Dream) — from his 1978 recording “Music for the Traditional Jewish Wedding.”

You can find the music of Dave Tarras on Amazon and iTunes.

Listen to the program here.

Ukrainian Jewish Heritage is brought to you by the Ukrainian Jewish Encounter (UJE), a privately funded multinational organization whose goal is to promote mutual understanding between Ukrainians and Jews. Transcripts and audio files of this and earlier broadcasts of Ukrainian Jewish Heritage are available at the UJE website and the Nash Holos website.