Debora Vogel: Bringing literature closer to the imagery of avant-garde art

History sometimes imposes itself on life so fatally that even the most correct and worthy choices are disastrous, but it is impossible to know this in advance. "It's good to be alone; it's delicious to be not just alone but forsaken, hopelessly abandoned to the abyss of neglect and homelessness. This is when you 'see' better," Debora Vogel wrote in a letter. She was a Lviv-based Jewish writer, art critic, and scholar, considered one of the most educated women in Galicia in the 1930s. However desirable it may be in times of relative peace, loneliness often becomes a curse during upheavals when the tectonic plates of history break and diverge, forming dangerous cracks in between. Vogel, who, by virtue of her character, would have never embraced any grand ideology or joined a political force, fell into one of these cracks when the Catastrophe came. And she also fell into oblivion. More than an exceptional writer and thinker, she is a mirror into which one must look to see the memory of the reality that is relevant to our Ukrainian culture today. Vogel left something for us in this interior; we must read it.

The House on Lisna Street

When the Polish poet Jerzy Ficowski arrived in Soviet-ruled Lviv in 1965, he did not come to read poems or perform on stage. His incognito visit aimed to explore one apartment in a house on Lisna Street on the picturesque slope of Castle Hill. He knew he would not find its pre-war residents, the Barenblüths, there. Szulim, an engineer, and his wife Debora née Vogel were crushed by the terrible Shoah, like a hundred thousand Lviv Jews and millions of European Jews. Even before the war, Ficowski was fascinated with the prose of Bruno Schulz, a phenomenal writer from Drohobych. He even wrote Schulz a letter in the tragic year of 1942, when Schulz was killed in the Drohobych ghetto. The letter was doomed to go undelivered. After the war, when Schulz was no longer there, Ficowski set about reconstructing the legacy of his beloved author, putting it together piece by piece like a mosaic. Many pieces were missing, devoured by the war, but he still sought out anything Schulz had written. The most important things here were his letters. Scattered across dozens of cities and places where Schulz's addressees lived, they had the best chance of surviving.

While studying Schulz's biography, Ficowski regularly encountered the name Debora Vogel, simply Debora or Dozia, as her relatives called her and as she signed her letters. Everything indicated that Bruno and Debora shared an unusual, intimate relationship full of sensual and intellectual tension. All that had to be done was to find written evidence, i.e., letters. Thus, Ficowski came to Lviv searching for Vogel as a key to Schulz — no less, no more — and left with nothing.

In the freshly painted interior of the Barenblüths' former apartment, he found new tenants who were clueless about earlier residents. Only the housekeeper recalled that some "papers from different residents" were left over from the war, but "the previous year, they put things in order and burned all that paper and garbage." Schulz's letters sought by Ficowski probably went up in smoke with those papers, as did Debora's archive: her poems and prose, art criticism, and philosophical explorations.

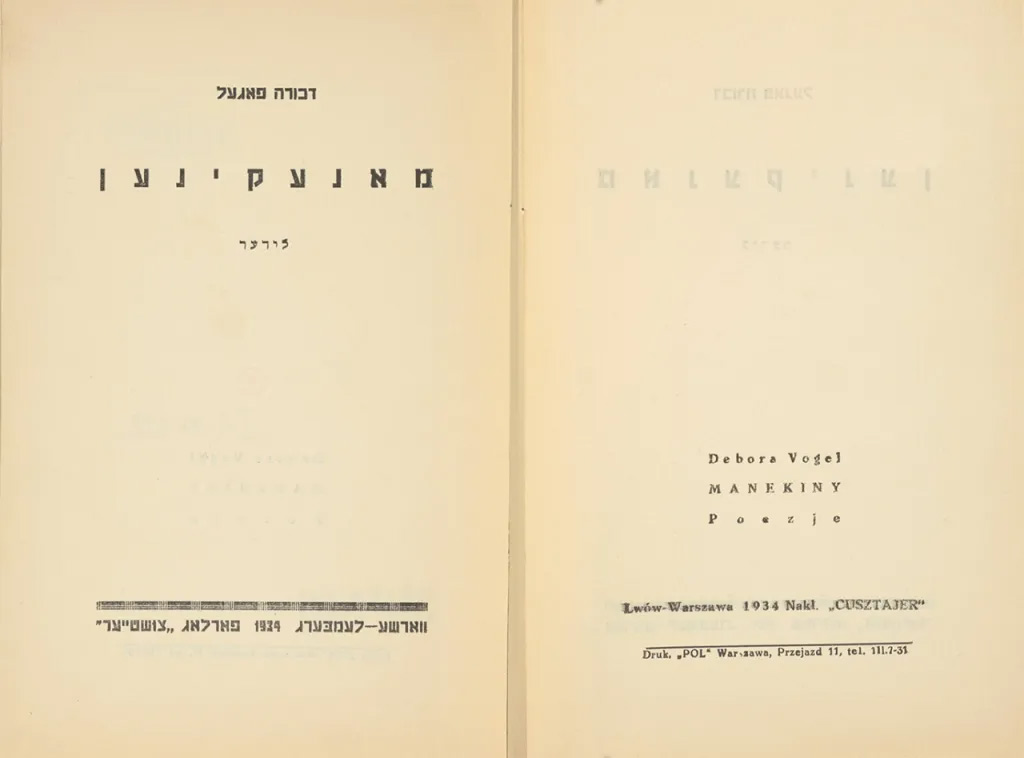

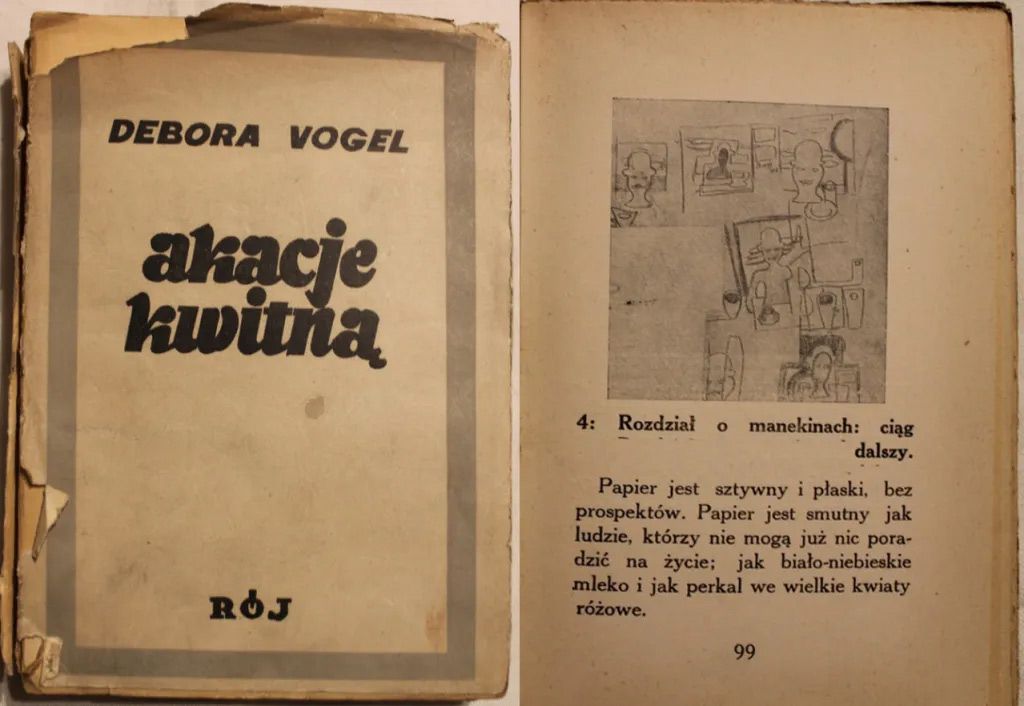

Vogel's surviving works were all written at 18 Lisna Street and published during her lifetime — two volumes of poetry, one collection of short experimental prose, and a few articles. No more, but no less.

The curse of shadow

Ficowski, who seemingly by chance and in passing saved Vogel's name from oblivion, did her a disservice simultaneously. The perspective he adopted on Vogel defined how she was viewed for decades — only as Schulz's "friend," "confidante," "muse," and "inspiration," whose own talent, however, did not elevate her to his level of brilliance. This curse of comparison, the curse of shadow, fueled by patriarchal prejudice, was felt even during their lifetime, which is why, wanting to emphasize Vogel's original talent, Schulz himself once wrote about her book of prose: "Some readers and even reviewers saw similarities between her book and my Cinnamon Shops. Such an observation is not indicative of particular insightfulness." But alas. Vogel continued to be mentioned only in the context of Schulz, her interlocutor, friend, and almost fiancé. This was the case until the 1990s when the first studies on Vogel and reprints of her works finally began to appear in Poland.

Schulz and Vogel met in 1930, during the interwar period, a relatively happy era for Europe and right on the line behind which the clouds of the imminent catastrophe began to gather. But so far, with the rumbling of a thunderstorm far away and only vague flashes lighting up on the horizon, entire continents of life separated them from the inevitable. I imagine the two of them walking together over the Znesinnia hills in Lviv, talking about topics beyond comprehension to ordinary minds. (After all, there is no need to imagine: their mutual friend, the writer Rachel Auerbach, described their walks as "true poetic-philosophical symposia.”)

They thought and wrote in unusual and strange ways, and their audience was only catching up or perhaps was just emerging. Both rowed the shaky boat of Jewishness, which could be (and was) overturned by every historical storm in these latitudes. No other kindred spirits seemed to be closer in the city and the whole world. And yet… He chose to write in Polish — the only language in interwar Poland that facilitated, rather than complicated, the writer's career. Moreover, he was a man. She was a woman who decided to write in Yiddish. For him, Jewishness was a domestic whim, an exotic exhibit, and a childhood dream. For her, it was an adult choice, self-dedication, and a mission.

As a woman, Jew, Yiddish author, and avant-garde artist, Vogel lived in conservative provincial Galicia, where even one of these factors was enough to significantly complicate a literary career. Thus, she found herself under five stifling covers, five ceilings that smothered her fame during her lifetime and after death.

Does Yiddish have a future? Really?

Like Schulz, Vogel came from a Polish-speaking, assimilated Jewish family. In contrast, her family was deeply aware of their Zionist roots. In the town of Burshtyn, where Vogel was born, there were long-standing Jewish scholarship and literature traditions. Still, the Vogel family stood out even against that background as particularly intelligent and educated. Vogel's great-grandfather Avrom Nissen Züss was a scholar and kabbalist in Lviv. Her uncle Marcus Ehrenpreis was the chief rabbi of Bulgaria and later of Sweden. Her father, Anselm, was a teacher, director of the Baron de Hirsch Trade School, and the guardian of the Jewish orphanage in Lviv's Pidzamche district after World War I. Debora's mother, Leia, taught at a craft school for girls in Burshtyn. It would not have been surprising if Debora had chosen Polish for writing, as it was spoken in the family daily. Alternatively, she could have chosen Hebrew, the language they read in and were proud of. Finally, Vogel knew German perfectly well after studying at a German gymnasium in Vienna during World War I. Yet she chose Yiddish, which her milieu did not know and despised.

For the Zionists, who set the goal of reviving the Jewish people and their ancient culture in the historical land of Eretz Israel, Yiddish was nothing more than a stigma of enslavement. The language was used by millions of Jews in Eastern Europe not only in everyday life but also in literature, which by the beginning of the 20th century produced such renowned classical figures as Mendele Moicher Sforim, Sholem Aleichem, and Yitskhok Leybush Peretz. Still, the Zionists considered Yiddish a humiliating mixture not worth being dragged into the future. Yiddish writers, whom we could call "populists" following the Ukrainian tradition, held the opposite opinion: for them, Yiddish was the only language that could describe Jewish reality, the restless world of Jewish shtetlach, markets, houses, and shops. Yiddish was indispensable. In 1908, Jewish writers and intellectuals gathered in Chernivtsi for the first conference on Yiddish to outline the future of this language, free it from the captivity of folklore and Hasidic tales, and introduce it into the circle of modern European cultures.

However, even this was not enough for the generation that came after World War I. It wanted to see Yiddish culture not just as modern but as ultramodern, avant-garde, futuristic, and cubist! The language of damp courtyards, bazaars, fairy tales, and incantations was to become the language of airplanes, radio, and bold artistic experiments. Yiddish avant-garde circles emerged in New York ("In zich"), Łódź ("Young Yiddish"), and Warsaw ("Di Chaliastre," i.e. the band). One also sprung up in Lviv, which would have been impossible without Vogel, an intellectual who believed in Yiddish as the language of the future.

"White Words"

That Vogel embraced Yiddish was a rather unexpected turn of events because she started, quite predictably, as a Polish-speaking Zionist. In her youth, she belonged to the popular left-wing Zionist organization "Young Guard" and wrote and published her first texts in Polish. Things changed when Vogel enrolled in the philosophy department at Lviv University in 1919. There, she met Rachel Auerbach, who would become her long-time colleague and friend. Auerbach grew up speaking Yiddish at home and convinced Vogel to write in mame loshn, i.e., her mother tongue. At first, Auerbach translated Vogel's texts from Polish, then Vogel did it herself, and later she wrote directly in Yiddish.

Galician Jewry was often considered too assimilated and "sleepy." Even the Yiddish spoken in Galicia was deemed inferior for being excessively Germanized. Something urgent had to be done about this. In the late 1920s, an active group of Yiddish writers decided to publish a literary magazine in Lviv. They called it Cusztajer (Gift), with Rachel Auerbach and Debora Vogel at its core.

It was an ultramodern, world-class magazine — a white frigate on the "sleepy" waters of Jewish Galicia. Vogel was finally able to write the way she wanted and about the topics she loved and knew well: avant-garde artistic explorations in the world; Cubism, Constructivism, and Surrealism; the works of her colleagues, Galician experimental artists (Bruno Schulz, Henryk Streng, and Otto Hahn); "white words" in poetry. What are these?

Debora Vogel dreamed of Yiddish becoming a dynamic, flexible, and urban language that would be ahead of its time instead of catching up with it.

She also dreamed of literature that would come close to the imagery of avant-garde art and words that could express a dynamic, stereometric world of "pure forms" instead of the burdensome material senses. "The tendency to free poetry from its literary character and consider it a construction made from verbal material is a requirement for modern poetry," she wrote.

The "white words" Vogel reflects on are seemingly banal, hackneyed constructions that are, nevertheless, key to understanding the mechanics of the world. The literary character she criticizes is not only aesthetic snobbery but also the inability to perceive a deep algorithm (or simply a rhythm) of being that hides beneath the "ordinary," repetitive, and mundane.

This is what Vogel's poetry and prose are like. In the white or gray quadrangles of days, shop and house windows flicker, and scraps of everyday conversations are heard. One familiar form — flat, as if cut out of cardboard or foil — replaces another, "and nothing comes / the sticky growth has been seen so many times / we've had so many paper days in white." However, this superficial boredom and statism and the repetitive gestures and structures of a big city conceal a hook that can be grasped to "unfasten" the visible and see its underpinnings.

Vogel's poems, like her "montages" (a genre of short experimental prose sketches she invented), are among the best things that happened in the Eastern European literary avant-garde of the 20th century.

Vogel is holistic and consistent in her writings and views on art, her vision of the future of Jewish culture, and her philosophy. She is original and special.

This was her happiness but also her drama. In one of the few surviving letters to Schulz, she describes her soirée in Lviv in 1938 with bitterness: "For whom are we writing in Yiddish? Those who came grasped the essence, but their lack of language proficiency greatly hindered them. None of the Yiddish poets came." Indeed, those who knew Yiddish did not understand Vogel's aesthetics and vice versa. Such was the situation of the Yiddish avant-garde in Galicia. Vogel's friend Rachel Auerbach got tired of banging her head against this wall and moved to Warsaw in 1933. In contrast, Vogel decided to remain with her city until the end.

Ghetto

Her marriage with Schulz never took place. Debora's mother stood in its way as she sought to "organize" the life of her overly creative daughter, who was detached from practical matters. Schulz was not a good partner for a well-established and peaceful life. Vogel married the stately engineer Szulim Barenblüth. It was not so much a marriage of convenience as one of "order." Soon, their son Anzelm was born.

Meanwhile, clouds were gathering on the horizon, and the harbingers of disaster were becoming more and more apparent. We know from Vogel's letters that she was preparing new collections of poetry and prose for publication on the eve of World War II. All of them most likely ended up among the burned "papers" in the basement of her house. In September 1939, after Hitler invaded Poland and Eastern Galicia was occupied by the Soviets, Polish artists and writers began to arrive in Lviv in the hope of escaping from the Nazis. Vogel and her husband accommodated them and provided the necessities. The poet Aleksander Wat long remembered the coat that Vogel gave him as it saved him from the cold in the Stalinist camps, where he soon ended up.

Circumstances changed with the arrival of the Soviets, and many Polish and Yiddish-speaking authors decided to join the Soviet Writers Union of Ukraine. This was their only opportunity to protect themselves in the face of complete unpredictability. Indeed, the move enabled many of them to evacuate deep into Soviet territory after the German attack in 1941. Vogel did not do it. In her last surviving letter to her uncle Markus Ehrenpreis, she wrote that she was studying Ukrainian. The entire education system was switched to Ukrainian, so she had to learn the language to teach at a school where she received a job. Working in a Soviet school was the maximum Vogel could agree to. She understood only too well what communism was and how it poisoned the mind and creativity. She had written about it more than once in the 1930s.

The Nazis occupied Lviv in June 1941 and issued an order to establish the Lviv ghetto in the autumn. The Barenblüth family — Szulim, Debora, her mother, and her son — were forced to move. One November day, they left their home on Lisna Street forever.

Only one memory of Debora from her time in the ghetto survived until our day. An acquaintance met Vogel on the street and described her as "helpless and confused." He offered her a way to be rescued in a hideout on the "Aryan side." But she barely understood his words. "Such apathy was a death sentence. I never saw her again," he said.

The bodies of the Barenblüths were found in August 1942, after the so-called "liquidation action" in the ghetto. They were discovered by the artist Henryk Streng, who was friends with Vogel before the war. He worked in a Jewish unit tasked with cleaning the streets and found the bodies inside a shop behind a lowered shutter. Debora and her family had tried to hide there.

About three months later, Schulz was shot on the streets of the Drohobych ghetto. We only know where they died but not where they were buried. Their eternal home remains in their surviving words and writings. Their eternal home is in what we remember and write about them and nowhere else.

No place is named in honor of Debora Vogel in Lviv or elsewhere in Ukraine today. There is no mention of her at the house on Lisna Street where she lived. No trace. Did she understand that this is what often comes after loneliness, even when it is not destiny but a conscious choice? She probably did when filled with hope; she quoted the words of Karol Irzykowski at the end of her essay "Courage in Solitude": "There are no such lonely thoughts that would not be found, taken up, and understood by some other person somewhere."

Could we be that person or those people? There could be no other opportunity or time to finally "take up and understand" Debora Vogel's thoughts, which I hope will one day become "ours."

The works of Debora Vogel in Ukrainian: what to read (and watch)

Debora Vogel. Day-Figures. Mannequins. Translated from Yiddish by Yurko Prokhasko. Kyiv, Dukh i Litera, 2015.

Debora Vogel. Acacias Bloom. Montages. Translated from Polish by Yurko Prokhasko. Kyiv, Dukh i Litera, 2017.

Debora Vogel. White Words. Essays, Correspondence, Reviews, and Polemics / Translated and arranged by Anastasia Liubas. Kyiv, Dukh i Litera, 2019.

Iryna Starovoyt. Debora Vogel: A Searcher of Meaning in the Age of Totalitarianism.

Andriy Pavlyshyn. Debora Vogel.

Ostap Slyvynsky is a poet, translator, and literary scholar. He is the author of five poetry collections, numerous essays, columns, and reviews in Ukrainian and foreign periodicals. His works have been translated into 16 languages. He translates fiction and scholarly literature from English, Belarusian, Bulgarian, Macedonian, Polish, and Russian.

This material is part of a special project supported by Encounter: The Ukrainian-Jewish Literary Prize™. The prize is sponsored by the Ukrainian Jewish Encounter (UJE), a Canadian charitable non-profit organization, with the support of the NGO "Publishers Forum." UJE was founded in 2008 to strengthen and deepen relations between Ukrainians and Jews.

Originally appeared in Ukrainian @Chytomo

Translated from the Ukrainian by Vasyl Starko.