During the Second World War, Transcarpathia was one of a few regions where no pogroms took place, says historian Yuriy Slavik

A conversation about the Holocaust in Transcarpathia with the historian Yuriy Slavik, Candidate of Historical Sciences and researcher of the Holocaust in Transcarpathia.

Vasyl Shandro: When we talk about Transcarpathia and the history of Jewish habitation in Transcarpathia, to what degree is this topic underpinned by a body of reliable research?

Yuriy Slavik: The topic of the Jews of Transcarpathia and the Jewish community in this region is very under-researched, as is the Holocaust itself. The Holocaust caused the greatest population losses in our region during the Second World War. This once powerful and influential community, which was active in various spheres — economic, artistic, and cultural, etc. — disappeared. Our cities, the key subjects of which were the Jewish communities, changed drastically.

Today, this topic is poorly researched for certain reasons, not least of all because of the Soviet policy of historical memory whereby Jews did not figure among victims but were simply counted as part of the general losses of Soviet citizens during the war years. Practically no attention was devoted to the Holocaust topic. However, in the 1990s, this topic began to develop in the territories of the former Soviet Union. It appears in the information space, but from a scholarly standpoint, it is still poorly researched.

This topic has been studied in greater detail in the West. Many Jews who survived the Holocaust eventually settled in the US and Israel. Historians in these countries conducted research and collected the testimonies of witnesses to the Holocaust. Owing to a lack of sources in the territories of the Soviet Union, this topic was not sufficiently reflected.

Today, there is every opportunity to conduct research, and the topic is being developed. There is a study by the American historian Raz Segal, who examined the history of the Jews from 1918 to 1945, including the history of the Holocaust in Transcarpathia. However, this is one of a handful of works; meanwhile, this topic has immense potential.

Vasyl Shandro: Is there any data on the size of the Jewish population in Transcarpathia in 1938 and 1939?

Yuriy Slavik: Without a doubt, the Czechoslovak era left us with detailed descriptions of the population. Austro-Hungarian censuses are not as accurate as Czechoslovak ones, but judging by the presence of the Jewish faith, it was possible to determine how many Jews lived there. The last census of the Czechoslovak era (1930) recorded that some 12 or 13 percent of the inhabitants of the region were Jews; in cities like Mukachevo, Jews comprised 43 percent of the population. The community numbered around 90,000, the third-largest community in the region.

The Jewish community in Czechoslovakia lived in quite favorable circumstances. Everything changed radically after March 1938, when the region became part of Hungary after the Vienna Arbitration. At the time, there was already one antisemitic law in force in Hungary. A second one was under consideration in parliament; it anticipated many restrictions on the participation of Jews in the economic sphere and state governance. Naturally, this affected opportunities for the community.

It must be noted that even during the Second World War, Transcarpathia was one of a few regions where there were no anti-Jewish pogroms. Although antisemitism did exist, no pogroms ever took place.

Vasyl Shandro: Were Jews mobilized in Transcarpathia?

Yuriy Slavik: It should be noted that the political status of Transcarpathia during the Second World War was different from the rest of the territory of Ukraine, which was occupied by Nazi Germany. Transcarpathia was essentially part of the Kingdom of Hungary, and all laws applied to it. Residents of Transcarpathia were citizens of Hungary, and they enjoyed voting rights.

Residents of Transcarpathia were drafted into the Hungarian army, in whose ranks they fought. During the early years of the war, Jews were also mobilized. After 1940 Jews were mobilized for work in auxiliary labor detachments of the Hungarian army, where they carried out engineering work and dug trenches. Jewish labor battalions suffered the most because they were often used for laying mines on the Eastern Front. This practice continued until 1944. The Jews in these labor battalions avoided being killed in Auschwitz.

By March 1944, German troops were in Hungary. You have to understand that, despite the fact that Hungary had a state antisemitic policy, the conservative part of the Hungarian political arena opposed Hitler's attempts to destroy the Jews. They anticipated a restriction of the Jews' activities, but not their physical destruction. However, Hungary was occupied in March 1944, and the Germans took it upon themselves to implement the Jewish question. The Germans had to do everything quickly because the war was coming to an end. The local authorities also contributed to this.

Vasyl Shandro: How many people were killed? Was everyone brought to Auschwitz?

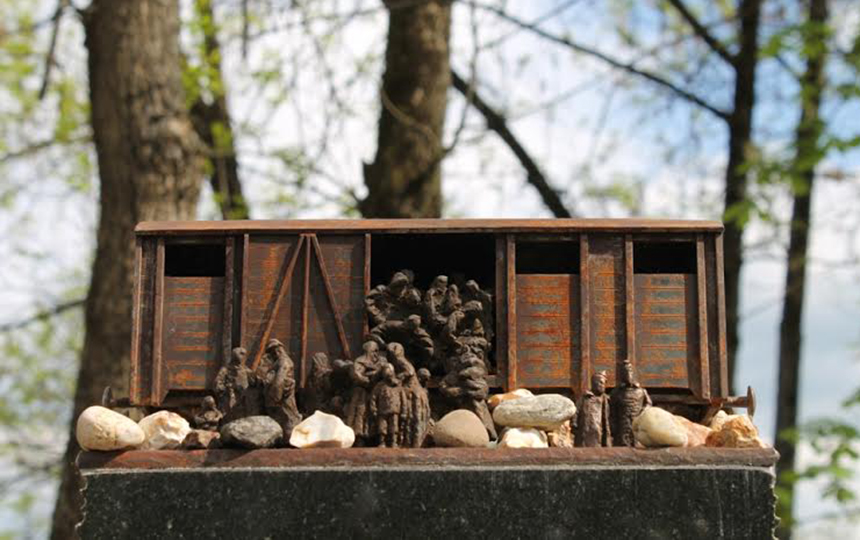

Yuriy Slavik: If we are talking about 1944, then all the trains from Transcarpathia headed to the city of Košice, and from there, gendarmes handed them over to their German escorts, and everyone was transported to Auschwitz, near Oświęcim. Most were deported to Auschwitz, where they were separated into groups. Physically able young people were sent to work, but the larger share was immediately sent to the gas chambers. Most did not survive.

The Extraordinary Commission that was created in the USSR after the war concluded that during the Second World War, 104,000 out of 115,000 people lost their lives. Only one in every ten people survived the Holocaust in Transcarpathia.

For the complete program, listen to the audio file.

This transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

This program is created with the support of Ukrainian Jewish Encounter (UJE), a Canadian charitable non-profit organization.

Originally appeared in Ukrainian (Hromadske Radio podcast) here.

Translated from the Ukrainian by Marta D. Olynyk.

NOTE: UJE does not necessarily endorse opinions expressed in articles and other materials published on its website and social media pages. Such materials are posted to promote discussion related to Ukrainian-Jewish interactions and relations. The website and social media pages will be places of information that reflect varied viewpoints.