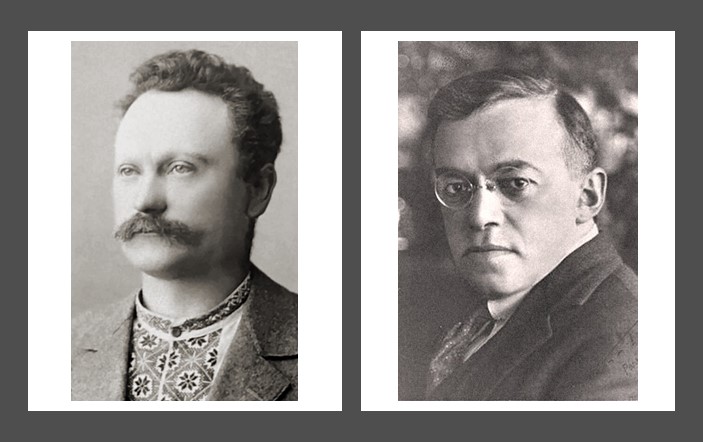

Franko and Jabotinsky: Setting the stage for cross-cultural understanding between Ukrainians and Jews

Two writers, two politicians. Two outstanding public figures. And two intriguing viewpoints on the historic challenges of Ukrainian-Jewish relations.

The Ukrainian writer Ivan Franko passed away in 1916. The Zionist leader Vladimir Jabotinsky was from a generation younger. Both made vital contributions to the creation of their respective national states of Israel and an independent Ukraine. But both did not live long enough to see their national dreams come true.

Wolf Moskovich, professor emeritus at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, compares and contrasts the lives of these two men in a fascinating essay. The essay was one of the contributions to an international conference and subsequent book on Ivan Franko and the Jewish issue in Galicia by the Vienna University Press.

There is no evidence Franko and Jabotinsky ever crossed paths, though both met intellectuals they knew in common. Professor Moskovich traces some remarkable similarities in both men’s life stories. Both men ran for an elective political office before the First World War, Franko for the Habsburg Austrian parliament, and Jabotinsky for the Imperial Russian Duma. And both were defeated by corrupt party machines that were hostile to the interests of the two men’s electorate.

Professor Moskovich calls Franko unique among Ukrainian writers of his times in his deep understanding of the Jewish community of Galicia. Franko apparently knew Yiddish from childhood and published some of his own translations of Yiddish works. Franko wrote more on Jewish subjects than any of his Ukrainian contemporaries.

And no Jewish leader before or after Jabotinsky devoted as much attention to Ukrainian national issues. His support of the Ukrainian national struggle remained consistent and his writings reflected only a positive attitude towards Ukrainians.

But there were inevitable differences.

Professor Moskovich points out that Ivan Franko could be considered ambivalent about the Jewish community. Some of Franko’s writing can be considered philo-Semitic. However Moskovich notes Franko depicts Jews in an unfriendly manner in some of his works of fiction and poetry.

Franko was evidently the first non-Jewish reviewer of Theodor Herzl’s 1896 landmark book The Jewish State, which called for the Jewish people of Europe to leave for their historic homeland. Professor Moskovich asserts Franko’s sympathy toward the Zionist idea did not originate in his deep Christian beliefs, as was the case with many Christian supporters of Zionism. Instead, Franko felt that the dire economic conditions of Ukrainians in Galicia, seen as Jewish exploitation, demanded the emigration of Jews as a safety valve. Herzl’s idea of a national state for Jews stimulated Franko’s own dreams of an independent Ukrainian state.

Franko believed pauperized Ukrainian peasants and workers should defend their economic interests by creating cooperative structures that would eventually eliminate Jewish middlemen. And yet Franko supported the recognition of Jews as a separate nation with full equality of rights and obligations.

Jabotinsky recognized the grave economic situation in Galicia and pursued Ukrainian-Jewish political cooperation. He saw the similarity in the national destinies of both peoples. Jabotinsky wrote that circumstances in Galicia were against the Jews. The only viable answer was to return to Zion and create the Jewish national state in Palestine.

Professor Moskovich notes that at the end of the day Jabotinsky understood competing interests and history would make it difficult to persuade Jewish leaders to cooperate with Ukrainians. So Jabotinsky stressed the importance of the two groups’ common interests.

He wrote: “I am not an optimist and I do not believe in ‘love’ between nations. In particular I do not in any way conceal from myself the fact that a certain antagonism exists between the Jews and Ukrainians of Galicia, one that takes on uncivilized forms. I am certain that those uncultured forms will disappear with the growth of education, but tribal conflicts will persist until there are fundamental changes in the political and ethnographic map of the world and in the socio-economic system.”

Changes did eventually come to Galicia, and to Europe, massive and cruel changes unimagined in the earlier and more genteel era of Franko’s lifetime. These were changes whose horrific contours Jabotinsky could already glimpse just before his sudden death by heart attack in New York in 1940.

Wolf Moskovich’s essay, titled “Two Views on the Problems of Ukrainian-Jewish Relations: Ivan Franko and Vladimir (Zeev) Jabotinsky,” can be found online at academia.edu.

This has been Ukrainian Jewish Heritage on Nash Holos Ukrainian Roots Radio. From San Francisco, I’m Peter Bejger. Until next time, shalom!

Written and narrated by Peter Bejger

Listen to the program here.

Ukrainian Jewish Heritage is brought to you by the Ukrainian Jewish Encounter (UJE), a privately funded multinational organization whose goal is to promote mutual understanding between Ukrainians and Jews. Transcripts and audio files of this and earlier broadcasts of Ukrainian Jewish Heritage are available at the UJE website and the Nash Holos website.