Gaining their respective statehoods was decisive in the Ukrainian and Jewish Scout movements—Yurii Yuzych

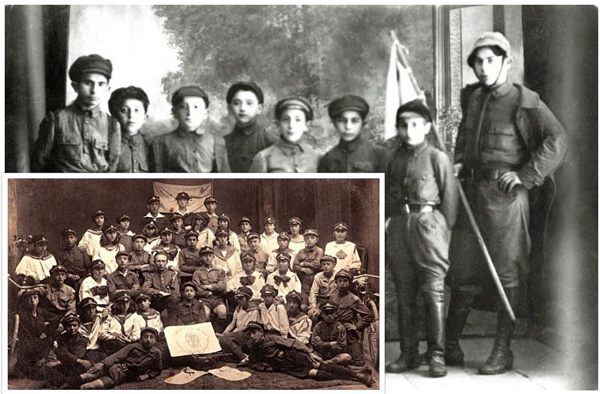

We are talking about the Jewish scout movement, which originated in western Ukraine.

Our guest today is the historian Yurii Yuzych, head of the Supervisory Board of the Plast youth organization.

Vasyl Shandro: When did Jewish Scouting appear?

Yurii Yuzych: It appeared approximately in 1910 and operated until 1943–1944 when the bulk of the Jewish population of Western Ukraine was killed. The Jewish Scout movement is derived not so much from the sports movement, as from the Zionist movement. The Zionists wanted to return to the Promised Land, to Palestine. They organized themselves into a strong Zionist movement. (Hashomer ha-tsa’ir aimed to educate and train its members specifically for immigration to a kibbutz in Palestine—Ed.) The sports movement made an impact on Plast, but in both the Ukrainian and Jewish Scout movements, there was a desire to organize young people to gain their statehood.

Vasyl Shandro: What was the Jewish Scouting organization called? Did it change its ideology or name during the years of its existence?

Yurii Yuzych: Scouting organizations in Eastern Europe sought some kind of appropriate terminology. Polish Scouts were called Harcerzy, and Ukrainian Scouts—Plastuny. Hungarian Scouts were known as Cserkész. Accordingly, Jewish Scouts chose the Hebrew word for “guardian”—shomer (from ha-shomer—Ed.), and the organization was called Hashomer.

Vasyl Shandro: What were the goals of these organizations?

Yurii Yuzych: The so-called Scout Law is important for all Scouts worldwide and has been translated into various languages. The content of these points differs somewhat. For example, for Polish Scouts, there was a point concerning abstinence from alcohol. Polish Scouts were the most numerous; therefore, these trends were automatically present in both Ukrainian and Jewish Scouting.

In Jewish Scouting, there was another particularly important issue that was connected with the interweaving of a religious foundation; for example, the question of premarital sexual relations. For Jews, this was one of the key questions in the formulation of the content of their national Scout movement.

Vasyl Shandro: Can one speak of some kind of systematic work with regard to training? Are these rules, norms, qualities, and traits that a Scout had to possess written down?

Yurii Yuzych: Jews obtained their first handbook during the First World War. Jewish Scouting organizers went to Vienna, where they wrote a Polish-language handbook explaining all the principles of Jewish Scouting. The handbook was in Polish because it was more prevalent among Galician Jews.

Vasyl Shandro: In other words, the Jewish Scout movement originated on the territory of Ukraine?

Yurii Yuzych: Yes, but there is one nuance. The Jewish Scout movement had two centers: one in Lviv and another in Warsaw. Later, the Warsaw movement became dominant. Still, for many years there were two offices.

Vasyl Shandro: What did Scouts do during their meetings?

Yurii Yuzych: All Scouts worked according to a single model. There were basic requirements that everyone coming into the organization had to fulfill: be able to start a fire, conduct a field trip. There were no politics as such.

The formula did not differ from what Plast does today. Minor nuances changed, but on the whole, everything today is the same as it was a hundred years ago.

Vasyl Shandro: Was this movement revived after the Second World War?

Yurii Yuzych: During the Second World War, there was an underground. There is not a significant number of Jews left in our country; they were killed, or they immigrated en masse to Israel.

In Israel, Hashomer branches existed until the outbreak of the Second World War. In 1916 settlers founded the Scouts organization Tzofim in Israel; its name means “scouts.” After the Second World War, it was recognized as a national organization. All the other forms of Jewish Scouting were forced to divest themselves of their Scouting elements. To this day, Hashomer is a big organization in the Jewish world, but it is no longer positioned as a Scouting organization.

Vasyl Shandro: Were there restrictions based on gender when one joined the Scouts?

Yurii Yuzych: This, too, was an interesting feature of Scouting in Lviv. Civic society in Austro-Hungary was more democratic, so women were included in various forms of organized life.

Whereas to this day, the Scout movement in America is divided into boys and girls, in Galicia, all three Scout movements—Ukrainian, Polish, and Jewish—were mixed from the outset. They worked in one and the same organization; however, educational units comprised of small groups of between twenty and thirty people, still functioned separately. The higher organization, on the town or district level, was mixed.

Vasyl Shandro: Were there contacts between the Jewish Scouting organization and, for example, the Ukrainian one during the interwar period?

Yurii Yuzych: There definitely were contacts. In Transcarpathia, there were four organizations that functioned in parallel: Czech, Ukrainian, Hungarian, and Jewish. There was even a small journal called Plastun, Cserkész, Scout, which was issued, in fact, by Ukrainians. We have traced dozens of Jews in Plast, as there was no local Shomer organization. Jewish children joined Plast and worked with Ukrainians.

This program is created with the support of Ukrainian Jewish Encounter (UJE), a Canadian charitable non-profit organization.

Originally appeared in Ukrainian (Hromadske Radio podcast) here.

Translated from the Ukrainian by Marta D. Olynyk.

Edited by Peter Bejger.

NOTE: UJE does not necessarily endorse opinions expressed in articles and other materials published on its website and social media pages. Such materials are posted to promote discussion related to Ukrainian-Jewish interactions and relations. The website and social media pages will be places of information that reflect varied viewpoints.