Godless people’ or bearers of new knowledge? The history of Jewish educators in Ukraine

How Jews began leaving their ghettoes for the spacious streets of large European cities.

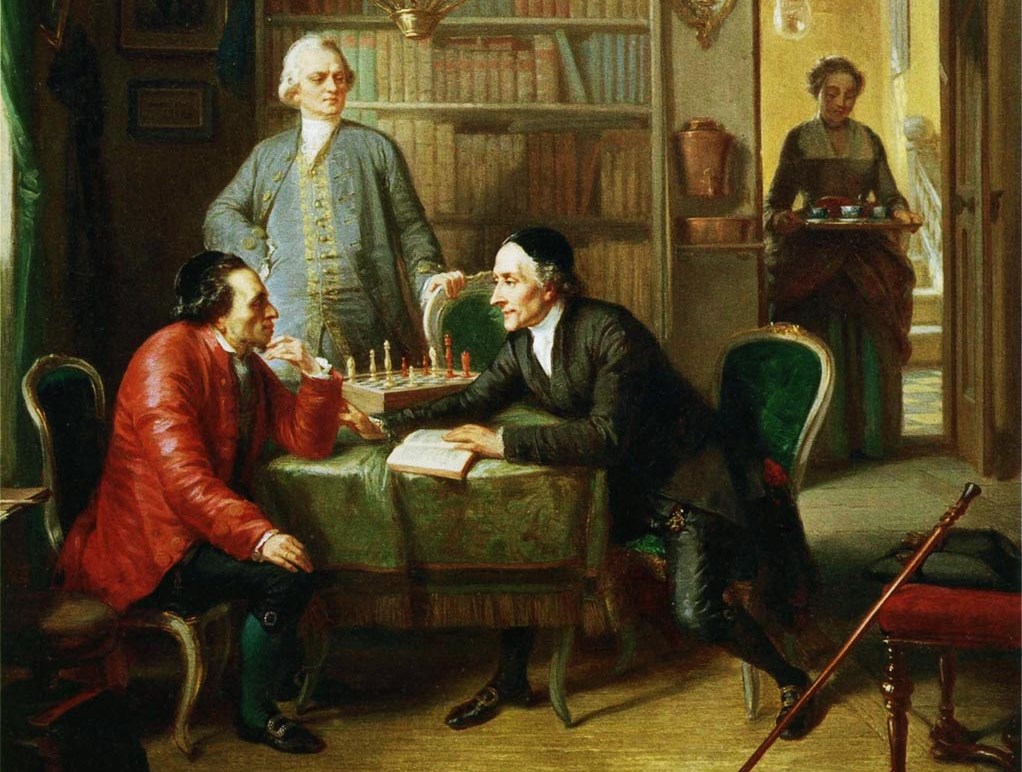

The Age of Enlightenment began in Europe in the eighteenth century. In this new system of ethics, the supreme value was Reason. The members of this movement made discoveries in physics, chemistry, mathematics, and other sciences, about which the world had known little before then. During this period Denis Diderot created the first encyclopedia [Encyclopedia, or a Systematic Dictionary of the Sciences, Arts, and Crafts].

The Enlightenment spread rapidly eastward, to the territories of the then Rzeczpospolita and the Russian Empire, which included the lands of contemporary Ukraine. Despite differences of religion, language, and social status, the Enlightenment found its niche in the culture of every people.

For example, there were many proponents of the Enlightenment among the professors and students of Kyiv Mohyla Academy. As early as the nineteenth century, Jadidism emerged among the Crimean Tatars, an educational movement that favored rapprochement between the Islamic and European cultures and called for a reform of Muslim life. Among the Jews this movement was known as the Haskalah, from the Hebrew word meaning “wisdom.”

The center of Jewish enlightenment was Berlin. Educated Jews sought to translate Enlightenment texts into their own languages and travel to Germany for their studies.

Kateryna Malakhova, scholarly associate of the Hryhorii Skovoroda Institute of Philosophy at the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine and a specialist in eighteenth-century Jewish history, Hasidism, and Jewish enlightenment, talked to us about the intellectual centers of Jewish enlightenment in the Ukrainian lands.

Kateryna Malakhova: There were numerous centers in Ukraine. In the early nineteenth century one of them was Ternopil, where the Jewish enlightener and educator Yosef Perl lived. Perl founded one of the first Jewish schools whose curriculum included not just traditional but also European subjects.

But this entire history begins earlier, not in the nineteenth but the eighteenth century. In fact, everything started in Berlin. One of the cities located in Ukraine or Poland today was Zamostia [Zamość, Lublin Voivodeship—Ed.], which was home to several large libraries. About the Zamość one it is said that it was brought from northern Italy, where European scholarship had been developing in the preceding centuries. And young Jewish men, dissatisfied with studying only the Talmud and Jewish classical texts, began to show an interest in that literature.

They began to translate various works into Hebrew, write treatises, for example, The Breath of Grace, a work by one of the first Jewish enlighteners, who lived on the territory of Ukraine. His name was Yisra’el Zamość. His treatise is a commentary on a medieval Jewish philosophical tract, but in the commentaries, he puts forward all the European ideas of the first half of the eighteenth century with which he was familiar. He talks about chemical elements and their corresponding masses; where rain comes from, etc. All this is absolutely chaotic and unsystematic. Later this Yisra’el Zamość travels to Berlin. [Moses] Mendelssohn, who is the main figure of the classical Jewish enlightenment, probably attended Yisra’el Zamość’s lectures on philosophy.

Andriy Kobalia: You mentioned Ternopil. What other centers of Jewish enlightenment were in Ukraine? Were all Jewish enlighteners from our lands connected with Berlin and German culture?

Kateryna Malakhova: Ternopil was a later center. There is the town of Sataniv. One of the Jewish enlighteners lived there, and he too tried to go to Berlin, from where he returned later. Menachem Mendel Lefin lived at the residence of Prince Czartoryski in Galicia and tried to translate Kant. There was also Buchach [today: Ternopil oblast—Ed.]. This city is connected with an individual who figured in my dissertation defense, Pinchas Hurwitz. He is an absolutely forgotten figure, about whom no one writes. A monograph came out in Britain after my defense.

Hurwitz’s biography is paradigmatic within the context of Jewish enlightenment. We don’t know where he was born; approximately in the 1760s. He lived in Buchach, where he had nothing to occupy his time. He wrote that he wanted to produce a treatise, but he did not know what to write about. One idea was Jewish mysticism. Unexpectedly, he contracted an eye disease and could not write anything. According to his account, he prayed and recovered. Later he travels throughout the world. He goes to Lviv, where he associates with wealthy people, who are able to sponsor him; then to Berlin, Pressburg, Amsterdam, the Hague, and London. In every city he sought to locate merchants; he told them that he was writing a treatise and requested money. He was given some and asked about the subject of the treatise. He replied, “about great wisdom.”

We know this because letters of recommendation from rabbis and merchants, with whom he stayed, are extant. Later, he says that this treatise is not just about great wisdom but about new European knowledge; in order to tell Jewish youths about it. And they provided funds for this. The treatise was published in 1797 in Brno [today: the Czech Republic—Ed.]. This was the first Jewish encyclopedia of the modern period. It was an account of everything. It contains the chemical elements, there are quotes from Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason.

That is roughly how it happened. These people sought to amalgamate Jewish traditional scholarship with new European knowledge. They roamed in search of knowledge and funds. Many intellectuals led this kind of difficult life. It is we today who can find some kind of grant to study.

Andriy Kobalia: We mentioned Jewish enlightenment for the most part in the territories of western Ukraine. After the partitions of Poland, the majority of those territories became part of Austria. Were there centers in the Ukrainian gubernias of the Russian Empire?

Kateryna Malakhova: We know very little about those centers. At the present time Jewish Galicia is better researched. But in the early nineteenth century there was a center in Uman. And this is an interesting history because it is connected with the famous Hasidic figure Nahman of Bratslav. We know that sometime in 1805 he went to Uman, perhaps in order to dispute with local enlighteners.

Here it is important to understand that Jewish enlightenment did not exist in isolation. The Haskalah movement was in a permanent state of war with Jewish traditional intellectuals, including the Hasidim, who were the representatives of the Jewish mystical movement.

Andriy Kobalia: What was the conflict between the proponents of the Haskalah and Hasidism? Were these quarrels limited just to the Ukrainian lands or did they exist everywhere?

Kateryna Malakhova: In order to understand this conflict, we have to realize what these enlighteners represented to the Hasidim. To us today, learning means progress. Most of the innovations stemming from knowledge make our lives better. But in traditional Jewish society, which psychologically was more similar to medieval society than to ours today, knowledge represented the danger of godlessness.

Andriy Kobalia: Thanks to Jewish enlightenment and secular culture, in the following decades Jewish political parties and Zionism emerged in the Ukrainian lands. However, the survival and development of Jewish culture often depended on the policies of central governments. Kateryna Malakhova talked about the vision of the Jewish future in Vienna and St. Petersburg.

Kateryna Malakhova: The Russian Empire recognized the Haskalah. With Hasidism, everything was more difficult. There are documents dating to the early nineteenth century in which educated Jews who spoke Russian and German wrote complaints to the government about the Hasidim. They say that the Hasidim are spreading “stupid beliefs,” and those who have fallen prey to these beliefs cannot be citizens of the empire.

Andriy Kobalia: In other words, the representatives of the Haskalah saw the Russian government as an ally? What kind of relationship existed between them and St. Petersburg?

Kateryna Malakhova: Most Jews arrived in the Russian Empire after the partitions of Poland. Before then, Jews came from Khazaria or other locales, but this is debatable. The first time that the empire confronts a huge number of citizens is after the partitions of Poland. And millions of Jews live in these territories. What should be done with them? Russian then adopts a pro- European and pro-enlightenment course. And the question arises: How to turn these uneducated people who do not speak “any decent language” into normal imperial subjects? At this very time Jewish enlighteners, who are able to assist the Russian government, emerge.

Andriy Kobalia: That is, in fact, to help the government to assimilate the Jews.

Kateryna Malakhova: Yes. There was nothing antisemitic about this. They wanted to turn them into ordinary citizens. During this period government-appointed “state rabbis” come about. Knowledge of Russian was mandatory, and they had to have completed gymnasium studies. They had to lead their community, so that the government could understand what was happening with them there. Rabbis usually came from educated circles.

Andriy Kobalia: We see that the Romanov dynasty wanted to integrate the Jews. What did the Habsburgs do about this in Austria?

Kateryna Malakhova: As far as I know, they tried generally not to interfere in their affairs. At least this dispute between the Hasidim and the Haskalah was regarded as an internal affair. Cooperation with the Austrian government commenced in the second half of the nineteenth century, when Jews began showing an interest in political life and parties. By the 1880s and 1890s in this empire they could take part in elections. Then an immense number of Jewish parties appeared, mostly Zionist ones, but there were also several specifically Hasidic parties. For example, there was a Hasidic party in the city of Belz [today: Lviv oblast—Ed.] At the end of the century various Jewish parties participated in political life. But in the early part of this century there were no attempts in Austria to intervene.

Andriy Kobalia: You already mentioned the late nineteenth century, when perceptions of what the narod was had changed. There was such a thing as nationalism. In those years political parties appear among the Ukrainians, Jews, and Czechs. This process is taking place in both empires as well as in Europe. Jumping ahead, I would like to know how the conflict ended between Jewish enlighteners and the traditionalist Hasidim?

Kateryna Malakhova: It did not end. Historically, the Haskalah won. The Jewish community, which at the end of the century considered itself a secular community, now comprises 90 percent of the Jewish population. But these traditional groups that belong to the Hasidic movement have been preserved to this day. Of course, like everyone, they too suffered during the Holocaust. But the descendants of the leaders of the Hasidic dynasties that had existed in numerous small towns immigrated to America and Israel and conserved traditional communities that avoid contacts with the outside world and speak Yiddish to this day continue to exist in the contemporary world. With the outside world, they engage mostly in business. They live within their closed world, and do not let anyone in. Their history continues.

This program was made possible by the Canadian non-profit organization Ukrainian Jewish Encounter.

Originally appeared in Ukrainian (Hromadske Radio podcast) here.