Guido Hausmann: “I think that to this day German scholars have not discovered the Holodomor topic.”

“For a long time, it was difficult for me to comprehend and get a sense of Ukraine”

Dr. Hausmann, please tell us where you were born and raised.

I was born and grew up in a village located a hundred kilometers east of Cologne, in the historic region of Westphalia. This is an agricultural area, where the preponderant majority of the population is Catholic. When I was a child, I played soccer nearly every day. I had five brothers and sisters. My father was a veterinarian. I lived in my village until I was eighteen. Part of my family came from the Netherlands. We also loved France a lot. So, our family often traveled to the Netherlands and France, at least once a year.

What was your first university major?

I studied German language and literature at the University of Münster, Westphalia, because I wanted to be a journalist. I began testing myself in the role of a journalist, when I was only eighteen. However, eventually, I decided that this would not be my true profession. I was very interested in Spanish history and the Mayan culture. So, I changed my major and began taking history classes when I was still in Münster. But a real focus on history came when I switched to the University of Cologne.

What influenced your choice of Eastern Europe as the focus of your academic studies?

The search for a research focus during the initial period of my studies was a serious challenge for me. During the first half of the 1980s, I attended a few seminars on Eastern Europe. At the time, I knew practically nothing about the history of Eastern Europe in general and of Ukraine in particular. I didn’t have any personal connections, even with East Germany. Some of my peers had relatives and friends in East Germany and Poland. They often traveled there, so they had much greater experience and practical knowledge about life in communist countries.

Were you Andreas Kappeler’s first graduate student?

Yes, it’s quite likely that I was one of his first, perhaps even the first of the graduate students who were working under his supervision in Cologne. At that time, he had just been hired as a professor at the University of Cologne. Professor Kappeler gave a series of important lectures on Russian history from the Middle Ages to the twentieth century. Since I was very unfamiliar with this field, I was fascinated and decided to attend Kappeler’s lectures. Sometime later, I attended a seminar that he organized. There I found out that he was launching a new scholarly project to do research on the very first census in the Russian Empire, which was carried out in 1897. Professor Kappeler invited me to join his research group. That is how I began to collaborate more closely with him and integrate myself into Eastern European Studies.

Why did you choose the history of Odesa as your dissertation topic?

At first, Kappeler proposed that I write a dissertation about the University of Kyiv. I decided, however, that Odesa would be more interesting to me. My research focused on civil and national movements in Odesa, specifically the Odesa University, the various national groups that studied there — members of the urban elite. The title of my dissertation was “Novorossiia University and the Development of a Civil Society in Odesa, 1865–1917.”

Can you provide more details about the key findings of your dissertation?

My dissertation and the book that is based on it are devoted to the emergence of a civil study in Odesa in the second half of the nineteenth to early twentieth centuries. I analyzed the main factors that accelerated or slowed down the birth and development of a civil society in Odesa during this period. I concentrated on the local Novorossiia University, which was founded in 1864, and researched its role in these processes. I analyzed the social composition of the student body, their professors and their role in the formation of the Russian, Jewish, Ukrainian, and Polish national movements and civil society until the collapse of the Russian Empire. I used the social space and resource model of the sociologist Pierre Bourdieu and tried to analyze the city as an integrated space of various national and social groups. The research entailed rather complex and painstaking empirical work. For many years I examined periodical publications and archival documents in Odesa, Kyiv, and St. Petersburg. I began working in Ukrainian and Russian archives in the late 1980s. The first time, I went there to work with a large group of German graduate students. We traveled to Moscow by train from Cologne via Berlin, Warsaw, and Minsk. I remember that, because of a malfunction, the train stopped somewhere in the eastern part of Poland. For nearly half a day, we sat next to the train station, waiting to continue our journey. Then we went to Moscow. Most of the German graduate students who were doing Eastern European Studies remained there. Some went to Leningrad. I was the only one in our group to head southward, to Kyiv and Odesa. At the time, I spoke only a little Russian and had barely any knowledge of Ukrainian. However, over time I deepened my knowledge.

Do you have any personal recollections of your first stay in Kyiv and Odesa?

I got to know my first Ukrainian friends at this time. In Odesa, where I was staying, I attended one of the first Ukrainian national demonstrations to take place in this city. No more than fifteen people participated. I remember an elderly woman who recited a poem during the demonstration. I think it was written by Taras Shevchenko, but I don’t recall exactly anymore. In the past, I had never taken part in any demonstrations where poetry was recited, and this moved me deeply. From those times, I remember Vasyl Shchetnikov and Anatolii Bachynsky; regrettably, both of them are now deceased. Bachynsky was one of a handful of members of the Odesa intelligentsia who spoke Ukrainian in public at the time. It was fascinating for me to observe these national processes in the city.

Which Ukrainian historians did you know at the time?

In 1991 Andreas Kappeler held a conference in Cologne. This was the first conference in Germany devoted to the history of Ukraine. Among the Ukrainian scholars who attended this conference, I remember Yaroslav Dashkevych, Yaroslav Isaievych, Mykola Zhulynsky, Frank Sysyn, and Bohdan Osadchuk.

Are you continuing to work on the history of Odesa?

Recently I have been invited to join an interdisciplinary German-Israeli research group at the Israel Institute for Advanced Studies of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, which is working on a project called “Cosmopolitan Spaces in an Urban Context: A Case Study of Odessa, 1880–1925.“ I joined this group temporarily, only for half a year. We were supposed to work in Jerusalem, but because of the pandemic, it took place on Zoom. Today I am also planning to do research on the history of Ukrainians and the Black Sea.

Was your book about Odesa published in Ukrainian or Russian?

No, it was too expensive for me. At one point, we discussed the idea of issuing my book about Odesa in Ukrainian. Polina Barvinska was very much interested, but we still have not realized this plan. The book focuses on a very narrow set of questions connected with the history of one city, although it has a comparative attention to Kharkiv and Kyiv. It may have found a readership in Odesa, but not among the general Ukrainian public. This is an academic study, oriented mostly on a narrow circle of scholars.

Dr. Hausmann, why did you finally decide to take up Ukrainian Studies?

The path to studying Ukrainian history was complicated. Odesa is situated on the margins of the Ukrainian national narrative. Every year in the 1990s, I visited Ukraine (mostly Kyiv and Odesa). For a long time, it was difficult to get a sense of Ukraine. Nonetheless, over the years of my scholarly research, I became increasingly accustomed to Ukraine’s cultural and political characteristics and gradually integrated into understanding its past. I got to know many Ukrainian historians, including Serhii Stelmakh of the Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv. We first met when I was working in the Odesa archives. One time we arranged to organize a Ukrainian panel at an international conference. Since then, we have been meeting periodically, every time that I am in Kyiv. Starting in 2001, we have been organizing seminars for young historians.

One of your most fascinating projects is devoted to the Poltava region. Can you expand on this?

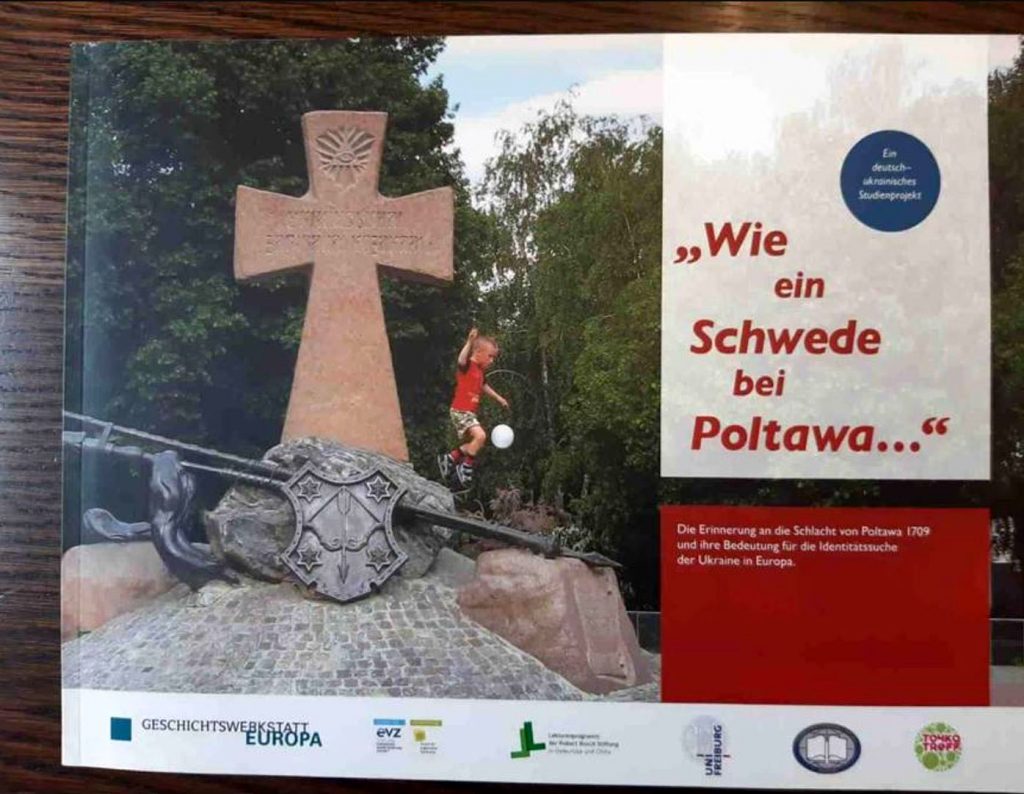

The idea for this project did not come from me but from a representative of the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) in Poltava. She e-mailed me an invitation to join this prospective scholarly project devoted to the history of the Battle of Poltava and the culture of memory about it in contemporary Ukraine. I agreed, and we applied for financing. The project was linked to student exchanges and academic research. This project was focused mainly on the culture of memory in Ukraine, particularly the memory of the Battle of Poltava. Its realization was the result of the work done by Ukrainian students from Poltava and German students from Freiburg.

One of your projects concerned the history of famine in the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union (from the late nineteenth century to 1946). Could you provide more details about how you arrived at this project?

This took place thanks to close collaboration with my colleagues. One of the initiators was Dietmar Neutatz from Freiburg. At the time, he was working at the University of Freiburg. Previously, he had been researching the history of German colonists in southern Ukraine in the late nineteenth–early twentieth centuries. In the 1990s, this topic became particularly popular. However, by the late 1990s, the majority of empirical studies had been completed. He had decided to organize a conference on the topic of famine in the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union. The conference was held in November 2010 near Göttingen. During the conference, I noticed that the organizers were avoiding the topic of the Holodomor of 1932–1933, perhaps for fear that the exceedingly politicized question of its genocidal nature might overshadow the entire event. After the conference, I decided to write an article about the place of the Holodomor in German historical scholarship.

One professor who is studying the Holodomor is Gerhard Simon. Was he present at this conference?

No, he wasn’t at the conference, but we are still in contact to this day. We see each other most often at the Lew Kopelew Forum in Cologne. He was one of the scholars who, during the 1980s, was interested in the history of national groups in Eastern Europe. He is quite well known among those who study this topic and advance Ukrainian Studies.

At the time, few people in Germany were working in the field of Ukrainian Studies. Only three well-known scholars focused on them: Andreas Kappeler, Gerhard Simon, and Frank Golczewski.

Yes, Frank Golczewski was also doing research in Ukrainian history in Hamburg. He is still overseeing important academic projects being done by graduate students who are researching the history of Ukraine. Simon specialized in political science, which is why he was studying not only the past but also contemporary political processes in Ukraine. Another German historian who was advancing Ukrainian Studies in the German academic milieu is Rudolf Mark. At present, he is writing a monograph on [Symon] Petliura.

How would you describe the transformation of Ukrainian Studies in Germany in the last thirty or forty years?

In my view, most of the historians who were working in this field came from research on the history of Russia or Poland and then focused on one aspect or another of Ukraine’s history. Some young researchers wrote doctoral dissertations on the history of Ukraine. However, in our country, we do not have many professors researching exclusively Ukrainian topics. This is partly connected to the fact that in Germany, it is quite difficult to obtain a professorial appointment by studying the history of Ukraine. In the context of Eastern European Studies, Poland and Russia are still more important to the German academic world. Today, however, we have noticed a trend marked by an increase in the number of studies, the subject of which is the history of other Eastern European states. In more recent years, Ukraine and Belarus have increasingly become the focus of German academic studies too.

As far as I know, quite a few German scholars who deal with Eastern European and Ukrainian Studies do not teach in Germany. They have found positions in the UK, France, or elsewhere. For example, Christoph Mick who works at the University of Warwick (Coventry, England). Considering the specific features of the German academic system, it is very difficult to obtain a professorship there.

Yes, that’s true. However, it is worth keeping in mind that right now a European “market” of academic studies is being formed. I am talking about European Studies and European history with a focus on Eastern Europe, not just the history of individual nation-states.

“To a certain extent, the Holodomor was considered a ‘right-wing’ topic in Germany. This is the hidden conflict that has existed outside of official discussions and academic research.”

How would you assess the place of Holodomor Studies, considering this context?

I think that German scholars have not discovered the Holodomor topic to this day. I would say that the article which I recently published with my co-author Tanja Penter is an attempt to find a path toward opening up this research subject in Germany.

Why, in your opinion, has such a situation come about in Germany? After all, in most Western countries, there are at least one or two historians who are studying the Holodomor.

It is difficult to explain. My recent article devotes a lot of attention to why it is so difficult for this topic to be introduced into the German academic world. In the early stages, when Holodomor Studies were emerging (in the 1980s–early 1990s), they already used the term genocide. It appeared even before any serious research had been done on the history of the Holodomor. Such an approach fundamentally restricted the space for other interpretations because they created specific expectations how to regard the facts. For German scholars, this was a demotivator. This trend signified that the topic seemed to be already closed for discussion.

I am a bit confused because you said that in the early 1990s, there was already a consensus of opinion that the Holodomor was an act of genocide. But at the time, no such consensus existed, not even in Ukraine.

Yes, that’s true. However, a very influential and dominant interpretation of the Holodomor existed on the international level. And every young scholar who began to research the Holodomor had to face its interpretation as a genocide. Moreover, during that period (in the 1980s and early 1990s) there was an ongoing, serious discussion in Germany about the Holocaust and its place in German and European cultures of memory. It was this combination of circumstances that may have inadvertently prevented the Holodomor’s entrée into German academic studies.

I think there was a German scholar who was researching the famine. But he was trying to explain it by natural factors, climate features, etc.

You’re probably thinking of Stefan Merl. He began his research in the field of economic history, not the study of nations and nationalisms. This scholar examined the Holodomor within the broader context of the Soviet struggle against the peasantry. There is another important factor: The world perception of scholars, such as Stefan Merl, Andreas Kappeler, and most of the representatives of this generation of historians who were involved in Eastern European Studies, was formed in the 1960s. Thus, to one degree or another, they were left-wingers. This is important for understanding not only the German but also the entire Western European context of academic studies of the Holodomor because the Holodomor was considered a “right-wing” topic. This is the hidden conflict that existed outside the official discussions and academic research. Discussions of the Holodomor were thus marked by this interpretive framework.

So, to a certain degree, the situation surrounding research on the Holodomor in Germany is conditioned by the reigning political climate that was formed by the Sixties generation. For them, the most important history was the history of the Holocaust, the magisterial component of German collective memory. In this context, can we say that the Holodomor looks like an alternative to the Holocaust? In other words, is there a conviction that discussions of the Holodomor can in some way decentralize the Holocaust as a founding concept of German historical memory?

Your hypothesis is correct. The Holocaust and the culpability of German criminals are fundamental to historical research in Germany. Thus, the existence of another crime, in which the Germans do not appear in the role of criminals, is somewhat puzzling.

I am not using these thoughts as an argument; I am only expressing my own feelings and suppositions. Perhaps there is a conviction that Ukrainians shifted the focus of their attention to the Holodomor because they deny responsibility for their involvement in the crimes of the Holocaust? However, my key hypothesis is that, in a way, the Holodomor and the Holocaust are not compatible with each other. Does this situation have something to do with Nazi propaganda of the 1930s?

It is difficult to say unequivocally. However, in 1933 Nazi leaders (particularly Hitler) made declarations in an anti-Soviet spirit about a famine taking place in Ukraine, a country that was so rich in agriculture. But such statements occurred infrequently, and I think they disappeared from the Nazis’ public rhetoric after 1933.

Can we say that the Nazis put an end to discussions of the Holodomor and did not mention this topic until the occupation of Ukraine in 1941?

Yes. This is probably connected with the Treaty of Rapallo and the cooperation between the two states that had lost the First World War. The Nazis were forced to safeguard their diplomatic relations from harmful ideological influences. They wanted to maintain good relations with the Soviet Union. This is why the Nazi regime tried not to initiate serious discussions about the Holodomor in Ukraine.

But the question of the Holodomor was revived during the Nazi occupation of Ukraine.

Yes, in 1941–1943, the Holodomor topic returned to Nazi propaganda. And this influenced the formation of the rather complicated perception of the Holodomor in German historical consciousness.

Can we say that German discussions about the Holodomor are still overshadowed by Nazism?

Of course. I completely agree with this statement.

Recently you wrote a serious scholarly article about the Holodomor. I hope that it will be translated into Ukrainian. I was puzzled by one of the arguments that you put forward. At the end of the article, you write that in the early 1990s, when Ukrainians launched discussions about the Holodomor, they had not discovered this issue; the Nazis had done this earlier. I see no connection between reviving the memory of the Holodomor in the 1990s and the fact that the Nazis had used this topic in their propaganda in the 1940s.

Of course, there was no connection between these two processes. I did not mean that. Tanja Penter and I were merely stating that there have already been numerous attempts to investigate this issue and to gather sources. Perhaps my thoughts were interpreted not quite correctly.

Maybe there is just a single sentence at the end of the article. However, it seems that there is an image in the West of Ukraine as a very antisemitic country. Romania and Poland today have a similar image. Does this somehow affect the perception of the Holodomor topic in Germany?

Such an image of Ukraine has existed twenty years ago. But I think that since that time essential changes have taken place. I personally know many young Ukrainian researchers who are doing research on the history of the Holocaust and the Second World War. So, for me, this image of Ukraine has long since sunk into oblivion. However, if we are talking about those scholars who do not specialize in Ukraine or Eastern Europe, then that perception of Ukraine may persist among them to the present day. Generally, however, this image of Ukraine in the German academic milieu has undergone essential changes in a positive direction.

“It would be important for Ukraine to establish an influential international center that would consolidate scholars from various countries who study the Holodomor.”

Not so long ago, the German-Ukrainian Historians’ Commission was publicly criticized for failing to make the Holodomor topic adequately known in Germany and to recognize it as an act of genocide. How do you assess the chances of the Holodomor’s being recognized as genocide in the Bundestag?

I think that this problem concerns not so much the Holodomor as the legal definition of the concept of “genocide.” However, I am not certain that a change of definition will be of great importance for discussions of the Holodomor in Germany. What is key for our country is the search for our own path to Holodomor Studies. In my view, simple recognition of the Holodomor as genocide would be inadequate.

Discussions are continuing in the international arena about the definition of “genocide” and the “correctness” of its definition. Are similar discussions taking place among German genocide researchers?

Such discussions are taking place mostly among scholars at the international level. They have made serious inroads in the German academic world. In Germany in the last thirty or forty years—and this is very important for the Holodomor’s entree into the world of German academic research—comparative studies of genocides did not develop. This approach to the study of genocides is prevalent in the United States, Canada, and other countries. We lack these discussions of genocides from a comparative perspective.

Rumors are circulating in Ukraine about Russian influence in Germany, which is causing an unwillingness to recognize the Holodomor as genocide. How would you comment on this?

It is possible that this factor truly does have an effect, but I am not sure. I don’t really understand why Russia perceives the question of the Holodomor in such a provocative manner. After all, Russia is not the Soviet Union. Thus, it could form a completely different attitude to this topic. I think that a change in the political situation in Russia will also affect its attitude to the Holodomor.

To what extent are public discussions of the Holodomor perceived in Germany as a manifestation of nationalism and the result of the Euromaidan, which is also partly perceived in a nationalist context?

This is true. There are certain groups in Germany that treat the Maidan as a manifestation of nationalism. However, in the current public sphere, we also have other large groups and political forces that interpret the events of the Maidan completely differently. They do not see in them any expression of nationalism but consider it a political revolution in the direction of building a democratic society. The emergence of such an influential interpretation is a new and positive shift in Germany’s public life.

In conclusion, I would like to note that we can discuss the question of the Holodomor in the context of the contrast between two opposing interpretations: was it genocide or not? However, I think that it would be more important for Ukraine to establish an influential international center that would unite scholars from various countries who are studying the Holodomor. This would signify the emergence of a platform for global discussions of the famine. The creation of such an international center would have a serious impact on Holodomor Studies and would emphasize the importance of such research for contemporary Ukraine. Of course, there are institutions in Ukraine that are engaged in the study of the Holodomor, for example, the Holodomor Research and Education Consortium (HREC). However, it does not work on a level that would draw the attention of German scholars. There are quite a few researchers with international reputations who contribute to research on the history of the Holodomor, for example, Andrea Graziosi and Frank Sysyn.

Do you think that the German-Ukrainian Historians’ Commission could support this?

This year we will hold a conference on the Holodomor. And this is a great opportunity to think about how we can open up this topic in Germany. I very much hope that we will fully capitalize on this opportunity.

Interviewed by Yaroslav Hrytsak.

This publication contains photographs from Guido Hausmann’s private archive and open sources.

Guido Hausmann is a professor of History of Southeast and Eastern Europe at the University of Regensburg, where he specializes in the history of Russia, the USSR, and Ukraine. He is the head of the History Division at the Leibniz Institute for East and Southeast European Studies (one of the three largest scholarly research institutes engaged in the study of Central and Eastern Europe in Germany, along with the scholarly research institutes at the universities of Marburg and Leipzig). At the Leibniz Institute, he also coordinates scholarly research on personalized and formalized administration. He is the main researcher at the Higher School for the Study of Eastern and Southeastern Europe (Munich–Regensburg) as well as the co-head of the research module at the Leibniz campus. Professor Hausmann is a member of the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) for 2021–2025 and the German-Ukrainian Historians’ Commission (DUHK). Since 2018 he has organized a winter school in Ukraine together with Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich and the Ukrainian Free University (Munich). Since 2001 he and Prof. Serhii Stelmakh have been holding seminars for young historians. Hausmann, together with Kappeler, edited the publication Ukraine: Gegenwart und Geschichte eines neuen Staates, and co-edited the book Wie ein Schwede bei Poltawa ... with Romea Kliewer (with the participation of students from the universities of Freiburg and Poltava). He was a member of the research project initiated by the University of St. Gallen (Switzerland) entitled “Region, Nation and Beyond: An Interdisciplinary and Transcultural Reconceptualization of Ukraine.” The English-language publication of its research findings will be published this spring by the academic publishers Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht in Göttingen (the Ukrainian historian Iryna Sklokina co-edited this book). Hausmann is the author of the monograph Universität und städtische Gesellschaft in Odessa, 1865–1917 and a number of articles on various Ukraine-related topics, including the geographer Stepan Rudnytsky, the Battle of Poltava, the instrumentalization of history, Ukraine in the First World War, Babyn Yar, Holodomor Studies in Germany, and the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk in Ukrainian and Russian historiographies.

Guido Hausmann is a professor of History of Southeast and Eastern Europe at the University of Regensburg, where he specializes in the history of Russia, the USSR, and Ukraine. He is the head of the History Division at the Leibniz Institute for East and Southeast European Studies (one of the three largest scholarly research institutes engaged in the study of Central and Eastern Europe in Germany, along with the scholarly research institutes at the universities of Marburg and Leipzig). At the Leibniz Institute, he also coordinates scholarly research on personalized and formalized administration. He is the main researcher at the Higher School for the Study of Eastern and Southeastern Europe (Munich–Regensburg) as well as the co-head of the research module at the Leibniz campus. Professor Hausmann is a member of the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) for 2021–2025 and the German-Ukrainian Historians’ Commission (DUHK). Since 2018 he has organized a winter school in Ukraine together with Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich and the Ukrainian Free University (Munich). Since 2001 he and Prof. Serhii Stelmakh have been holding seminars for young historians. Hausmann, together with Kappeler, edited the publication Ukraine: Gegenwart und Geschichte eines neuen Staates, and co-edited the book Wie ein Schwede bei Poltawa ... with Romea Kliewer (with the participation of students from the universities of Freiburg and Poltava). He was a member of the research project initiated by the University of St. Gallen (Switzerland) entitled “Region, Nation and Beyond: An Interdisciplinary and Transcultural Reconceptualization of Ukraine.” The English-language publication of its research findings will be published this spring by the academic publishers Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht in Göttingen (the Ukrainian historian Iryna Sklokina co-edited this book). Hausmann is the author of the monograph Universität und städtische Gesellschaft in Odessa, 1865–1917 and a number of articles on various Ukraine-related topics, including the geographer Stepan Rudnytsky, the Battle of Poltava, the instrumentalization of history, Ukraine in the First World War, Babyn Yar, Holodomor Studies in Germany, and the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk in Ukrainian and Russian historiographies.

This project is supported by the Canadian charitable non-profit organization Ukrainian Jewish Encounter (UJE).

Originally appeared in Ukrainian @Ukraina Moderna

Translated from the Ukrainian by Marta D. Olynyk.

Edited by Peter Bejger.

NOTE: UJE does not necessarily endorse opinions expressed in articles and other materials published on its website and social media pages. Such materials are posted to promote discussion related to Ukrainian-Jewish interactions and relations. The website and social media pages will be places of information that reflect varied viewpoints.