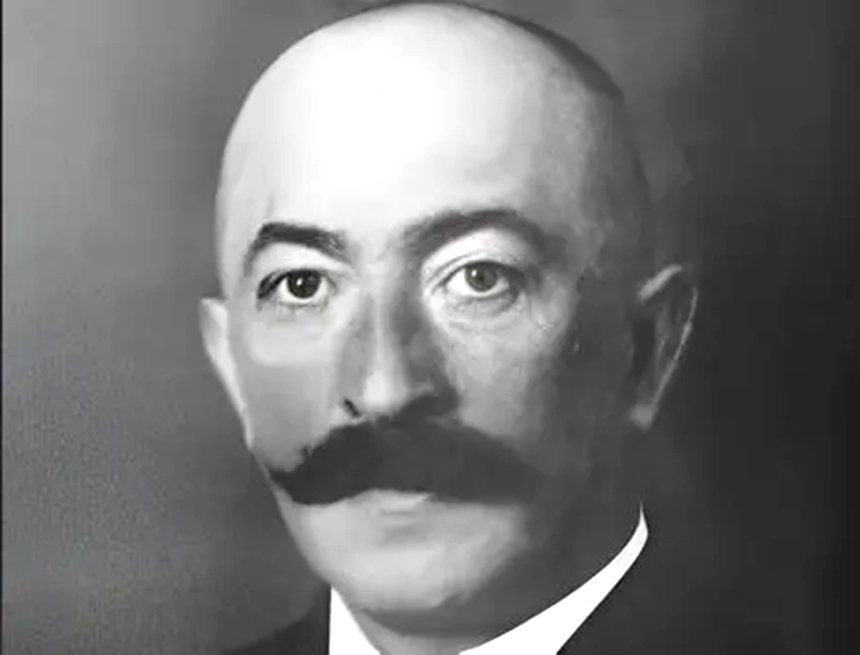

He purchased planes for the UNR and published Ukrainian books. Who was Yakiv Orenstein?

In this episode of the Encounters program, we discuss the life and professional activities of the outstanding book publisher Yakiv Orenstein.

Why little is known about Yakiv Orenstein

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: Our guest today is Professor Ivan Monolatii, a historian and the author of a work on Yakiv Orenstein and interethnic relations in Galicia. Orenstein was a remarkable figure who made a significant contribution to Ukrainian history. However, I've read that we have very little information about his life. Why is that so, and what is Orenstein's achievement?

Ivan Monolatii: The likely reason is that we still lack original documents concerning the life of this outstanding 20th-century Jewish publisher of Ukrainian books who was especially active before 1933. Another reason to be considered is that Jewish culture and publishers were marginalized in the Ukrainian discourse and the entire 20th-century Ukrainian project. Let's keep in mind that this was a century of totalitarianism.

Then, there is a lack of interest from Ukrainian scholars and Jewish researchers, who still call Orenstein a marginal figure in Ukrainian-Jewish relations.

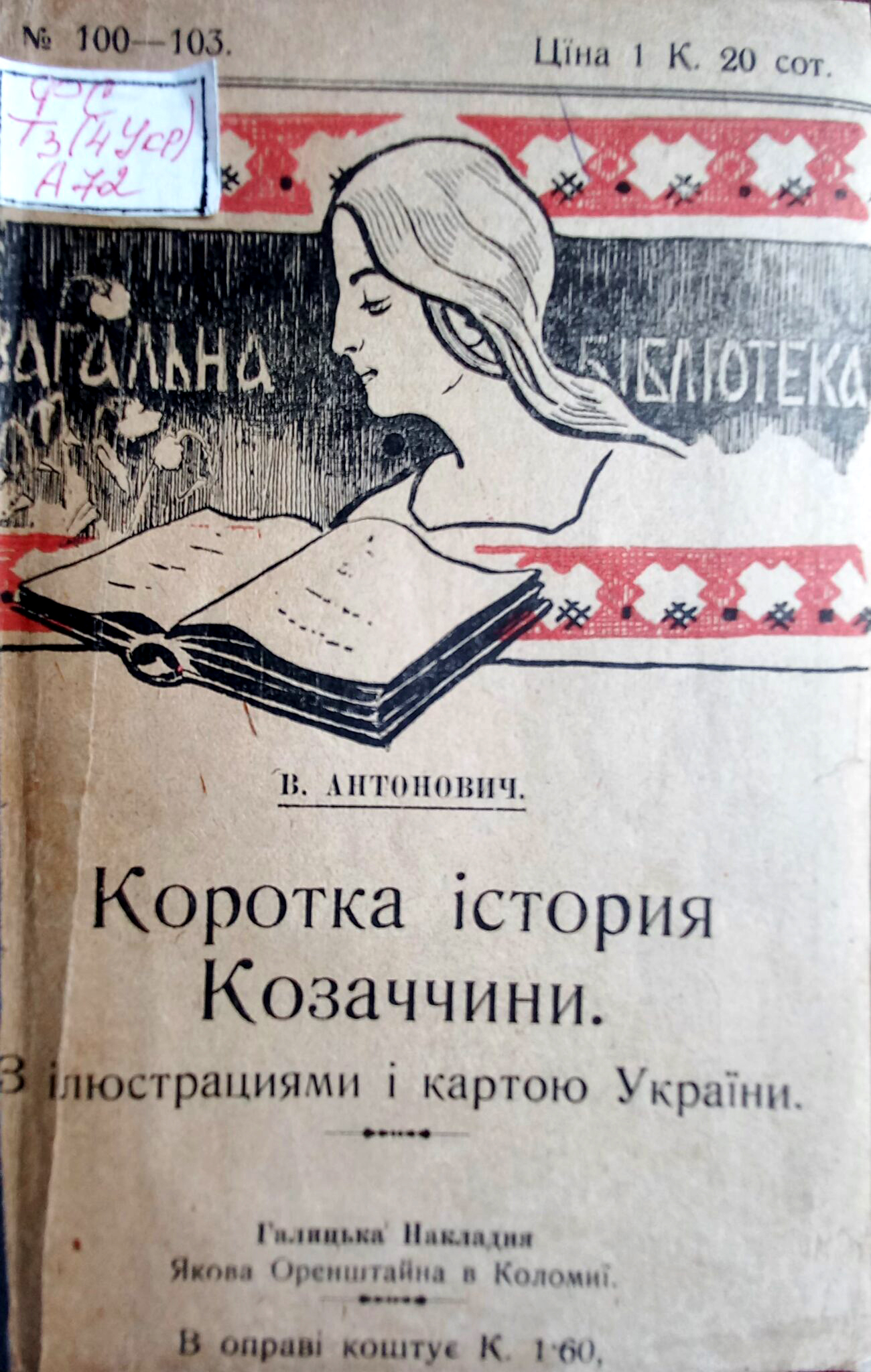

However, Orenstein made an invaluable contribution as an informal promoter of Ukrainian culture in the first half of the 20th century. He had the honor of giving Ukrainian culture — often for the first time — high-quality Ukrainian translations of world literature and specialized works in philosophy, sociology, psychology, and history.

Curiously, Orenstein did not publish a single Hebrew or Yiddish book, attempting to get involved in a number of national projects instead. He started with the Polish project and drew closer to the Russian one for a while, but the Ukrainian project became most significant in his publishing biography. It was claimed for a long time that he paid with his life for promoting the Ukrainian cause. However, I was able to establish that he was killed by the Nazis in the Warsaw Ghetto in 1942.

What made Orenstein stand out

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: The blurb on your book about Orenstein says that his life deserves a serious novel or a film. Why do you think so, and why don't we have a literary or cinematographic work about this figure?

Ivan Monolatii: Indeed, no works of this kind exist as yet. There were only a few episodes of Vakhtang Kipiani's Historical Truth program on the ZIK channel where Orenstein's publishing activity was compared to that of Ivan Tyktor.

Orenstein and his activities were of interest to such outstanding Ukrainian figures at the time as Symon Petliura, Mykhailo Hrushevsky, Volodymyr Vynnychenko, Yevhen Konovalets, and Andrey Sheptytsky.

Despite being a book publisher, Orenstein did not have his own printing or publishing house. He only owned a registered publishing brand and actively cooperated with Ukrainian migration institutes starting from the 1920s when Ukraine was, unfortunately, stateless. This did not prevent him from buying planes for the air fleet of the Ukrainian National Republic and acting as a diplomatic adviser to the UNR embassy in Germany. He was also a mediator between the Ukrainian Military Organization (UMO) and international Jewish organizations in the context of a cause célèbre when Stanisław Steiger was accused of an assassination attempt on the president of Poland. We also have evidence suggesting that Orenstein tried to help set up a Ukrainian university in interwar Galicia, which was under Polish occupation.

Therefore, I think that every educated person should talk about Orenstein. The Ukrainian writer and public figure Roman Ivanychuk once noted that every noble Galician (read: Ukrainian) should have at least one book or edition published by Orenstein in their book collection. In a way, this indicates an educational and cultural level if you are a book-loving person. Orenstein was a great representative of the reading nation, and we will mark the 150th anniversary of his birth in 2025 in Kolomyia.

Orenstein's early career

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: What do we know about Orenstein's milieu? What could have influenced his choice to engage in publishing?

Ivan Monolatii: We have scant data on Orenstein's childhood and young years that would be confirmed by archival documents. We do know he was born in Kolomyia on 25 February 1875 in a family of Jewish booksellers. Researchers, indirect sources, and memoirs of various people involved in publishing agree on this point. His father, Saul, found himself in Kolomyia at one point and started selling various books in different languages. Interestingly, Ivan Franko bought a book on the 1848–49 Spring of Nations in Kolomyia from Orenstein's father.

We can also say with certainty that Orenstein's father had a small bookstore in the center of Kolomyia, where he sold books and office supplies. As is typical of Jewish tradition, the father passed his book-trading experience on to his son.

Yakiv Orenstein's mother was a native of Kuty in what is now the Ivano-Frankivsk region. Yakiv had multiple siblings, but many of them died of infectious diseases, as attested by archival documents in Warsaw's Archive of Ancient Acts.

The challenge researchers have faced for 30 years now is establishing what education Orenstein received and where. No documents have been found so far, but he was most likely a graduate of the Kolomyia Gymnasium.

Nor do we know about his professional education. Whether he received it in Lviv or Vienna, as was suggested by one researcher, there is no documentary evidence whatsoever. At one point, the young Orenstein found himself in Rzeszów in Poland, where he met his future wife Khaya-Rosa. He lived there with his wife's family after serving in the Austro-Hungarian army, like many Galician Jews. The young couple returned to Kolomyia sometime later.

According to one account, Orenstein received money from the Kolomyia Jews to launch his publishing career. Indeed, his first published items, mainly postcards, were produced in collaboration with a Kolomyia Jew. With time, Orenstein established himself professionally and financially and began publishing independently.

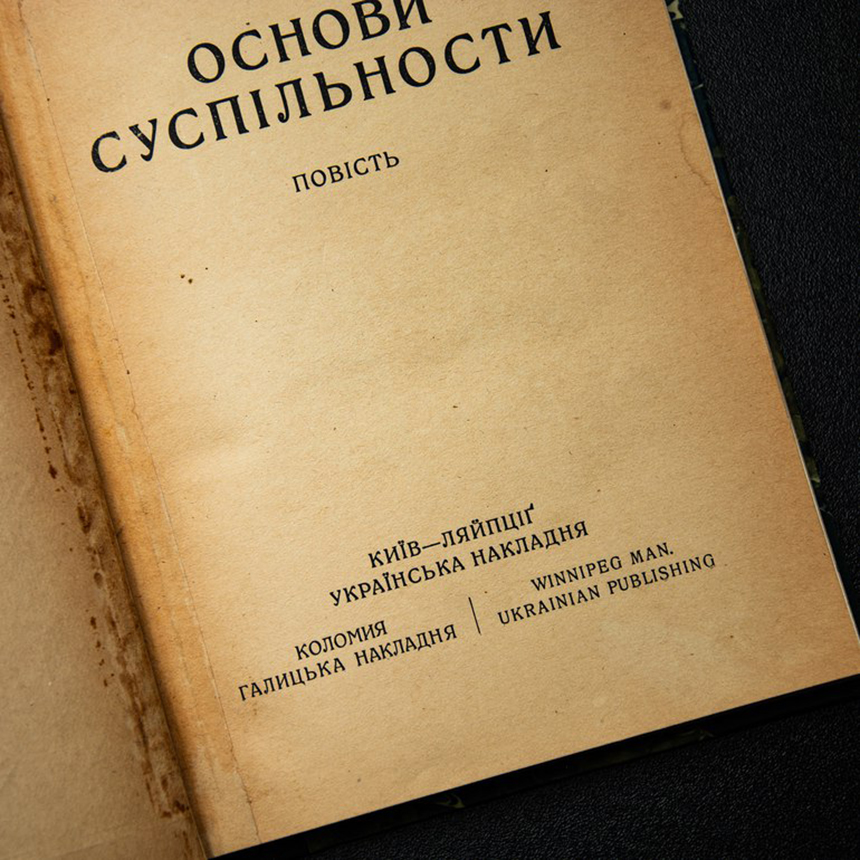

We still do not know when Orenstein launched his Halytska Nakladnia publishing brand and whether it operated within the borders of Galicia or across Austria-Hungary. Later, in emigration, he set up the Ukrainska Nakladnia publishing house.

Orenstein pursued, we might say, a symbolic idea of national unity as he tried to unite Galicia and Dnieper Ukraine through common Ukrainian values and priorities. Financially, he was highly successful in implementing his Ukrainian project.

Orenstein after the First World War

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: What happened to Orenstein in the 1930s?

Ivan Monolatii: Let me start with the First World War. In 1917, the Russian army looted Orenstein's house, bookstore, and storage facility for books in Kolomyia. He sent a complaint to the Provisional Government in Petrograd and claimed to have sent a similar one to the American President Woodrow Wilson. I have researched this issue but have not found these documents.

Even under these conditions, Orenstein tried to lead the Jewish community in Kolomyia in April 1917. He submitted a request to the Russian temporary occupation administration, saying that he wanted to run for the chief post of this community. He failed. In July 1917, likely disappointed and reduced to modest means due to financial struggles, Orenstein left Kolomyia. According to eyewitness accounts, he stayed in Vienna for a long time and then in Berlin before ending up in Kyiv in April 1918.

Orenstein came to Kyiv during the rule of Hetman Pavlo Skoropadsky and was issued the relevant documents to represent the Ministry of Education of the Ukrainian state on trips to Europe, primarily Western Europe. He promoted the Ukrainian cause and statehood as a publisher. A unique document from that period that includes a photo of Orenstein, quite advanced in years, is now kept in the State Archives of the Ivano-Frankivsk region.

Orenstein began studying the publishing market, primarily in Germany. He actively traveled to Berlin, Leipzig, Frankfurt am Main, and Nuremberg, looking for printers with Slavic roots to print Ukrainian-language literature. This is when he purchased military aircraft for the air fleet of the Ukrainian People's Republic. Unfortunately, these planes never reached Ukraine but were destroyed in the context of reparations from post-war Germany.

In 1920, Orenstein was given part of the premises in the embassy of the Ukrainian National Republic in Berlin to set up a Ukrainian publishing house, which he soon called "Ukrainska Nakladnia." We have documents showing that he and his business partner registered this new publishing brand in October 1920 in Berlin.

Orenstein did not limit himself to Europe. He made some extremely interesting trips across the ocean, mainly to Canada and the US. On visits to Winnipeg and then New York, Orenstein met Ukrainian publishers, librarians, and book experts. He offered them a large volume of the literature he published in Kolomyia before the First World War and his Kyiv-Leipzig publications, starting from 1918. Taras Shevchenko and Ivan Franko topped the list of Ukrainian authors for Orenstein. In particular, he launched a five-volume edition of Shevchenko's works.

Orenshtein's activities ruffled the feathers of political regimes that were not exactly sympathetic to the Ukrainian project. The Polish authorities actively monitored his publishing and political activities, sometimes even putting the publisher himself under surveillance. We have evidence that Orenstein tried in 1924 to join the well-known cause championed by Professor Roman Smal-Stotsky, who urged the authorities to allow a Ukrainian university in Galicia. Ukrainians had demanded a higher educational institution to satisfy their cultural and national needs since the time of Austria-Hungary, so this initiative quickly gained momentum but ended in an inevitable fiasco.

We also have evidence from that period that Orenstein contacted the UMO's leader Yevhen Konovalets in the so-called Romanisches Café, a popular meeting place for the bohemia in Berlin. Orenstein acted on behalf of international Jewish organizations as a mediator in the case of a UMO militant who was accused of an assassination attempt on the president of Poland.

However, these are all external things, and we know very little about Orenstein's private life during this period. Scant eyewitness accounts and letters preserved in Ukraine and abroad suggest that he and his family lived too modestly.

Orenstein tried to return to Kolomyia, and the local Polish administration was not against it. However, his social and political activities were a major irritant to the Polish authorities, which eventually denied his request. Thus, Orenstein went silent in our records from the mid-1920s until the mid-1930s when he was in Berlin. He joined the German Bookseller Union in Leipzig in 1934. However, Nazism was already on the rise in those days, and Orenstein must have seen where it was headed.

My research based on documents in the Federal Archives in Berlin shows that the Nazis soon launched what may be called culturicide against Orenstein in November 1935. He was constantly harassed, receiving letters from various Third Reich offices ordering him to shut down his business and telling him that, as a person of a different nationality (read: a Jew), he had nothing to do with civilization or any cultural activity.

Nonetheless, he wanted to sell his Ukrainian-language books and other products to athletes representing Soviet Ukraine and Polish-ruled Galicia at the infamous Berlin Olympics in 1936. It didn't work out for him, but his documents and correspondence with the Third Reich authorities have survived.

While the 1930s were a very sad page in Orenstein's life, the early 1940s were most tragic. He should be given credit for his tremendous desire to promote the Ukrainian cause worldwide. Orenstein sent out numerous letters and information bulletins on behalf of Ukrainska Nakladnia to Ukrainian bookstores and the Ukrainian diaspora. Sometime earlier, he seemed to try flirting with the Bolsheviks in Soviet Ukraine to get access to Kyiv bookstores but ultimately failed.

The Nazis forcefully liquidated Orenstein's publishing house. It took them two years to do so, from January 1937 until, most likely, January 1939. However, Orenstein got the better of them and arranged for the premises of his Ukrainska Nakladnia to be used by Ukrainians in Berlin.

According to documents, Ukrainians set up a civil and religious center in the building received from Orenstein. Greek Catholic priests and Metropolitan Andrej Sheptytsky himself could be seen as having a hand in this. In addition to the premises, Orenstein left an extensive book collection, which later, as Volodymyr Kubijovyč recalled, served as the basis for a network of Ukrainian libraries in Podlachia during the Second World War.

All in all, this is a very interesting story of how external forces hostile to the Ukrainian cause fought against Orenstein personally and his Ukrainska Nakladnia for at least 20 years. It seems to have been a rule, rather than an exception, of the historical period in which he lived.

Orenstein's motivation for championing the Ukrainian cause

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: Why did Orenstein promote the Ukrainian project? Do we know anything about this from, perhaps, his private correspondence? He kept coming back from abroad despite the war clouds gathering over Ukraine.

Ivan Monolatii: From what researchers know today, it was primarily his conscious choice in favor of the Ukrainian project. Jews traditionally revere books, and Orenstein intended the books he published to become a mass source and means of enlightenment. His two publishing brands are a testament to his desire as a publisher to enlighten first Galicians and then all Ukrainians. He had many allies in these efforts, particularly among the Galician intelligentsia, such as Bohdan Lepky and educators in Kolomyia, with whom he actively communicated.

Orenstein was placed next to, say, the antisemite Żyborski, who sold Polish-language publications in Kolomyia. However, it never came to any open conflicts. Everyone knew there was Orenstein's Ukrainian bookstore and the antisemitic bookstore run by the Pole Żyborski in downtown Kolomyia. This was probably why Orenstein was perceived as being hostile to the Poles, the second historical people of Galicia. This perception led to investigations, surveillance by the Polish police, and summons to the voivodeship authorities for testimony, even though Orenstein called himself "a Polish publisher of Jewish descent."

Still, we know that Orenstein's heart belonged more to Ukraine. He deserves to be remembered by both Ukrainians and Jews.

This program is created with the support of Ukrainian Jewish Encounter (UJE), a Canadian charitable non-profit organization.

Originally appeared in Ukrainian (Hromadske Radio podcast) here.

This transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

Translated from the Ukrainian by Vasyl Starko.

NOTE: UJE does not necessarily endorse opinions expressed in articles and other materials published on its website and social media pages. Such materials are posted to promote discussion related to Ukrainian-Jewish interactions and relations. The website and social media pages will be places of information that reflect varied viewpoints.