History of the word "zhyd" in Ukraine: From widespread use to marginalization

Serhiy Hirik, lecturer in Jewish studies at the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy, discusses the history and marginalization of the word zhyd.

Etymology of zhyd

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: I have recently overheard a conversation in which Jews were constantly referred to as zhydy [a disparaging word for Jews in Ukrainian. — Transl.]. This triggered a whirlwind of emotions, so I decided to discuss the issue and the origin of this word on air. Where did it come from? Is it offensive or not, and for whom? When did it acquire its negative connotations? My guest in the studio is the historian Serhiy Hirik who teaches at the MA program in Jewish Studies at the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy.

So, how can we explain the term zhyd and its origin? Where did it come from? Do we know when it came into use in Ukraine's territory? Is it also used elsewhere?

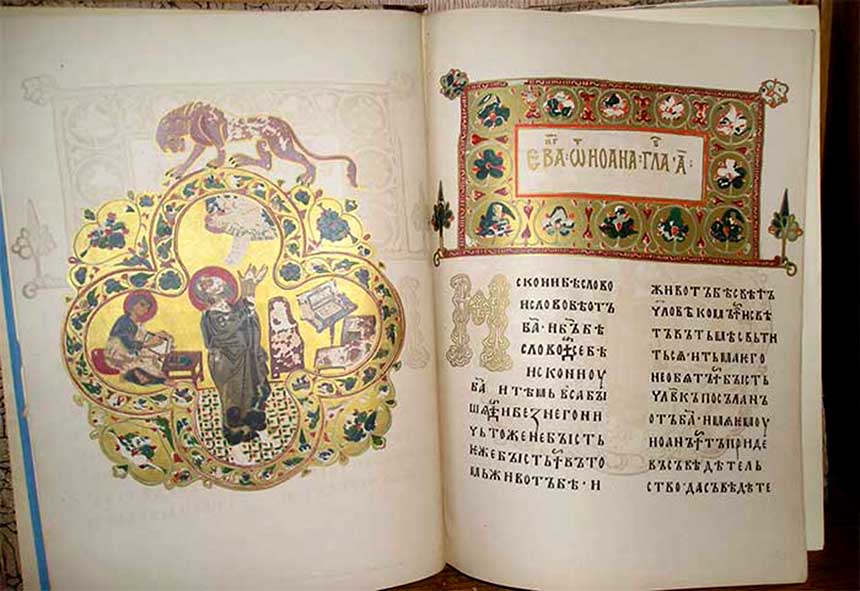

Serhiy Hirik: This is a linguistic question about etymology. In fact, the word zhyd as an ethnonym appeared and spread among the Slavs earlier than the ethnonym yevrei. Zhyd comes from the Latin word judeus, which referred to a resident of the Judea province of the Roman Empire, i.e., the former kingdom of Judea. The [j] sound became [zh] in many Romance languages. It came into the Slavic languages in this form from the Eastern Romance languages, those dialects of vulgar Latin that formed the basis of Modern Romanian. The transfer most likely occurred in the Proto-Slavic period because, as we can see, this word is present as the main designation of Jews in all — even West Slavic — languages. If it were present only in South and East Slavic languages, its origin could be sought in Old Slavic, the so-called Macedonian-Thessalonica dialect of Old Bulgarian. It was used as a language of religious worship and could give this word to the East and South Slavs. However, it is also present among the West Slavs. Thus, it was likely borrowed from the ancestors of modern Romanians back in the Proto-Slavic era, somewhere before the 6th–7th centuries. The oldest written record in the territory of Ukraine that contains this word is the Ostromir Gospels, which date back to the 1050s.

On the connotation of the word zhyd until the 15th century

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: What connotation did the word zhyd have in the 1050s? Do we have any information about this?

Serhiy Hirik: Obviously, it had no connotations. It was simply the main ethnonym for Jews. There were no other ethnonyms. This word appears later in the Kyivan and Galician-Volhynian chronicles, again without any connotations.

The Kyivan Chronicle mentions the first Jewish pogrom in Kyiv in 1113 but describes it in a detached and neutral way. Jews are designated as zhydy; the word yevrei did not exist in this part of the world at that time. The chronicle mentions that the death of Prince Sviatopolk Iziaslavych led to disorder and riots in Kyiv. The house of one military chief was looted, as were Jewish homes. A message was sent to Sviatopolk's successor: "Prince, come because after the Jews, they will start looting churches and then your property; it is better to avoid that." That is, judging by this entry in the chronicle, it was not a Jewish pogrom as a manifestation of some intolerance toward Jews. Rather, the rioters looted the property of the prince's representative and those they could get to, but they didn't reach the church.

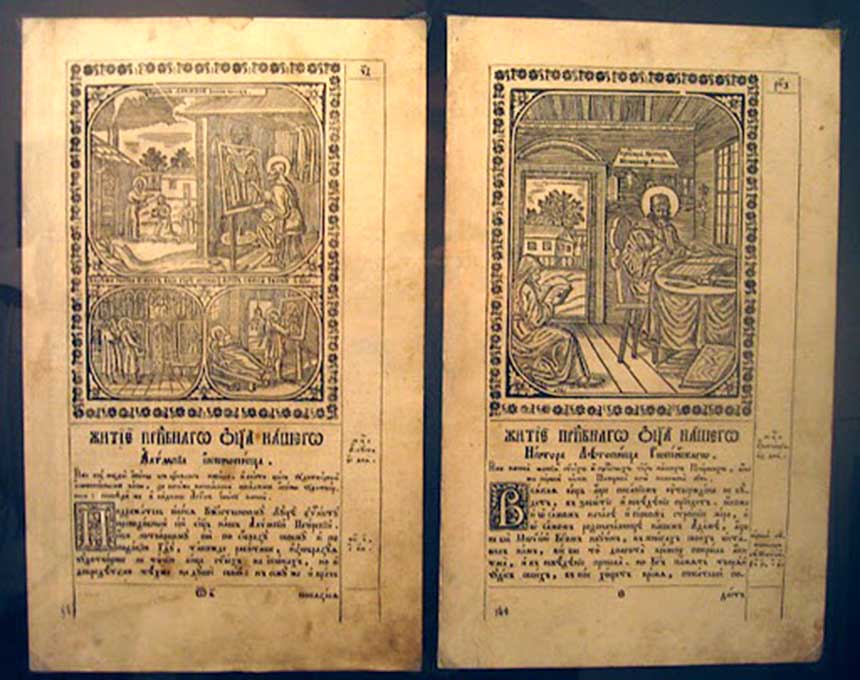

The oldest reference in which zhyd can be perceived to carry a negative connotation is the Kyiv Caves Patericon, more precisely, The Life of Theodosius.

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: When was it written?

Serhiy Hirik: Dating this text is a big open question. It is traditionally attributed to Nestor, and if so, it dates back to the late 11th century or the early 12th century. However, the oldest edition used when publishing The Life of Theodosius as part of the Kyiv Cave Patericon dates to the mid-15th century.

There is an episode in this work where Theodosius joins Kyivan Jews for a night debate to provoke them to kill him. This never happens, and he calmly discusses theological topics with them at night. It is unknown whether this passage appeared in the text as it was originally written or was added much later by editors and scribes. The oldest extant edition dates to the mid-15th century when zhyd definitely had a negative connotation.

The conditions of Jews in the 14th–15th centuries on the territory of Ukraine

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: What can we say in general about the conditions of Jews in the 14th-15th centuries in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania on the territory of what is now Ukraine? Were there any prejudiced attitudes at the level of Ukrainian society then?

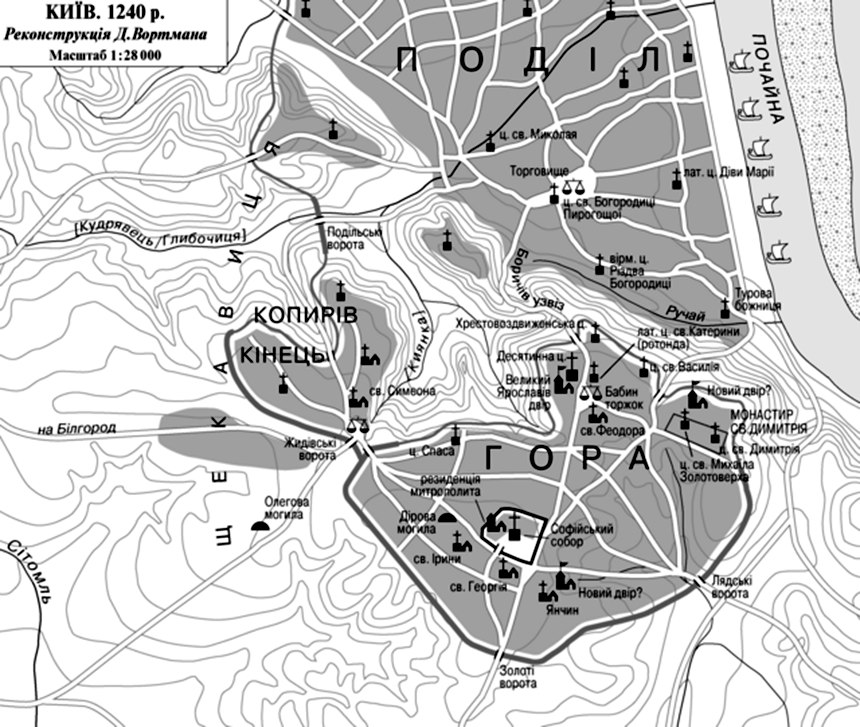

Serhiy Hirik: First of all, there were many more Jews. We know nothing about how the Old Rus' Jews disappeared. Those were different Jews. In the times of Rus', the so-called Slavic-speaking Jews, who spoke what is called Knaaniс, i.e. Slavic-Jewish dialects, were quite insignificant. The rest were Turkic-speaking Jews, but again, it is impossible to judge their numbers. We can only say there was a small Jewish quarter and the so-called Jewish Gate in Kyiv. But we don't know how many Jews lived there and whether they resided in other towns. Later, there were Jews in some cities of the western regions of what is now Ukraine, in Novgorod, etc. But there were very few of them.

During the time of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, Ashkenazi Jews migrated from Western Europe, specifically from the territory of modern Germany. They first moved to the Kingdom of Poland and then to the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Jews occupied a certain social niche, becoming an intermediary link between peasants and landowners. The duchy had a largely agrarian economy.

At the end of the 15th century, Jews were expelled from the Grand Duchy of Lithuania for a short while. After returning in the early 16th century, their numbers had dwindled to tens of thousands. Meanwhile, the territory of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania was vast, covering half of modern Ukraine, all of Belarus and Lithuania, and part of neighboring lands. Jews lived compactly in separate towns, i.e., most locals never saw them in their entire lives.

The Jews played the intermediary role between the Grand Duke as the largest landowner, the individual princes, and various other landowners on the one hand, and the peasants on their lands on the other. A negative attitude toward the Jews was formed over time as they were viewed as representatives of the authorities, those to whom peasants were obliged to give part of their produce. Understandably, this created social tension between the two groups, but we do not observe any significant manifestations of this tension in the first centuries.

Even the expulsion of the Jews from the Grand Duchy of Lithuania in 1495 on the initiative of Grand Duke Alexander Jagiellon was carried out primarily due to religious motives, as he was a very radical Catholic.

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: So, there was a religious factor there.

Serhiy Hirik: Religious Judeophobia definitely existed at that time. Specifically, if we talk about the Ukrainian lands, it was more pronounced than the manifestations of some social antisemitism. In contrast, both factors were present in Poland. But there were no violent anifestations, not even on a small scale.

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: Why was it so? Why was the religious factor present both in Ukraine and Poland, while the social factor only in Poland?

Serhiy Hirik: There were simply more Jews in Poland at that time: hundreds of thousands as compared to tens of thousands in Ukraine in the 14th century. So, the numbers and the intensity of contacts were different. Poland — the Kingdom of Poland, along with Galicia — was a much more urbanized country then. The rest of Ukraine's territory was in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania until the mid-16th century and was much less urbanized.

Even Kyiv, with its population of less than 50,000 people, was a small settlement at that time. A large village by modern standards, it was tentatively considered a city simply because it was the center of a distinct principality within the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Urban life and urban economy did not exist outside the boundaries of individual settlements then. Accordingly, there was no economic basis in these lands for the settlement of Jews, most of whom were engaged in trade.

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: How did the Jews live: separately or in their own districts, such as in Kyiv?

Serhiy Hirik: We do not have data on where they lived in Kyiv during this period. There is a record of the Jewish quarter in the 12th century. It's not clear how they settled during the time of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Moreover, after the Jews were driven out from the duchy and later allowed to return in the early 16th century, they did not come back specifically to Kyiv. The Jewish community was not revived until the 19th century there.

Other cities could have small Jewish quarters. But they were undistinguishable even visually in very small settlements representing literally just a few streets adjacent to others. Of course, for purely logistical reasons, it was more convenient to settle together: the Jewish community in one quarter, the German one in another, the Armenian one in the next one, and so on. We see this in the cities of Podolia and Volyn. Ethnic communities would settle near their religious buildings to be able to approach them more easily.

Jews in Eastern Europe after the 15th century

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: What happened after the 15th century? Did the negative connotation develop and spread more widely just as the number of Jews grew in Ukraine's territory?

Serhiy Hirik: The migration of Jews from the West to the East continued until the 17th century, until the Bohdan Khmelnytsky uprising. At the time, negative connotations indeed emerged in both Orthodox and Catholic preaching literature. However, there was no alternative term for Jews at that time. That is, the negative connotation was attached to the usual ethnonym used by the Jews themselves. When they did not speak Yiddish and switched to the language of the neighboring non-Jewish population in conversations, Jews also called themselves zhydy. There were simply no other words to designate them at that time.

This is exactly what we see in the Catholic preaching literature in Poland during the same period. Judeophobia was very widespread both in Orthodox and Catholic preaching literature, as well as in polemical literature in the territory of modern Ukraine. However, there were no alternative self-designations for Jews.

At the same time, we see that this word has preserved its strong negative connotations in the territory of modern Russia, where there were no Jews. There was religious Judeophobia there, and a very pronounced one at that, but it was directed against some abstract Jews.

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: How can this be explained?

Serhiy Hirik: I am not a specialist in the history of Russian Orthodoxy, but at that time, it was very exclusive rather than inclusive and extremely intolerant of others, especially coming from the West. Muslims were the only others who were tolerated as a result of geopolitical processes — the accession of the Astrakhan, Kazan, and Siberian khanates. They began to be tolerated after the incorporation of Muslim-populated lands. Those were the others that had to be put up with. It was necessary to accommodate others as the Muscovite Empire expanded.

Influence from the West was viewed as more dangerous, and the Jews were perceived as its component. The so-called "Judaizing heresy," widespread in the late Middle Ages in Novgorod, was still very much present in the minds of the people.

We have the fact that there was intolerance toward Jews in Russian Orthodoxy, even though there were no Jews in the Muscovite Empire. There were no living Jews against whom this intolerance could be directed. This had to do with the reason why the alternative ethnonym spread later.

How the word yevrei came to be used instead of zhyd in Ukraine

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: They say that the word zhyd was not an offensive one in the western part of modern Ukraine. For example, Jews in Lviv would use it to refer to themselves. Meanwhile, the situation in eastern Ukraine was different. How true is this statement? And are there any differences in how this word is used in various regions of Ukraine now?

Serhiy Hirik: It is better to talk about the past here. Indeed, older people in the western regions may not attach an offensive meaning to this word. But the person they talk with may perceive it as an insult. So, if they use it referring to a Jew, even without wanting to offend him or her, they will unwillingly sound offensive nonetheless.

This kind of regional difference existed in the past. Modern language constantly changes, and the difference that existed 100 years ago cannot be forced upon Modern Ukrainian.

Regarding eastern Ukraine and the Russian language, under whose influence the ethnonym yevrei has spread as the main one in Modern Ukrainian, we can look at the dynamics of changes in Russian and how it brought about changes in Ukrainian. If we open Karamzin's Letters of a Russian Traveler, there is an episode in Frankfurt when the narrator, Karamzin himself, talks with a local Jew. He writes with great sympathy about the Jews of Frankfurt, about Moses Mendelssohn, whom his interlocutor reads, and constantly uses the ethnonym zhyd. He simply does not know the word yevrei at this time, the late 1780s and the early 1790s, and writes with great sympathy toward the Jews. This happens immediately after the accession of most of Right-Bank Ukraine to the Russian Empire.

After Right-Bank Ukraine and the territory of modern Belarus were incorporated into the Russian Empire during the partitions of Poland, the Russian Empire suddenly acquired a significant Jewish population. And they were faced with the fact that the word zhyd had a negative connotation in the Orthodox tradition. This is when we see a certain change. The word zhyd was the only one used everywhere, both in secular and religious texts, until the word yevrei emerged in the Russian language as an alternative, non-offensive word at the end of the 18th century. At the same time, the word zhyd continued to be used sometimes in neutral contexts and sometimes as an offensive word in religious texts.

The word yevrei was finally fixed in normative legal acts and began to dominate in the Russian language in 1804 with the passage of "Regulations on Jews," a framework document regulating the rights and duties of Jews. While categorized as belonging to different strata in a stratified society, the Jews represented, in fact, a group that cut across those boundaries and had to be regulated by a separate act. And from that time on, we see the word yevrei being used in all documents, except for some of the decrees of the Holy Synod, achieving absolute dominance in the Russian language. During the 19th century, it gradually entered the Ukrainian language, but only in the lands under Russian rule. A well-known debate over the word zhyd emerged in 1861–1862 between the Odesa-based Sion journal and the Ukrainian Osnova journal. Osnova used this word as a neutral one.

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: Was it the time when Kostomarov defended the right to employ this word?

Serhiy Hirik: We don't know whether it was Kostomarov, as the answer to Veniamin Portugalov's letter came from Osnova's entire editorial staff. Portugalov was a doctor with a Jewish ethnic background who participated in revolutionary circles and was exiled to the Volga region. He was very sympathetic to the Ukrainian movement and read Osnova. This word grated his ear as it was used both in Ukrainian- and Russian-language articles. He wrote a letter and signed it with his initials. This letter was printed by Osnova along with the editorial response. We don't know who was the author. It could have been Kulish or Bilozersky. This was followed by a debate involving some figures from Osnova's circle and some contributors to Sion, except for Portugalov. However, the controversy was short-lived and ended just a few months later as both journals were closed in 1862.

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: To what extent did the intellectual and cultural milieu perceive these changes? You mentioned that the term yevrei was used in Ukraine's territory in the 19th century.

Serhiy Hirik: It was rarely used in Ukrainian-language texts in Ukraine's territory. The term zhyd was predominant until Jewish intellectuals became active in the Ukrainian movement, among other things. Until then, yevrei appeared only sporadically in Ukrainian texts in the Ukrainian provinces of the Russian Empire. We are not talking about Austria-Hungary, as the word yevrei did not exist there at all. There, zhyd was used regardless of the connotation; it was absolutely neutral there during this period.

Meanwhile, zhyd gradually acquired negative connotations in the Russian Empire and was replaced by yevrei, albeit very slowly. The change was finalized in the early 20th century. Notably, some of the Jewish activists who started writing in Ukrainian and cooperating with Ukrainian periodicals and some Ukrainian activists, tried to oppose this change then.

A very interesting story happened with the Rada newspaper, the first Ukrainian daily. On the initiative of Ahatanhel Krymsky and Yevhen Chykalenko, an attempt was made to reverse the connotations of these words and use yevrei in negative contexts to refer to Russified Jews who tried to distance themselves from the Jewish mass, were disengaged from the Jewish national movement, etc. They wanted to call such denationalized Jews yevrei. In contrast, when Jews were described positively, particularly the figures of the Jewish national movement, they would call them zhyd. However, there was no consensus on this reversal, even within Rada itself, and some contributors did just the opposite, employing the word yevrei in positive contexts.

Rada was a liberal newspaper and did not publish any antisemitic texts. Some of its authors were liberals, and some were socialists, but this newspaper never contained antisemitic texts.

The word zhyd finally marginalized

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: In Ukraine, we fight to remove ethnic slurs from use. Why did, then, the request of Jews themselves to be called yevrei rather than zhydy encounter such opposition?

Serhiy Hirik: People do not like to change and resist changing their habits. This is an inherent characteristic of many people. Indeed, we see that Jews asked Ukrainian intellectuals not to call them zhydy at a time when Ukrainian and Jewish national construction was taking place in the early 20th century. In fact, this was the reason for the final change in the 20th century.

Hrushevsky explained it very well in one of his articles during the Ukrainian Revolution, and it was nicely reflected in the documents of the Ukrainian People's Republic (UNR). At that time, there was a unit for Jewish Affairs [with zhyd used in its name. – Transl.] within the Secretariat for National Affairs, which was later turned into the Ministry of Jewish Affairs [with yevrei in its name. – Transl.]. Krymsky tried to counteract this trend in the 1920s when he was the permanent secretary of the Academy of Sciences. While he held this office, the Jewish Historical and Archaeological Commission published the first volume of its works and had zhyd in its name there. In contrast, the second volume, published one year later, already had yevrei in the commission's name. This was possible because Krymsky had been removed from the secretary's office in the Academy of Sciences. Despite this linguistic objection, Krymsky was actually a great Judeophile and did not hold any antisemitic views.

There was an ambiguous attitude even among Ukrainian intellectuals. Those who were more politically engaged were more likely to accept it. Thus, Hrushevsky, as a more politically sensitive individual than Krymsky, reacted to the Jewish request quickly and positively. He switched from zhyd to yevrei in his journalistic articles literally overnight. In the preface to one brochure, he wrote that he did not consider the word zhyd offensive but replaced it with yevrei and would continue using the latter, following the request of Jewish comrades in the Central Rada. He changed his linguistic habit overnight and stuck to it.

We later see that the word zhyd became marginalized and yevrei predominant in the UNR milieu, later in UNR emigration (with some exceptions), and in Soviet Ukraine (without exception). Meanwhile, the situation in Western Ukraine was quite the opposite.

There is a very clear parallel with the pair malorosy/khokhly [disparaging terms for Ukrainians. — Transl.] and ukraintsi [a neutral term for Ukrainians. — Transl.]. Those who drew this parallel changed their word usage regarding Jews faster, while those who failed to perceive it continued to employ zhyd. Meanwhile, this word became marginalized during the first decades of the 20th century.

This program is created with the support of Ukrainian Jewish Encounter (UJE), a Canadian charitable non-profit organization.

Originally appeared in Ukrainian (Hromadske Radio podcast) here.

This transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

Translated from the Ukrainian by Vasyl Starko.

NOTE: UJE does not necessarily endorse opinions expressed in articles and other materials published on its website and social media pages. Such materials are posted to promote discussion related to Ukrainian-Jewish interactions and relations. The website and social media pages will be places of information that reflect varied viewpoints.