How a Lviv footwear factory saved Jews from the Nazis

[Editor’s note: Below is an interview with Yuriy Skira, winner of Encounter: The Ukrainian-Jewish Literary Prize in 2024. The long list for the 2025 prize was announced last week. This year’s winner will be named at the Lviv BookForum in October.]

Historian Yuriy Skira discusses his book Solid about the eponymous Lviv footwear factory that saved Jews during World War II.

How Solid was researched and written

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: The guest of our studio today is Dr. Yuriy Skira, director of the Center for Research on the History of Eastern Catholic Churches and author of Beckoned: Studite Monks and the Holocaust and Solid. The Life-Saving Footwear Factory. The latter book won UJE's Encounter Prize in 2024. My congratulations to you!

I read the book with great interest and was surprised that the volume, encased in a high-quality cover, contained some 100 pages of main text, while the rest was filled with notes and appendices. I realized I was holding a scholarly monograph and wasn't quite sure what to expect. However, the book turned out to be highly readable despite the complexity of the topic itself. So, is it indeed an academic publication or, rather, an adapted version?

Yuriy Skira: I started writing Solid a few years ago. After completing my first book, Beckoned: Studite Monks and the Holocaust, published in 2019, I searched for a new research topic. I gradually came to the Solid factory, Rev. Josef Peters, Studite monks, and the people they sheltered. I immediately started writing it as an academic text and spent about 14 months working on it.

A lot of editorial work was done later. In fact, research continued until the last minute. I thought the text was finished more than once, but I was lucky to get my hands on new material each time. I stumbled upon some things on my own, while other materials were brought to my attention. After the book came out, I found even more materials. I have started putting them together to expand the text if it comes to a new edition within a couple of years. I think it is worthwhile.

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: The book describes how Jews were sheltered in a footwear factory near Rynok Square in downtown Lviv during the Holocaust. Why did you become interested in this topic, and how easy was it to research?

Yuriy Skira: My interest was kindled by the figure of Rev. Josef Peters. I became acquainted with him while writing my first book, Beckoned: Studite Monks and the Holocaust. I thought it was fascinating: the factory itself and the people working there. So, I started my research with Rev. Josef Peters.

In addition to Rev. Josef Peters, I have files on Lazarus (Shiyan), Theodosius (Tsybrivsky), and others. All of them were involved in sheltering and helping Jews. I had lots of information about them; other materials accumulated this way, and a monograph came out. Initially, there was a problem with sources: I had plenty of testimonies from the rescuers but very few from the rescued. At some point, the book's publication was in question because both sides had to be represented.

I was very fortunate to obtain from Yad Vashem the testimony of the Fink family (mother Faiga and daughter Anna) who hid in the factory in 1943–44. They left very vivid, extensive memoirs.

Their value lies not only in the description of the factory and what happened there. It is also valuable testimony about the fate of a child. What was the fate of a child who hides with Studite monks or nuns? What was her vision? What problems did she encounter? How was she treated by people around her (children, monks, and nuns)? I read it for about a month, a page a day. I had to analyze it myself and research the people and places mentioned in the text. It is an extremely powerful source.

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: Working on such a topic must have been difficult. How did you feel after completing the book?

Yuriy Skira: I love my work immensely. I love doing research, so when the monograph was finished, I felt nostalgic. You see, while working on the book, I tried to find sources, archival materials, and people, the descendants of those described in Solid. I am thrilled that I got to know the Hordynskys, the Kachmarskys, and their descendants, i.e., daughters in this case. I talked a lot with people who knew Rev. Josef Peters.

Unfortunately, I have not found the Finks as of today. I also hope to locate their descendants and learn about their lives after 1950, when they arrived in Israel. Overall, this research has brought me great scholarly pleasure.

An objective view of history

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: In your book, you mention not only Ukrainians who rescued Jews but also those who fulfilled orders and committed atrocities against them. Did your views change as you worked on the book? What do you think about this strange phenomenon when there is one nation and country and the same circumstances, but people make such drastically different choices? Ukrainian history seems to lack clarity on this topic, and it becomes an object of manipulation.

Yuriy Skira: You know, we, researchers, must look at the picture of the past as it was. We have to discern different strategies and choices people make. Accordingly, we must describe everything as it was — these choices or strategies — regardless of different aspects.

If we, for example, looked only at the stories of Jews being rescued, we would form a false, untrue idea about that period. Second, we would not understand the greatness of the rescuers. This is an extremely important point. Therefore, it is crucial to see the whole historical picture and different choices and to bring it to light in our research.

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: That is indeed true. At the same time, to what extent can such painstaking work and coverage protect us from highly manipulative discussions or even propaganda? I am surrounded by people who do not resort to manipulations, but when I leave this bubble, I am sometimes deeply hurt. And I start scolding myself for not doing enough as a journalist and the host of the Encounters program. Do you have similar emotions on a purely human level?

Yuriy Skira: If you are a historian, it is crucial to be ideology-free and discard all things ideological. As historians, we must act professionally and objectively. When we are on the path of objectivity, professionalism, and methodological understanding of the issue, all these things are not worth considering. We must simply do our job well and show the past as it was in all its different aspects.

Solid and Schindler's List

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: Have you thought about possible parallels with Schindler's List? Can they distance the audience from reading your book?

Yuriy Skira: I didn't just think about it. I made a point at the beginning of the book that such parallels could be made. However, Oskar Schindler ran a large factory, while Rev. Josef Peters managed a medium-sized enterprise. Most importantly, Schindler was a clear case of an entrepreneur, which the authorities understood. In contrast, Rev. Josef Peters did not reveal to the local authorities that he was a priest. The early spirit at his factory was also special. Many monks worked there, but some secular people were employed as well. Why?

The factory was operated to provide financial support to the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church. It was in poor condition after its membership was decimated and its property severely damaged in 1939–41.

Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church during World War II

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: How would you describe the general condition and standing of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church at that time? The figure of Andrey Sheptytsky is widely known even outside the Greek Catholic Church and among non-believers. We understand he was a colossal figure, but could you tell us more about him?

Yuriy Skira: The Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church was crippled after 1941. Like all of Galicia, it experienced a traumatic and terrible period in 1939–41, when its property was nationalized, and the German authorities never returned it, except for some things in cities. Many clergymen fled (a small proportion returned during the German occupation) or were exiled or killed. This was the face of Galicia at that time — highly traumatized.

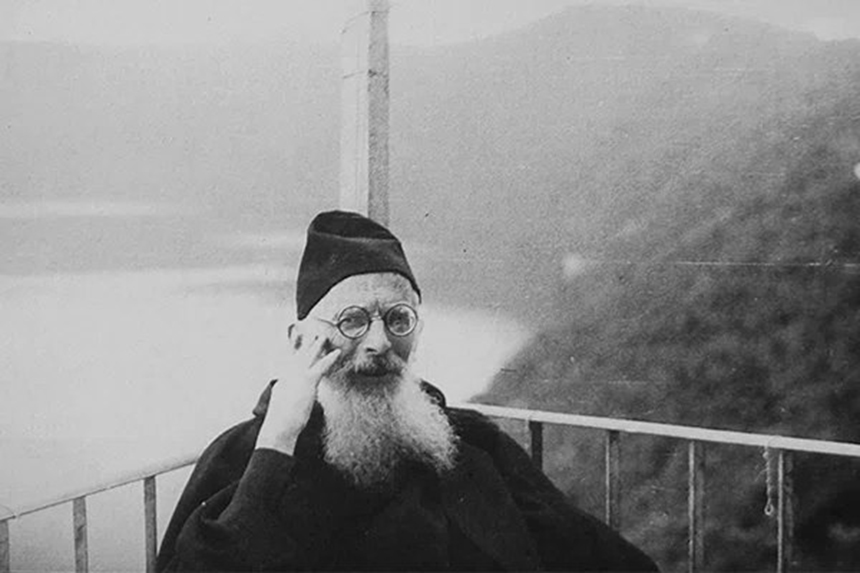

As far as Metropolitan Sheptytsky is concerned, he was an older man confined to a wheelchair at the time. However, he had set up an excellent communication network around himself. Even though he did not leave St. George's Cathedral and its surroundings, he was well-informed about what happened on the outside, which is truly amazing. Great people like him sometimes do not receive all the necessary information. However, Sheptytsky was different in that he was fully aware of the situation and reacted to unfolding events as the head of the church. He issued pastoral letters that the German authorities censored. Some were not allowed to be publicized, but he pressed on and tried to get them out.

When Sheptytsky saw that the situation was so critical — and it was indeed terrible — he began to rescue all the people who came to him. Let me emphasize this again: all the people. When a person knocked on the door, asking for help, their request was granted regardless of whether Sheptytsky and his entourage knew the person.

On the concept of a Judeo-Christian community

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: What do we know about Sheptytsky's idea to set up a Judeo-Christian community in Lviv? It did not come to fruition, but what was the concept?

Yuriy Skira: This was indeed a project Metropolitan Andrey Sheptytsky developed in the 1930s. But the year 1939, of course, made its implementation impossible. Some people wanted to belong to the Greek Catholic Church while preserving their national characteristics, etc. Sheptytsky became passionate about this project of creating a separate community. Rev. Ivan Kotiv, who was tapped to exercise spiritual care of this community, was a fascinating figure. Very close to Sheptytsky as one of his secretaries, he played a key role in the metropolitan's rescue campaign after 1942. Later, Kotiv traveled to Moscow to conduct negotiations under Metropolitan Josyf Slipyj and was so close to the Studite monks that he joined them at the end of his life.

Kotiv also knew Yiddish as he grew up surrounded by many Jews. So, Sheptytsky tasked him with the development of a Judeo-Christian community. It was supposed to adopt the liturgical practices of the Melkite Church, if I'm not mistaken.

This topic is underresearched, and the sources kept in Lviv's central historical archive and other archives are sufficient to produce a historical study if any scholars are interested.

Andrey Sheptytsky's brother and the rescue of Jews

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: What role did Andrey Sheptytsky's brother play in all this? He was also involved in the Solid factory, right?

Yuriy Skira: Indeed. Klymentiy Sheptytsky entered a Studite monastery in 1912 and actively helped his brother, Metropolitan Sheptytsky, after 1918, becoming inseparable from him after 1937 due to his brother's severe illness. Klymentiy handled relations with the changing authorities, church assignments, etc. In August 1942, he became a key coordinator of the Jew rescue campaign, caring for the men and boys Metropolitan Sheptytsky took under his wing. He sent them from the metropolitan's chambers to various hideouts. Many Jews he helped rescue (Kurt Levin, Mark Weintraub, and others) recorded a lot of memories about him.

Klementiy Sheptytsky responded extremely zealously to this calling of rescuing people. Mark Weintraub, who was sheltered in the cellars of the monastery on St. George's Hill in the summer of 1942, said that up to two dozen Jewish boys were in hiding there. According to Weintraub, Klementiy came to visit them every day and had a word for everyone. Weintraub says that in those terrible, inhuman, hellish conditions, he understood that there was humanity as he looked at and talked with Klementiy Sheptytsky.

Therefore, Klementiy Sheptytsky was not only an organizer but also a practitioner. He took extraordinary care of the Jews entrusted to him.

About a possible film adaption

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: Do you have any plans for a film adaptation? What do you think about this idea in general? I, for one, read the book thinking that it provided excellent material for a feature film.

Yuriy Skira: Every historian and researcher must have a big dream beyond all research, books, etc. My big dream is to have a film adaptation of Solid because it is so worth it. The story has multiple lines for a feature film, such as Rev. Josef Peters and other Studite monks who rescued people. It would make an excellent film depicting that period in all its complexity. It would offer a picture of Lviv during World War II, Studite monks, and Sheptytsky's entourage that carried out this great mission.

This program is created with the support of Ukrainian Jewish Encounter (UJE), a Canadian charitable non-profit organization.

Originally appeared in Ukrainian (Hromadske Radio podcast) here.

This transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

Translated from the Ukrainian by Vasyl Starko.

NOTE: UJE does not necessarily endorse opinions expressed in articles and other materials published on its website and social media pages. Such materials are posted to promote discussion related to Ukrainian-Jewish interactions and relations. The website and social media pages will be places of information that reflect varied viewpoints.