How and when did the first synagogues appear in Ukraine, and why is this an important aspect of Ukrainian history (Pt. 1)

[Editor's note: Russia's unprovoked and criminal war against Ukraine suspended the regular work of many organizations, reorienting their efforts. So it is with the Ukrainian Jewish Encounter. In the coming weeks, we will run interviews and articles done before the beginning of the war, which reflect the myriad of interests undertaken by Ukrainian journalists, scholars and writers.]

The unique structures of ancient synagogues are preserved in Ukraine to this day. How did their story begin?

We learned about the history of synagogues in Ukraine and this element of Ukrainian-Jewish architecture from Oksana Boiko, Candidate of Architectural Sciences, associate professor at the Department of Restoration of Architectural and Artistic Heritage (Lviv Polytechnic National University), and academic associate of the Ukrainian regional scientific and restoration institute Ukrzakhidproiektrestavratsiia.

Oksana Boiko is a researcher of architecture, particularly synagogue architecture. One of her studies, based on her dissertation, is entitled The Architecture of Masonry Synagogues in Right-Bank Ukraine, XVI–XX Centuries.

What is a synagogue, and what is its purpose?

Vasyl Shandro: Mrs. Boiko, I will ask you first to tell us what a synagogue is. What is the purpose of this building? Tell us about the terminology regarding the building. Are there parallel terms for the building? What is this sacred building that is called a synagogue?

Oksana Boiko: The term "synagogue" comes from the Greek language and means "place of assembly." As a rule, synagogues in Ukraine were called schools or temples (bozhnytsi). The Poles called them bożnice. Sometimes the word appeared in such forms as bizhnytsia, and in Transcarpathia, I heard the term buzhnia.

Is there a difference between the buildings themselves and their names? Not at all. A synagogue is an assembly building; at the same time, it is a sacred building where people pray. Why a place of assembly? Because people gathered there. Even churches were called synagogues, as attested by ancient documents.

In a synagogue, people gathered to pray together. It was where they studied and commented on the Holy Scriptures, that is, the Torah. This is the sacred text of Judaism or the Pentateuch of the Covenant, and they also read the Talmud. What is the Talmud? It is a codex of Jewish laws governing the life of the community. The Talmud was the basic book regulating all spheres of life of Jews in the Diaspora. In general, for Jews scattered throughout the world, the synagogue was above all an assembly building, where, in addition to religious services in Diaspora conditions, other spheres of Jewish life took place, even trials. That is why a synagogue has a prayer hall, where various areas of life were discussed. Ancient synagogues also held jails. Sometimes a synagogue was expanded by the addition of various outbuildings where people studied, or societies of artisans prayed. Thus, the entire life of the Jewish community was concentrated in the synagogue.

Vasyl Shandro: In other words, it is not just a place for religious services, for prayers, but also a place for discussing and approving decisions that are important to the community

Oksana Boiko: Synagogue and temple are equivalent terms given to buildings in our country where Jews gathered to pray and to resolve their various issues. Ukrainians called synagogues "schools" with good reason: because people studied there. Jews read and studied the Holy Scriptures, and they themselves called their synagogues shuls. There was a synagogue in Lviv that was called Hasidim Shul.

Vasyl Shandro: From shul? That's from the Yiddish?

Oksana Boiko: From the Yiddish — shul. Yiddish is based on the German language.

When and how did the first synagogues begin to appear in Ukraine?

Vasyl Shandro: What do we know about the first synagogues? When did they start being built on the territory of Ukraine, and where?

Oksana Boiko: We have few documents about the [Kyivan Rus] princely era, but it is clear that Jews lived here during the princely era, and they were governed by Rus′ Law. We have one mention from Kyiv, under the year 1113, stating that the Jewish Gate [Zhydivs′ki vorota] burned down. We know that in our country, Jews were called zhydy; today, they are called ievreï. But the former term is disappearing, and that is a shame. Fortunately, it has not been expunged yet from the works of Ivan Franko because it is a specific term for Ukrainians as well as all the other Slavic peoples. Poles use this term. I digress because I mentioned the Zhydivs′ki vorota. In ancient documents, communities are called iudeis′ki, Israelite; and their districts were called zhydivs′ki; on maps, the district is written as iudeis′ka, etc.

Therefore, the Jews in Ukraine first appeared during the princely era, and then they built their temples; but we do not have any information about them. The earliest information concerning synagogues appears in the fifteenth century; that is the earliest. They were already built in the fourteenth century, but we have little information, only brief mentions; for example, there was a synagogue in Lviv. But we have more information on the period when our lands, western Ukraine, ended up under Poland. There are archival materials and studies about this.

Regrettably, the stratum of this building culture has mostly perished. The oldest synagogues were wooden; they could be half-timbered. Obviously, they were impermanent because they often burned down. The oldest, partly intact synagogue — ruins — in our lands is the Golden Rose Synagogue in Lviv, which was built in 1582. So, we can speak about the earliest synagogue-building culture.

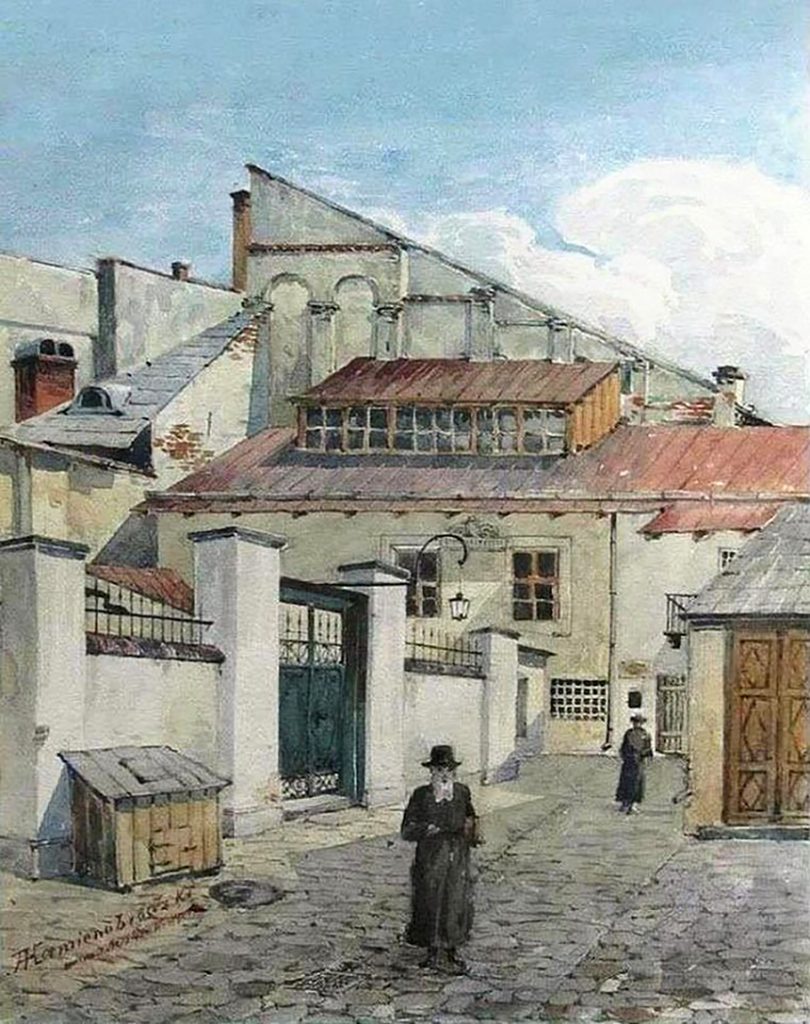

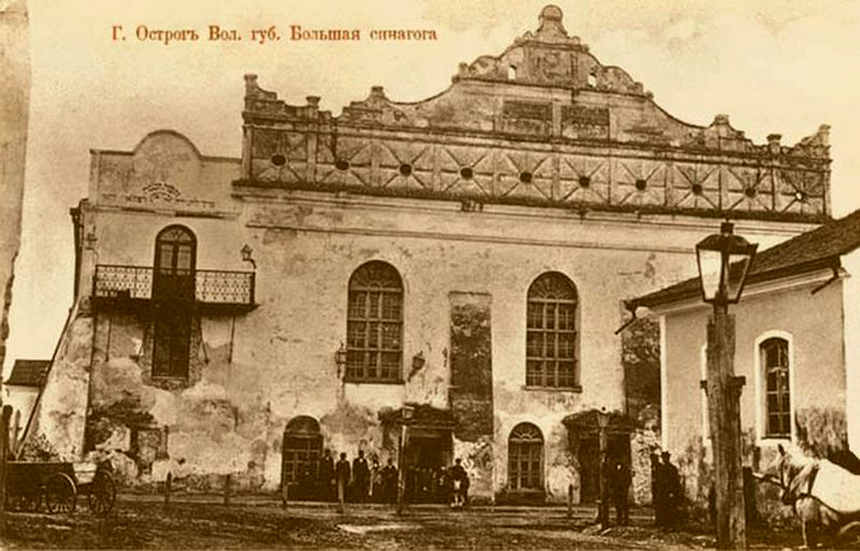

Some ancient, preserved synagogues in Ukraine are in Lutsk (1624), Pidhaitsi (1627), and Ostroh (1630). Later, in the eighteenth century, there are synagogues in Sharhorod and Husiatyn. In other words, quite a lot of old synagogues have been preserved in our country, in contrast to Western Europe, where there is a gap in the building culture between the fifteenth and nineteenth centuries

Vasyl Shandro: Because of policies?

Oksana Boiko: Yes, because the Jewish population was resettled, that is, it was expelled, and to a certain extent, this was connected with the formation and consolidation of Western states. Expulsions of Jews took place in Germany, Portugal, Spain, France, and Italy. Oddly enough, the Polish state offered Jews shelter, and they settled here, in our western Ukrainian lands. That is why by the late nineteenth century, one-third of all the Jews in the world lived in our lands.

Vasyl Shandro: This is truly an immense number. So can we say that the synagogue-building culture is a distinct stylistic phenomenon?

Oksana Boiko: Absolutely. Unfortunately, much has been lost, but at the same time, much has been preserved. Thus, we can trace the development of this construction. I am talking about masonry synagogues, because Jewish wooden architecture has not been preserved; that is a separate topic. There were far more wooden synagogues because they were cheaper to build.

Where were synagogues built, and what were the construction features?

It is worth mentioning where synagogues were built. Synagogues are an element of urban culture, urban architecture. And this is connected with the fact that Jews were mostly urbanites. Why? Because Jews were permitted to engage in trade and moneylending, and trade is the city. What is the city? The city means fairs and auctions. And when a city was being established, or it was developing, and privileges for fairs and auctions were being issued, the Jewish element appeared there. Once there were more of them, communities were formed, and the formed community had the right to establish a synagogue and a cemetery. These are the most indispensable elements of the functioning of a community.

Vasyl Shandro: Was it necessary to obtain permission to establish a synagogue and choose a site? Was it important who laid the first brick there? Was there a specific ritual involving the people who were supposed to launch the building of a synagogue, and how and in what place?

Oksana Boiko: Yes, obviously. The location of a synagogue was not accidental, and its selection was connected with the permission granted by the owner of the given city. A little bit of history is required here. All the ancient cities of western Ukraine were founded and developed according to the principles of Magdeburg Law, or the so-called German town law (I am talking about western Ukraine because I have studied it more). What does this mean? A city developed in keeping with city-building principles. Cities were either private and had owners, or they belonged to the king and had a governor. The essence of Magdeburg Law was self-government; cities evolved according to their own internal laws. At the request of an owner of a city, the king would grant such a right. Municipal self-government bodies headed by a mayor or reeve were introduced; they had their own courts — the administrative part. Along with Magdeburg Law, the king granted privileges for trade, and at that point, Jews would arrive in that city.

In western Ukraine, all cities and towns were also built in keeping with Magdeburg Law, that is, according to a certain urban system: A market square was built in the center, from the corners of which radiated streets with residential buildings, and all around, this city was more or less fortified. What did these fortifications look like? They varied, and that is a separate topic. But various communities lived in that city. In our case, in western Ukraine, cities were settled by Ukrainians/Ruthenians, Poles, and Jews — sometimes by Armenians in certain cities. And every community had a clearly designated spot for the construction of its temple.

Since this was the Polish period, a Roman Catholic church was built in the most prestigious place in the city: right in the corner of the market, this square area. Sometimes a city was established on some settlement where Ukrainians might already have their own church. The formed community of Jews also had a designated site for the construction of a synagogue. What does a formed community mean? It means that there had to be no fewer than ten people older than thirteen. As a rule, they were granted a spot at the back of the market quarter. Such were the times.

When you look at maps of cities and towns dating, say, to the mid-nineteenth century, you can see very clearly that a city — so regular, so clear-cut, built according to the principles of Magdeburg Law — has a neighborhood within the city limits that is built chaotically, with a big square in the center. That is the synagogue, and around it is a kind of "disorder," and this "disorder" is the Jewish quarters. Why this "disorder"? Jews lived according to their own laws, and they were not subordinated to the laws of the city, which is actually reflected very well on ancient maps.

The presence in the city of all these communities, mentioned earlier, shows the sacred space very clearly. When you look at a historic city, its space is accentuated by the sacred structures of all its communities. These are the domes of [Ukrainian] churches, the spires of Roman Catholic churches, and the cubes of synagogues. Some very fine exemplars have been preserved. In Lviv oblast, for example, there is a city called Uhniv, the smallest city in Ukraine. And this small city, oddly enough, has preserved all three sacred buildings: a cube-shaped synagogue, a church with nice, luxurious onion-like domes, and a Roman Catholic church with towers. Or Pidhaitsi, where you can also see the wonderful block of the synagogue. From a distance, when you are traveling to Buchach, the entire town opens up before you, along with a synagogue, a nice ancient Roman Catholic church with a tower, and a domed church.

This is the sacred space that is typical of western Ukrainian towns, where each community had its own place in the center of that municipal organism. And it was formed around sacred structures. It was the same in large cities, like Lviv, for example. In ancient times, all the communities were formed around their sacred structures.

Who had the right to build synagogues?

Vasyl Shandro: So there are ten people over the age of thirteen. They have the resources and permits, and they begin to construct a synagogue. Who could be the builder? I mean, could it have been a multicultural team of laborers? Could a synagogue be built by non-Jews or the reverse: Could Jewish builders construct a Roman Catholic or Orthodox church? In other words, were any special principles that are known — recorded — governing the way this was supposed to take place?

Oksana Boiko: Absolutely. A very good question. They were built by the communities themselves, by affluent members of the community. They were often also built by a city owner, like Mikołaj Potocki of Buchach, who was a patron of the temples of all the communities. Sometimes the king himself helped out, like Jan Sobieski in Zhovkva or Zolochiv. The merchant Isak Nachmanowicz built himself the Golden Rose Synagogue in Lviv. The builders of ancient synagogues were Christians, and only in exceptional circumstances — Jews. Why did Christians serve as builders? Because, as mentioned earlier, Jews are an urban element. In cities, we have auctions, and we have artisan guilds. Jews did not have the right to belong to building guilds. In other words, Jews were employed in moneylending and individual crafts, but they did not always belong to guilds. That is why they were called partachi (hucksters) — artisans who worked outside of guilds, although later Jews could be cobblers and tailors.

As for the builders-architects, we have the names of the builders who constructed well-known synagogues, and they were Christians. One iconic structure, for example, the Golden Rose Synagogue in Lviv, was built by the Italian architect Paweł Szczęśliwy, who constructed many beautiful buildings in Lviv. Another one, the suburban Lviv synagogue, which no longer exists, was built by Amvrosii Prykhylny. Incidentally, both Szczęśliwy and Prykhylny, as well as Giacomo Madlena, who built the synagogue in Ostroh, or Petro Beber, who built the synagogue in Zhovkva, or [Andreas] Bononi, who built the synagogue in Peremyshl — all of them were natives of Italy. In our country, the builders were Italians from northern Italy. They were called comaschi [natives of Como, in northern Italy's Lombardy region — Trans.], or they were Lombards from southern Switzerland. The builders-architects of ancient synagogues were Christians.

In subsequent periods, during the existence of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, after the Compromise of 1867, when all peoples obtained preferences and the ghetto was destroyed, Jews could be builders of synagogues and other structures.

Decorated synagogues

Vasyl Shandro: And now about interior decorations. Where synagogues are concerned, are we talking about treasures? Because when we talk about Roman Catholic or Orthodox churches, there is often a lot of gold and diamonds; it's very elegant. Are murals or expensive utensils integral elements of synagogues?

Oksana Boiko: It is very interesting that in ancient times the outside of a synagogue, its exterior, was not sumptuous; rather, it was ascetic, and all the attention was concentrated on interior decorations. Just like inside Christian churches, a lot of attention was paid to the interior décor of the temple: carvings, murals, and trappings. There were many silver or copper candelabras with sumptuous engravings. Synagogues were opulent buildings, and their interiors were remarkably splendid. Special attention should be paid to murals because the walls and vaults of both wooden and masonry synagogues were covered with woven tapestries; they were substantial and extraordinary. There were no human figures in synagogue murals; people were not depicted because this was forbidden. But there were many Hebrew texts and symbolic images: many symbolic animals, including the mandatory eagle, ox, lion, or other beasts and birds. Signs of the zodiac were traditional. Symbols of the twelve tribes of Israel were also depicted. Musical instruments were a very popular subject of synagogue murals. These musical instruments were sometimes hung from trees. There were also subjects featuring the Temple in Jerusalem or those generally associated with the city of Jerusalem.

Synagogue murals were remarkable, but at the same time, they were canonical, so to speak. They passed from one period to another. Whereas the architecture changed in terms of style, interiors were conservative; that is, these murals depended on the hand of the master who created them. There is a synagogue with extraordinary murals in the town of Novoselytsia, in Bukovyna, which have miraculously survived. They were whitewashed because, during the Soviet period, that synagogue housed a Pioneer building. In 2008, when the owner began to do some work there, the whitewash crumbled, revealing magnificent murals featuring all those at times naïve art elements that were mentioned earlier: the signs of the zodiac, or many different animals symbolizing something. For example, there is one very moving subject: a little donkey is carrying spread-out Torahs, and it is painted in a very naïve and touching fashion.

This program is created with the support of Ukrainian Jewish Encounter (UJE), a Canadian charitable non-profit organization.

Originally appeared in Ukrainian (Hromadske Radio podcast) here.

Translated from the Ukrainian by Marta D. Olynyk.

Edited by Peter Bejger.

NOTE: UJE does not necessarily endorse opinions expressed in articles and other materials published on its website and social media pages. Such materials are posted to promote discussion related to Ukrainian-Jewish interactions and relations. The website and social media pages will be places of information that reflect varied viewpoints.