How did Belz turn into a “city of newcomers”? The story of the ruins of a frontier town

The regional historian Lyubov Khomyn talks about Belz Hasidism, the central square, and the town’s Jewish history.

Andriy Kobalia: This city is located three kilometers from the Polish border. In his research the historian Janusz Tazbir mentions Belz as one of the fortifications of the “Cherven fortified towns.” This group of cities situated on the border of Kyivan Rus′ and Poland probably arose in the tenth century. Most of these “fortified cities” have turned into large villages or are completely uninhabited. Today Belz, once a mighty principality, is a small city with a population of no more than two thousand people. Cobblestones peek out from holes in the asphalt, there are old buildings everywhere—the town has become a preserve.

The first written mention of Belz appears in Povist mynulykh lit [Tale of Bygone Years], in which the entry for the year 1030 mentions that Yaroslav Mudryi took the city from the Poles. Later it became part of the Galician-Volhynian Principality, and when the struggle for succession began, Belz was captured by the Lithuanians, Hungarians, and Poles. Ultimately, the Poles annexed the city to their state, where it remained for several centuries. Then Belz began to be transformed into a multicultural city. Besides Poles and Ukrainians, another people settled in Belz voivodeship. Lyubov Khomyn, senior scholarly associate of Belz Museum, recounts how this Ruthenian city within the Polish state became a Jewish center.

Lyubov Khomyn: We are talking about the fifteenth century. The first mention of Jews in Belz dates to 1469. Later they were allowed to settle in the “Lublin suburb,” where they built a wooden synagogue and a cemetery.

Andriy Kobalia: Who allowed this? In other words, this was a separate Jewish quarter?

Lyubov Khomyn: Every medieval city was divided into several sections: a citadel, a center, and a suburb. That is what happened in our city, too. Our citadel was called “Zamochok” [Little Castle], because there was a prince’s castle there. Then there was a tradesman and trading part of the city in the center. All around were several suburbs, including “Lublin.” That’s where the Polish king allowed the Jewish community to live. There was a list of cities that obtained the right. Among them was Belz.

Andriy Kobalia: These were Jews who had moved from other territories?

Lyubov Khomyn: Yes, they were Jews who were fleeing Western Europe because they were being persecuted by the Inquisition. When the community numbered at least ten people, a wooden synagogue and a cemetery were established. Eventually their number grew. The community engaged in the traditional Jewish occupation—trading. In the following years the Jews began to purchase plots of land from Ukrainian and Polish city residents. They did this because they wanted to live closer to the center, to the square where trading took place every day and fairs—several times a year.

Andriy Kobalia: What percentage of the city population was formed by Jews? Are there sources on the number of Jews and their share of the population of Belz?

Lyubov Khomyn: With every passing century their number increased. For example, before the Second World War in the 1930s they comprised two-thirds of the population. The other third consisted of Ukrainians and Poles.

Andriy Kobalia: In other words, Belz was almost an entirely Jewish city.

Lyubov Khomyn: Practically. To many people of the time it was known as a Jewish city. We cannot say anything about the Jewish quarters because the city itself was not that big. The swamps and forests did not allow for the expansion of Belz’s territory.

Andriy Kobalia: When you walk along the streets of Belz, sooner or later you reach the square. Judging by old photographs, it has not changed much. There are several buildings in which small shops are located, just like a hundred years ago. Lyubov Khomyn talked about who built the square.

Lyubov Khomyn: Around our square arose “small parcels” (plots of land), where a small building would be erected. On the first floor Jews would set up a workshop or a small shop. Living quarters were on the second floor, and in the back, in the yard, they had a small farmstead. This town is not big.

Andriy Kobalia: In other words, these were premises that in today’s parlance were quite utilitarian and multifunctional.

Lyubov Khomyn: Yes. A small shop was always located on the façade side, facing the square. That’s where fairs and markets took place. As is known, Jews lived quite comfortably here. We tried to determine whether the three ethnic communities lived in peace or whether there were conflicts. We didn’t find any. We uncovered only lawsuits.

Andriy Kobalia: Are these small buildings still standing?

Lyubov Khomyn: Yes, they were practically undamaged by the war. Right now, if you enter the square, you can see such two-story, long buildings with facades facing the square. The specific features of the ground here make it difficult to build more than two stories.

Andriy Kobalia: Was this multifunctional architecture characteristic of the Jews, or did the Poles and Ukrainians build the same thing?

Lyubov Khomyn: Polish and Ukrainian buildings were one-story with porches; they were a bit different. Of course, not all Jews lived on the square. It is not that big, and not all could afford it. Some also lived in one-story buildings.

Andriy Kobalia: What did they trade?

Lyubov Khomyn: They traded a variety of goods. For example, we had bakeries where “kreizyks” were made; the name comes from the baker’s surname. Local residents who had a chance to try them said that these buns were very tasty.

Andriy Kobalia: You said that there were lawsuits. I recall the case of Stanyslaviv (today Ivano-Frankivsk), where in the early twentieth century Ukrainians tried to occupy economic niches, but in the city the Jews and Poles had engaged in trading for centuries. Economic competition arose among the Ukrainians, Poles, and Jews. The conflicts were on the paper level. Who sued whom in Belz?

Lyubov Khomyn: The lawsuits were mostly about land and boundaries. There were no big conflicts in questions of trade.

Andriy Kobalia: In the eighteenth century a new religious branch of Judaism—Hasidism—spread among the Jews of Western Ukraine and later to other lands. In Ukraine, these teachings are associated mostly with Uman, as the holy Rabbi Nakhman of Bratslav is buried there. However, there is another center of Orthodox teachings in Ukraine. Lyubov Khomyn explained why once a year there are more visitors to the city than local residents.

Lyubov Khomyn: The Hasids— the women’s community and the men’s—come to Belz separately. Orthodox Jews will not go on excursions in mixed groups, even if it is a single family. In their tradition there is great respect for women, but according to their canons, a woman should be at home and take care of her husband, children, and the household, and carry out all the husband’s instructions. And he must support her.

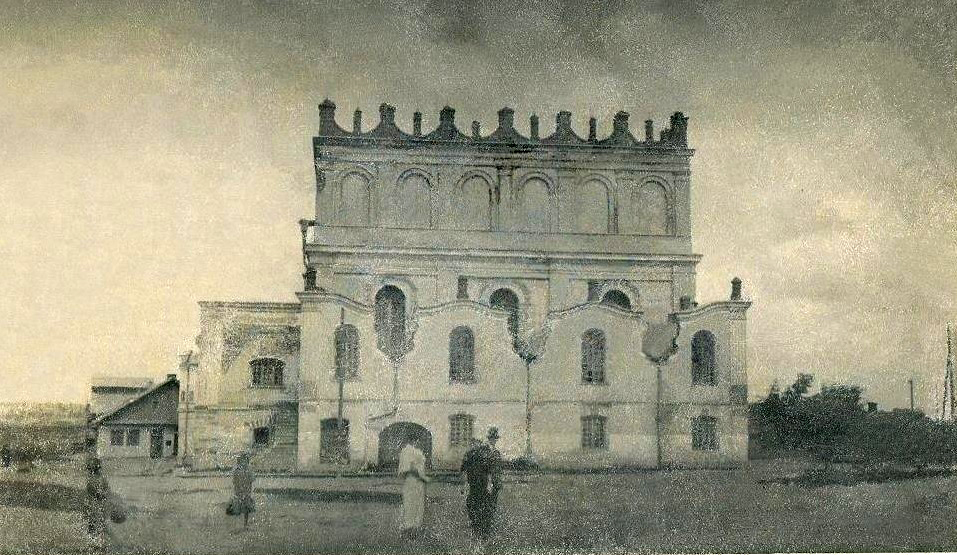

In the nineteenth century the Rokeach Hasidic dynasty appeared in the city. Its representatives were highly respected in the city, and not just by Jews but also by Ukrainians and Poles. The rabbis of this dynasty gave advice throughout the city. Shalom Rokeach founded the Belz Great Synagogue with his own money and funds from the community. It was similar to the one in Zhovkva. Along with it they built an entire complex, with a school, and the rabbi’s palace, which remained standing until the mid-twentieth century.

Andriy Kobalia: You are talking about an entire complex. Where can one find these small fragments of Jewish history today?

Lyubov Khomyn: There are no traces left of the Great Synagogue. Its destruction began during the years of the Fascist occupation. And in the 1950s the site was cleaned up, and a school was built there. That’s why right now on the site of the synagogue there are a workshop, a school, and a stadium. The ritual bathhouse remains only because there was a public bathhouse there. There is also a mikveh [ritual bath—Trans.] that was restored and renewed somewhat. A foundation was uncovered at the site of the synagogue; right now there is a commemorative marker there. This is where Jewish pilgrims come to pray.

The second important monument is the kirkurt, that is, a cemetery, where three rabbis who lived here and were tsadiks (holy men) are buried. This is a pilgrimage site.

Andriy Kobalia: Has the cemetery been preserved?

Lyubov Khomyn: Some matsevahs (matsevah: a Jewish gravestone in the form of a vertical stone slab—Ed.] have even survived. Right now there is a large, fenced-in field. Where the graves are cannot be seen, but individual matsevahs have been located. Now they are restored.

The third point is the building of the Ishre Lev Society dating to the beginning of the last century. The city was home to the lawyer Teofil Taube, who helped bring about the construction of the building. It was called “The Home of the Poor” because poor people and orphans were given assistance there. True, the building changed over the years, but the base remained. There are no other Jewish monuments. That is why the places of pilgrimage are the synagogue site and the grave of the tsadiks.

Andriy Kobalia: After the Second World War the city was annexed to Poland. But in 1951 Warsaw and Kyiv exchanged territories, and Belz became part of Lviv oblast. Lyubov Khomyn calls postwar Belz a “city of newcomers.” Only half-ruined architecture remains of old Belz. The Jews fled or were exterminated. The Poles moved together with the new border, and the local Ukrainians were displaced by the Polish authorities back in the 1940s. After all the perturbations, only two families moved back to Belz. The last representatives left or died in the 1990s.

In the 1930s in New York, a popular destination of the Jewish emigration, the composer Alexander Olshanetsky wrote a song called “Mayn Shtetele Belz.” It is not known whether the lyrics mention Ukrainian Belz or Moldovan Belzites, but the “small buildings” in the song recall those who surround the square in Belz.

Song about Belz 0:30-1:05

This program was made possible by the Canadian non-profit organization Ukrainian Jewish Encounter.

Originally appeared in Ukrainian (Hromadske Radio podcast) here.

Translated from the Ukrainian by Marta D. Olynyk.

Edited by Peter Bejger.

NOTE: UJE does not necessarily endorse opinions expressed in articles and other materials published on its website and social media pages. Such materials are posted to promote discussion related to Ukrainian-Jewish interactions and relations. The website and social media pages will be places of information that reflect varied viewpoints.