How did the Zionists live in Soviet Ukraine?

We are talking with the historian Viktor Husiev about Zionist parties in Soviet Ukraine during the 1920s.

The founder of Zionism, the Jewish movement for the creation of a state in the historical fatherland of Israel, was Theodor Herzl. In 1896, he published a book entitled The Jewish State, in which he laid out his vision of the future state. Over the next few years this idea spread throughout Europe. Even though Zionist organizations were banned in 1903 in the Russian Empire, to which the majority of the Ukrainian lands belonged, Zionist party centers appeared in many Ukrainian cities.

During the period of revolutions and wars, Zionist parties split and formed situational alliances with other parties in the empire, and when the Bolsheviks established their power, the majority of them became illegal. The historian Viktor Husiev, a professor of Kyiv Slavonic University who has devoted more than three decades to the study of Zionist parties in Ukraine, told us about the only legal Zionist party that existed in the Soviet Union in the 1920s.

Andriy Kobalia: When do the first Zionist parties appear in the Ukrainian lands?

Viktor Husiev: In the late nineteenth century two political currents emerged within the Jewish population, both of which participated actively in Jewish public life. This was a population of approximately five to six million people. The first political party was the General Union of Jewish Workers, known simply as the Bund. And that year, 1897, literally a few days later, another current emerged: political Zionism. Until the founding of other Jewish parties, these two dominated public life in the Jewish population. These parties represented Jewish interests, but the future was viewed in various ways. The Bundists were convinced that it was necessary to build a national life and a state in areas of compact habitation, including in Russia and Ukraine, while the Zionists thought it was necessary to restore Jewish statehood in Palestine.

Andriy Kobalia: If we are talking about the Ukrainian lands, where were these Zionist centers?

Viktor Husiev: The centers of the Zionist movement, like those of the Bundist movement, incidentally, were cities in which the Jews lived traditionally. Berdychiv was even called the second Jerusalem. Also, Zhytomyr, generally in the Volyn region, Odesa, Kherson, Mykolaiv, and generally the south—Katerynoslav [renamed Dnipro—Ed.], and a whole number of small towns. A network of Jewish settlements was located on Ukrainian territories; approximately two to two and a half million Jews lived here.

Andriy Kobalia: We are comparing the Bund and the Zionist movements. Were the former leftists and the latter rightists? After all, Zionism is described as Jewish nationalism.

Viktor Husiev: Some parties thought of themselves as socialist, and some—social democratic. Some added “Workers’” party. Yes, there was an element of nationalism in the Zionists’ actions because they were fighting for their own state. Where to build a state? They believed it should be where their history was, where they had lived for many centuries, where their culture had existed. The Bundists were leftists.

Andriy Kobalia: We recall that a revolution took place on the territory of the Russian Empire in 1917, and a Ukrainian revolution in our lands. Ultimately, the Bolsheviks seized the majority of the empire’s territories. The title of your paper at the conference “The Jews of Ukraine: The Revolution and Post Revolutionary Modernization,” which was organized by the Ukrainian Association for Jewish Studies at the National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy (NaUKMA), was “The Zionist Movement in Ukraine in the 1920s.” What was the Zionists’ experience of this period?

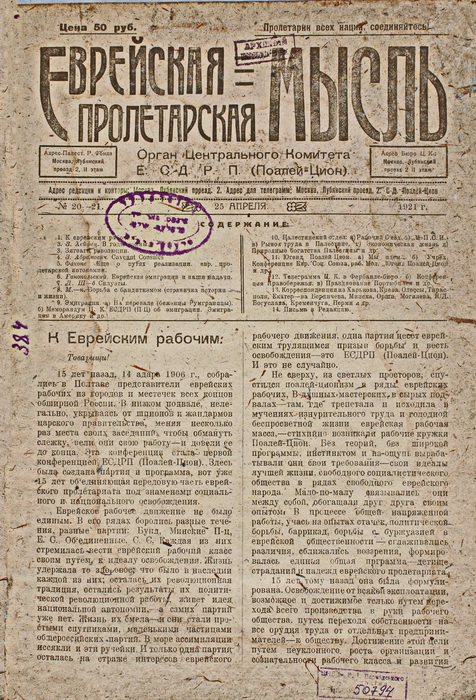

Viktor Husiev: Jewish political parties went through all these events with a sense of horror. I want to focus on the activities of the Jewish Social-Democratic Workers’ Party Po‘ale Tsiyon. Already under the Bolsheviks it was called the Jewish Communist Party Po‘ale Tsiyon. They are also called the YeKaPisty. It was the first of all Jewish parties and groupings to act practically legally, but could not evade persecution by the Soviet government. This party declared that the Jewish population could not expect assistance from the Soviet power.

What did the YeKaPisty, these practical individuals, propose? They prepared a memorandum, “To the Question of the Situation of the Jewish Masses in Ukraine through Immigration.” It was 1921. At the time, the Jewish population began immigrating all over the place—first and foremost to the United States—just so as not to remain in Soviet Russia. But the Soviet punitive organs managed to put a stop to the flight of Jews to the territory of adjacent countries. Jews generally had to overcome many obstacles in order to immigrate with their families. The YeKaPisty proposed the “sole plan for the reconstruction of the Jewish economic structure.” Who should lead? In their view, this was to be done by the All-Ukrainian Central Executive Committee. The committee was supposed to allow the Jewish community to create their national councils, and to enlist Jewish cooperation with Soviet self-ruling bodies.

Andriy Kobalia: Did the Soviet government pay any attention to this memorandum?

Viktor Husiev: It did, but that wasn’t enough. There were sufficient reasons for this. You know that during this period Ukraine was in a horrible state. But if the Soviet government had not looked with suspicion at foreign charitable organizations, it would have been possible to accomplish much more. As for cooperation, at the time the Soviet government consulted with the Jewish Communist Section of committees attached to the party of Ukraine.

Andriy Kobalia: Besides the YeKP [Jewish Communist Party], were there other parties? Did they operate illegally?

Viktor Husiev: Yes, the Zionist-Socialist Workers Party, the Zionist Workers Party, the Zionist Federalists. I would say that these are the three main Zionist parties that operated in the underground. Whereas the YeKP still worked somehow, these operated in clandestine conditions. And they were parties for the adult Jewish population. But there were also [parties] for young people, something along the lines of a Jewish Komsomol. There were organizations that worked with Jewish teenagers. The self-ruling bodies and the punitive organs had to combat these parties, for example, the OGPU, the Joint State Political Directorate, the future NKVD.

Andriy Kobalia: Let’s imagine that we are members of these parties. The entire country is controlled by the Bolsheviks, and law enforcement structures and services are everywhere. What were they reckoning on?

Viktor Husiev: In the annals of our Soviet archives is a document that was placed on the desk of Lazar Kaganovich, who at the time was, I think, the General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine. What troubled the Chekists? These parties were working deep in the underground, and they did not receive any outside help. Every year their activists were sent for re-education to Siberia, Kirgizstan, and Kazakhstan, yet the number of people in the ranks of these organizations increased. For example, this memorandum states the following: In 1924 there were 1,528 activists in underground parties, and in early 1924 there were more than 5,000. This is attested by that memorandum. It was stamped “Top Secret,” except not for Lazar Kaganovich and the members of the Politburo.

Where did the forces come from? The answer is simple. All the Soviet government’s measures that were supposed to create prosperity for the Jews (the next document in this connection appeared in 1925) were fiction. Imagine the classic Jewish town. Young people cannot earn even a scrap of bread there, let alone take an active part in socialist construction. Where do the young people turn their eyes? To whom will they listen? To the Zionists, who are operating underground. And those young people who could not extricate themselves from their small town enter the movement. The situation of shopkeepers and those who engaged in various types of cooperative ventures was difficult.

In 1921 the New Economic Policy, the NEP, was proclaimed. Yes, it raised the economic level in the country, but it also struck a severe blow at Jewish artisans and shopkeepers. How? The cooperative movement appeared in the countryside. Jews were accepted reluctantly into the cooperative movement. Businesses appeared that began to produce household goods which, thanks to mass production, cost less than those sold by a Jewish artisan. And all of a sudden, he’s without a job. Zionist propagandists appear unexpectedly. And they worked successfully in clandestine conditions. They had experience from the pre-revolutionary period. So, adults did not join the ranks of the Zionists, but they helped materially.

The points contained in the 1925 document state what must be done in the Jewish town in the field of medicine. It turned out that a single doctor without equipment and assistance has to accept up to 150 patients. Thirty to thirty-five percent of Jewish children could not attend school because they were not provided with the essentials. When a Jew went to a raion [district—Ed.] executive committee or a village soviet, he always sensed an undercurrent of antisemitism.

Andriy Kobalia: Why did the YeKP disappear, and where did all those underground parties go in the late 1920s, when Stalin came to power?

Viktor Husiev: The YeKP and the Jewish Section fought constantly with each other. There was no peace between them. As soon as the document appeared, it had to go through censorship in the local Jewish Section. And, like always, they were against what the YeKP proposed. That is why their time in Ukraine came to an end. The “elder” clandestine political parties and industrial organizations continued to operate. In 1930 a reorganization of internal bodies took place. The national sections were liquidated. In 1936–1938 former Jewish figures who had demonstrated humility vis-à-vis the Soviet order were also treated as enemies of the people. And if they survived, they ended up in the places that I mentioned earlier.

Andriy Kobalia: According to information contained in the State Archive of the Russian Federation, which the Russian historian Viktor Zemskov cites, in 1941 there were more than 30,000 Jews in the camps of the GULAG. Some participants of the Jewish political movement fled from the Soviet Union even before the Stalinist repressions. The rank-and-file party members could evade repressions if they completely repudiated political activity. Those who had lived through the 1930s and remained on the territory of Ukraine eventually witnessed the horrors of German occupation policies and, later, the postwar repressions, one episode of which was the so-called “Doctors’ Plot.” During the Thaw in the 1950s several waves of amnesties pertaining to Jews took place, but some of them became “repeaters,” that is, people who were sentenced a second time.

This program was made possible by the Canadian non-profit organization Ukrainian Jewish Encounter.

Originally appeared in Ukrainian (Hromadske Radio podcast) here.

Translated from the Ukrainian by Marta D. Olynyk.

Edited by Peter Bejger.

NOTE: UJE does not necessarily endorse opinions expressed in articles and other materials published on its website and social media pages. Such materials are posted to promote discussion related to Ukrainian-Jewish interactions and relations. The website and social media pages will be places of information that reflect varied viewpoints.