Iryna Slavinska: Welcome to the program “Encounters” on Hromadske Radio, supported by the Ukrainian Jewish Encounter. This fresh edition of the program “Encounters” is dedicated to the topic of Jewish silhouettes in modern Ukrainian literature.

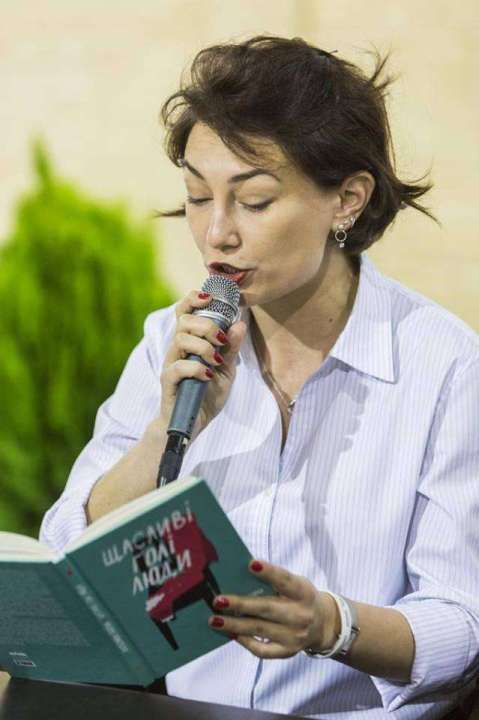

This talk took place during the international “Book Arsenal” festival in Kyiv. The writers Natalka Snyadanko, Larysa Denysenko, and Kateryna Babkina participated in this discussion, and Yurii Makarov was the moderator. Here are some excerpts from the discussion, and we start with Natalka Snyadanko, who discusses some of the blank pages of Ukrainian literature.

Natalka Snyadanko: I would like to focus my attention on the last phrase, about the figure of silence. When I was thinking about what we were going to talk about today, I had images from books appearing in my mind. They were not from Ukrainian books, by the way. As far as I am concerned, we have certain characters, situations, or stories, but we do not have these themes as such. We do not have the theme of trauma, historical context, or the theme of assimilation or its absence. We also do not have the theme of what is happening now, that is, the daily life of communal coexistence.

And when I was thinking about this, I thought about situations that are being kept quiet. There is for instance one of the not very many books available in Ukrainian, Martin Pollack’s text Contaminated Landscapes, that was recently translated by Nelya Vakhovska. This is not a literary text; it is more like a documentary or reportage. It is devoted to the massacre sites in Ukraine, mainly in Ukraine, but also in other countries of Eastern Europe. He travels to these places and always describes the similarities. Regardless of where it happens, it is always such a wasteland. He comes to a small town, and everyone knows where it was, and this is now some empty space, where there is nothing. There is no cemetery or memorial plaque, and no one dares, for example, to plant potatoes there. This is a place that everybody passes by and nobody will speak about it. For me, this is a very powerful and very good image, which shows how we approach this. It shows not even the literary attitude, but just our attitude as the residents of this territory.

The second thing I was thinking about is the novel by the German author Jenny Erpenbeck, who is almost not translated in our country. This is a novel about the history of a Jewish person that starts in Vienna and proceeds through Lviv, and goes far, far, far away. This is the history of the reconstruction of memory. At some point the character realizes that some generation is missing in the memory of her family. Fifty years of empty history, and nobody tells her what that history was. Obviously, this is the Jewish topic that is not being talked about. Then I remembered Joanna Bator’s book Sandy Mountain that I just recently translated. This is also the history of a reconstruction of a family; the story about the main character who discovers that she is the daughter of a Jew who was saved by her mother, and nobody in the family knows about it. This happened also very close to the Ukrainian border with a transition onward. This is a subject that I miss dearly in Ukrainian literature. I mean, this is all in these areas where we live, this is our history, this is what people remember, but it is not written in Ukraine. I fear even to think what may happen when it is finally written in Ukraine.

Here I am also remembering the comparatively fresh scandal around Olga Tokarczuk’s book. I am reading it now and I am trying to figure out the reason for that scandal. I do not know if you have heard about it. Last year this book received one of the biggest Polish literature awards, the “Nike,” and this book is about Halychyna [Galicia—Ed.]. This is a historical novel that takes place in the seventeenth century. There is a story about one of the Jewish sects there. This is very little known, and marginal history. It is an absolutely historical novel that provoked a flurry of hate. This hate was so intense that Tokarczuk was threatened personally. They called her a “Jewish rag” and “Ukrainian whore.”

Yurii Makarov: Who called her that?

Natalka Snyadanko: There was some movement online. Some individuals wrote to her Facebook page, and that really forced her to leave the country for some time. This is not a book that could offend anyone. This book does not touch any modern context, but it ruins the historical myth. There is no Poland in the way that Polish people imagine it. There is not an idyllic, great, and mono-ethnic Catholic country of sacrifice. This is Poland of the seventeenth century, where on the same territory live Polish Catholics, Polish Orthodox, Ukrainian Catholics, Ukrainian Orthodox, Turkish Muslims, and Jews, some of whom are Orthodox, Hasidic, Frankists, some are baptized, and they all live on a small piece of land. This story is really about tolerance, about the lack of tolerance, and about how we cannot co-exist. Iryna Slavinska: That was Natalka Snyadanko. And now let’s listen to Kateryna Babkina, who discusses Jewish themes in her work. Kateryna Babkina: In my novel Sonya there is a leading story line, and it is a storyline about a boy from Lublin—Genya Zhytomyrskii. A very interesting story. So in Lublin, in one of the Jewish quarters—they had even more of them than non-Jewish—there lived a boy named Genya Zhytomyrskii. He was from a good family, and it seems that his parents had a shop. As of 1943, Genya was eleven years old, and of course, we all know what happened to him. But what happened to the boy is understandable because some photographs and family archives were left and someone then found them somewhere. Also there was his children's journal, where he writes things that people who are ten and eleven years old write in journals.

I may be mistaken, but I think it was in 2004 when some good people—and I am not even sure that those good people were from Lublin—scanned his pictures, digitized his journals, and created a Facebook account for him, where they were posting his up-to-date journal entries. These entries are about the events he witnessed and about his everyday feelings, who he fell in love with, where he was going, who came to visit them, etc.

This journal was written for two years, as far as I remember. Genyo is on Facebook and he has lots of followers. That is how this story was brought back to remembrance. This boy was thus brought back to life in a way, and his story was told from his viewpoint. I think this was a pretty cool digital project, and maybe because it inspired me so much, this boy Genyo became the character of my book, and it is one of the main plot lines there.

The story is that the character comes to Lublin for Genyo’s birthday celebration, and sees the stencils with his children’s picture on the wall. There is a very well-known picture that was made before the beginning of all this hell that happened later on. The character sees all these portraits on the walls, and gets to know the story. She is pregnant and at some moment this Jewish boy comes to her and agrees with her that he will be the boy to whom she will give birth because he did not live his life to the end. He liked his life a lot, but not all the time because at the end of his life he was in for some difficult times. Thus he says: “I am feeling fine where I am right now, but I would like to come back.” She gives birth not to a Jewish boy, but to a girl, but that is a different story. Then this boy somehow appears later and his life story becomes through this Facebook story. I cannot say that people react positively or negatively to it. It is absolutely accepted as part of the text. I think the Jewish theme was only accented in one or two reviews.

Irinia Slavinska: And now we hear from Larysa Denysenko, who discusses her own literary work with this complex theme.

Larysa Denysenko: I was thinking that I have at least two books Sarabande of Sarah’s Gang and Echo) whose main characters are absolutely and clearly Jews. These Jews are modern Kyivans, and in Echo Jews in the period of the Second World War in Ukraine and not only there. Generally speaking, if we are talking about Ukrainian modern literature, there is Torhivnytsya by Ivanychuk, where there is a Galician Jewish context. There is also Tango of Death by Yuriy Vynnychuk and Freida by Maryna Hrymych, where she describes Berdychiv and the change of identity, because a Ukrainian woman finds diaries and she decides they are hers, but those diaries belonged to her Jewish childhood friend. This is very interesting and intriguing, and the spirit of Jewish Berdychiv is very well described.

I think our cultures are interrelated and today we, for instance, were talking during “The First Studio” with Marianna Kiyanovska and Borys Khersonskii. This is connected to what Yurii Makarov was saying about Jews in Ukrainian literature. We have the poets. Wonderful poets. Marianna Kiyanovska was discussing Khersonskii, who is a Russian-language poet in Ukraine.

Yurii Makarov: Borys Khersonskii also translates his poems into Ukrainian himself. Therefore, this is in some manner partially a part of Ukrainian literature because those are the author’s own translations.

Larysa Denysenko: The book that was published has Borys’s author translations and also Marianna Kiyanovska’s translations. She says that she came up with the Jewish-Ukrainian language for him to present the Odessa Jew. I think this is very important.

Coming back to my texts, for example, then I have Sarabande. This is satire, a family comedy, where there are two families, two outlooks…Of course, they are satirical because it is a comedy. There is a Jewish family and a Ukrainian family, and then a Jewish girls starts dating a Ukrainian boy, and these two family concepts are different. He thinks it is too loud and that there is too much attention because he is a very introverted individual and he does not like all of that. There are all these little humorous stories dealing the different family concepts.

Talking about a more serious approach, it would be Echo: My Life from the Dead to the Deceased Grandfather. I was trying to talk about reconciliation there, and this reconciliation is based on the examples of a German and Ukrainian-Jewish family. I have two main characters there: Marat whose last name is Hetman, and he gets this last name back because he needs to immigrate to Israel, but earlier the last name was changed to Het’man, and the family also wanted that change. This was a very painful topic in the 1970-80’s. The last names were changed so that children would not be bullied at schools.

Iryna Slavinska: Yurii Makarov now talks about the problems working with this theme—the historical events, the joint traumas, and also how one can work with the Jewish component in folklore that is present in many places like Lviv or Odessa.

Yurii Makarov: When we are talking about reconciliation or about solving the conflict (and the conflict of course exists, from one point of view, but from the another point we know it can be subject to some kind of manipulation), when historians start to research the Khmelnytskyi region, it turns out that the number of the victims can vary, but that does not mean that there were no victims. Excuse me, but whether it is one hundred thousand or ten thousand, ten thousand victims is nonetheless also frightening. If you come closer and closer to us, up to the Second World War, and then later to the hidden antisemitism of 1970’s, and then up to the end of the Soviet period, there is one scary thing. I remember from my youth that saying the word “Jew” out loud was a bit uncomfortable. It was not very comfortable at all. When I mention this today to the 21-year-old daughter of my friends, she does not understand me.

I think there are two sides of danger here. One of them is called, “So what, I also have Jewish friends.” This is the first side. The opposite is: “I do not know who is what nationality at all.” This is also not right. I always pay attention to whether a person is choleric or phlegmatic, if a woman is blonde or brunette. If a person is Bulgarian, Armenian, Azerbaijani, Jewish—for me it is always the fact of existence of some special experience that I do not have. I am not indifferent to this. On the contrary. And I care and I start to see if this person maybe knows something that I do not know. How do you think, without these anecdotal layers, without the trauma, if they no longer exist in today’s world, how is it possible to depict them?

Larysa Denysenko: I remember at school I was always called the “Baltic girl,” and “Baltic girl” is a very broad notion. I am Lithuanian on my mother’s side and they always copy our Russian: “We speeeeeeak veeeeery slooooow in Russssssian and we are all veeeeeeery sloooow!” This is in all the jokes. As a matter of fact, when I was following my mother’s accented Russian language, I spoke a bit slow. This does not exist now, but it exists in the jokes. I can laugh about it as much as any Jew can laugh at jokes about Jews. I never see it through the prism of hatred. If we are talking about modern Lithuania, especially about Russian-speaking Lithuania, one cannot hear such a strong slow accent there. It does not exist. This does not mean you cannot play with it though. You can and you should.

If you are talking about modern pieces, you know, I have not thought over the trauma. The common traumas of our two nations, the common historical and social traumas of the 1990’s or 1980’s, that is, from the Soviet Union, when they were not calling you a political dissident, but a hooligan, and were putting you in jail for at least three years only for the fact that you were trying to leave this country. We only have a memory about that.

Yurii Makarov: This is not some single case. It was a common practice.

Larysa Denysenko: This is only in the memories of Nelli Nemyrovska—the lawyer from Luhansk who very often defended dissidents, and not all of them were political dissidents. Absolutely not, they were people who just wanted freedom, who wanted to leave without the political component, but then they appeared in criminal proceedings.

Iryna Slavinska: You were listening to excerpts from a discussion on the Jewish silhouette in Ukrainian literature at the “Book Arsenal” festival in Kyiv. This discussion, and the program “Encounters,” was sponsored by the support of the Canadian philanthropic fund Ukrainian Jewish Encounter. Listen. Think.

Originally appeared in: http://hromadskeradio.org/programs/zustrichi/yevreyski-syluety-v-ukrayinskiy-literaturi

Translated by: Olesya Kravchuk, journalist, interpreter

Additional translation and editing by Peter Bejger