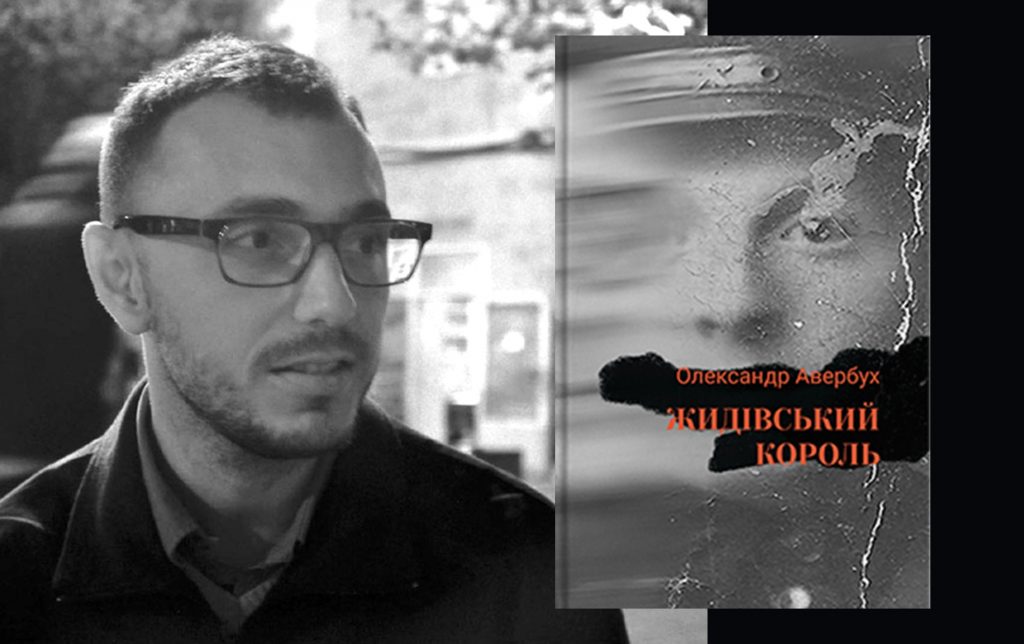

In history's embrace: Reflections on Alex Averbuch's book "The Jewish King"

In my view, Alex Averbuch's book Zhydivsky korol (Kyiv: Dukh i Litera, 2021) should be considered as a cultural fact of Ukrainian-Jewish relations. Interwoven into the poems in this volume are colorful threads from the histories of various peoples, like the many destinies of the poet himself. As the author says:

I forgave myself

for my Ukrainian great-grandfather who went on a pogrom against my Jewish great-grandfather

I forgave my Polish great-grandmother who tore off my Jewish great-grandmother's braids

I forgave myself for my Muscovite great-grandfather who took the last scrap from my Ukrainian great-grandmother

I forgave my Jewish great-grandmother who wrote a denunciation against my Ukrainian great-grandfather

It strikes me that the poet is not talking about literal kinship, about his obligatory presence amidst his ancestors, Ukrainians and Jews, Poles and Russians, even though these nationalities figure in his family tree. It is about the idea that today Ukrainians feel — or should feel — that the Russians, Poles, and Jews who inhabited Ukrainian territories are "their" people. In its history, Ukraine mixes and interweaves its inhabitants, even if sometimes posthumously.

1. The genealogy of the "Jewish king"

Alex Averbuch's poetry collection is divided into three sections: "The Last Supper of My Body"; "So I Will Never Forget about in Regard to You"; and "The First Impression of Nonexistence." Some cycles of poems were published earlier but are now the branches of a common literary tree.

"The Last Supper of My Body" is devoted to family history and poses the following cryptic question to the reader: What does the phrase "Jewish King" (Zhydivsky korol) signify? In the normative literary register, the expression "ancient king of Israel" would be appropriate but "Jewish king" would be impossible. At the same time, the pejorative "zhydivsky" has a diverse range of meanings, and denotes not only the abasement of Jews, but also their non-genuineness, their difference from the concept of "human." Thus, a "Jewish king" is a king contrariwise: without authority, without subjects, without a throne and crown. Yet, like all kings, he is the focus of attention.

"Jewish king" was what little Alex's Polish great-grandmother, Natsia, called him. The Polish word żydowski is a normative expression that means "Jewish." The Slavic word zhid/zhyd (Yid), was supplanted, first in the Russian language, then introduced from the Russian into the Ukrainian and Belarusian languages, by the ancient Greek borrowing from the Western Semitic languages: the word ievrei (Hebrew) is an exonym, which literally means a "person that has crossed [from one bank of a river]." In this lies the paradox of the replacement of the word zhyd by ievrei: The rejection of the humiliating word zhyd endowed this pejorative with mysterious meaning:

And she, already so sad and inconsolable,

says softly softly, God forbid anyone hears —

my Jewish king,

my puppy, my baby bird

may thy kingdom come

All kings, even "Jewish" ones, as befits every monarch and, in contrast to all manner of commoners, have a pedigree; in other words, they have the right to an immense genealogy. The author presents the reader with his own family tree, which resembles an Old Testament genealogy: a list of names of men and some women and the cities from where his ancestors came. The beginning is purely biblical:

the lineage of Oleksandr, son of David, son of Abraham

Abraham sired Isaac

Isaac sired Jacob

Jacob sired Judah and his brothers

Judah sired Perez and Zara by Tamara

Perez sired Esrom, and Esrom sired Aram

Aram sired Aminadav

Aminadav sired Nahshon

Nahshon sired Salmon

Salmon sired Boaz by Rahab

and Boaz sired Obed by Ruth

Obed sired Jesse

аnd Jesse sired David

The similarity to the Book of Genesis is strengthened by the very first line: "the lineage of Oleksandr, son of David, son of Abraham." Just in case, I remind readers of the author's patronymic: Mykhailovych. David and Abraham were the legendary king and the legendary first ancestor of the Jewish people, respectively, neither of whom are the direct ancestors of the poet, who found his genealogy in the sacred history in the Book of Genesis.

The poet's genealogy is Jewish, inasmuch as the names of real people are given according to legendary patriarchs, and the mixing of Jews with other peoples in the Ukrainian lands is raised only at the end of the poet's family tree.

Just as we do not know about the majority of people who are mentioned in the Bible, apart from the list of names, neither do we know about the poet's ancestors. We can only imagine these legendary figures: both the desert Bedouins in the territory stretching from the Euphrates to the Jordan, where the probable ancestral homeland of the ancient Jews is located, and the small-town Eastern European Jews with their typical occupations, warm family environment, and impoverished daily lives, much-read books with leather bindings and the sacred letters inside these bindings. The author knows that his Jewish great-grandmother, Rachel, came from the Podillian town of Dashiv, in today's Haisyn County, Vinnytsia oblast, where during the Holodomor of 1921–1923:

Bondarenko the neighbor

brought home a whole handful of makukha [oilseed residue]

told mother

wrap it in a rag

and give to Sheina and Zissel

to suck on

so that they'll survive until March

The birth of the poet, in whose name this book begins, is cloaked in the mystery of a romantic drama. How can one not ask the question: What does the personal mean for literature? It is not out of curiosity that Averbuch reveals to readers his family history, in which his father did not accept his pregnant mother because he did not believe that she was pregnant by him, and he rejected his son. I will hazard to guess that a person without a father and "legal" origin should himself discover his roots, pave his way into adulthood, and assert himself before the world.

I will return to the poetry collection. That rejected son found his father's family in Rostov-on-Don, where he became acquainted with his sister, blind from birth. She believed that her brother was standing in front of her, and she regained her sight. A biblical miracle: She saw her brother and, in rejecting her father's blindness, she saw the world!

The first section of the book concludes on a note of nostalgia for the hometown of Dashiv, left behind by the Averbuchs. The author's voice, recalling the small town, lost as a result of the Nazi occupation and the Holocaust, calls out to the reader:

how to return to a place that doesn't exist

to one's home — how to return

if, like heavy grief, it is gone

renamed streets

like swollen blood vessels

do not find the confluence

and you're standing up to your neck in this flood

The final poem in the first section, where the poet's voice seems to float above the old Jewish cemetery — an alien island amidst contemporary realities — continues:

How their undulating names

on the fallen gravestones turned green

like plants transported from far away

cling to the earth and water with every tiny whisker —

so that they would be remembered

but today they are known only to Podillian nanny goats

and he heard, too, muffled sounds

that reminded him of the drawn-out "zhy-y-y"

the final "d" of which

even the most outspoken and courageous

feared to utter in his presence

but out of the corner of his eye he saw how they, too,

nearly soundlessly

painted in the air with their lips

the sibilant kiss:

strangers strangers

In this requiem for Dashiv and the Jews of Podillia, sibilant sounds echo and intermingle above the Jewish cemetery: "J-Jews-are-strangers…"

2. Letter-poems

The family history and the fate of great-grandmother Rachel, who is named after one of the biblical progenitors of the Jewish people, the beloved wife of Isaac, are interwoven with the history of her Ukrainian neighbors. The author presents the history of his family and their Ukrainian neighbors from Podillia through the prism of the Ukrainians' correspondence. Thus, the pages of the Averbuch family history during the Holocaust emerge from the interweaving of Ukrainian and Jewish stories.

The language of the letters recreated by the poet is deliberately close to colloquial language, with its stuck-together words and incorrect vowels. In general, it resembles surzhyk, a mixture of the Ukrainian oral and Russian written languages. It is no surprise, therefore, that this section is entitled "So I Will Never Forget about in Regard to You." This is the subject of the first poem in the third section of the book:

I don't know

the ssian language

I don't know the ainian language

I keep silent awkwardly

This "I don't know the [Ru]ssian [Ukr]ainian language" clearly signifies, not ignorance of languages, but the basic lack of knowledge of literary languages with not so much their standards and rules as the discourses on what is "correct" and "incorrect," what has "authority," and what must recognize "authority." Not knowing a language is the same thing as being outside the bounds of authority and the division into "our people" and "strangers." Averbuch's characters are Jews; even their king is "Jewish," and that is why they have no power. They are not “ours”, so they "keep silent awkwardly."

Letter-poems are a highlight of the work of Averbuch, who created this genre. Earlier, he wrote frank poems in the name of his characters in the Russian language, basing himself on their written testimonies, as he put it in his interview with Vitaliy Lekhtsiyer (Tsirk "Olimp" TV). At first, he set out one family history, not in the style of a letter, but in a confessional style, similar to the letters of Ukrainians featured in The Jewish King. He conveyed this "storytelling" of a Jewish woman in the vernacular — incorrect from the literary standpoint — in the poem "Zhitie," which was published in 2016 on the website https://www.cirkolimp-tv.ru.

I was born into a not rich family but not a poor one

In the shtetl of the bairamchi in bessarabia was the third

in 1903 father was mobilized for the Japanese war

his childless sister helped

a pogrom happened in 1903

a priest came from a nearby village

a friend of uncle's and took us to his home

but we couldn't go because the little one had measles

so they hid us in a neighbor's stable

at dawn the stable boy took pity and brought us

through back alleys to his neighbor Krychuk

along the way we saw burning houses and two guys

sitting on the back of old man Zilberman

they are driving him it is a horrible scene

it is always before my eyes would that I wish I could forget it

that's how we made it through remained alive

Then the family history is recounted in several parts — acts of a family drama that played out during various periods, which lasts until the postwar era, around 1946.

Averbuch’s next work is “erlaubt” (Ger. "permitted," from the Jerusalem almanach Karakёi i kadikёi, no. 3, 2015). This selection of poems contains the correspondence of the members of a Jewish family scattered in Tallinn, Riga, and Palestine between 1932 and 1939. The short lines of free verse convey colloquial speech that, although literarily correct, contains German admixtures. Accompanying the poems are facsimiles, likely of genuine letters. I wonder whose letters they are?

The author talked about the two corpuses of texts, "Zhitie" and "erlaubt" in his interview with the Russian writer Linor Goralik:

"The language in these texts is something very principled, basic. I wanted to preserve it, to learn how to speak it at the point where documentality/documentariness ended, and fiction began. It is like patois or dialect: A person arrives in a new place, listens, keeps quiet, but after some time, begins to speak like the locals, with new words, phrases, mistakes. This friable, raw language is more interesting to me than the normative, smoothed-out language. There is more of the unexpected in it; it is unpredictable ("Poka tebia uzhe net" [While You're Gone], Booknik, http://booknik.ru/today/everything/poka-tebya-uzhe-net/ , 21 March 2016).

Let us return to the letter-poems in Zhydivsky korol. In order to understand what the letters from Ukrainian Ostarbeiter were, I will quote the first letter in this section in its entirety, in which this "I will never forget about in regard to you" appears:

letter dated 13.XI.43 letter from

your friend hania to her

friend marusia I am writing

the letter with my trembling hand

I send a greeting with love to my

dear friend I inform

you that up to now I am alive

and well I wish you all

the best in your young

blooming life and look marusia

I am working right now at a factory

as you know what my work and provisions are like

marusichka you too know what my life is like

so you know what it's like remember how we

were sitting at maria yakova's and hania tymkova

shouted to my mama

how they ran to the cellar that's how we are living now

marusichka I can'ttell you so you know

how good it is for me but marusichka

I don't know whether it's the same where you are as here because forus

it's very good can't be

better there is a lot of news I think

that you already know how I am marusichka

write letters don't forget me

write your news how you are living and how

daddy and mama are they are poor sick

what are they doing poor things marusichka

pass on my greetings to your mama and dad sister and sasha

and to all my acquaintances

and write letters don'tforget aboutme

and I will never forget aboutyou

greetings hania

marusia write on this postcard to me

how life is I await a reply with impatience

From the Ukrainians' correspondence emerges the fate of the Jewish community of the small town of Dashiv. One of the letters, most likely a telegram, is a request from a Jewish man or woman to his/her Ukrainian neighbor (probably either from Averbuch's great-grandmother, Rachel, or from Frida, who will be mentioned below):

I am asking you

to inform [me] if my father

mother

are alive

and living

in the t[own] of Dashiv Vinnytsia oblast

5/VII/44

This is followed by a similarly brief reply featuring a censor's intrusion; the blacked-out word is probably "Jews":

In the town of Dashiv

2/1/42 all the ■■■■■■■■ were brutally shot

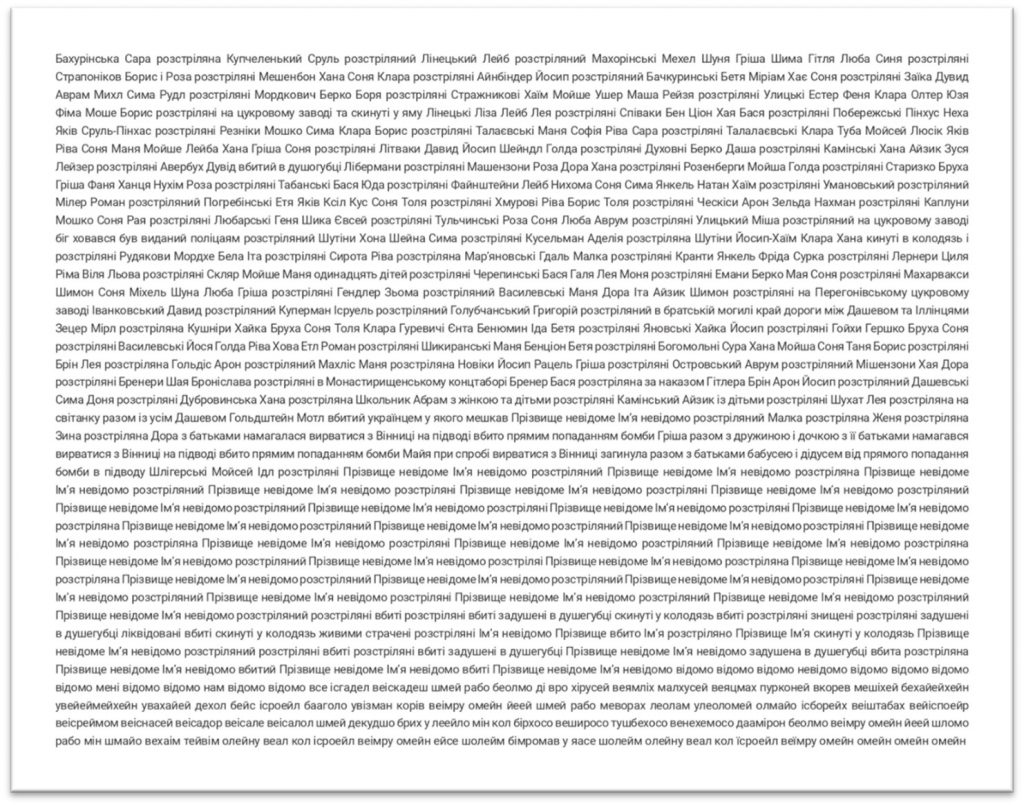

Below this letter is a full-page spread of the names of the Jews who were shot and killed in Dashiv. A substantial number of names is unknown. The list ends with a fragment from the mourner's Kaddish, transliterated into the Ukrainian and presented according to the Ashkenazi pronunciation of Hebrew. This Hebrew pronunciation is characteristic of Yiddish speakers — the Jews of Central and Eastern Europe.

The list of killed Jews is followed by letter-poems from local Ukrainians, along with a brief letter about the fate of the Jews, most likely from the Dashiv area:

a reply to your question

the Shutin family remained in the occupied village

Chana was thrown alive into a well

Klara (daughter) was thrown alive into a well

Chaim-Yosyp Shutin was killed and thrown into a well

The fate of the Jews was death, and the fate of Ukrainians — deportation to forced labor in Germany. The detailed nature of the letter-poems from the Ukrainians is striking. The poet did everything to ensure that his readers sensed the experience of Ukrainian peasants in German slavery, torn apart from their families.

Finally, I will share my conjecture on how the author came to create the genre of letter-poems. I am convinced that he was influenced by the Averbuch family correspondence. On the website COLTA.RU he published letters from his grandmother, who wrote them to her grandson in the final weeks of her life, when she was gravely ill. She placed her e-mails using the delay send optiond, and over the course of several months after her death, Alex received letters from his grandmother. I will cite the first half of the first letter [written in Russian] from his published selection — a heartfelt declaration of a grandmother's love:

"Sashunia, you will receive this letter when I shall no longer be the way you are used to seeing and knowing me. It's such a shame that I will not last until your birthday, will not call you on Skype and wish you well in person! It is strange that right now, I am wishing you well as though I'm not alive. Although I am certain that my love is no less real. I want you to know how dear you were to me even before you were born. You and I were practically inseparable all those 34 years, and with this letter — from outside of life — I want to tell you that even now we are together, only a bit differently, and you will become accustomed to this and to me this way and to my love, near and mute. There was no man in my life with whom I lived longer and more happily than with you. You were my idol, and when you were leaving for Israel (who could have thought that I, a sixty-two-year-old woman, would have so much energy to start a new life?!), I dashed after you. I arrived, and you had already rented me an apartment and furnished it, you brought new tableware, bought food. And I was happy because I realized that I had not made a mistake even in my old age, having chosen you as my life companion — you, my grandson."

Since the author of the reviewed book and this reviewer are discussing Ukrainian-Jewish relations, I cannot help quoting the fourth letter about the difficult family life and the poverty of this single mother of three children, which talks about antisemitism:

"My God, when I finally made it to that Israel (which destroyed me — how else to call the fact that they "didn't spot" my breast cancer? Accursed Israeli medicine), I finally exhaled. How much hatred they harbored for us all our lives, and what I did is, I tried to hide it in front of the girls somehow, to smooth things over. Like, what good neighbors and colleagues. But how did mama live? How was she, living as Rachel Averbuch her entire life, happy about all this? Although I think I understand. It is fortunate that there were no listening devices at the time. I have also rejected what you 'organized' for me. I don't want to hear anything. Yet not remembering anything doesn't work. How would it be to forgive everyone? This doesn't work for me, Sashunichka. I hold a grudge. Why did they hate us? Because I was a Jewess in our village? Because my mother healed everyone who came to her day and night? Because I taught more than a dozen generations of pupils [sic] in the school in Aidar? Why did they hate me? Because I threw out my carousing husband? Why did I need ……………. for an apartment for myself and three daughters? I think about all this, Sashunia, my beloved grandson, and I understand that, in dying, I still have not figured out this world."

Everyday antisemitism was a close companion of Jewish life. Today it is receding into the past, thanks to two factors: socioeconomic and sociocultural. The first resides in the fact that for Ukrainians, Jews have stopped being competitors; today's Ukrainians are not at all a "rural nation"; furthermore, very few Jews are left in Ukraine. And the second factor is the decrease of xenophobia among young people toward their peers with whom they share their upbringing and values of European Ukraine.

3. Requiem for Novoaidar

Whereas the first section of the book concludes with a requiem for Podillian Dashiv, the third section, "The First Impression of Nonexistence," is a requiem for the poet's hometown of Novoaidar in Slobidska Ukraine, in the Luhansk region.

The first image of Novoaidar is a city bereft of memory. In order to convey the sense of past devastation, the author compares his town to the atomic city of Prypyat, all of whose inhabitants were evacuated in May 1986:

it's as though it's not about you

when you finally fall asleep

in a fog of radiation

after two or three hours

not very familiar silhouettes appear

they move slowly

from our house to the neighboring one

and I seem to hear their choppy speech

this lowing, on which every reference

to oneself flies away from the walls of the prefabricated buildings

of an almost nonexistent city

Then:

when are you finally lucky

to the radiological mixture of small

solid particles

comes the memory

of a destroyed city

the May 1st garden a woman in a polka dot dress

lost you during a time

of heavy exhaustion

The other image of Novoaidar is war and refugee status. Averbuch left Ukraine in 2001, when he was sixteen. But his poems were influenced by the war in the Donbas and the refugees who abandoned their homes, retaining, like Lot's wife in the Bible, the memory of their hometowns in their hearts:

we retreat from memory

your clumsiness

leads us over a river

by muddy roads

look, they have abandoned their equipment

and you greedily inhale

the January air

stinking of gasoline

In the final poem of the book we read:

people who leave a place

of residence

during war

acquire the look

of wounded people

sometimes killed

but gradually

the horror in their eyes loses

its previous coloration

the mess of life

leads

suffering

to waste

the only thing that we long for now

is recognition of our pain

4. The breathing of free verse

The third section of the book is short; thus, now is the time to address the poet's style of writing. The entire book is written in vers libre. The lines of free verse are short, as a rule, containing two or four tones, that is, two or four distinct emphases within a single line. The exceptions are the long lines of the author's family tree and the circumstances surrounding his birth. They are reminiscent of tongue twisters, owing to the effort to pack a lot of things into a single line — in a single, long breath.

When they are voiced, the short lines recall calm breathing or a beating heart as well as waves of memories. In my opinion, the latter effect is the main one characterizing the lines in this book. They speak to the reader; the poet's characters address their descendants. The reader, who seems to have fallen into history's embrace, senses its rapid and heavy breathing.

The poems in the first and third sections become chapters and subchapters of a poema, a long poem; they appear to be incomplete, and they flow into each other, like little pictures and recollections, thus creating an atmosphere of familial memory about one's home and family. Unlike Lot's wife, Ukrainians have experienced their importance in a painful way. They have often looked back to gaze upon their cities, then frequently returned to their homes in 2014 and again in 2022.

Published on 20 August 2022

Mykhailo Gaukhman

Translated from the Ukrainian and Russian by Marta D. Olynyk

Originally appeared in Ukrainian @Ukraina Moderna

This English-language article is an abbreviated version of the Ukrainian, which was published as part of a project supported by the Canadian non-profit charitable organization Ukrainian Jewish Encounter.

Alex Averbuch's collection, provisionally titled The Jewish King (trans. by Oksana Maksymchuk and Max Rosochinsky) is forthcoming with Lost Horse Press in 2024.