In search of Hrytsko Kernerenko, person without a profession: A genealogical mystery

"Which is the straight path that a man should choose for himself? One which is an honor to the person adopting it and [on account of which] honor [accrues] to him from others."

Talmud, Pirkei Avot 2:1

"After death, glorious is the man about

whom sincere words are spoken."Hrytsko Kernerenko, The Cemetery

Mykhaylo Frolov and Serhii Zvilinsky

The 2016 issue of the Museum Bulletin of the Zaporizhia Regional History Museum featured an article by Serhii Zvilinsky entitled "The Kerner Merchant Family: To the Question of Jewish Capital in the Socioeconomic Relations of Southern Ukraine, Late Nineteenth–Early Twentieth Centuries." [1] The article discusses the great contribution of the Kerner family to the development of industry in southern Ukraine and the Russian Empire, in general. Since then, research into the history of this family has been expanded thanks to Mykhaylo Frolov, whose family tree is connected to one of the branches of the Kerner family. Important archival materials have been identified, allowing us to significantly expand information about the family.

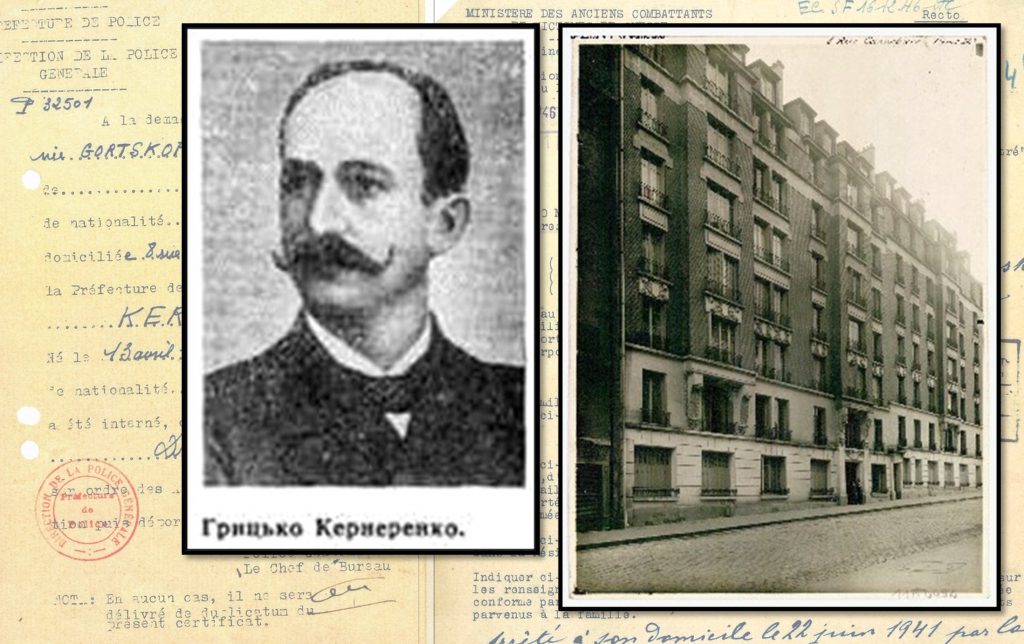

The article mentions one of the most illustrious representatives of this enormous Jewish family from Huliaipole: Hryhorii (Hirsch) Borysovych Kerner, a poet, writer, and translator who is better known by his pseudonym Hrytsko Kernerenko. He has been the subject of serious philological research. The most exhaustive study, which includes a detailed analysis of the "improbable identity" of Kernerenko, the poet, was written by Professor Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern, an American philologist, essayist, and researcher specializing in Jewish history, who analyzed both the persona of this famous native of Huliaipole and his considerable literary legacy. [2, 3]

What is this "improbable identity"? Explaining the unique nature of this personality, Petrovsky-Shtern states that for a former shtetl Jews from the Pale of Settlement to identify with another persecuted minority such as the Ukrainians or Lithuanians, rather then to seek the safe haven under the aegis of the Russian-language imperial or Soviet culture, was unusual, if not abnormal. Having become accustomed to discussing the East European Jewish interaction as Russian-Jewish or Polish-Jewish, we are not even able to answer superficially the question of whether there is or ever has been a Ukrainian-Jewish literature, or to come up with the list of texts that might fall under the rubric "Ukrainian – Jewish" [2].

According to Petrovsky-Shtern, Hrytsko Kernerenko fills this gap and may be the first Ukrainian poet of Jewish descent to contribute to what could be cautiously dubbed the Ukrainian-Jewish literary tradition [2]. He proceeds to state that we can only speculate about why and how Grigorii Kerner started to write Ukrainian verse, we do that Kernerenko’s poetry, appearing between 1890 and 1910 … did not go unnoticed by Ukrainian literary figures [3]. Having acquired a brilliant education both in Russia and abroad, he wrote poems, short stories, and plays in the Ukrainian language at a time when this was not welcomed, to put it mildly. He translated the works of Sholem Aleichem, Shimen Frug, Semyon Nadson, Heinrich Heine, and Alexander Pushkin from the Yiddish, German, and Russian into Ukrainian. In Huliaipole, he published five books, including four collections of poetry. [3] His works appeared in various anthologies, including in the journal Literaturno-naukovyi visnyk, published in Lviv by Ivan Franko and Mykhailo Hrushevsky, and he corresponded with Franko in this connection. The poet was not compelled to publish his works for financial reasons because there was enough money in the Kerner merchant family of the First Guild. In one of his letters to Franko, Kerner informed him about Sholem Aleichem, and in 1906 Franko published Kernerenko’s translation of the short story "Uncle Pini with Aunt Reyzi." This unique stance was none too well received either in the Ukrainian or the Jewish literary milieu. In 1896 Pavlo Hrabovsky wrote a critical article entitled "Something about Poetic Creativity," addressing Kernerenko’s collection of poems. The article begins with the following words: "I have not seen either that collection or the author’s previous works, so I do not know how much they actually merit such harsh criticism. In any case, this question does not trouble me." [4]. No comment, as they say. Contemporaries’ perceptions of Kernerenko were formed in keeping with these kinds of stereotypes.

In his native Huliaipole, Kerner was active in the amateur theater based at the agricultural implements plant of the trading house Boris Kerner & Sons, where Nestor Makhno had acted in his youth. Kerner’s wife, Rebecca, was involved in charitable works and was the founder and guardian of the Jewish women’s school in Huliaipole. During the First World War, she helped the local infirmary and Jewish families whose husbands and fathers had been killed in the war. It is known that Hryhorii and Rebecca had three sons [3], whose names we discovered during our research into the Kerner family tree: the twins Yakov and Victor, born in 1897, and their younger brother, Emile, born in 1899.

However, the biography of this outstanding literary figure contains countless lacunae, giving rise to numerous speculations and fantasies on the part of researchers and triggering more questions than answers. The biggest gap in the poet’s biography concerns his life after the events of the Ukrainian Revolution of 1917–1921. The activities of the Kerner family took place mainly in perhaps the most revolutionary town in southern Ukraine: Huliaipole. After Makhno’s failed attempt to build a free republic and the Bolsheviks’ rise to power, the Kerner family dispersed within the turbulent socioeconomic processes of the early 1920s, and all traces of it vanished. This spurred local historians into spinning fantasies about Kernerenko’s death in the early 1920s, which spread through the Internet and diverse local history publications featuring fragmentary biographical data about the poet. This uncertainty and the absence of Kerner’s grave at the Jewish cemetery in Huliaipole, where other members of his family were buried, were intriguing. The question lingered in mid-air. But first things first.

Everything started when a few of Anatolii Tarasenko’s[i] translations of Kernerenko’s poetry into Russian were discovered on the Internet; the date of death, 1921, was mentioned.

From our private correspondence with A. Tarasenkoi dated 27 May 2015:

Hello! My name is Mikhail Frolov. I live in Ukraine, in the city of Zaporizhia. I am writing to you about the following; if necessary, I apologize in advance for troubling you. On the Internet (http://samlib.ru/t/tarasenko_anatolij_wladimirowich/tom4.shtml) I found the publication of the fourth volume of your collected works and in it, "Hey, you, stepfather, the wide steppe … Poetry of the Nineteenth–Early Twentieth Centuries." My attention was drawn to a section about Grigorii Kerner. The fact is that I would like to collect some information about my family history, and the Kerners are part of this history. Unfortunately, this desire has emerged at a time when those who could tell me something are no longer alive. In addition, I have become interested specifically in Grigorii. Since you are the only one to have indicated the date of Grigorii Kerner’s death (all other authors state ‘date of death unknown’), it occurred to me that you might have more information about this and about the Kerners, in general. I would be grateful if you would deem it possible to share your information.

Dear Mikhail! Unfortunately, for me, too, the date of Kernerenko’s death remained unknown, but then I came across information that one of my contemporaries pointed out… I have a suitcase with an inconvenient, pre-computer archive, but I have not gone through it because there is nothing else there, not even the name of that contemporary.

18 March 2016:

About Grigorii Kerner’s (Kernerenko’s) date of death… An Internet search reveals that in my book Dialogue of Poetry, I am the only one to mention the concrete date of 1921. In other words, I am becoming a reference source. Naturally, you are asking me to dig around in my pre-Internet archives in order to obtain information about the origin and reliability of the information… [Sometime in the mid-1990s] I came across the reminiscences of one of my contemporaries about the last time that he saw Grigorii Kernerenko in Huliaipole in the fatal famine year of 1921. The poet looked sickly; at the time, everyone’s means of subsistence were negligible and therefore, according to the news of his fellow countrymen, Grigorii allegedly died there that same year...

… It seemed to me that the information was from the memoirs of Anatolii Gak [Ukr. Hak] in the form of news from the distant homeland. However, as it turned out, there is no such thing. Most likely, it was a bit of information from one of those Ukrainian media sites (possibly Zaporizhia) that work with the current resource without archiving. However, I think that sooner or later, it will surface.

No answer was found in this connection. However, one needs to bide one’s time while conducting such searches. Life itself brings interesting surprises and offers unexpected hints, and you simply begin to look at well-known things with fresh eyes. The information surfaced.

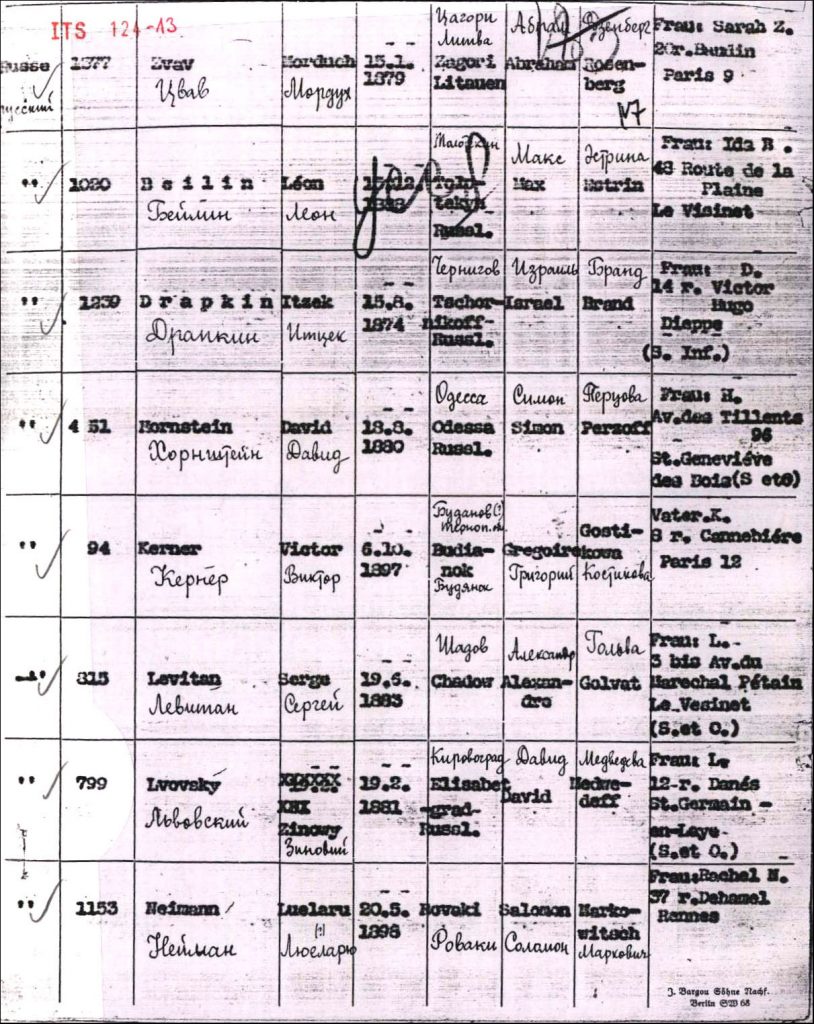

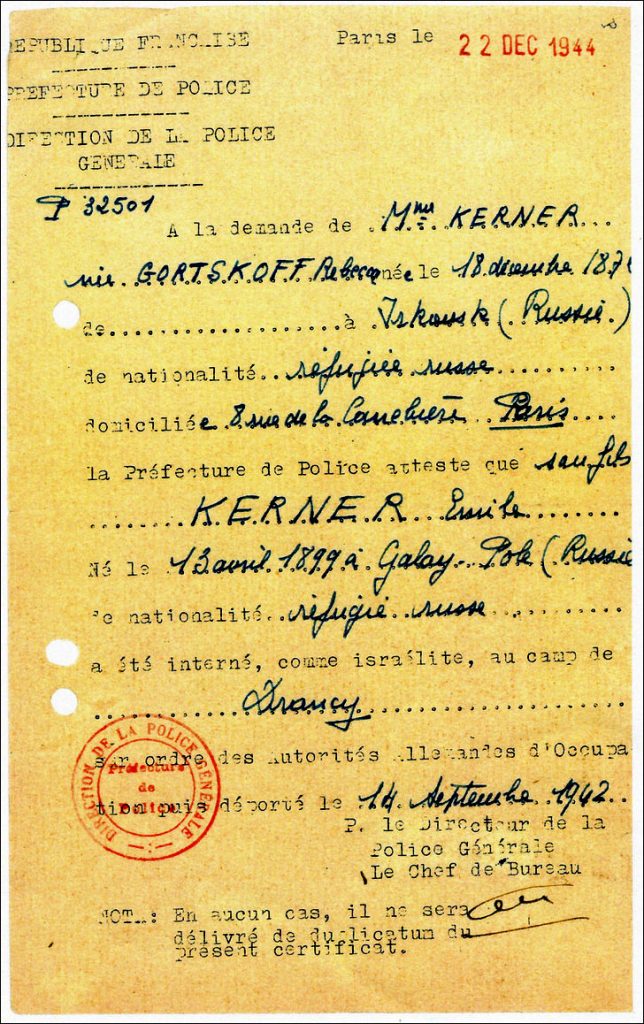

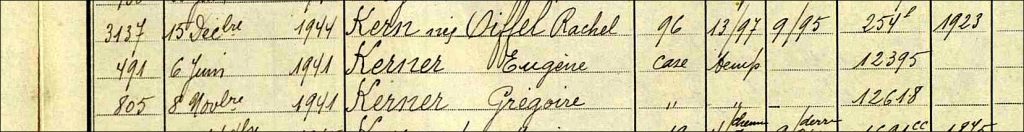

The key to the solution turned out to be a captured German document that was discovered in open-access online sources: an accounting log kept by the German occupation administration in the city of Paris with the unassuming title Zu und abgänge (Arrival and Departure), as though it concerned business trips. In fact, it concerned arrests and deportations. [6] This document appears on the website of the Arolsen Archives, the International Center on Nazi Persecution. Listed under no. 94 is "Kerner Victor," date of birth: 6 October 1897; place of birth: Budianok; father: Grégoire, mother’s maiden name: Gostikova, date and place of capture: 25 June 1941; health status: "healthy"; father’s home address in the 12th Arrondissement of Paris; and a notation that is truly horrifying: "5 September 1942 nach Drancy uberstellt," meaning, that he was transported to Drancy. The Drancy internment camp was not a death camp; it was just hell’s lobby, a transit point for isolating Jews and other people slated for deportation from France.

The deportations from there took place mostly to the Auschwitz and Sobibor death camps. Out of 70,000 Jews who passed through Drancy, 61,000 were sent there. [7] According to available information, biographical data indicate that Victor was one of Grégoire Kerner’s sons. From this point, two search directions appear. The first is everything connected with Grégoire, who is mentioned in the document as Victor’s father. Therefore, if this Grégoire is indeed Grégoire Kerner, then "Budianok" is probably Berdiansk. This is definitely a success because we obtained Grégoire’s home address as well as confirmation of his death in 1921, even though he was still alive in 1941. The second is determining the fate of the other family members, particularly the sons, although theoretically, everything was clear here.

Anyone who uses the online Paris Archives knows that the system is not overly complicated. But a minimal knowledge of French and a maximum number of source facts are required in order to reduce the number of documents to be examined. Documents have been digitized but not indexed. A selection can be made according to type of document, year/s, neighborhoods within districts, and some—alphabetically. There are alphabetized registration books that are grouped in chronological order by year and district, and separately by decades.

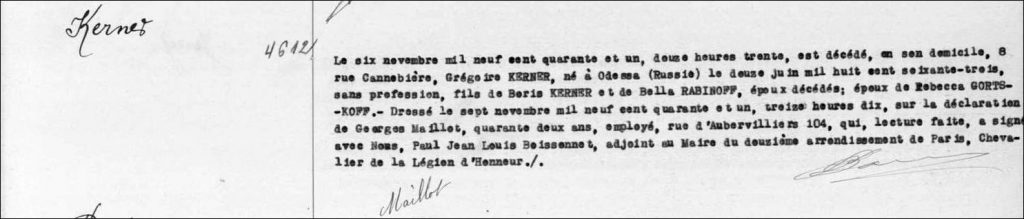

During the search, you also need to consider the numerous restrictions that exist in France concerning documents containing personal data. All researchers who work in the French archives are also familiar with the "filiae" [daughters] resource, where many documents have been indexed and offer the possibility of searching for a specific person. However, the documents themselves can be obtained only by subscription. However, one of the online filters can save you time and money if you limit the search of years by clicking on "from–to." At this point, you can proceed in a variety of ways, starting with the method of half-division (a well-known method for the numerical solution of mathematical equations) in order to determine the exact year of the document—if you are lucky. In our case, we got lucky because the document pertaining to Grégoire Kerner, specifically, the record of his death, was dated 1941. A search of the documents on the website of the Paris Archives for the 12th Arrondissement in 1941 yielded the following document, the registration of death no. 4612 [9]:

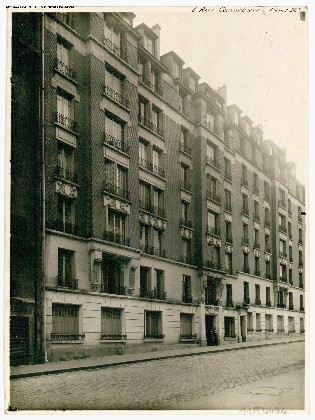

Grégoire Kerner, who was born in Odesa (Russia) on 12 June 1863, without a profession, son of Boris Kerner and Bella Rabinoff, both deceased; husband of Rebecca Gordskoff, died on 6 November at 12:30 at his home on rue Cannebière. Recorded on 7 November 1941 at 3:10 according to the declaration of George Mafllet, 42 years old, worker, 104 rue d’Aubervilliers, who signed it, as did Paul Jean Louis Baissennent, an employee of the City Hall of the 12th Arrondissement of Paris, Chevalier of the Legion of Honor.

Thus, given the complete correspondence of biographical facts, we are able to state that Hryhorii Kerner did not die in 1921 but became Grégoire. The document does not indicate that he was a widower, which means that his wife, Rebecca, was still alive at the time. From this moment, there is no longer a dash in the place indicating Kerner’s date of death, which is 6 November 1941.

The next step was to study censuses. The family was found relatively quickly according to the address listed in the census of Paris residents for 1931 and 1936: Grégoire Kerner: head of the family; Rebecca Kerner: wife; sons: Jacques (Yakov), "employé" (which may designate the profession of a hired functionary or a worker); Victor: taxi driver; Emile: taxi driver. For some reason, we picture this family at a round table. There may have been a certain level of affluence because the apartment was not located on the outskirts of Paris. But life forced the members of this formerly very wealthy family not to disdain any work. According to the 1926 census, the family did not reside at this address, but the census of 1946 is, regrettably, available only in the reading room of the Archives. [10,11]

Another source of information is the Archives of the Main Police Directorate of the Police Prefecture. One query and four months of waiting, and the result was Grégoire Kerner’s registration card no. 1530891 dated 1 July 1926. The indicated residential address is 8 rue des Carrières in the town of Clamart, near Paris. This explains their absence in the 1926 census and provides grounds for assuming that they moved to France sometime in the first half of the 1920s.

Registering and opening an account on the website of the French National Archives reveal another layer of documents: naturalization decrees. Many documents have been digitized and indexed. Unfortunately, nothing was found there, but the lack of a result is also a result. The absence of Grégoire Kerner’s name in the decrees covering 1925 and subsequent years may indicate that naturalization took place before 1925 and that these documents have not been indexed. In this case, the service invites users to send a query to Archives, which we did.

From the reply sent from the French National Archives on 25 November 2020:

Sir,

The study of auxiliary search tools related to naturalization applications, in particular, the alphabetical files of naturalization applications between 1848 and 1930, created by the Ministry of Justice and stored in the BB / 27 sub-series, did not allow us to find a trace of the naturalization file for Grégoire Kerner.

Respectfully,

Eric Diouris

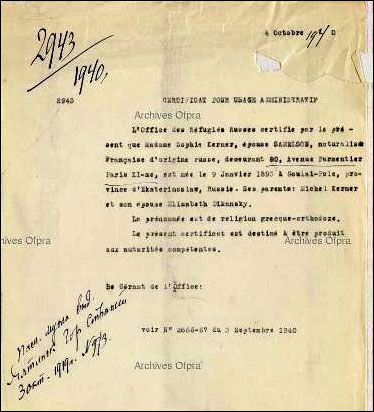

There is no one from the family in existing electoral lists either, although the registration card of Grégoire’s nephew, Eleazar Kerner, the son of his brother, Michel, dated 1933, exists, as does his naturalization decree and that of his son, Eugène, dated 27 March 1929. [12] But was there any naturalization at all, or had they been living in France on some other basis? If the Kerners arrived in France in the early 1920s, then they could have done so as refugees from Russia, and this brings us to yet another archive: The Archives of the French Office for the Protection of Refugees and Stateless Persons (OFPRA). The documents found there, as well as subsequent discoveries, corroborated the Kerner family members’ status as "Russian refugees." OFPRA’s Russia Collection contains three documents related to Grégoire’s sons, Victor and Emile. One of them is "Certificate no. 3385 for Administrative Use," which was issued to Emile Kerner in order to obtain a Nansen Certificate of Identity, dated 20 October 1938 [13], which also indicates that Emile Kerner, a Russian refugee, arrived in France in 1926 from Czechoslovakia with a Czechoslovak passport and a French visa that was issued in Prague on 24 December 1925. Thus, it is most likely that in late 1938 the Kerners, who had Russian refugee status, were still stateless persons. Two other documents—Certificates nos. 2938-39 and 2940-41, dated 4 October 1940—were issued to Victor and Emil Kerner, respectively, for presentation at the General Consulate of the United States of America. [14, 15] In occupied France, they probably made an attempt to save themselves in the U.S., but this did not happen.

Another OFPRA document allowed us to go even farther in our research. Some time earlier, on 3 September 1940, their cousin, Grégoire’s niece, Sophie Samelson (née Kerner), obtained a similar document, Certificate no. 2666-67. [16] Our attention was drawn to a Russian-language inscription on the certificate, obviously made by a functionary of OFPRA’s Russia Office: "Husband’s passp[ort] iss[ued] by the Yalta Cit[y] Gua[rd] on 3 Oct. 1919, no. 973." In other words, the path to Europe for other Kerner family members as well as thousands of refugees from postrevolutionary Russia could have traversed Crimea to Constantinople and beyond. We were not wrong.

The numerous genealogical and historical groups on social media are an invaluable source, if not of information, then at least valuable advice. In our experience, people with shared interests gladly help each other with searches in a completely selfless way. Thanks to the advice offered by the popular English-language Jewish genealogy group Tracing The Tribe, or TTT, we found a group called Russian Wartime Emigration, 1920–1945: People, Facts, Events. Replying to our post requesting help, one of the group’s members, citing documents of the processed part of the collection, "Main Information Office, Constantinople," from the State Archive of the Russian Federation (GARF), provided the following information: "List of Emigrants Living in Tuzla Camp, 1920–1921" [17], and the document: "List of People in Barrack no. 2, 12 December 1920," which revealed the following information:

Kerner Grigorii Borisovich, manufacturer

Kerner Reveka Mikhailovna, his wife

The Main Information Bureau in Constantinople was set up in May 1920 in order to collect and issue information on the whereabouts of Russian emigrants [18], and the Tuzla camp for refugees from Russia was located near Constantinople. The kind of steamer on which the family sailed to Turkey and how the Kerner couple’s journey to France proceeded could have been identified with the aid of the documents generated by this office, but most of them were destroyed back in 1922 by the Bureau itself [18], and most of the remaining ones have not been processed. The path of Grégoire and Rebecca’s sons was more readily comprehensible because the 1922 document from that same collection [19] entitled "List of Students Who Left through the Union of Russian Students in Constantinople to Prague Educational Institutions to Continue Their Higher Education" contains information about all three sons. The Union of Russian Students was founded in 1921, and in 1922 Czechoslovakia opened its doors to young people from families of refugees from Russia so that they could continue their education. [20] Now it is clear why Emile Kerner came to France from Czechoslovakia.

Given the large-scale evacuation that was organized from Crimea in late 1920, after Wrangel’s troops [White Army general Piotr Wrangel—Ed.] were defeated, it may be supposed that the Kerners were part of this first emigration wave and ended up in Turkey, where they stayed until at least 1922. Then Hryhorii and Rebecca could have come to France from Czechoslovakia, together with their sons, which tallies with the first mention of them in the above-cited information from the Police Prefecture.

Interestingly enough, the last time that a few of Hryhorii Kerner’s poems were published, after a lengthy interval, was in 1922 in Berlin, in the anthology Strings: An Anthology of Ukrainian Poetry from the Earliest to Most Recent Times. [21]. Scant attention was paid to it, perhaps in the belief that the poems included in this anthology were simply a tribute to the talent of a poet from "ancient times." However, given the information that is available today, the fact of its publication appears in a somewhat different light. These are not "most ancient times" but "today." Could it have been an attempt to resume literary activity? The poem "Na chuzhyni" (In a Foreign Land) sounds particularly eloquent:

My land! Why

do I long bitterly

when I leave you?

I myself do not know why I shed tears—

Something presses, something torments me!

There are people here, too,

And the sun shines everywhere—

It warms everyone, charms everyone…

But my heart is heavy,

Though I am among people—

I do not care.

It’s the same for a little bird,

Bored in its cage,

Even though that cage is golden,

It keeps looking out,

Flying to the door,

Asking the sun about freedom.

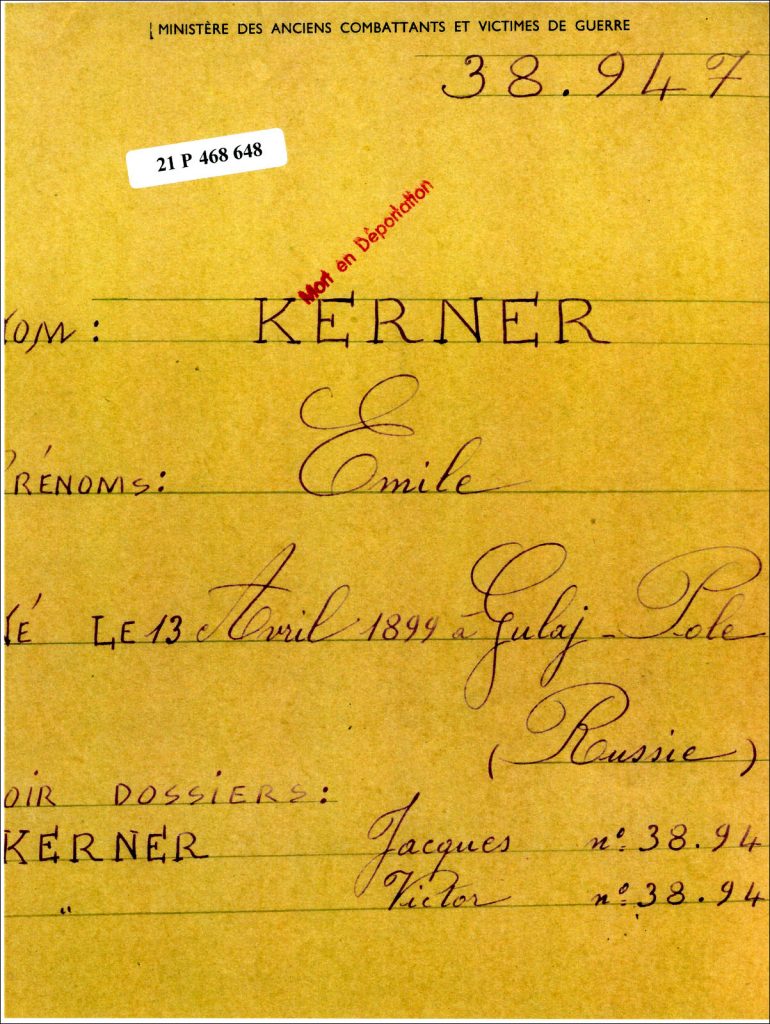

The subsequent fate of Kerner’s sons is almost clear, because only 2,000 of those who were in the Drancy camp when it was liberated in 1944 had survived. [7] The names of Jacques (Yakov), Victor, and Emile can be found in the lists of Jews who were deported from France; they are available in open sources [8], Yad Vashem’s name database, and on the website and the Wall of Names of the Shoah Memorial in Paris. [8] The information that was available to us at the time allowed us to introduce certain correctives to the information held in the databases of Yad Vashem and the Shoah Memorial in Paris.

From a letter sent by the Shoah Memorial (Paris) on 19 June 2020:

Dear Mr. Frolov,

I confirm receipt of your e-mail and the information that will allow us to correct the names of your relatives in our database of Shoah victims in Paris and our Wall of Names.

From next Monday, you will be able to see the update (particularly the correct spelling of the places of birth and biographical information, also corrected, thanks to you) on our online documentary portal.

As regards corrections to the monument, we will have to wait and see how many modifications will be approved by 2025 in order to indicate the start date of the subsequent work.

If you have any additional questions, I remain at your disposal.

Thank you very much for your interest and assistance.

Respectfully yours,

Valérie Kleinknecht

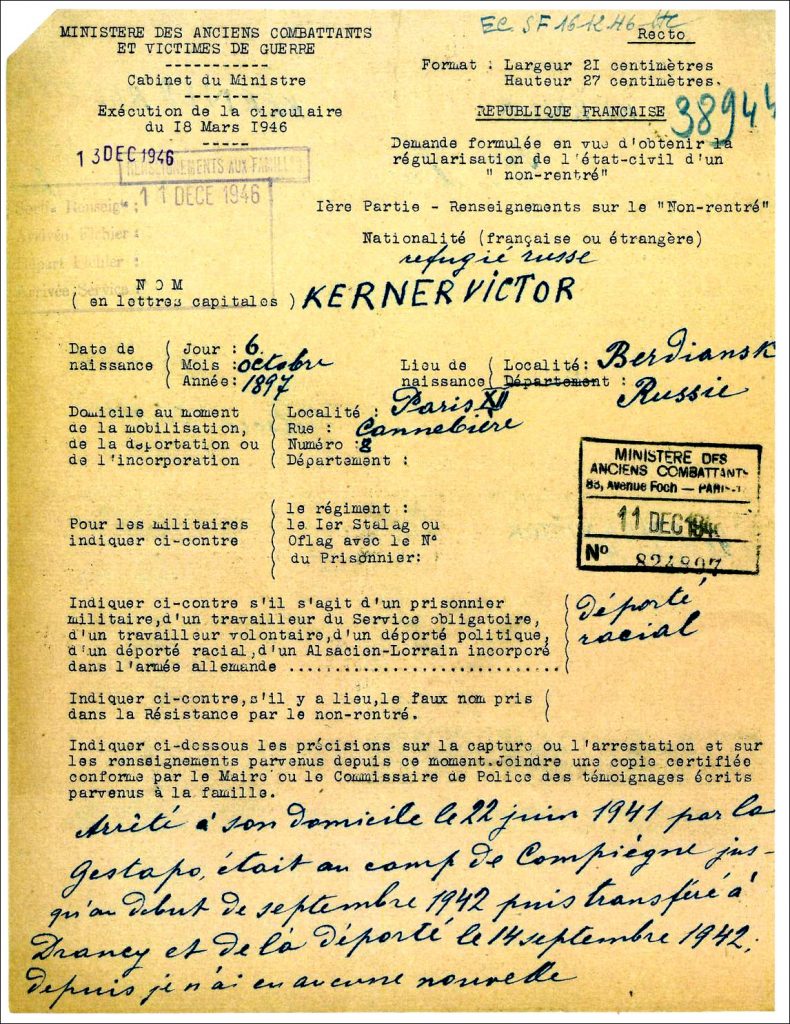

A question arises about the original source of information that exists on various portals. Clearly, there are several sources. For the time being, we contacted one that turned out to be the SHD, the Defense Historical Service, which acts as the central military archive of France’s Ministry of Defense. The service has many departments throughout France; one of them is in Caen, where files on Yakiv (Jacques), Victor, and Emile Kerner are still held. [22, 23, 24] Our correspondence, wait times, bill payment, and further wait times resulted in the receipt of copies of files that were sent by post. The files are based on the declarations of missing persons that their mother, Rebecca Kerner, filed with the police to search for her sons. The first is dated 1944; there were also declarations filed in 1946. It is noted briefly: eyewitnesses of the Holocaust, or, as indicated in the files, "racial deportations."

The declaration includes Rebecca Kerner’s explanation about the disappearance and search for her son, Victor Kerner, dated 13 December 1946:

Arrested by the Gestapo in his residence on 22 June 1941, sent to the Compiegne concentration camp, from where in early September 1942 he was transported to Drancy and from there deported on 14 September 1942. Since then, I have had no news about him.

Next, the police records about the disappearance and information noting deportation to Auschwitz are the basis for the entries recorded in the Civil Status Acts. If you also consult the list of Jews who were deported from France, it becomes clear that the transport took place by convoy no. 32, train no. 901/27 from Drancy. [8] The SHD indicates 19 September 1942 as the date of death for all three. But the website JewishGen, which has a link to a file of people who were used in forced labor at the Auschwitz concentration camp, lists the name of Jacques Kerner, a mechanic by profession, son of Grégoire and Rebecca Kerner, who was transported to the camp on 1 April 1944. [25] Contradictions are always intriguing for researchers, but at the present time nothing more can be added here. In any event, the finale, stamped in red on the title pages of the Caen files is "Died during deportation."

Be that as it may, how did the Kerner couple’s earthly journey end? In order to answer this question, we began by looking through the registration books about the transportation of bodies to Paris cemeteries, which are kept by funeral directors. Imagine: even these kinds of documents are freely accessible. During the occupation, the books covering the 12th Arrondissement turned out to be missing. So, we started looking at all of them, starting in 1947, because Rebecca Kerner was still alive in 1946 (information about Rebecca in the "filiae" was missing).

According to an entry dated 1 September 1954, the remains of Rebecca Kerner were delivered to the cemetery of Saint Ouen, on the outskirts of Paris. [26] After that, it was easy to locate the record of death (no. 2262), which happened on 30 August 1954, and the record in the cemetery’s registration book indicating the place of interment: Section 34, Line 3, Place 24, as well as the number and year of the concession: 623TR 1954. [27, 28] A cemetery concession in Paris is the right to lease a portion of land for a minimum period of time, and longer, provided payment is made. We sent a query to the administration of the St. Ouen cemetery, and received a reply within an hour.

(St. Ouen), 10 November 2020:

Hello, Mr. Frolov,

Grave 623 TR, year 1954, which is in the indicated place, does not exist today.

We remain at your disposal for any further information.

Sincerely,

Jennifer Sellier

Everything is clear. Our last question concerned Grégoire’s grave. A search of cemetery registration books for the 12th Arrondissement did not produce any results. Thus, the only thing left for us to do was to look through each and every one of the registration books kept by all the Paris cemeteries, in alphabetical order, which included records for November 1941, and hope for success. We found the record. Because we had examined everything indiscriminately, another question cropped up after we located the record of his burial: What kind of cemetery is it? Grégoire Kerner was undoubtedly a creative individual and an outstanding personality. For that reason, the choice of this particular place does not appear to be accidental, even though the burial method was not at all Jewish.

According to entry no. 805 dated 8 November 1941, Grégoire Kerner’s last address turned out to be box no. 12618 located in the columbarium of Paris’s famous Père Lachaise Cemetery. [29] The notation "Temp" indicates that the concession was temporary. Was this truly his Last Will? Had he wanted to be close to Honoré de Balzac, Molière, or Oscar Wilde, or perhaps next to his countryman Nestor Makhno in that same columbarium? The question is rhetorical.

Below is a fragment of the reply from the administration of Père Lachaise Cemetery, 13 November 2020:

Sir,

You were kind enough to draw my attention to your desire to determine whether Box No. 12618, in which Grégoire Kerner’s urn was placed in 1941, has become invalid.

This box, which was acquired temporarily, was transferred by the administration because it was not renewed after 1952.

Permit me to say that we do not have additional information concerning the deceased.

Respectfully,

Laurence Bonin

In layman’s terms, this means that the concession was acquired for a period of ten years, and since it had not been extended (probably because of non-payment) after 1952, then it «n'existe pas» ("does not exist"), as a well-known French singer once sang.

This has put an end to our search, but we want this to be a start—the beginning of the restoration of the memory of this outstanding and ambiguous personality, this person "sans profession"[ii], who loved Ukraine and who, for most of his life, aspired in his works to establish a "Ukrainian-Jewish encounter." [3]

List of Sources and Literature

- Zvilins′kyi, S. "Kupets′ka rodyna Kerneriv: Do pytannia ievreis′koho kapitalu v sotsial′no-ekonomichnykh vidnosynakh Pivdnia Ukraїny kin[ets′] ХІХ–poch[atok] ХХ st." Muzeinyi visnyk, no. 16 (2016): 148–60.

- Petrovsky-Shtern, Yohanan. "The Construction of an Improbable Identity: The Case of Hrits′ko Kernerenko." Ab Imperio, no. 1 (2005): 192–240.

- Petrovsky-Shtern Y. The Anti-Imperial Choice: The Making of the Ukrainian Jew. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2009.

- P. Hrabovs′kyi. "Deshcho pro tvorchist′ poetychnu," Hrabovs′kyi, Ukrlib, Biblioteka Ukraїns′koї literatury, www.ukrlib.com.ua/books/printit.php?tid=693. Last accessed: 10 March 2021.

- Anatolii Volodymyrovych Tarasenko, Ukrainian Wikipedia, https://uk.wikipedia.org/wiki/Тарасенко_Анатолій_Володимирович. Last accessed: 10 March 2021.

- Russian State Military Archive (RGVA), f. 1367, op. 2, d. 29.

- Drancy (concentration camp), Russian Wikipedia, Last accessed: 5 January 2021. Accessed: 10 March 2021.

- Serge Klarsfeld. "Le Mémorial de la Déportation des Juifs de France,

https://stevemorse.org/france/index.html. Accessed: 10 March 2021. - Actes d'état civil. Décès. Arrondissement 12. Côté 12D 405. Commencé à 28/10/1941 (acte no. 4486); Terminé à 19/11/1941 (acte no. 4786), http://archives.paris.fr/s/4/etat-civil-actes. Accessed: 10 March 2021.

- Recensement de population. 1931. Population de résidence habituelle. Arrondissement 12. Quartier Picpus. Côté D2M8 401. Impasse des Arts – rue Jaucourt (de 7 à 9), http://archives.paris.fr/s/11/denombrements-de-population . Accessed: 10 March 2021.

- Recensement de population. 1936. Population de résidence habituelle. Arrondissement 12. Quartier Picpus. Côté D2M8 598. Cours d’Alsace – rue Daumensil (de 183 à 199bis), http://archives.paris.fr/s/11/denombrements-de-population . Accessed: 10 March 2021.

- Fichiers des électeurs de Paris et du département de la Seine (1860-1939). 1921–1939. Côté D4M2 472. Commencé à Kern, Louis; Terminé Kernoa, René Louis Célestina, http://archives.paris.fr/s/28/fichiers-des-electeurs. Accessed: 10 March 2021.

- Kerner, Emile. OR105, Archives en ligne de l’OFPRA, https://archives.ofpra.gouv.fr/ark:/23600/a011559552987QZHEYz. Accessed: 10 March 2021.

- Kerner, Victor. OR133, Archives en ligne de l’OFPRA, https://archives.ofpra.gouv.fr/ark:/23600/a011517219374440wvc. Accessed: 10 March 2021.

- Kerner, Emile. OR133, Archives en ligne de l’OFPRA, https://archives.ofpra.gouv.fr/ark:/23600/a011517219374FOXiCb. Accessed: 10 March 2021.

- Samelson, Sophie. OR132, Archives en ligne de l’OFPRA, https://archives.ofpra.gouv.fr/ark:/23600/a011517219309abIbCu. Accessed: 10 March 2021.

- State Archive of the Russian Federation (GARF), f. R-5982, op. 1, d. 115.

- Glavnoe Spravochnoe Biuro (Konstantinopol′), Russian Wikipedia, https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Главное_справочное_бюро_(Константинополь). Last accessed: 9 June 2020. Accessed: 10 March 2021.

- GARF, f. R-5982, op. 1, d. 194.

- Repina, O. "Novyi put′ russkogo studenchestva," Russkaia traditsiia, http://www.ruslo.cz/index.php/arkhiv-zhurnala/2020/01-2020/item/1417-novyj-put-russkogo-studenchestva. Published: 26 February 2021. Accessed: 10 March 2021.

- Struny: Antolohiia Ukraїns′koї poeziї vid naidavnishykh do nynishnikh chasiv: u 2 t., vol. 2, compiled by B. Lepkyi. Berlin: Ukraїns′ke slovo; Ukraїns′ka narodna biblioteka, 1922.

- Kerner, Jacques. Ministère des anciens combattants et victimes de guerre: Dossier no. 38.946. 21 P 468 656. Caen: SHD, 1946.

- Kerner, Victor. Ministère des anciens combattants et victimes de guerre: Dossier No 38.944. 21 P 468 664. - Caen: SHD, 1946.

- Kerner, Emile. Ministère des anciens combattants et victimes de guerre: Dossier no. 38.947. 21 P 468 648. Caen: SHD, 1946.

- Lande, Peter W. "Auschwitz Forced Laborers," https://www.jewishgen.org/databases/holocaust/0056_AuschwitzForcedLaborers.html . Accessed: 10 March 2021.

- Répertoires alphabétiques de transports de corps. 1954, Côté 2484W 69. Commencé à Lettre K (25 June 1954); Terminé à Lettre L (16 March 1954), http://archives.paris.fr/s/27/transports-de-corps. Accessed: 10 March 2021

- Actes d’état civil. Décès. Arrondissement 12. Côté 12D 452. Commencé à 23/07/1954 (acte no. 1991); Terminé à 01/09/1954 (acte no. 2295), Archives de Paris, http://archives.paris.fr/s/4/etat-civil-actes. Accessed: 10 March 2021.

- Les cimetières de Ville de Paris. Saint-Ouen. Registres journaliers d’inhumation. Commencé à 27/07/1954 (no. d’ordre 1241); Terminé à 13/11/1954 (no. d’ordre 1841), Archives de Paris, http://archives.paris.fr/s/25/cimetieres-rj. Accessed: 10 March 2021.

- Répertoires annuels d’inhumation. Père Lachaise. Commencé à Keller, Terminé à Lefebvre. Date de début 1940, date de fin 1945, Archives de Paris, http://archives.paris.fr/s/24/cimetieres-ra . Accessed: 10 March 2021.

[i] Аnatolii Volodymyrovych Tarasenko (b. 28 September 1942; Huliaipole) was a Ukrainian and Kazakh entrepreneur, writer, and historian. Honorary Consul of Ukraine in Kostanay (Kazakhstan) [5].

[ii] Fr. "without a profession."

Translated from the Ukrainian and the Russian by Marta D. Olynyk.

Edited by Peter Bejger.