“Intertwined worlds”: In memory of a poet

Sad news has arrived from Kyiv, where on 26 May 2020, the distinguished Ukrainian poet and translator Moisei Fishbein died at the age of 73. With his extraordinary personality and poetic creativity, he embodied the idea of Ukrainian-Jewish understanding and even mutual intertwinement.

“There is no poet of his caliber in Ukraine, nor will there be for a long time to come,” the well-known Israeli translator Viktor Radutzky told UJE. Radutzky is the author of a detailed entry about Fishbein in the Kratkaia evreiskaia entsiklopediia.

Moisei Abramovych Fishbein was born in Chernivtsi in 1946. After being drafted into the Soviet army, he was sent to Siberia. It was in the difficult conditions of his military service that Fishbein began writing poetry, finding a spiritual outlet in the Ukrainian word. He sent these first poems to the distinguished Ukrainian poet Mykola Bazhan, who helped him with his first publication, a selection of poems called “Teplyi podykh” (A Warm Breath), which appeared in December 1970 in the Ukrainian literary journal Vitchyzna.

In 1976 Fishbein graduated from the Kyiv Pedagogical Institute as a philologist specializing in Ukrainian language and literature. Bazhan not only offered the poet moral support but also wrote the introduction to his first collection of poems, Iambichne kolo (The Iambic Circle, Kyiv, 1974). Fishbein, therefore, regarded Bazhan as his literary “godfather.”

In 1979 Fishbein was repatriated to Israel, where his mother was still living at the time.

In 1980–81 Fishbein worked as a correspondent for the Ukrainian literary and sociopolitical journal Suchasnist, which was published by the Ukrainian diaspora in the US and Germany. In 1982 he moved to West Germany, where he was employed at Radio Liberty from 1982 to 1995 as a correspondent, commentator, and editor in the Ukrainian Service and the Russian Service.

In 1984 Suchasnist Publishers in New York issued Fishbein’s book Zbirnyk bez nazvy (Untitled Anthology). Composed of three chapters, it contained 28 original poems, a selection of poems for children, and a large section devoted to his translations from the French, German, Hebrew, Yiddish, Russian, Spanish, and other languages. The book opens with a long introductory article by the famous Ukrainian philologist, Professor Yuri Shevelov, who emphasized the twin aspects of Fishbein’s poetic life: his fate as a Ukrainian poet is indissolubly connected with his Jewishness.

Many of Fishbein’s writings, including articles, interviews, and prose, began appearing in Ukraine in 1989. In 1990 the Kyiv-based publishing house Veselka issued a Ukrainian-language collection of his children’s poems, with parallel translations into Hebrew done by the Israeli poet and translator Manfred Winkler.

In 1996 Fishbein’s collection, Apokryf, featuring poems, translations of poetry, prose, and poems for children, was published in Kyiv. The Ukrainian philosopher and scholar Ivan Dziuba called this book “marvelous and unique, [a publication] that will undoubtedly be included in the golden treasury of Ukrainian poetry.”

Fishbein became one of the main figures of contemporary Ukrainian poetry. Among his other books are Rozporosheni tini (Scattered Shadows, Lviv, 2001), Aferyzmy (Affairisms, Kyiv, 2003), and Ranni rai (Early Promised Lands, 2006).

In Viktor Radutzky’s opinion, Fishbein’s poems recreate the drama of the poet’s spiritual tension, which combines boundless passion for Ukraine’s existence with the “genetic code,” the memory of the Jews’ fate. “His poetry is the encounter between the Ukrainian and Jewish worlds, with their tragedy and pathos. For the first time in history, this encounter took place in the Ukrainian language,” Radutzky says.

Ukraine and Israel, the two fatherlands toward which the poet’s entire being is turned and to which he cannot fail to belong, constantly interact in his poetry with their symbols and myths. Occasionally, the poet began his public appearances in Hebrew, reminding people that his soul also belonged to Israel.

The Jewish-Ukrainian encounter in Fishbein’s work is not simply intoned through the Ukrainian language. The Ukrainian language itself practically becomes the poet’s main hero, and it creates a synthesis of two worlds, the Ukrainian and the Jewish.

In 1990, with Fishbein’s help, Israel became the first country in the world to accept Ukrainian children affected by the Chornobyl catastrophe.

Fishbein was a recognized Ukrainian writer and member of the Union of Writers of Ukraine. For ten years, he was a member of the editorial board of the journal Dnipro and a member of the Ukrainian Center of the International PEN Club. He was awarded the Order of Prince Yaroslav the Wise, 5th class.

In 2002 Moisei Fishbein won the Vasyl Stus Prize, which is awarded for distinguished contributions to culture and for a courageous civic stand. It should be noted that the Taras Shevchenko Prize, which Fishbein so richly deserved, was never awarded to him.

Fishbein was friends with many distinguished Ukrainian cultural figures.

Perhaps Moisei Fishbein may be identified with another native of Chernivtsi: the German-speaking Jewish poet Paul Celan.

The translator Viktor Radutzky thinks that Fishbein possessed perfect pitch and a “marvelous sense of the Ukrainian word that is also evident in his translations of poets from various literatures and which sounded natural in Ukrainian: Heine, Bialik, Celan, Rilke, and Baudelaire.”

Professor Wolf Moskovich, a member of the Board of Directors of the Ukrainian Jewish Encounter, was the first in Israel to write about Fishbein’s work. In the opinion of this Israeli scholar, the poet was an unsurpassed connoisseur of the stylistic riches of the Ukrainian language, and he treated it with immense love and respect.

Fishbein sought to focus on the positive aspects of Ukrainian-Jewish relations. As Professor Moskovich observed, the sacred images of the River (Dnipro) and the Wall (Western Wall of the Temple in Jerusalem)—Kyiv and Jerusalem—are the leitmotif running throughout Fishbein’s poetry.

“He was a person with a good heart who helped people. He was the premier political Ukrainian of Jewish background many years before the Maidan,” Professor Moskovich noted.

I crossed paths with Moisei Fishbein two times. The first time was around 1992–1993 in Kharkiv, where the poet read his poems at a soirée organized by a local Jewish cultural society. At the time, it struck me that I was seeing a rare “tropical bird,” so out of the ordinary did this Ukrainian-speaking Jewish poet sound in then Russian-speaking Kharkiv.

I met with Fishbein a second time in 2008 –2009, when I, an Israeli journalist, was writing about Israeli- Ukrainian bilateral relations.

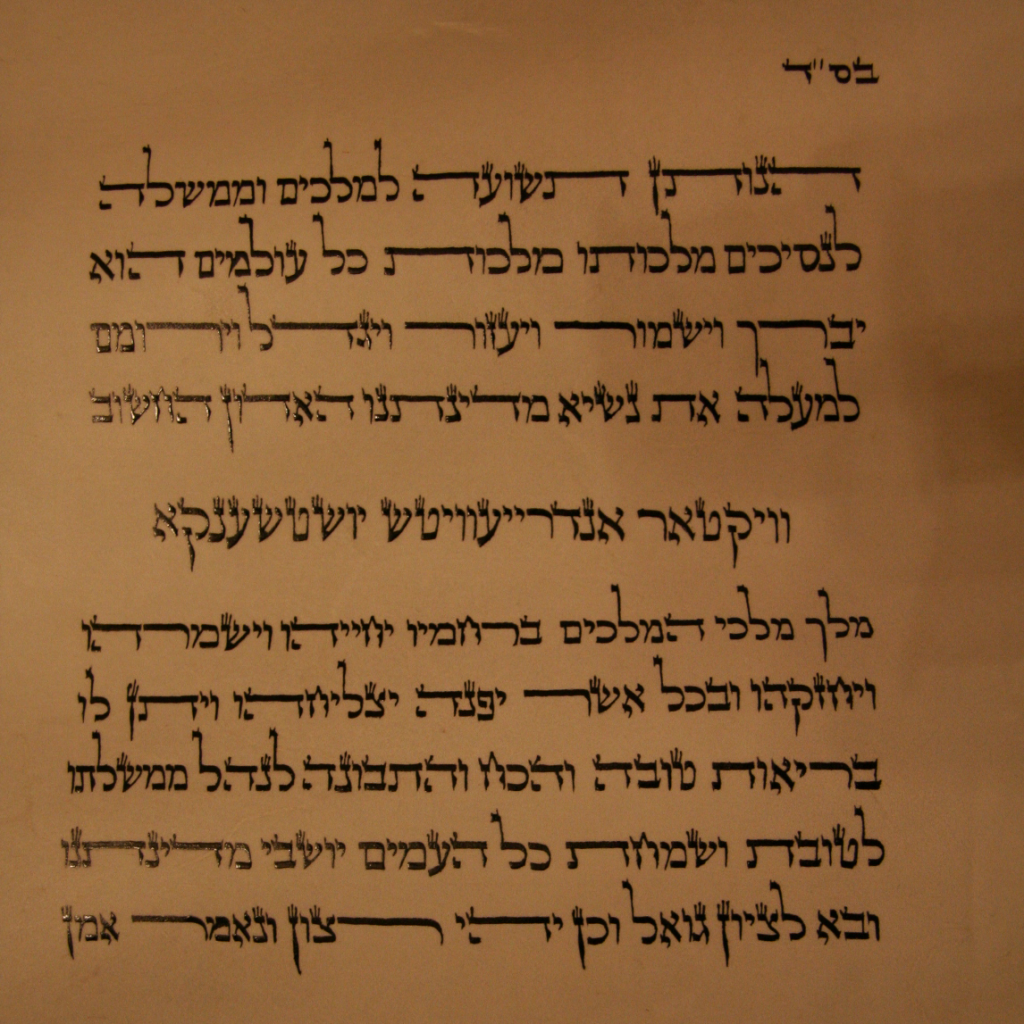

During this period, the poet sent me a photograph of a handwritten Hebrew prayer for the health and well-being of President Viktor Yushchenko, which was written in a Kyiv synagogue at Fishbein’s special request.

I remember another episode. Aware of his connections with the Yushchenko Administration, I telephoned Fishbein, asking him for help to obtain a comment from a representative of Ukraine. The poet agreed to help, adding, however, that this could not be done quickly. “After all, this is a state,” he said. In his words, I heard immense respect and sympathy for Ukraine, which was just starting to build its independent statehood.

At Fishbein’s request, I searched in Israel for any references in Hebrew about the cooperation with the Israel’s foreign ministry of Stella Krenzbach, whose name is connected with the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA), but there was no evidence of such a person anywhere.

Simultaneous membership in two worlds, the Ukrainian and the Jewish, and a sense of the intertwinement of both these worlds did not come easy to him and did not always bring him spiritual peace.

One of Moisei Fishbein’s last poems (2017) begins with a line about the synthesis of two civilizations:

“...worlds have intertwined,

above the unearthly soil,

You will remain one day

between them not with me,

where a tiny, childlike petal melts,

where solitude flows,

universal loneliness,

time flows slowly,

breakages and fractures,

My love for you,

My separation from you...”

Text: Shimon Briman (Israel).

Photos: from the personal archive of Moisei Fishbein.

Translated from the Ukrainian by Marta D. Olynyk.

Edited by Peter Bejger.