Jerusalem idyll: How an artisans’ quarter was turned into a ghetto

Andriy Kobalia: Welcome to the program Encounters. I’m Andriy Kobalia. Today we will be talking about the Jewish history of Vinnystia. Vinnytsia was founded in the fourteenth century and was initially a fortress of the Lithuanian Principality. The first mentions of Jews in Vinnytsia date to 1532. Despite the destruction of the Jews by Bohdan Khmelnytsky’s troops and later by the haidamaks, the Jewish community of Vinnytsia gradually expanded between the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries. In 1897 Jews comprised thirty-six percent of the population. For almost two hundred years the artisan quarter known as Yerusalymka was the heart of Jewish life in Vinnytsia. We will be speaking with the regional historian Anatoly Kerzhner on how this artisan quarter became a ghetto.

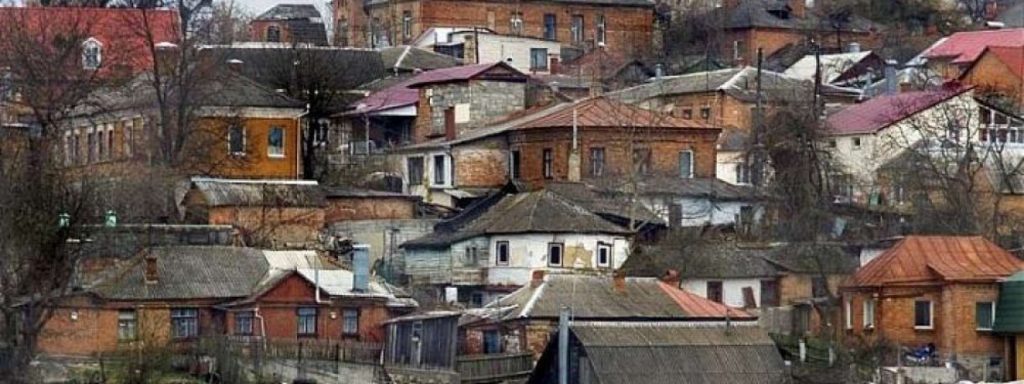

Anatoly Kerzhner: Yerusalymka is a neighborhood in the city of Vinnytsia where mostly Jews lived. Initially, it was an artisan quarter. Over time the number of Jewish inhabitants increased and, as is well known, Jews like to live compactly and to form quarters. The layout of Yerusalymka is very chaotic, and it resembles small Jewish towns throughout Vinnytsia oblast. Even today, if you look at Yerusalymka from the other side of the Buh River, you can see that the current layout repeats the old, chaotic layout, although Jews have not lived there for a long time.

Many historians, and not only Jewish, have noted that the Jewish population of the Russian Empire was very poor. There was only a handful of wealthy Jews. If we look at Yerusalymka from above, we see that it begins from the banks of the Southern Buh, crosses the main streets, then proceeds to the other side of the river. In Lower Yerusalymka there were many small houses, which were more like huts and shacks near the river. This neighborhood was inhabited mostly by poor people. Wealthier Jews lived closer to the center, in Upper Yerusalymka. The residence of Borukh Lvovych was located there, for example. Today it is the oblast radio station. We know that he was one of the principal wealthy people in Vinnytsia. He often provided poor brides-to-be with dowries, and donated money to orphans and the poor. Lvovych was the owner of an iron foundry. Other wealthy people also lived in Upper Yerusalymka. Their mansions can still be seen today on Soborna Street. The Jews of these buildings adhered to a very old and very strong tradition of charitable giving to the community, a tradition destroyed by the Holocaust and Soviet power.

Andriy Kobalia: In the Ukrainian gubernias of the Russian Empire Jews often engaged in trade, in addition to crafts and industry.

Anatoly Kerzhner: In Vinnytsia there were never many major merchants and industrialists, like the Brodskys in Kyiv. Besides Lvovych, there was Bernshtein, the owner of a bank. In those days Vinnytsia was a fairly peripheral city in those years.

Andriy Kobalia: Today there is a café-museum in the city called “Pan Zavarkin i Syn” [Mr. Zavarkin and Son]. Who was this man, and what did he sell?

Anatoly Kerzhner: Originally, his name was Moisei Fligeltub, and he was born in Vapniarka. Eventually he moved to Vinnytsia and set up a shop selling colonial goods, where articles that were rarities at the time were sold: tea, coffee, spices, and other curiosities. But “line five” [the nationality category in Russian internal passports—Trans.] prevented him from further advancement. For that reason he formally accepted Orthodoxy and took the name Zavarkin. Later he succeeded in expanding and managing his business successfully until the revolution. After 1917 he had to flee.

A few years ago a café opened in the building where his shop was once located. It houses a small museum containing old watches, rarities, and items pertaining to Jewish history.

Andriy Kobalia: In the 1920s Jewish religious life was suppressed, and synagogues were turned into warehouses. Zionists were forced to flee, and left-wing Jewish parties could either merge with the Bolshevik Party or disappear. On the other hand, cultural life developed rapidly, and a multitude of books were printed in Yiddish. What was happening in Vinnytsia in the 1920s and 1930s, during the period of NEP and Stalin’s era? Did Yerusalymka change in those years?

Anatoly Kerzhner: After the revolution, life in Vinnytsia changed. During the Civil War the Jews suffered from the constant changes of government, robberies, and pogroms. The excesses of the policy of “war communism” and the pogroms ravaged the Jewish community. The largest pogrom took place on 30 August 1919.

In the 1920s Jewish cultural life flourished. In 1923 departments of Hebrew and Judaic Studies were established at the Vinnytsia branch of the National Library of Ukraine. Unfortunately, these materials are no longer part of the collection because they were shipped out or destroyed during the Second World War. Only the fate of some Torah scrolls that were collected from various synagogues closed by the Soviets is known. This collection contains 250 documents. They were kept for a long time in the Vinnytsia oblast state archives, whose directors were hostile to this material in those years. But the archivists, being professional archivists, found various ways to safeguard them. In the 1980s this collection found a new home and was transferred to the Institute of Manuscripts in Armenia.

In 1926 there were 21,800 Jews living in the city, whose total population was 58,000.

Religious life ground to a halt. Literature was printed in Jewish national sections that spread communist ideology among the national minorities in their native tongue, and which involved them in the building of a socialist society. The newspapers Za bolshevistskie tempy! [For Bolshevik Tempos!], Proletarskaia pravda [Proletarian Truth] Rezets [The Chisel], Krasnaia nit [The Red Thread], and Zvezda [The Star] were also published.

During this period Vinnytsia was home to the Sholom Aleichem Capella and the Gustav Shnel theater group. Jewish elementary and high schools, libraries, and institutes were opened. In 1929 a Jewish section was founded at the rabfak [workers’ university]. However, by the end of the 1930s these activities began to be curbed. Many Jewish communists and cultural activists were arrested in the Terror in the late 1930s.

Andriy Kobalia: During the first months of the Soviet-German war, the [troops of the] Third Reich advanced rapidly through the territories of Soviet Ukraine, and by late fall 1941 a large part of central Ukraine was captured. Vinnytsia was also occupied. Part of Vinnytsia was occupied by Romania but Vinnytsia was controlled by Nazi Germany. What happened to Yerusalymka in the Nazi period?

Anatoly Kerzhner: The Second World War and the the Holocaust is a very painful topic for the Jewish community of Vinnytsia. Nazi troops entered Vinnytsia on 19 July 1941. Two weeks later they began shooting Jews. At first, these were groups of hostages. Then two waves of shootings took place on 19 September 1941 and 16 April 1942. Historians believe a total of around twenty-two thousand Jews were exterminated in Vinnytsia. Yerusalymka, a place where Jews lived compactly, was initially turned into a ghetto; later it became deserted. All those who did not manage to escape are lying in the shooting pits of Vinnytsia. At the present time there are two memorials on Maksymovych and Tolbukhin streets. The shootings took place in the Tiazhyliv neighborhood, near the brick factory, not far from the streetcar depot, past the village of Sheremetka (Pyrohove). After the shootings in 1941 a small number of Jews remained in Yerusalymka.

Andriy Kobalia: You mentioned a part of the Jewish community was shot in the first wave in 1941 and the second wave was in 1942. The second part of the Jewish community remained in Yerusalymka?

Anatoly Kerzhner: Yes, they lived there until the second wave of shootings.

Andriy Kobalia: Who took part in the executions of the Jews?

Anatoly Kerzhner: Regrettably, it should be acknowledged that German Einsatzgruppen carried out the shootings with the assistance of local Ukrainian collaborators who unfortunately went over to the German side and took part in this.

Andriy Kobalia: Martin Pollack has written a book that was published in a Ukrainian translation as Otruieni peizazhi [Poisoned Landscapes]. He writes that Central and Eastern Europe is a place of executions. Practically in every forest in many countries you can find places of execution or other bloody events. And it is very important to remember these places. Where can the “poisoned landscapes” of Vinnytsia be found? Are there plaques explaining that it was specifically Jews who were shot?

Anatoly Kerzhner: I have already mentioned the place next to the brick factory and the shootings near the streetcar depot, as well as in the village of Pyrohove. If we’re talking about the politics of memory in Vinnytsia, not everything is going all that smoothly. There are two memorials: on the premises of Zelenbud, where there is one monument. People gather there twice a year in order to honor the memory [of the victims]. The other one is on Tolbukhin Street, where there is also a fence.

But the majority of the population is not aware of all the remaining sites. To this day researchers have not been able to determine the location of the grave near the village of Pyrohove, on the way to the village of Medvezhe vushko. According to records, more than a thousand Jews were shot there. But the exact place is not known. There is nothing, no plaques at all next to the depot and the brick factory. This is bad and I hope that enthusiasts and volunteers, with the government’s assistance, will change the situation. For example, it was announced recently that appropriate signage will be installed from Khmelnytsky Highway to Maksymovych Street, indicating that there is a memorial there. An information stand with accounts of the city and photographs will also be set up to inform people about the frightening events that took place at these locations.

Andriy Kobalia: We have been talking with Anatoly Kerzhner about the Jewish history of Vinnytsia.

This program was made possible by the Canadian non-profit organization Ukrainian Jewish Encounter.

Originally appeared in Ukrainian (Hromadske Radio podcast) here.

Translated from the Russian by Marta D. Olynyk.

Edited by Peter Bejger.

NOTE: The UJE does not necessarily endorse opinions expressed in articles and other materials published on its website and social media pages. Such materials are posted to promote discussion related to Ukrainian-Jewish interactions and relations. The website and social media pages will be places of information that reflect varied viewpoints.