Jewish culture as part of Ukrainian heritage: interview with researcher Khrystyna Semeryn

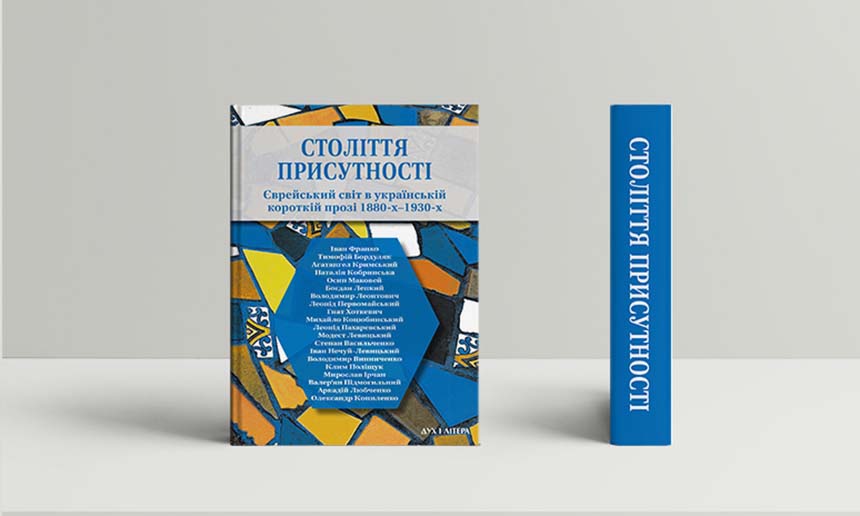

Jewish culture has become a part of Ukraine and is reflected in literature, among other things. Dr. Khrystyna Semeryn, a journalist and essayist, edited the anthology A Century of Presence. The Jewish World in Ukrainian Short Prose, 1880s–1930s.

Jewish culture and its interaction with Ukrainian culture

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: Today, I am delighted to welcome our guest, Khrystyna Semeryn, who wrote a fascinating dissertation entitled The Jewish World in Ukrainian Short Prose of the Late 19th and Early 20th Centuries. Mythopoetics, Imagology, and Aesthetics. Before discussing your research, let me ask you a few introductory questions: Why did you decide to focus on this topic? What attracted your interest? Why Ukrainian short prose and this particular period?

Khrystyna Semeryn: Actually, I didn't focus on this one topic. It's a reflection of my broad interests. The title of my thesis points to the intersection of many of these interests: not only short prose and literature but also culture in a broad sense, and not only Ukrainian culture but also the culture of the region known to us as Central and Eastern Europe. As far as the term imagology is concerned, it refers to research into and discussions about how we see ourselves and others in this world and how we talk and think about other cultures.

In fact, this is the basis of our perception of ourselves and others, which unfolds into a panorama of very different, complex phenomena that are difficult to comprehend. This can be briefly defined as a conversation about what is our own and what is not. When we imagine ourselves, we understand that there is someone else opposite us. Depending on our historical, cultural, and social context and era, we can imagine those others as equal, intrinsically valuable, interesting to us, and different from us. Alternatively, we can imagine them as strangers, to a certain extent, hostile and dangerous and build our interaction and communication with our vis-à-vis, with this culture, country, and people on other grounds.

Going back to what you asked about interest, I am actually interested in cultures, how we talk and think about other cultures, and how this happens in culture, literature, and art. That is why I constantly work with entirely different stories and different types of art, texts, and cultures.

My interests are focused on those cultures that are next to us and have coexisted with us for centuries. Jews have lived in Ukraine, and Jewish culture is part of Ukrainian heritage. We have interacted extensively and lived together in the same space, time, and social and historical plane — in fact, in one diverse and multifaceted space. For me, this topic grows out of all these interests in our diversity and multiculturalism. It is also an attempt to tell and explore more of multicultural interactions and encounters between Ukrainians and other peoples who have lived next to us.

On the Century of Presence anthology

"Fragments of a lost mosaic"

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: Thinking about other cultures happens all over the world. Does your research suggest that our experience could be special in some way? Are there any aspects that make us unique? Obviously, every experience is unique.

Khrystyna Semeryn: You have actually answered your question briefly at the end. Every experience is indeed unique and cannot be replicated. Everything I write about interactions and heritage in the broadest sense concerns the description of an attempt to inspect and discuss the uniqueness of our experiences, encounters, and interactions with others. Just as I write about Jews, I discuss, for example, the heritage of German colonists in Ukraine, and every time it's about some new conversation, new perspectives, and unique experiences. So, I wouldn't attempt to single out something distinct because everything we talk about is essentially specific to our context, culture, and history.

Another thing is that the coexistence of Ukrainian and Jewish cultures was so close, and this interaction was so important that it directly influenced how we were shaped, who we are today, and how we perceive ourselves. Fortunately, we are now discussing and reclaiming our past, including our recent past. We are trying to consider all these fragments of the lost mosaic — everything that was silenced, repressed, and suppressed in our memory. A distinctly important aspect for me is not only articulating this uniqueness of experiences and exploring them but also trying to reclaim the lost fragments of memory and articulating the multitude of existing connections that are not always noticed and known.

We are talking about two related works. One is actually a study, while the other is an anthology from the Dukh i Litera publishing house.

In the anthology, I strive to tell about the complexity of all the interconnections in the footnotes and small introductory essays. I explain how names, dates, and events appear on our grand cultural and historical tapestry, how people intersect in time and space, and what cultural influences arise from these encounters.

This is, in essence, the topic of our conversation and my research on short prose and literature in general. It is also the topic of the anthology, my research into art, and everything I write and talk about.

On the authors in the anthology

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: What authors are included in the anthology, and what kind of prose is represented?

Khrystyna Semeryn: The topic covers the period from the 1880s to the first third of the 20th century. This is due to a combination of historical, social, and literary circumstances, as it was a time of social transformations and changes on the political map. It was also a time of certain literary transformations as the genre of short prose gained new relevance, developing in the European context and beyond. Accordingly, it was also on the rise in Ukrainian literature.

This period, about half a century, covers several generations of writers from all parts of Ukraine, who were in different empires and countries at the time but created the fabric of modern Ukrainian literature as we know it. The anthology begins with Ivan Franko, and I discuss the writers of his generation. We move on to the writings of the early 20th century and authors who embraced modernist aesthetics. The anthology ends with Kharkiv-based writers. It is a voluminous and varied selection of texts and writers showing the diverse ways of depicting Jews and the Jewish world in Ukrainian literature.

The feminist perspective and secularization in literature

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: In the "Encounters" program, we discussed the Rudnytsky family, which was a mixed marriage. For some reason, I was internally outraged at the fact that the woman, Milena Rudnytska, had to convert to Christianity to marry her man, Mykhailo Rudnytsky, and start a family. I know you studied this phenomenon, among other things. What other key points could you highlight? Was it more often the woman who had to make an adjustment?

Khrystyna Semeryn: This is an important focus of the anthology and my work. I work with the feminist perspective, so I could not ignore what I call secularization and women's emancipation. It is one of the main lines I try to explore in literature. Naturally, literature reacts to changes in social life, and social life does not change as quickly and easily as we would like. That is why we see plots that overlap to a certain extent, creating a tradition of depiction, albeit a small one. In this tradition, a woman indeed converts to Christianity, makes concessions, and renounces not only her religion but also her people.

This is how other protagonists perceive the situation, too. The anthology includes two stories by male authors, "Beyond the Walls" by Stepan Vasylchenko and "A Shameful Deed" by Klym Polishchuk. They describe women trying to free themselves from the pressure of the patriarchal community and what the authors consider outdated traditions and life patterns. And they do it through secularization, more precisely through conversion to Christianity. So, on the path to a secularized life and gaining freedom, they follow this scheme of joining the Christian society.

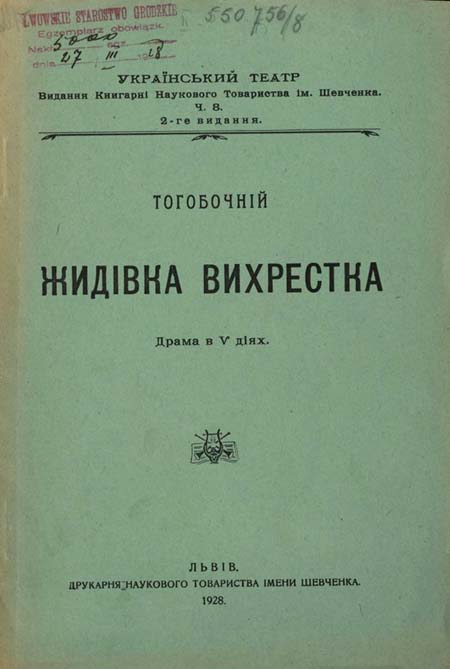

The plot about a Christianized woman in literature

Khrystyna Semeryn: In fact, this plot was quite popular. Ivan Tohobochny's melodrama with the plot about a Christianized Jewish woman is, I believe, a stage on the path towards the depiction of women beyond the patriarchal system and stereotypical images. That's how Ukrainian literature developed the topic at one time.

Milena Rudnytska, who was born into the family of Ivan Rudnytsky, the son of a Greek Catholic priest, and Ida Spiegel, a Jewish girl, became a feminist and a well-known Ukrainian feminist, journalist, and public figure. So, I think that the step that Ida Spiegel took was not stereotypical. On the contrary, it was the decision of a woman who made up her mind to change her life and embrace this path. In this sense, this example differs from what we find in literature, which works with stereotypical images and tradition. Thus, changes in literature occur a bit differently than in society.

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: Have you come across any cases where a man had to convert to Judaism, and it was reflected in literature?

Khrystyna Semeryn: I have not seen cases like that in short prose. Again, this is the influence of the literary tradition. And the tradition was that women converted to Christianity.

Jewish culture and the topography of memory

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: You have also studied the topography of memory, Jewish locations and spaces, and their reflection in literary images. Could you speak about this aspect?

Khrystyna Semeryn: That's an excellent question. What we call the topography of memory or imaginary geography is one of the most important parts of my work and one in which I take great interest. It's how our presence and that of the people who are no longer with us are reflected in space. It's about how space remembers, and we remember through space. Literature plays a huge role here, shaping these spaces and our perception of the surrounding landscapes. It makes a significant contribution to what we call the itineraries of memory.

This is not directly related to short prose but links up to our contact and literature in general. There was this Jewish poet, Zuzanna Ginczanka, who was born in Rivne and died during the Holocaust.

She lived in Lviv for a while and in Warsaw, where she became a Polish poet. Her name was restored to the public not so long ago, and it was accompanied by marking the spaces where she lived, which became a tradition. People tried to recreate Ginczanka's landscapes and itineraries, and walk where she could have walked.

We actually have many cases when literature and our geography intersect. Through literature, people try to find traces of memory about communities, people, local events, and things that are no longer there. They search for traces of presence, so I focused intently on this aspect in my research.

Attention to small settlements

Khrystyna Semeryn: Personally, I am fascinated by the fact that short fiction paid so much attention to completely different places, particularly towns and villages, even those where the last traces of [Jewish] presence are long gone. Thus, villages only appear on our imaginary maps because authors write about them. I take special interest in discussing not only cities that are always present in literature, our imagination, and our understanding of the world, but also some marginal ones that we remember because they are described in a short story. I will give you one example. Tymotei Borduliak was a priest who also worked the land. He was quite poor, worked hard, and educated his parishioners, opening Prosvita centers in the villages where he was a priest. Borduliak wrote a story about a poor Jew. To explain its context, I mention Radetzky March, a novel by Josef Roth, a Jewish writer and a Brody native, which mentions the village Borduliaky, where Tymotei Borduliak was born and raised.

So, Joseph Roth describes this tiny village a few dozen kilometers away from Brody and keeps it in memory through literature. We can now read about a Jew in Borduliak's short story, remembering these parallels, grasping these allusions, and developing a deeper understanding of space and the topography of memory.

This program is created with the support of Ukrainian Jewish Encounter (UJE), a Canadian charitable non-profit organization.

Originally appeared in Ukrainian (Hromadske Radio podcast) here.

This transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

Translated from the Ukrainian by Vasyl Starko.

NOTE: UJE does not necessarily endorse opinions expressed in articles and other materials published on its website and social media pages. Such materials are posted to promote discussion related to Ukrainian-Jewish interactions and relations. The website and social media pages will be places of information that reflect varied viewpoints.