Jewish Kultur Lige (1918-1924), its legacy, and world-famous members

This episode of the Encounters program is about the Kultur Lige, a Jewish secular cultural and educational organization that was founded in Kyiv and operated in 1918-24.

The program's guest is Leonid Finberg, a sociologist, cultural researcher, director of the Center for the Studies of History and Culture of East European Jewry, editor-in-chief of the Dukh i Litera Publishing House, and member of PEN Ukraine.

How the Kultur Lige was established

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: Our topic today is the Kultur Lige (Culture League). It seems to be an underestimated phenomenon. So, we'll be talking about its activities in the 1920s.

Leonid Finberg: Starting from 1918.

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: And its influence on cultural life, especially on Kyiv's Jewish community at the time. What kind of social and cultural organization was the Kultur Lige?

Leonid Finberg: It was established in 1918, after the first revolution, to promote Yiddish culture in every possible way. In a way, it operated as a large "Ministry of Jewish Affairs" during Ukrainian independence in those years. The organization was centered in Kyiv, where its leading bodies were concentrated.

The Kultur Lige had branches in nearly all cities of Ukraine despite the turbulent events of the time. This association organized the operation of schools, libraries, bookstores, and book publishing, i.e., all spheres of culture that were developing at that time. Some circumstances contributed to the situation because a lot of intelligentsia from other cities in what was Russia at the time came to Kyiv, fleeing from the Bolsheviks. I should note that there were many Jewish cultural centers in Kyiv even before that. The Kulur Lige worked the same way as similar Ukrainian structures. Its activities were quite fruitful. They became the object of research only recently, during Ukraine's independence. All this was hushed up in Soviet times for obvious reasons.

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: Who were the specific organizers and the main driving figures? Or was it the effort of many people, making it difficult to single out individuals?

Leonid Finberg: Political and cultural functions were very closely intertwined in political life at the time. This contrasts with our times when government structures ignore culture almost entirely. Back then, the members of mostly left-wing, socialist parties supported cultural activities and tried to promote culture as much as possible. At that stage, folk culture and Yiddish culture were the focus of attention, but all the areas I've mentioned experienced active and fruitful development.

A system for developing Jewish culture

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: Did any of these directions prevail? Was it a kind of concerted work?

Leonid Finberg: There was an entire system for creating and developing Jewish culture in those times. Different directions intersected and complemented each other. Authors wrote for publishers, and publishers brought out their works. Many of those cultural figures taught in schools, held meetings in libraries, and organized exhibitions. Apparently, there were some contradictions, but it was still a fairly powerful integrated mechanism.

The prevalence of some directions over others became apparent only later for various reasons. The activities of the Kultur Lige were not studied for a long time and were almost unknown, just as they are little known now. That is why we know little about what was done in the field of schooling or libraries. However, my colleague Ania Umanska is now writing a thesis on these activities of the Kultur Lige, so I hope we'll soon know a lot more.

Over time, the works of the Kultur Lige artists received increased visibility largely thanks to the activities of the Israeli researcher Hillel Kazovsky and the Paris Museum of Jewish Culture, as well as the joint efforts of our center and the National Art Museum. People who studied in those schools or read books in those libraries are long gone. In contrast, many artworks created in those years have survived.

The Kultur Lige was the most powerful center of artistic Jewish culture in Eastern and Central Europe (it later worked in Warsaw, Moscow, and Romania) and even in Western Europe in later years. However, those were the organization's remnants, while its most active period was in Kyiv. Some of the artists who worked here later became world-famous, while their beginnings were connected with the Kultur Lige in one way or the other.

Kultur Lige in Kyiv

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: How long was the Kultur Lige active?

Leonid Finberg: For about six years, from 1918 to 1924, in Kyiv and on the territory of Ukraine. Then came the Bolsheviks, who replaced the leadership and started fighting against manifestations of national culture. They wanted to see only proletarian culture while simplifying and destroying the things done by their predecessors, who were much better educated. By then, many of them realized they had to part ways with the Bolsheviks. So, they scattered around the world, going to Berlin, Paris, or elsewhere. The Kultur Lige was active for six years in Ukraine and more than a decade in a broader sense.

Kultur Lige served the large Jewish population of Kyiv

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: Were Kultur Lige centers analogous to our present-day communities with specific locations where you can meet people and socialize?

Leonid Finberg: Absolutely. Those Kultur Lige centers were precisely that. Multiple centers operated in different cities, playing exactly the role you have described.

For example, the Kultur Lige mounted an exhibition of Jewish art in Kyiv. Its publishing house brought out books and invited artists to illustrate them. Some 150 books, printed on poor-quality paper, have survived. Of this number, 20-30 have excellent illustrations, and we will put them on display in the Museum of Book History if everything goes well. An exhibition dedicated to 1,000 books by our publishing house is scheduled for April-June, and some of these books discuss Kultur Lige art.

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: Did the Kultur Lige have anything like the head office?

Leonid Finberg: Yes. There are buildings in Kyiv where the Kultur Lige kept offices, and its leaders met. Unfortunately, they still lack memorial plaques, just like many other sites of important events in Ukrainian, Jewish, and Polish history. It's another debt that we have before those who lived back then.

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: What is this building located if it still stands?

Leonid Finberg: It's located on Velyka Vasylkivska Street, at the intersection with Saksahanskoho Street. This is where the Kultur Lige had an office. There was another one in Khreshchatyk and elsewhere. The Kultur Lige was quite an extensive structure that was responsible for many affairs. And, the Jews then made up a significant part of Kyiv's population.

Kultur Lige's art

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: What about the art produced by Kultur Lige's members? Who were those artists?

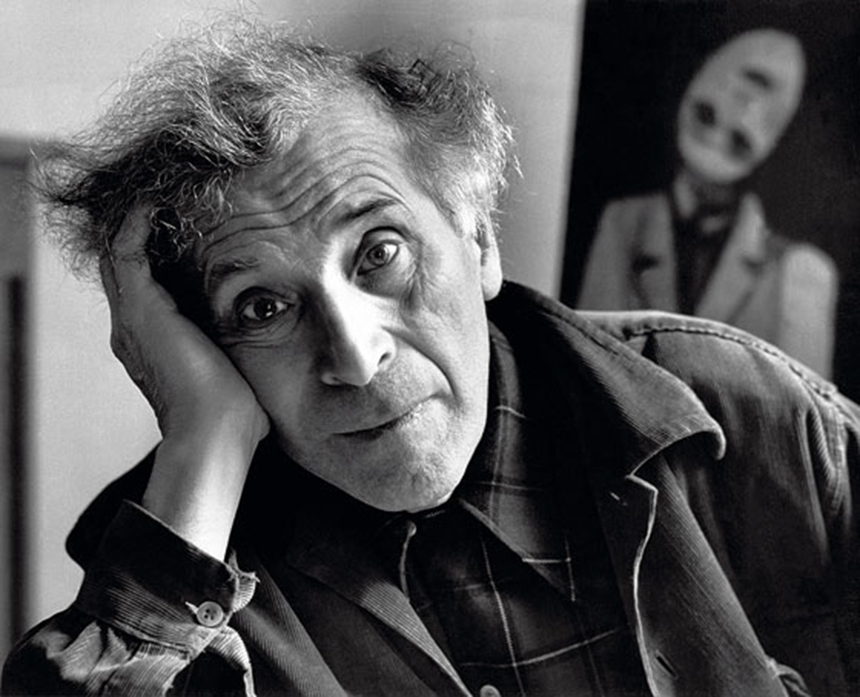

Leonid Finberg: There are several aspects here. First, no one knows that one of the first books illustrated by Marc Chagall was published in Kyiv in 1922. It was a book by David Hofstein, a Jewish writer who wrote in Yiddish. We have this book and will put it on display at the forthcoming exhibition.

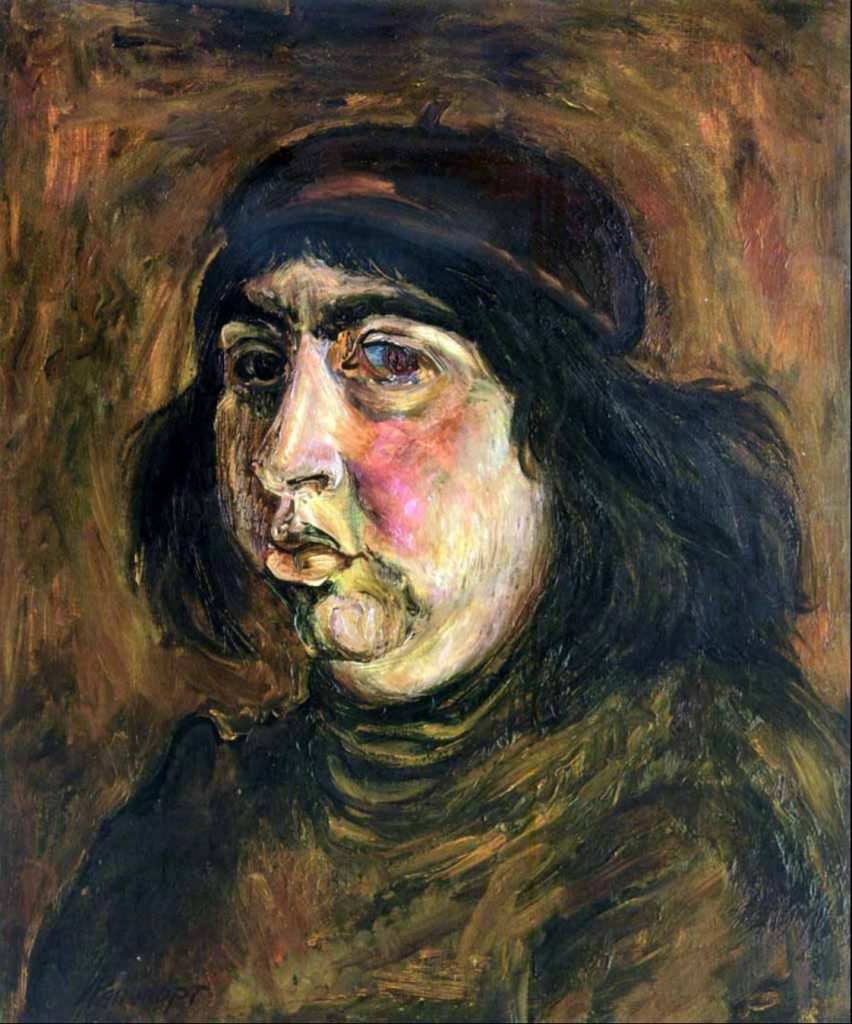

The Kultur Lige's book program also included books illustrated by Mark Epshtein, one of the few artists who stayed in Kyiv. However, his works became less interesting in the later period, in the 1930s, like those of many other artists who were forced to adopt socialist realism. But here we are talking about many artists who illustrated books by Peretz Markish and belonged to the Kultur Lige, as well as about the brilliant sculptures of Joseph Chaikov. The originals have not survived, but there are photographs of them, and we have reconstructed them in a stunning fashion. I think these reconstructed sculptures will also be presented at the mentioned exhibition.

There was quite a large overlap with Ukrainian artists of that time, namely with the Boichukists [followers of Mykhailo Boichuk. — Trans.]. There were art schools where Ukrainian and Jewish artists studied together. Upon graduation, they all went their separate ways, of course, but just like the Boichukists embodied and shaped Ukrainianness in art, these Jewish artists formed the Jewish national style — more precisely, styles as there were many of them — in the art of that time.

We are talking about many artists who later became world-famous, such as Chagall, Robert Falk, Kritin, the theater artist Rozalia Rabynovych, and many others. Both Nathan Altman and El Lissitzky were involved in the Kultur Lige. I will not recount the names because they will not tell our audience much, but I invite you to the exhibition I've mentioned. Those who saw the exhibition in 2006, when we did it at the National Art Museum, remember it well. It was a shock and discovery for all Ukrainian art lovers.

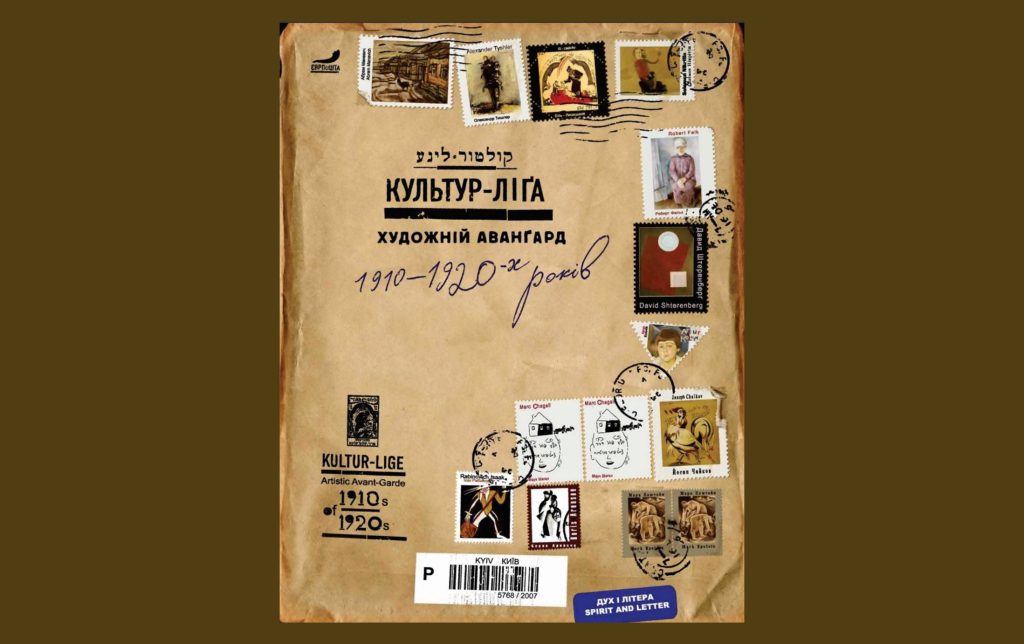

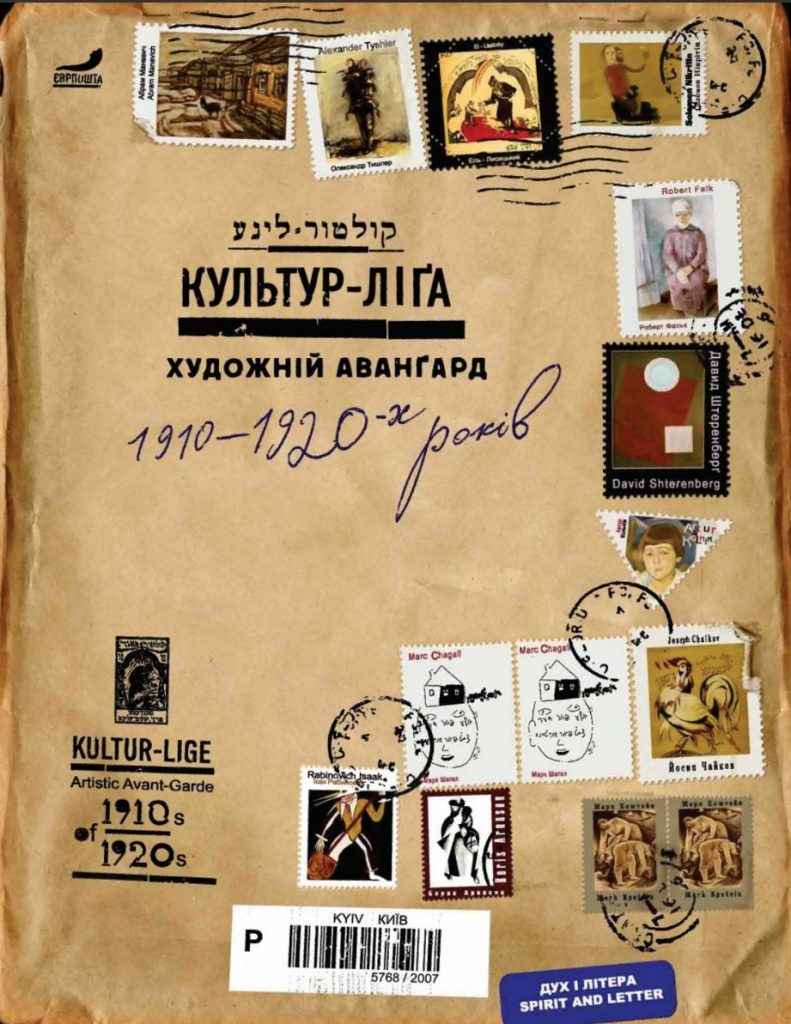

Kultur Lige album catalog

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: In addition to the planned exhibition, you have published the Kultur Lige album catalog. Is it already available?

Leonid Finberg: Yes. We published the album catalog, and a similar edition came out in Paris. They are not to be found anywhere else in the world.

The Kultur Lige did not release an album of this kind in its time because albums were not published in those years. First, good color printing was not available in our lands. Second, they didn't have the resources and time to prepare and publish them. We have released not one but two such catalogs.

One catalog represents sculpture, painting, and graphics by the Kultur Lige artists, and the other one contains only graphics. We have run out of copies of the first edition, but the second book, Hrafika "Kultur-Ligy" (Kultur Lige Graphics), is still available. Those interested in Ukraine's art and all serious art critics know this book. We presented it at various forums and gave copies as gifts to libraries. In short, it is known to an extent but not enough to be familiar to the general public.

Most importantly, much effort is being made to present Ukrainian culture to the world, but many names are unknown for obvious reasons. So, telling the world about the Kultur Lige phenomenon is essential. There is a war raging on in Ukraine, and the COVID-19 pandemic preceded it. Nonetheless, we keep our hope alive and do what we can to help bring victory. After that, we will continue our studies and efforts to tell the world about this phenomenon.

A lost legacy

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: I understand that there are many unexplored aspects of the Kultur Lige's activities. Do we have sources for this exploration? Many things might have been lost.

Leonid Finberg: Indeed, a large part of Ukrainian and Jewish culture has been lost. We know the tragedy of losses. At the same time, we are aware of what has survived through these decades in Ukrainian museums and private collections. The graphics and a good deal of paintings are especially well preserved. Nevertheless, one of the best collections of Robert Falk was in Donetsk, and it does not belong to us today.

However, many works have survived, and given interest and opportunity, they can be presented in Paris, London, Kyiv, and Warsaw. We would need patrons to become involved and organizations to take an interest, and we would do it, continuing our ongoing efforts as best we can. Our greatest desire is to tell Ukrainian readers and viewers about the Kultur Lige, and I hope opportunities will present themselves.

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: What about the generational legacy of the Kultur Lige? You've mentioned Peretz Markish, who is an outstanding personality. Meanwhile, his descendants are no less outstanding.

Leonid Finberg: It's true. In general, we have done a lot to popularize Jewish studies, particularly the art of the Jews among the Sixtiers and those who were active in the subsequent decades. Many painters among them belong simultaneously to Ukrainian and Jewish cultures.

Kyiv collection

These artists are little known abroad but enjoy certain popularity in Ukraine. I mean Olga Rapay-Markish, a brilliant sculptor who made 3,000 sculptures in her lifetime. Her works can be seen on the premises of some institutions, including a children's library in Kyiv. Her legacy has been preserved by collectors and descendants.

Other names include Zoya Lerman, Liubov Rapoport, Mykhailo Weinstein, and the list continues.

At some stage, we realized we had a chance to present a phenomenon that did not exist in other countries or was much less developed or manifested there. We could present Jewish art of Ukraine's independence or the late 1980s when there was more freedom for art in the country. And we did it.

Our Kyiv Collection album contains works by the artists I've mentioned and a dozen whom I have not named. In my opinion, they produced exciting art that is still almost unknown worldwide. The same can also be said about Ukrainian artists who were active in the 1960s and the 1980s. For well-known reasons, we had next to zero opportunities to present them abroad.

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: It's great that these amazing works are now being restored from oblivion. Mr. Finberg, thank you for this conversation and your work. I sincerely believe in the importance of this cause.

Leonid Finberg: I, too, believe in the importance of this cause, and we continue to do what we consider important. If all things fall into place, we hope to present much of what we've discussed at the One Thousand Books exhibition of our Dukh i Litera Publishing House. We'll be able to include art, children's books with exciting illustrations, and excellent books on culture that describe, in particular, Ukrainian cultural figures. This is based on our understanding of Ukrainian culture as the culture of a political nation that includes not only ethnic Ukrainians but also Jews, Poles, and Crimean Tatars. The same is true of other philosophical and historical books. We work as hard as possible but still cannot believe our publishing house can celebrate its thousandth book.

Kultur Lige ( קולטור-ליג, Culture League) was a Jewish secular charitable and cultural-educational organization that operated in 1918-1924. It was created at a time when the Central Rada ushered in the "renaissance of the nation" era and proclaimed national and cultural autonomy for ethnic minorities.

The league was divided into several sections: literature, music, theater, painting, sculpture, folk schools, preschool education, and adult education. It was governed by the Central Committee of 21 members who met monthly and elected the Executive Bureau (7 members, weekly meetings) to handle day-to-day operations. Branches were formed throughout Ukraine: 27 as of the summer of 1918 and 120 by the end of the year. Some branches also emerged outside Ukraine. According to its charter, the Kultur Lige aimed to develop and popularize ethnic secular culture among ordinary Jews; promote all kinds of art, such as literature, painting, music, and theater; and facilitate the construction of a new Jewish democratic school and other educational institutions.

This program is created with the support of Ukrainian Jewish Encounter (UJE), a Canadian charitable non-profit organization.

Originally appeared in Ukrainian (Hromadske Radio podcast) here.

This transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

Translated from the Ukrainian by Vasyl Starko.

NOTE: UJE does not necessarily endorse opinions expressed in articles and other materials published on its website and social media pages. Such materials are posted to promote discussion related to Ukrainian-Jewish interactions and relations. The website and social media pages will be places of information that reflect varied viewpoints.