"Jewish Responses to the Holocaust: Dispossession, Restitution, and Reconstructing the Home": An overview and reflections on a seminar held at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

The following article recapitulates the proceedings of the seminar "Jewish Responses to the Holocaust: Dispossession, Restitution, and Reconstructing the Home" held on 8–12 January 2024 at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. The author of the overview was the only seminar participant from Ukraine. Thus, in his text, he not only reflects on the question of the loss of home, dispossession of Jewish property during the Holocaust, and restitution but also raises similar questions caused by Russia's criminal actions in Ukraine.

26 April 2024

Yurii Kaparulin

The 2024 Jack and Anita Hess Faculty Seminar entitled "Jewish Responses to the Holocaust: Dispossession, Restitution, and Reconstructing the Home," intended for North American university lecturers, was held on 8–12 January 2024 at the Jack, Joseph and Morton Mandel Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

On the eve of the seminar, the organizers asked the participants to share their thoughts about the seminar topic by replying to a number of questions. Below is the list of questions and my answers to them:

- Given that a vast number of people not only lost their property but also perished during the Holocaust, what difficulties do we, educators, encounter when lecturing on material losses and the process of restitution?

Human life is the highest value. A lost life cannot be restored or measured in material terms. However, today, many jurists say that compensating the victims of mass violence, or their relatives, is one of the first conditions of the successful process of satisfying and restoring justice. It is inevitably accompanied by moral dilemmas experienced by victims or their relatives, who find it difficult to accept such compensation, viewing it as an attempt by yesterday's criminals "to buy them off." On the other hand, the latter (states, groups, or individuals) are not always prepared to offer material compensation. So, when we work with students, it is important to emphasize that a life lost is not equal to compensation, and restitution is part of the transitional justice period.

- The Nazi policy of dispossession of property differed markedly in Eastern and Western Europe and depended on various national contexts. How can we convey more effectively this diversity of experiences regarding the loss of property during classroom work?

In examining these questions, we must definitely take into account the context of a specific country, as well as its prewar and postwar policies. Recently, I wrote about the loss of property experienced by Jews from Soviet Ukraine, who were left without their homes when they were evacuated to the eastern part of the USSR in 1941. However, when some of them returned after the Nazis were expelled in 1944, they learned that their properties, especially real estate, were now in the hands of new owners: Soviet functionaries, resettled people, or simply local inhabitants. In many cases, they refused to return their newly acquired property (for a detailed discussion of this question, see my article in the section "Overcoming the Past").

- In what way can teaching the history of dispossession and restitution change our ideas about the timeframes of what is traditionally called "Nazi Germany and the Holocaust"?

From the standpoint of material reparations, the consequences of the Holocaust are still felt today. For example, in working on eyewitness testimonies in the Visual History Archive, most of which were recorded in the 1990s, I noticed that individual respondents learned about the possibility of obtaining reparations only at the end of their lives after the collapse of the USSR. Throughout its entire existence, the Soviet Union pursued the policy of rejecting the uniqueness of Jewish suffering during the Holocaust, thus restricting access to international compensation programs.

The work of the seminar

The first day of the seminar was devoted to getting acquainted and discussing key concepts. The issue of "agreeing about terms" was not redundant because there are often fundamental differences in scholars' treatment of individual, basic concepts. For example, depending on the disciplinary and regional focus, the concepts of "restitution," reparations," and "home" can have differing interpretations. The definitions from the Encyclopedia of Transitional Justice were used to define the first two terms. [1]

We began the discussion of "home" from its meaning as some form of real estate that people lost in the wartime conditions and the Holocaust. A better understanding was achieved by discussing Shannon Fogg's article about the housing crisis in France during the Second World War. The historian pointed to the central place of housing problems during the Holocaust, revealing the participation of individuals in the expulsion of Jews in the light of interwoven economic, ideological, and geographic motives. [2]

Then, we focused on analyzing photographs, including those taken by private individuals before the war and those taken by the German authorities as they documented the process of robbing Jewish property. We also analyzed the lists of items removed from homes, which were created by private individuals (mostly Jews) before dispossession or by survivors who tried to regain their lost property after the war. I got a photograph of a warehouse with packaged sets of household items, including dishware packed in dozens of the same type of boxes. These were likely items seized from the homes of Jewish families who had prepared them for a future sale or distribution among the non-Jewish population of Austria and Germany. Leora Auslander's article about Holocaust lists and inventories helped us understand the context of the photographs, which we had little information about. [3] The study was based on the stories of surviving Parisian Jewish families, whom the new French government permitted to regain their stolen property but demanded lists with an accurate description of items and their quantities.

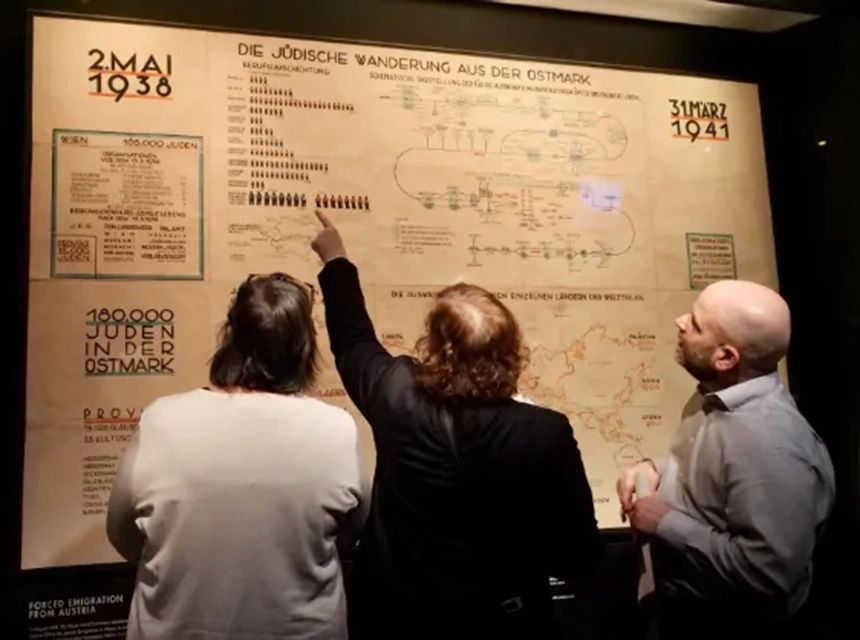

The second day of the seminar was devoted to the Holocaust in Austria. We examined the experience of Austrian Jews and the characteristics of their perception of home. A substantial number of Jews were deeply integrated into Austrian society before the Second World War. Still, most of them ended up in the same discriminatory conditions as the Jews of Germany after the 1938 Anschluss. Several tens of thousands of people were forced to leave their homes and evacuate to safer countries. Some continued to identify with Austria and sought to return to that country at the first opportunity. Upon returning home after the war, they saw people living in cities partly destroyed by the bombings and, like everyone else, experiencing many difficulties, in particular, because of the housing crisis (the lack of apartments and houses) and food shortages. Jews in postwar Austria often encountered antisemitism and contempt from the non-Jewish residents of Vienna. The latter began identifying themselves with the image of the Nazis' "first victims," which was nurtured in postwar Austria on the collective level. We discussed these and other questions with Elizabeth Anthony, USHMM associate and author of a recently published study about Viennese Jews. [4]

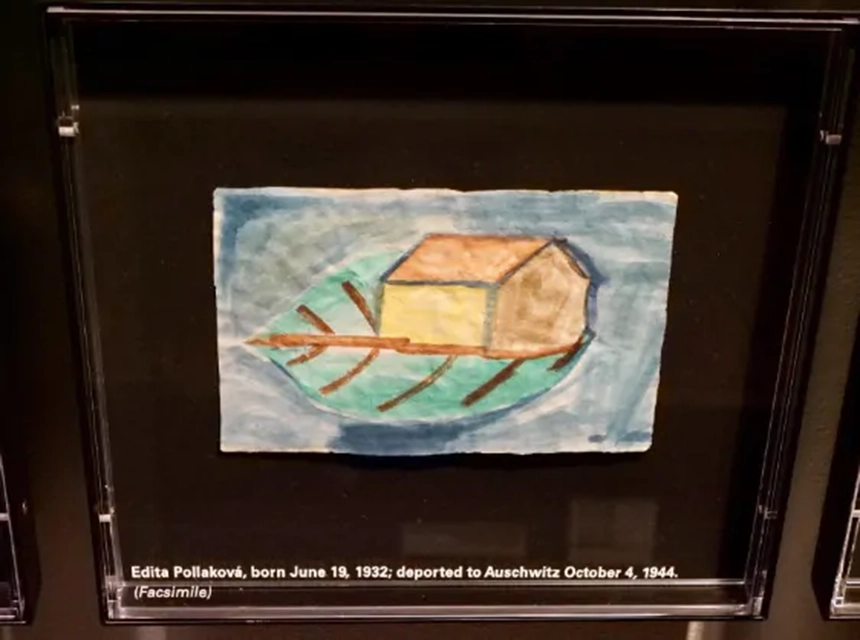

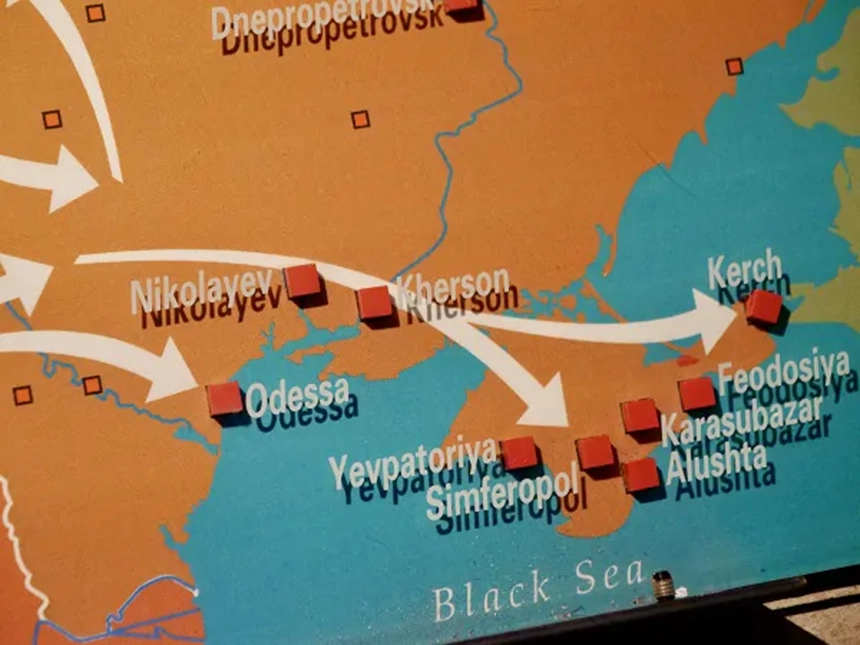

The second day of the seminar was also devoted to the testimonies of Holocaust survivors stored in the collections of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. We tried to find a description of the concept of home in their ideas and narratives. At the end of the day, there was a visit to the museum's permanent exhibition, during which the seminar participants focused on exhibits dealing with the topic of displacement, loss/return of a home, and property. One of the key exhibits was a map showing the transnational scale of the Holocaust through statistics revealing the departure of Jews to other countries.

The third day of the seminar was dedicated to the landscapes of the Holocaust and resettlement. The foundational study here was Tim Coles' book Holocaust Landscapes. [5] The seminar participants explored how the experience of displacement destabilized people and was used as a tool for participating in the genocide. Cartographic instruments helped research the Holocaust, and the online resources Holocaust Geographies Collaborative and EHRI Geospatial Repository proved to be invaluable aids during the seminar. The participants familiarized themselves with USHMM Experiencing History, a digital instrument used in studying the Holocaust with the aid of primary sources. Then, we got together in small groups to discuss specific thematic cases in the collections of the USHMM pertaining to the question of home and displacement.

"In Kherson was the first time when I found out that I was a Jew"

Our final activity on the third day of the seminar included a lecture and discussion of the work of Anna Cichopek-Gajraj about the return home in the Eastern European context using the methods of oral history and the comparative perspective. In her research, the author emphasizes that the word "return" means that a person definitely returns to something near and dear in their homeland. However, the postwar "return" of Jewish survivors lacked any features of such closeness. They did not find anything familiar in the physical and social landscapes of postwar Eastern Europe. For example, the wartime destruction and human losses had markedly changed Poland and Slovakia. Survivors themselves were not the same as before. The experience of genocide changed them forever. Thus, the return was accompanied by disillusionments, one of the most traumatic of which was the sense of having no home.

Although the war in Europe ended de jure only in May 1945, many people, especially from Eastern Poland, began their journey home in the summer of 1944, while others waited for the Red Army to move deep into the West. [6] The example of Samuel Ponczak (1937–2022), a member of a Polish Jewish family from Warsaw, is telling. His family fled the German occupation in 1940, but the Soviet authorities sent it to Soviet Russia's Far East, to the Komi Republic. The Soviet government offered Soviet citizenship to the refugees in 1943, but the head of the family rejected the proposal. This step would have stymied his return to Poland, where the Ponczaks still had many relatives, about whose fate they knew nothing: "There were no newspapers that describe this thing. Obviously, we didn't know, and my parents didn't know what had happened to their family. That was the reason why the Russians did is they moved families like us to Ukraine because, at that time, Ukraine was already liberated. It was closer to Poland. So they just wanted to have all of the people as close to Poland as you could get. They eventually moved to Poland." [7]

So, the Soviet government moved the Ponczaks to Ukraine in 1944 in preparation for possible repatriation to Poland. Under these circumstances, the family lived for nearly two years in Kherson, which became their next home. This case is of particular interest to me as I have been working on the Holocaust in southern Ukraine in recent years. When interviewed, Samuel Ponczak shared his memories, revealing crucial details about daily life in the city immediately after the Holocaust:

Bill Benson: Once you were in the town of Kherson, you shared with me you were amazed that your father was driving a combine and farm equipment.

Sam Ponczak: Right. Right.

Bill Benson: What was he forced to do there?

Sam Ponczak: There was very little choice in labor. We were moved to Kherson, which was in Ukraine and warmer than Siberia. One of his first jobs was to drive, because he was a man. Men learn how to drive. Now I wonder how the man who had never driven anything mechanically or even a bike was driving the huge machine. But he did. I remember it. Eventually, we ended up closer to the town, Kherson, because that combine was from the town. The men were not far from the river. A couple of things about Kherson are as follows: one, my sister was born when we were in Kherson. I got myself sick with malaria when we were in Kherson. And in Kherson was the first time when I found out that I was a Jew. My father didn't go around telling me, Sam, you know you are a Jew. No. He was not a practicing, religious-practicing Jew. I found out not from him. As I walked to the farmers' market, there was a quadriplegic man with no legs. He was pushing himself on a board with some wheels. I'm sure some of you know what I'm talking about. He pulled up next to me and just cursed us out. I don't want to repeat it. How the heck you Jews survive — didn't Hitler finish you off? I was just taken [a]back. I understood it was Russian. Nobody needed to translate it to me. I had the talk with my father. He said, Sam, yeah, we are Jews. We are not very much liked around me [read: here]. That's a man who spit out his guts. That's how I found out I was a Jew. There was a similar incident where my father took me, and it was the fall of 1945. It was after the war. The war has ended already. I become aware of it.

"It was a different time. I walked into a room. I did not know where I was, but I saw a whole bunch of young men in military uniforms. They even had their arms next to them. They were sort of moving like that. I did not know what they were doing. They were chanting. What was very striking to me, I'll never forget it, they had tears in their eyes. I didn't expect it from young men, military men. They were the heroes for a boy like me. And I remember the episode. I did not sit down with my father and discuss it then. Because I had — I was a kid. I had other things on my mind. But many years later, very many years later, I remember I asked my father what was that episode? I described it for him just like I'm describing to you. So he tells me that was a makeshift synagogue. And the day we went, it was the day of Yom Kippur 1945. That was the day of atonement among the Jews. They prayed to God for forgiveness and all of that. I asked him why were the men crying? He said these were the Jewish boys from the Soviet army that had just returned from Poland or Germany. They were coming back home to Russia somewhere. They decided to celebrate Yom Kippur. That's what I saw. That was another event that sticks in my — excuse me — my mind." [9]

This interview demonstrates that Jewish life in the region had not disappeared once and for all after most of the local communities were killed by the Nazi occupation authorities in 1941–1942. Jews continued to live in Kherson thanks to these displaced people, who had found temporary or permanent shelter in the city but longed to return to or regain their homes.

The fourth day of the seminar was devoted to understanding the questions of dispossession, restitution, and reparations in other contexts of the Nazi regime's genocidal policy and genocide on the whole. We examined the experience of the Roma people, whose fate was at some points interwoven with that of the Jewish community. The Roma also devoted considerable efforts to obtaining compensation for their losses in the postwar period. In studying this question, we referred to a chapter from Ari Joskowicz's recently published monograph. [10]

During the second half of the day, we visited the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of the American Indian. The visit began with a discussion with David Penney, Associate Director of Museum Scholarship, who talked about the museum's mission and repatriation mandate. This was a unique occasion to learn more about Native American law, which is based on various sources, including the Constitution of the United States of America, treaties, federal and state laws, court judgments, administrative resolutions, and laws formulated, implemented, and approved by sovereign tribal governments. As of today, Native American law includes a broad spectrum of norms, from those regulating the environment and natural resources to criminal and civil jurisdictions, protection of sacred sites, and tribe recognition and membership. [11] This legislation emerged as a result of efforts to counter the discriminatory policy that was in place in the U.S. concerning the Native American peoples, which, in some cases, bore the hallmarks of genocide, researchers say.

So, we were talking about a comparative analysis of genocides. We should always remember the inadmissibility of a "hierarchy of suffering" or "competitive victimhood." Rather, the focus here is on identifying distinctive and similar features of genocides and (similar non-genocidal) actions and then singling out those that are repeated in most cases. In researching such comparative contexts, we inevitably confront the problems of home, property, their loss, and the process of returning.

On the fifth and last day, we summarized the results of our work and shared our thoughts on integrating the discussed problems into future teaching. We worked in small groups throughout the seminar to create student assignments using the suggested tools and resources. Our work yielded concrete decisions suitable for classroom teaching.

Reflections

During the seminar, I, the only representative from Ukraine, could not help thinking about the relevance of the topic of dispossession, restitution, displacement, the loss and restoration of home, and related issues in the context of Russian aggression against Ukraine. As of April 2022, 3.5 million Ukrainians lost their homes, or their homes were damaged. As of early 2024, there are 4.9 million internally displaced people in Ukraine, and the number of refugees abroad has reached 6.9 million people. These horrible statistics notwithstanding, it is essential not to lose sight of the connection with the real stories of people living through the same experience in its various manifestations and needing help and support. Psychological research can be of assistance here. As the psychologist Tetiana Franchuk notes, "We need to remember that we cannot change the situation in which we have found ourselves. We cannot change the fact that a war is going on and that people are losing their homes, apartments, and valuable things. What we have in our power is to change our view of this situation either independently, if we have sufficient inner resources, or with the help of a professional." The topic of working with trauma inflicted by displacement and the loss of home is addressed in a study by Professor Renos Papadopoulos. [12] One of his books, Involuntary Dislocation: Home Trauma Resilience and Adversity-Activated Development, was recently published in Ukraine.

Of course, the current context of the Russian Federation's war against Ukraine should not compete or be contrasted with the experience of Holocaust victims. The genocide committed by the Nazis has left a considerable number of questions for discussion, which are universal and relevant today. It is hardly surprising that Papadopoulos begins his book about the loss of home, resilience, and other related questions by referring to the dilemma he formulated under the impact of his participation in a special Holocaust victim commemoration event. It was attended by Zdenka Fantlová (1922–2022), a Holocaust survivor who became an example of Jewish resistance and human resilience. She said that she tried not to take on the role of victim, even though she found herself in extreme conditions. However, her speech at this event was considered somewhat "dangerous." Her absolute defiance and unshakable resilience could have the effect of masking and minimizing the horrific nature of the Holocaust and its destructive consequences. Papadopoulos writes that his unease resided in the fact that Fantlová's unbreakable spirit looked so convincing that it could have created a grotesquely false impression, as though the Holocaust did not necessarily have negative consequences: "Instead of becoming a broken person marked for life by visible and invisible wounds, there she was, standing upright and unbroken, full of vitality in her nineties, radiating calm resilience, and optimism, and with an unquenchable zest for life. She presented her life and struggle without any kinds of heroic pretensions or subtext; on the contrary, with human ordinariness and humility." [13].

Papadopoulos thus poses quite a few questions, such as: What should be the focus of attention of humanitarian aid workers or researchers working with victims of violence today? For him, the dilemma is that, when emphasizing people's achievement in survival and resilience, we risk minimizing the scale of their sufferings and thus cannot offer them the right support they might need. In the latter case, there is another "danger": we may unintentionally convey a message that downplays the severity of adversities and the extent of human rights violations experienced by victims of genocides, crimes against humanity, war crimes, etc. These are real dilemmas. They cannot be ignored, and the complexity is that we often do not even realize they exist. [14]

Endnotes

- Stan Lavinia and Nadya Nedelsky, Encyclopedia of Transitional Justice (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013).

- Shannon L. Fogg, "Home as a Site of Exclusion: The Nazi Occupation, Housing Shortages and the Holocaust in France," Journal of Modern European History 20, no. 2 (2022): 167–82, https://doi.org/10.1177/16118944221095134.

- Leora Auslander, "Holocaust Lists and Inventories: Recording Death vs. Traces of Lived Lives," Jewish Quarterly Review 111, no. 3 (Summer 2021): 347–55, https://doi.org/10.1353/jqr.2021.0030.

- Elizabeth Anthony, The Compromise of Return: Viennese Jews after the Holocaust (Detroit, Mich.: Wayne State University Press, 2021).

- Tim Cole, Holocaust Landscapes (London: Bloomsbury, 2016). See, in particular, the Introduction, "Holocaust Landscapes," pp. 1–7; the Prologue, "Returning Home/Leaving Home," pp. 9–20; and the Epilogue, "Returning Home/Leaving Home," pp. 215–24.

- Anna Cichopek-Gajraj, Beyond Violence: Jewish Survivors in Poland and Slovakia, 1944–48 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014). See, in particular, the Introduction, pp. 1–10, and Chapter 1, "Return to 'No Home,'" pp. 30–53.

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Collection. Interview with Sam Ponczak: 2019 April 11. RG Number: RG-50.999.0683.

- This reference to malaria may indeed be correct because there were outbreaks of this disease in southern Ukraine in the 1920s, or perhaps the narrator was talking about the flu or some other illness accompanied by a fever.

- USHMM, Interview with Sam Ponczak, RG-50.999.0683.

- Ari Joskowicz, Rain of Ash: Roma, Jews, and the Holocaust (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2023), pp. 136–66.

- Library of Congress, American Indian Law: A Beginner's Guide, https://guides.loc.gov/american-indian-law

- Renos K. Papadopoulos, Involuntary Dislocation: Home, Trauma, Resilience, and Adversity-Activated Development (London: Routledge, 2021).

- Ibid., pp. 9–10.

- Ibid., p. 11.

The photographs used in this publication are from the private archive of Yurii Kaparulin and open sources.

Yurii Kaparulin is an Associate Professor in the Department of National, International Law and Law Enforcement at Kherson State University and a Fellow at the Weiser Center for Europe and Eurasia (WCEE), University of Michigan. He obtained the Candidate of Historical Sciences degree in 2012 and an MA in Law in 2022. His research interests are the history of Eastern Europe in the 20th century, the study of the Holocaust and genocides, and human rights. His research has been published in various scholarly journals, including Holokost ta suchasnist′; The Ideology and Politics Journal; Colloquia Humanistica; City History, Culture, Society; Problemy istoriї Holokostu: ukraїns′kyi vymir; Eastern European Holocaust Studies; Ukraїna Moderna, as well as in various media outlets, including BBC News Ukraine. Kaparulin is at work on his book Between Soviet Modernization and the Holocaust: Jewish Agrarian Settlements in the South of Ukraine, 1924–1948. He has held postdoctoral fellowships at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (2018–2019), Yahad-In Unum (2019), New Europe College (2021), and Zentrum für Holocaust-Studien (2022). He was the director and co-screenwriter of the documentary films Kalinindorf and (Un)Known Holocaust in 2020–2021.

Yurii Kaparulin is an Associate Professor in the Department of National, International Law and Law Enforcement at Kherson State University and a Fellow at the Weiser Center for Europe and Eurasia (WCEE), University of Michigan. He obtained the Candidate of Historical Sciences degree in 2012 and an MA in Law in 2022. His research interests are the history of Eastern Europe in the 20th century, the study of the Holocaust and genocides, and human rights. His research has been published in various scholarly journals, including Holokost ta suchasnist′; The Ideology and Politics Journal; Colloquia Humanistica; City History, Culture, Society; Problemy istoriї Holokostu: ukraїns′kyi vymir; Eastern European Holocaust Studies; Ukraїna Moderna, as well as in various media outlets, including BBC News Ukraine. Kaparulin is at work on his book Between Soviet Modernization and the Holocaust: Jewish Agrarian Settlements in the South of Ukraine, 1924–1948. He has held postdoctoral fellowships at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (2018–2019), Yahad-In Unum (2019), New Europe College (2021), and Zentrum für Holocaust-Studien (2022). He was the director and co-screenwriter of the documentary films Kalinindorf and (Un)Known Holocaust in 2020–2021.

Originally appeared in Ukrainian @Ukraina Moderna

This article was published as part of a project supported by the Canadian non-profit charitable organization Ukrainian Jewish Encounter.

Translated from the Ukrainian by Marta D. Olynyk

NOTE: UJE does not necessarily endorse opinions expressed in articles and other materials published on its website and social media pages. Such materials are posted to promote discussion related to Ukrainian-Jewish interactions and relations. The website and social media pages will be places of information that reflect varied viewpoints.