Jewish Scouting: Born in Ukraine

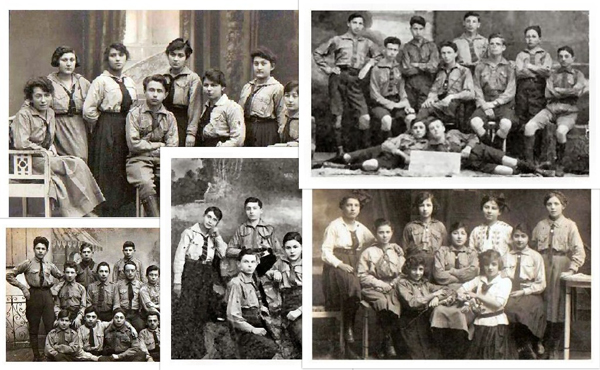

It is generally known that the city of Lviv is the birthplace of the Polish and Ukrainian scout movements: harcerstwo and Plast, respectively. However, to this day hardly anyone is aware that the capital of Galicia is also the birthplace of the world’s first branch of Jewish Scouting, known as Hashomer Hatzair.

“Young Guard” is the translation from the Hebrew of the name of the first Jewish Scout Movement, whose membership peaked in the period between the two world wars.

In the mid-1930s it had a membership of some 50,000 to 70,000. The “Guards” operated all over Europe, from Soviet Ukraine to France, from Estonia to Italy. Branches of the movement also existed in other countries, like China, the U.S., Tunisia, and Egypt.

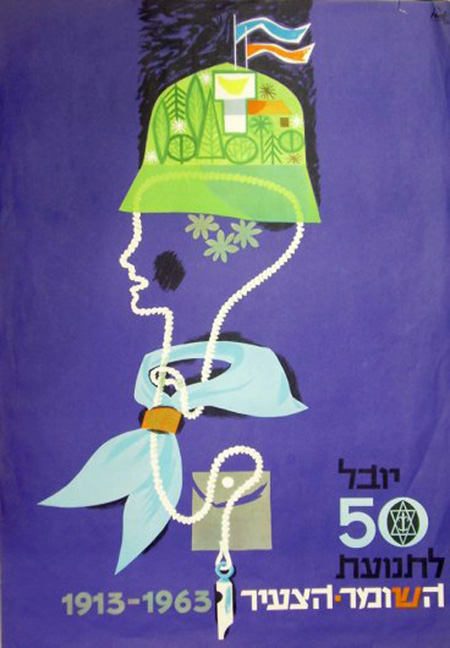

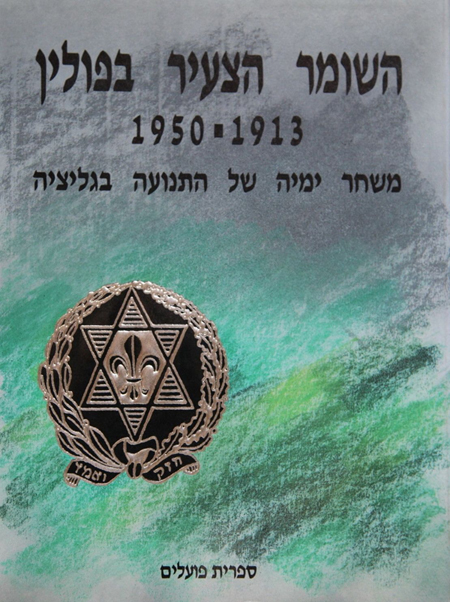

In 1911, when the first Plast [Ukrainian Scouts] groups were being formed in Lviv, the idea to create the first Jewish Scouting organization was born. In 1913 the Lviv organization chooses the name “Hashomer” (Guard), and that year is regarded as the date of the founding of Hashomer Hatzair. Various sources give different years and places of its founding. However, the organization itself claims that it was founded in 1913.

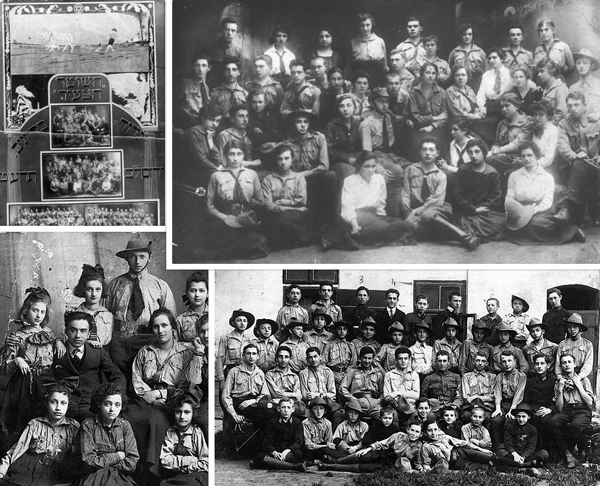

The organization developed dynamically, mainly encompassing Galicia, both the eastern (Ukrainian) and western (Polish) parts. By the outbreak of the First World War the “Young Guards” in Austria numbered 760 members in fifteen branches. In 1914 the organization became one of the first members of the Austrian Scouting Union (Pfadfinder).

In the summer of 1914, at the beginning of the First World War, the main organizers of the Guards left Lviv (which was soon occupied by [Russian] tsarist troops) and moved to Vienna, where the Main Shomer Council was founded in 1916. Why Shomer? Because both the Ukrainians and the Poles called the Guards “shomers” (from ha-shomer, meaning, guard).

In the capital of the Austro-Hungarian Empire the Lviv milieu of Hashomer Hatzair’s organizers published the world’s first Jewish Scouting manual, entitled Poradnik dla kierowników szomrowych (Vienna, 1917). During this period this Polish-language publication was the most accessible one to Galician Jews.

After Austrian rule was restored in Lviv, the Guards revived their activities. At its editorial offices located on Hrebinka Street (former address: 4/2 ul. Podlewskiego), the Jewish youth periodical Moriah popularized Scouting ideas. In August 1917 it issued a supplement, the world’s first Scouting magazine called Haszomer.

The Kholm, Volyn and Brest regions

In 1916 the German army occupied the Polish Kingdom, which was part of the Russian Empire prior to the war. As of 1918, local branches of Hashomer Hatzair had a membership of nearly four thousand young people.

The zone of occupation also included the Ukrainian regions of Kholm and Volhynia. These territories began to establish close contact with Galicia, and the Jewish Scouting Movement begins to spread there.

The Volhynian branches were founded by Mordekhai Gutgeld, who immigrated in 1920 to Palestine (where he joined the “Young Guards” movement) and eventually became one of the co-authors of Declaration of the Establishment of the State of Israel.

One of the founders of Jewish Scouting in these lands is believed to be the distinguished, innovative pedagogue Janusz Korczak (originally Henryk Goldszmit). Admittedly, his participation in the Scouting Movement requires further research.

The Polish researcher Leszek Gornicki is convinced that Korczak initially fought in the ranks of the Russian army. In 1917 he worked in children’s shelters near Kyiv and was physically incapable of performing the role that is attributed to him.

Jewish Scouting spread so significantly throughout Volhynia that as of 1923 (the same year that the first Volhynian branch of Plast was formed), Ukrainians were already sounding the alarm:

“In all cities and many towns in Volyn as well as in the Kholm region there are Polish and Jewish Scout groups; although not numerous, meaning, their membership is not large, nevertheless they exist.”

The history of the founding of the branch of Hashomer Hatzair, as described by Dusia Korin in his essay entitled “Hakhshara," is illustrative. Five gymnasium students who were returning from Kyiv to their native city of Dubno wanted to immigrate to Israel. Since there was no such opportunity, they founded a youth group.

At the beginning of 1921 two young men (Eliahu Makhrok and Binyamin Oz) visited Lutsk, where they met with J. Glikman, one of the first organizers of Hashomer Hatzair.

This meeting in Dubno led to the founding of a “Guards” branch. Since the city bordered on Volhynia and Galicia, ideas for developing the organization were drawn from both regions.

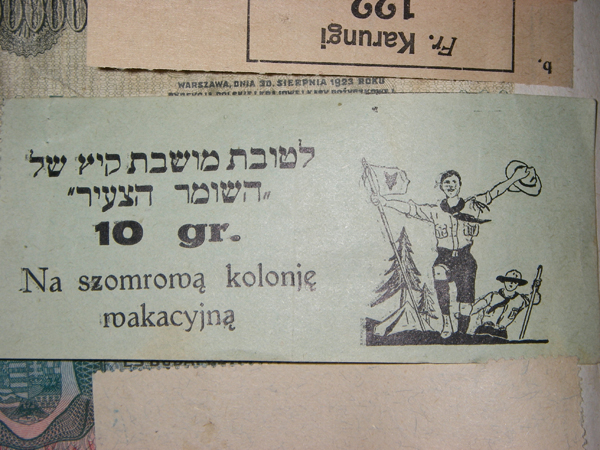

The branch organized summer camps, including together with other branches in the area. Camping took place mostly in the vicinity between Dubno and Kremianets.

The last camps date to 1938–1939 and even 1940 (after Volhynia was occupied by the USSR). True, this last camp was forced to change its location several times, in fear of repressions on the part of the Soviet authorities.

Summer camps/colonies were also organized by other Volhynian branches. The Rivne-based “Guards” organized their first camp in 1926 in the village of Novostav (today: Rivne raion), where a camp operated in the 1930s as well.

A system of seven training branches was organized in Volhynia, including in Malynsk and Rafalivka (today: Berezne raion and Volodymyrets raion, respectively, Rivne oblast), Kostopil, and Rivne.

Every “Guard” was on probation for at least one year. After this s/he swore the Scout oath, as a rule during the Lag BaOmer holiday. The sworn oath offered members the right to wear the Shomer pin. This pin has remained unchanged to the present day. It features a braided wreath of bay and oak leaves; at the bottom, on the ribbon, is the Guards’ slogan חזק ואמץ (Be strong and of good courage!).

During the period between the two world wars, Hashomer Hatzair’s center of development in Poland’s Wolyn Voivodeship was the city of Rivne. This branch was founded after the Polish occupation of 1920, and it was under the personal guardianship of the movement’s leaders based in Warsaw. The Volhynia region was home to 68 branches of “Young Guards.”

Branches of Hashomer Hatzair actively developed in the predominantly Ukrainian-speaking area of Berestia (during the interwar period it was the Polissian Voivodeship of Poland). In 1918–1919 the western part of this region was part of Kholm Gubernia of the Ukrainian National Republic, so the possibility cannot be excluded that this work took place during Ukrainian rule. The “Young Guards” operated in Brest, Кobryn, and Davyd-Horodok (today: Stolin raion, Belarus).

The UNR and Soviet-ruled Ukraine

The 1917 Revolution in tsarist Russia brought freedom of activity, including to young Jews. In Russian-ruled Ukraine, their organizations began to appear and develop en masse: from Maccabi sports clubs to the Zionist movement of Tse'irey Tsion (Union of Young Workers and Young Zionists). Scout branches soon appeared, which soon formed the nucleus of Scout branches.

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk in March 1918 led to the disappearance of borders between Galicia, Volhynia, and Dnipro Ukraine. Ukrainian statehood contributed to the development of the Jewish Scout Movement.

Thus, on 1 April 1918 a Jewish Scout legion was founded at the Maccabi center in the city of Kremenchuk, eventually becoming the most powerful branch of Hashomer Hatzair in Soviet Ukraine.

As of 1922, the Kremenchuk-based legion (the Maccabi’s legions were called gubernial associations) had 850 members divided into three age groups.

They were organized into appropriate divisions: а) two detachments of “Shomers” (Guards), up to 15 years of age; b) five detachments of “Scouts”; and c) five branches of “zevonim” (“wolf cubs”), for children aged 8–11. The “Scouts” division also included the 6th detachment in Kriukiv, which is now a bedroom community of Kremenchuk.

In Poltava, a local legion of Jewish Scouts was founded in 1919. It had nearly 200 members grouped in a detachment of Scouts and a pack of “wolf cubs.” The Scout detachment included three divisions (called kurins in Plast), with four groups in each.

Each division had two groups of Scouts and Girl Guides. In August 1925 some 200–205 people attended a secret meeting of the Poltava legion of Hashomer Hatzair.

In 1920–1922 there were three Jewish Scout groups in Odesa. One of them was attached to the Maccabi Sports Club. Rebeka Dub, who was a member, recalls:

“The task of this movement was the moral education of children built on universal values. These values were the ‘scout’s commandments’... During marches we were taught to navigate by compass, to distinguish between various types of grass, to signal with flags, and other Ranger skills. Tribunals for the children’s misdeeds were not held, but they were taught to be compassionate, to love, to be friends.”

In the early 1920s the members of Maccabi were mostly young people, and it followed Scouting methods. The very first branches often bore the purely British term “patrols.”

Besides Kremenchuk (the largest branch) and Odesa, there were branches in Sumy, Zhytomyr, and Kharkiv; the latter branch had over 400 members. It was believed that “there was not a single city or town without a Maccabi organization, and the movement’s total membership was estimated at 4,000.

In view of this active work, on 4 August 1922 the Central Committee of Ukraine’s Komsomol organization held a special meeting, after which the CC CP(B)U circulated a letter “About the Struggle against Maccabi” to all gubernias. Plans were put in place to inspect all private sports clubs and, where necessary, to enlist Chekists [the secret police—Ed.].

Rebeka Dub recalls how one summer day in 1922 the Soviet authorities disbanded her Scout group:

"Young guys carried out our equipment and the banner from our room. One of the guys said: ‘Whoever wants to go to the ‘Yuki (Young Communists), sign up; we will decide whom to take; whoever does not want to—go home.’” After emptying the room, the guys closed it, and we dispersed.”

The concealment of legal Scouting activities within the Maccabi framework led Jewish Scouts in Soviet Ukraine to switch to semi-legal and illegal status.

Yosyf Kendel in his history of the Jews in the Soviet Union states that Hashomer Hatzair was founded at a secret congress in Moscow in 1922, after which the organization launched wide-ranging activities, including a clandestine press.

A year later, on 9 October 1923, the CC CP(B)U [Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine] was forced once again to order gubernial party committees to liquidate the Jewish Scout Movement. The struggle included mass arrests; 72 organizers of the Kremenchuk branch were arrested.

Although the Soviet government’s actions sparked a public outcry that included anti-Soviet appeals, Scouting activities gradually faded away. The local headquarters moved from Kremenchuk to Kharkiv, the then capital of the Ukrainian SSR.

In August 1925 Karl Karlson, the head of the GPU of the Ukrainian SSR, sent a memorandum to Lazar Kaganovich, Secretary of the CC CP(B)U, in which he reported that the dynamics of Hashomer Hatzair’s development in Ukraine, both the left- and right-wing orientations, made it impossible for the Soviet authorities to draw up a correct tally of their members.

In certain locales half of all Jewish children were members, and the struggle against them was impossible because these were mostly children between the ages of 13 and 16, while “little Herzlites” and “Tsofim” were 10 to 11 years of age. Arrested leaders were immediately replaced by new ones

It came as a shock to the Chekists that on 28 May 1925, the fourth anniversary of the founding of the local Hashomer Hatzair legion, Jewish Scouts set up night relays and mobilized nearly 400 members to attend their festive meeting in Pushcha Vodytsia, a neighborhood of Kyiv.

This audacity led to a sharp rise in repressions. Over the next two years 55 branches operating in Soviet Ukraine were forced to move underground; in the late 1920s–early 1930s they ceased to exist.

Plast and the “Young Guards” in Interwar Galicia

After the First World War and the Ukrainian–Polish War ended, Hashomer Hatzair on the territory of Poland began operating simultaneously in two centers; one of them was based traditionally in Lviv, and the other in the capital city, Warsaw.

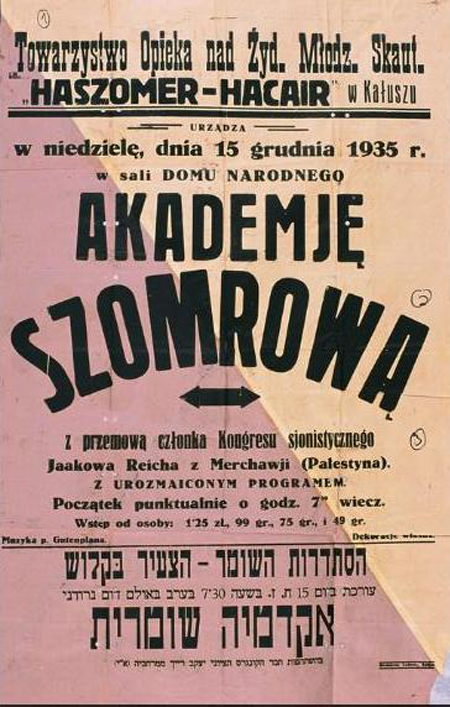

In 1920 one of the key congresses of Hashomer Hatzair took place in Lviv, where the idea arose to carry out group training of Scouts for life in the Promised Land. Shortly afterwards shomer colonies were organized to teach skills adapted to life in the settlements of Palestine.

Lviv was the only large city in interwar Poland where “Young Guards” held monopoly status in the city’s Jewish Scouting Movement. In other cities the shomers’ initial leadership was forfeited, as they were pushed out by other Jewish Scout movements.

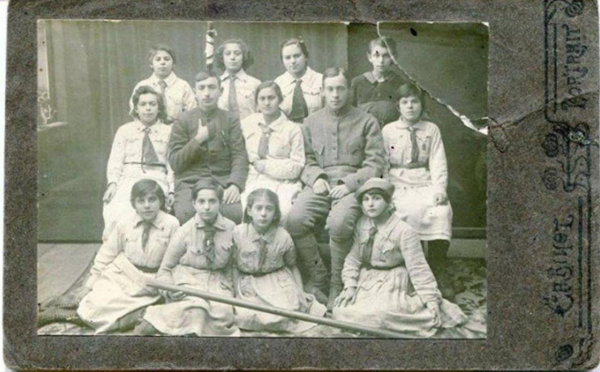

Branches of “Young Guards” in the Ukrainian part of Galicia numbered in the dozens. In the city of Stryi in the 1920s Jewish Scouts from Hashomer Hatzair grew up alongside the young Plast member Stepan Bandera. While Plast members dressed in khaki uniforms, the shomer uniform consisted of a gray shirt and blue shorts.

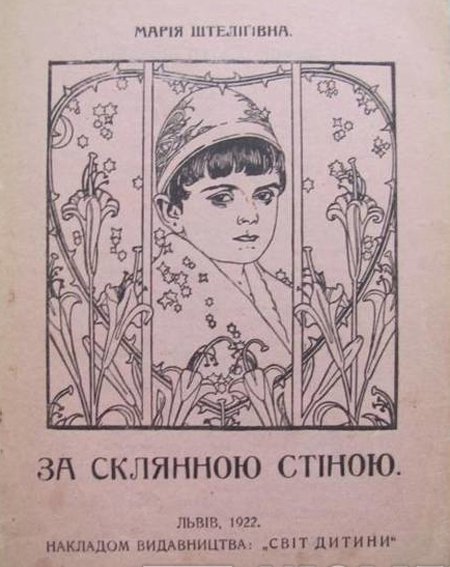

When Stepan Bandera was getting ready to join Plast, Jewish Scouts had already entered Ukrainian Galician literature. The Svit dytyny Publishers issued a short story by Maria Shtelika called “Behind the Glass Wall” (Lviv, 1922). Ukrainian Plast officials wrote:

“A charming story about the life of Jewish Scouts/Shomers. Reading it will awaken an understanding of and admiration for the ideas of Plast in the souls of our young people.”

Relations between Plast members and Jews were friendly. “Among us were Jewish children with whom we were friends.” Stepan Haiduchok, one of the cofounders of Plast, was married to a Jewish woman.

It was normal for a Plast member in Kosiv to be awarded the highest medal, the Plast Merit Cross, “for saving a Jewish woman from drowning.” A Jewish woman could be assigned as a guardian of a girls’ Plast group in the above-mentioned city of Stryi.

Jewish Scouts took part in Plast events. For example, on 29–30 June 1929 a district Plast gathering took place in Ternopil, which was attended by Plast otaman Severyn Levytsky. The following evening a festive Plast concert took place in a jam-packed hall. “Among the guests was a group of Jewish Girl Guides, who were very glad to have found out about this.”

Plast members and Jewish Scouts competed against each other at sports tournaments. On 27 May 1922 a soccer match took place in Sokal between the Shomers and P.S.K. (Plast Sports Group of the ІХ Plast Regiment).

The game ended in a tie, 2:2. In October of that year, when P.S.K. was competing against the Maccabi Sports Club, the Plast team won with a score of 4:0.

The Supreme Plast Council subscribed to the publications of Hashomer Hatzair. One of them was the periodical Haszomer, the same one that had begun coming out in Lviv back in 1917. У 1922–1923 Plast subscribed to the Warsaw-based periodical for older shomers called EL AL (from the Hebrew “To the skies,” now the name of Israel’s largest airline company). The brother of the Plast founder gave the following assessment of this publication:

“This ‘ephemera,’ put together half in Polish and half in the Jewish (Hebrew) language has interesting content that follows a philosophical-polemical direction… Our older Plast youths should acquaint themselves with the ideas put forward in this periodical; meanwhile, perhaps, they might find the impulse to teambuilding and the continuation of Plast’s work, as this happens in other [organizations]…”

Hashomer Hatzair and Plast faced an identical challege. The World Scout Bureau refused to allow these organizations to join because they were organizations of stateless peoples. Participation in world Scouting events was possible only through membership in a national Scout organization of a given country.

Throughout the 1920s Plast and the “Young Guards,” who sometimes interacted with each other, categorically refused to join the Union of Polish Scouts because membership was contingent on loyalty to the Polish state.

In other words, it was necessary to swear an oath of loyalty to Poland. In 1930 the Poles banned Plast, and despite the Poles’ more indulgent attitude toward the “Guards,” the Jewish organization was not able to join the international Scout Movement.

Shomers and Plast members often crossed paths on their travels and in camps, even in the 1930s, when Plast was already banned. “I remember how we would go to a Plast gathering, and run into Jewish shomers,” Uliana Sitnytska recalled later.

“…In 1932 we, senior Plast Scouts, organized a camp in the Hutsul region, in the village of Prokurava, on a large piece of land near a river. Here we had a meeting with a Jewish organization similar to Plast. They called themselves ‘shomers.’ They were camped opposite us. It was a mixed camp of boys and girls.”

Bukovyna and Transcarpathia

The Jewish Scout Movement in Bukovyna was established in 1918, during the First World War (Plast, the Ukrainian Scout Movement, had been founded in Chernivtsi four years earlier).

The Scout idea was brought by refugees returning from their temporary stay in Vienna. At first the organization was called Histadur but eventually it was transformed into a local branch of Hashomer Hatzair.

Having lived through the brief period of Ukrainian statehood in November 1918 and ending up under Romanian rule, the local shomers preserved their Viennese roots. The main working language of Jewish Scouts in Bukovyna was German, as was the base literature.

Besides Chernivtsi, the main branches were in Storozhynets and the Suceava area (Suceava, Siret, and Rădăuţi [Ukr. Radivtsi]. In 1923 the Jewish Scouts of Bessarabia (today: Moldova) recognized Chernivtsi as their leading center. Shomers from other territories of prewar Romania eventually followed suit.

In 1924, when the world network of Hashomer Hatzair arose in Gdansk, Chernivtsi was recognized as the third most important center for the development of this movement, after Lviv and Warsaw.

Life under Romania evolved in different ways. There was cooperation with the Romanian Scout Movement (Cercetaşii) and persecution at the hands of the Siguranța, the Romanian secret service. As strange as it may be, in the late 1930s the activities of the “Young Guards” in Romania intensified, owing to the fact that they succeeded in obtaining official registration as the organization Skautnbundes der Shomrim.

Another branch of the Jewish Scout movement—this one Hungarian-speaking—operated in Transcarpathia. It arose in 1913 in Budapest, under the name Kadimah, meaning, “Forward.” A branch of this movement was founded in 1920 in Transcarpathia, the first Scouting organization in the region. It is interesting that similar branches in Košice and Bratislava [Slovakia] appeared only in 1921.

The creator and permanent leader of the Transcarpathian Kadimah, which joined the “Guards” movement in the mid-1920s, was an engineer named Propper. During the World Scout Jamboree in Hungary in 1933 he was the deputy of Yulian Revai, the head of the Ukrainian delegation, whose members included a group of Transcarpathian Jews.

On 29 April 1934, when Propper tragically drowned in the Borzhava River near Berehove, Plast leaders wrote that he had “contributed much to organizing Plast in Transcarpathia.”

It is interesting that Jews also joined Plast, the Ukrainian Scout organization. For example, out of sixtreen members of the Oleksa Dovbush branch of Plast, four were Jews.

This branch worked without adult guidance, owned a boat and a library containing 46 books, and published the now-legendary typewritten magazine The Sevliush Plast Scout. As of October 1925, Plast in Transcarpathia had 538 members, including 27 Jews (5 percent of the total membership).

In 1925 Jewish Scouting in Transcarpathia was the second largest after the Ukrainian Scouts. Branches of Kadimah had a total membership of 396 people, followed by Czech branches numbering 102 members. The Hungarians had only 2 branches with 63 members (another 42 Hungarians were members of the Ukrainian Plast organization).

It should be noted that half or more than half of all Jewish Scouts in Czechoslovakia were concentrated in Transcarpathia.

In 1932 there 10 Jewish Scouting branches numbering 565 members. As of 1930, there were 30 branches of Hashomer throughout the region, with a total membership of only 700 people.

By 1934 there were 26 branches of Jewish Scouts in Transcarpathia, with 710 members. For the purposes of comparison, the local Plast organization had 88 detachments and 3,280 members.

Every year Ukrainian and Jewish Scouts in Transcarpathia camped either together or side by side. The first joint camp was held in 1924 in Kamianytsia, near Uzhhorod. The commandant of the Ukrainian section was Leonid Bachynskyi, and on the Jewish side it was Béla Seren (there was also a commandant for the Hungarians).

Among the 109 participants of the Ukrainian camp, which took place in 1926 in Luhy, near Svaliava, were 8 Jews. A participant of the Plast camps that took place in Luhy in 1934–1938, recalls:

“Down from our Ukrainian camp was the camp for Hungarians—Cserkész, and even lower down was the Jewish one, Khadimah [Kadimah]. Our neighbors came to us, and we went on visits to them for ‘camp bonfires,’ and all three camps competed in demonstration programs. True, they set up ‘camp bonfires’ rarely.”

There were various pages in the history of Ukrainian–Jewish relations, particularly Scouting ones… Roman Shukhevych, a member of Plast in Galicia, was able to pass himself off as a Jew and gain an audience with the rabbi of Transcarpathia.

During a reconnaissance mission to the village of Velyka Kopania, Emerykh Yuda, a Jew from Rakhiv who was a Plast Scout, lost his life fighting for Ukraine’s independence. Another Jew who lost his life for Ukraine’s freedom was Mykola Vainberger, a Jewish teacher from Malyi Berezny, who was one of the organizers of the Carpathian Sich and possibly one of the co-founders of the Jewish Scouting Movement. More research must be done on our history.

Yurii Yuzych

28.12.2018

Istorychna Pravda’s ‘Shalom!’ media project, which explores the Ukrainian-Jewish dialogue, is made possible by the Canadian non-profit organization Ukrainian Jewish Encounter.

Translated from the Ukrainian by Marta D. Olynyk.

Edited by Peter Bejger.