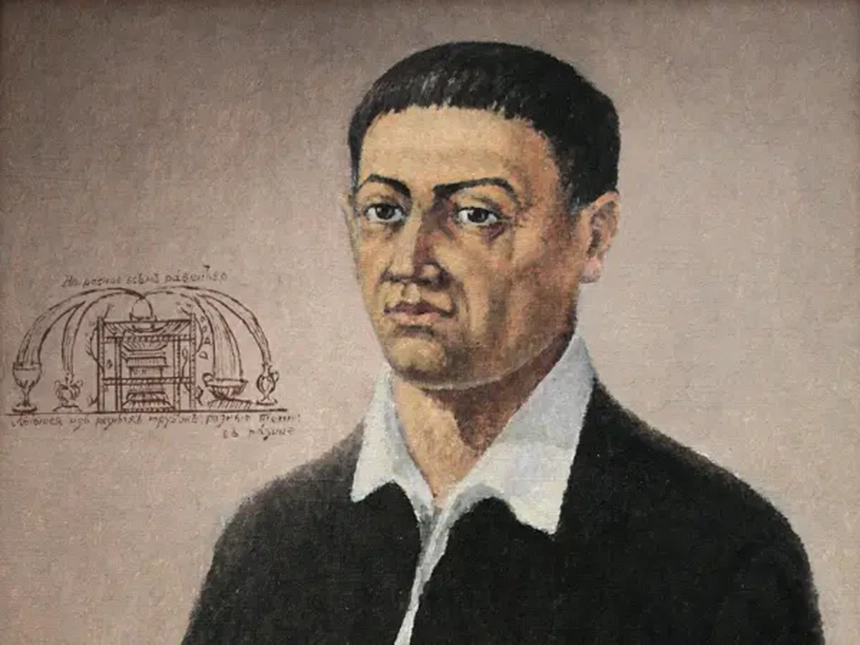

Jews in the life and literary works of Hryhorii Skovoroda

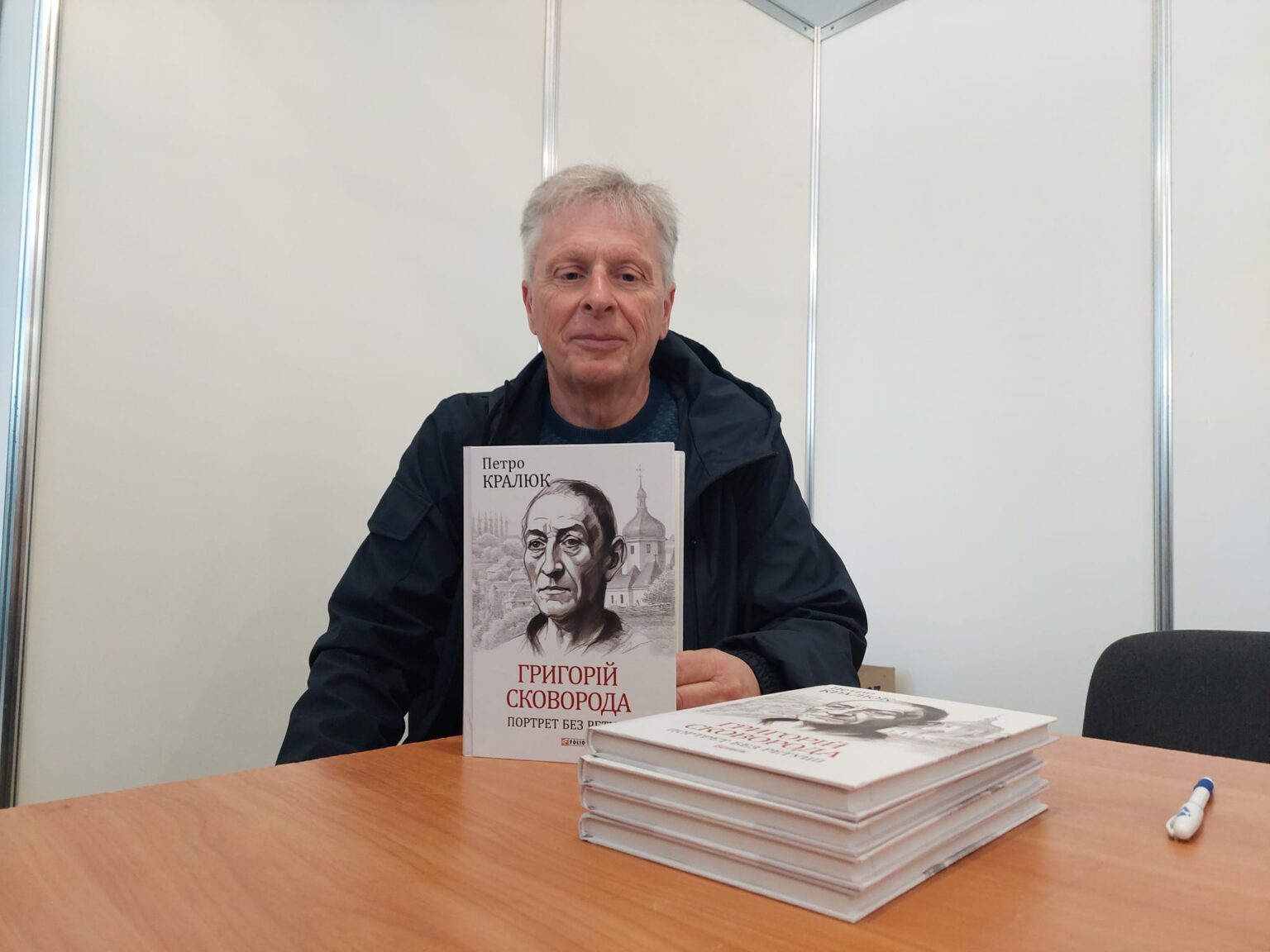

Professor Petro Kraliuk of the Ostroh Academy discusses Hryhorii Skovoroda's connections with Jews and Jewish culture.

Skovoroda and Jewry

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: Today, our guest in the studio is Professor Petro Kraliuk, сhairman of the Academic Council at the Ostroh Academy. We will talk about the role of Jews and Jewish culture in the life of Hryhorii Skovoroda. How many sources and information do we have about this?

Petro Kraliuk: Let's start from the fact that Skovoroda signed some of his later works as Var-Sava, i.d., the son of Sava. This is a purely Jewish form. And this is not at all accidental. He was interested in Jewish culture and the Old Testament. There were many Jews who converted to Christianity in his circle. In one way or another, they preserved some Jewish traditions. So, it is not surprising that these kinds of Jewish elements exist in Skovoroda's works.

However, these elements were ignored, both in Soviet times and in our days. Clearly, some stereotypes are at work here. There is an image of Skovoroda as a truly Ukrainian philosopher close to the Ukrainian peasantry, mixed with ordinary people, etc., although this was far from clear. So, how could there be anything Jewish there? And yet, he communicated with, as I've mentioned, Jews who had converted to Christianity and people interested in Jewish culture. One such figure was Simon Todorsky, one of Skovoroda's principal teachers who taught him classical languages, including Ancient Hebrew.

As far as we can judge, Skovoroda knew Ancient Hebrew. His level of competence in Hebrew is unclear, but he was most likely able to read ancient Hebrew texts. There is even a record that he allegedly walked around with a Hebrew Bible. It might be a legend, but there is no doubt that he could read Hebrew texts.

Influential figures in Skovoroda's life

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: Who else had an impact on Skovoroda and his worldview?

Petro Kraliuk: Let's talk about Todorsky first. This was certainly an interesting figure. He received a Western education after studying for a long time in Western Europe, particularly in Germany. Todorsky was one of the leading teachers at the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy and studied Ancient Hebrew and other languages there.

I'm aware that this will not sound very positive now, but he was one of the main teachers of Catherine II. When she came to Russia, she needed teachers of the Russian language and had to familiarize herself with Orthodox traditions, etc. And that's when Todorsky stepped in as her main instructor.

The same person was one of the principal teachers of both Skovoroda and Catherine II. In the current context, this does not come across as something positive, but that's how it was.

Skovoroda studied at the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy, where he was influenced also by others. Some highly qualified teachers worked there, including Hryhorii (Heorhii) Konysky, one of the leading philosophers and theologians at the academy. Many of his interesting works have been preserved, particularly works of fiction.

There was also Paisii Velychkovsky. I don't know to what extent he could influence Skovoroda, but curiously, he was born the same year (1722) and died the same year (1794) as Skovoroda. Velychkovsky belonged to a priestly family and is known primarily as an Orthodox mystic. He is recognized as a saint in Ukraine but is even more venerated abroad. Velychkovsky is one of the leading figures and highly respected saints of the Romanian Orthodox Church. He lived in what is now Romania for a long time and founded a number of monasteries.

Velychkovsky also wrote multiple works in the Hesychast vein. He and Skovoroda essentially belonged to this movement, Hesychasm. When I'm asked about its essence, my answer is very brief: "The world tried to catch me but failed." This famous phrase was allegedly written on Skovoroda's grave, according to his will. Hesychasts believed that one had to escape from the world and isolate oneself. There was a great Hesychast tradition in Ukraine, which included Ivan Vyshensky, Vitalii Dubensky, and others. These people believed it was necessary to leave the worldly bustle behind and seek a kind of religious, spiritual seclusion.

We see something similar in Skovoroda's life, even though he refused to join a monastery. He believed that a kind of spiritual salvation had to be sought outside the monastery.

Skovoroda and Jewish converts to Christianity

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: One very peculiar figure in Skovoroda's milieu is Neiman Petrovych, a resident of the Babai village. What do we know about him?

Petro Kraliuk: Information is scant, but we do know Skovoroda communicated with this man. He was a Jewish convert to Christianity, one of many in Ukraine. We sometimes have this idea that Jews did not mix with Ukrainians in the 17th or 18th centuries, but this is not so. At least some of them accepted Christianity, including Petrovych.

There were even Cossack starshyna (officer) families with Jewish backgrounds, such as the well-known Kryzhanivsky and Markovych families. These were Jews who were baptized into Christianity. Later, they mixed with Ukrainian families, but the Jewish line was still there.

The same can be said about Neiman Petrovych. He left Judaism and accepted Christianity. Clearly, Jews were extremely negative about such conversions. They even believed that if a person converted to Christianity, he or she thereby renounced the family, religious or religious-ethnic affiliation, etc. However, Skovoroda communicated with such people and appreciated them. They usually knew Ancient Hebrew and read the Hebrew Bible, as did Skovoroda.

Skovoroda highly valued the Bible and believed that there were three worlds. According to him, one big world is the one we perceive with our senses. Then, there is the human world, i.e., the microcosm. The third world is the symbolic world of the Bible, which is best perceived in the authentic version presented to us, i.e., in Ancient Hebrew.

At that time, an educated person was supposed to know three sacred languages: Ancient Greek (the language of the New Testament), Latin, and Ancient Hebrew. Skovoroda knew all of them one way or another. The only open question is his level of competence. He could read texts in these languages. His knowledge of Latin was very good as he was able to communicate in it. Of course, he also knew Greek and Ancient Hebrew to some extent.

Attitudes to converts

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: I'd like to discuss the term vykhrest (convert to Christianity). It was used negatively in my family, which is terrible. How were such people perceived in Skovoroda's time? Did they have a choice, or were they forced to convert to have a life in this territory?

Petro Kraliuk: It had its pros and cons. Many other families like yours used this term negatively. Even now, I have more than once seen a negative reaction to a person changing their religious affiliation, such as an Orthodox Christian converting to Catholicism. Such conversions are quite common now because some Ukrainians have ended up emigrating, particularly to Poland. And it's better to be Catholic there to obtain certain preferences. So, some convert to Catholicism. I personally know such cases, and this is no surprise to me.

How do we view this phenomenon? You can take a negative attitude and say that abandoning one's faith is an act of betrayal. On the other hand, if a person feels comfortable accepting their new creed and does it sincerely, then why not? But there are, of course, many nuances here.

The same goes for the 17th and 18th centuries. As far as I can judge, religious conversions were common in Ukraine. We should not think of Ukrainian society as being entirely Orthodox. For example, when discussing Skovoroda, we fail to mention his mother, Pelageia Shanhyrei. Her last name is revealing. There was an aristocratic Crimean Tatar family of Shahin-Gireys who moved to the territory of Ukraine, adopted Orthodoxy, etc. How were they perceived? Some said they had betrayed their Muslim faith, but they believed becoming Orthodox Christians was the right thing for them to do.

As far as Jewish converts are concerned, Jews were persecuted during Bohdan Khmelnytsky's uprising, for example. Some researchers often emphasize this point, implying that it was almost a Holocaust, etc. This is not entirely true because, during the Khmelnytsky period, the Cossacks not only killed Jews but also forced them to convert to Christianity. And many Jews did.

Things of this nature continued in later periods, i.e., Jews converted from Judaism to Orthodoxy. Clearly, the Jewish traditions in which they were brought up manifested themselves one way or another, even after conversion. This was true about the people with whom Skovoroda was friends. One more figure that can be mentioned here is Volodymyr Kaligraf (Kryzhanivsky). He kept Skovoroda company during the latter's sojourn in Moscow.

Jews had, of course, a negative attitude to converts. They considered them traitors to their faith. To them, converts were dead people. They did not even consider them Jews. In contrast, Orthodox Christians viewed this in a generally positive light, as Jewish conversions supposedly showed that Orthodoxy was a stronger faith than Judaism. But then, some people, of course, were somewhat skeptical. So, the attitudes were ambiguous.

Sources on Skovoroda's links to Jews and Jewish culture

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: Are there any researchers or literature on Skovoroda's links to Jews and Jewish culture that you could recommend?

Petro Kraliuk: Honestly, I don't know of such studies. Much has been written about Skovoroda but not his attitude to Jewish culture. There were, of course, researchers, including those of Jewish origin, who studied Skovoroda, such as Isai Tabachnykov in Soviet times. He was a Jew, taught at Kyiv University, and defended his thesis on Skovoroda's oeuvre. He even found some previously unknown works by Skovoroda. Tabachnykov wrote a monograph, which was published in Moscow in the 1960s. It appeared in the "Thinkers of the Past" series, quite famous at that time. I did not find his monograph about the Jewish aspects in Skovoroda's works. In principle, this is understandable. It was written from the Soviet point of view, and there is a lot there that can be rejected, even though the volume included some interesting moments.

Nevertheless, I do not know of any research on Skovoroda and Jews. The Ukrainian and foreign literature on Skovoroda that I've read is silent on this topic, even though there are sources from which information can be drawn. In addition to calling himself Var-Sava in the Jewish manner, Skovoroda wrote letters that exhibited his interest in Jewish culture.

The Ukrainian-Jewish connection

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: It is very unfortunate that there are no popular works on Skovoroda's link to Jewry. Ukrainians and Jews have always lived not next to each other but together. And their cultures diffused into each other. This is an exciting topic for research.

Petro Kraliuk: Ukrainian society was not completely isolated in the 18th century when Skovoroda lived, and in the following and previous centuries. It was open to various influences.

Jews have lived on the territory of Ukraine since time immemorial, whether someone likes it or not. For example, there was a Jewish quarter even in ancient Kyiv during the rule of Prince Yaroslav. It was, in fact, not a quarter but a part of the city. There was even the Jewish Gate in Kyiv. The oldest extant written work from Kyiv is the so-called "Kyivan letter," written in Ancient Hebrew and kept in the Cairo Geniza. This letter mentions not only purely Jewish names but also Slavic ones. This suggests that some people of Slavic origin might have accepted Judaism or, conversely, Jews might have adopted Slavic names. So, this kind of diffusion continued for many centuries.

Let's take another example. The religious movement of Judaizers that emerged in the 15th century had its roots in Kyiv. These people took an interest in the Old Testament and some Hebrew texts and translated them into Ruthenian, or Ukrainian, we might say. You can find many more such instances. They have been mentioned here and there, but not that much in general, I think. And we often leave these things out, even though they were there.

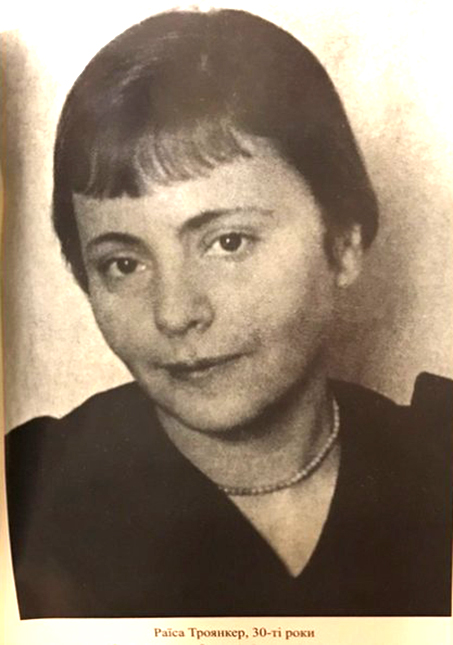

I can even draw parallels with modern times. Many people have watched the film Slovo Building and started talking about Raisa Troyanker, a Jewish woman who became a Ukrainian writer, even though she later started writing in Russian. She was born in a Jewish environment, a Jewish shtetl. When she broke up with her family and her Jewishness, it was poorly received by her next of kin. Troyanker became involved with Ukrainian culture. I'm not saying she was some luminary, but she was a person who, for some reason, became active in Ukrainian culture rather than Russian culture, which dominated at the time.

The renowned Ukrainian poet Moisei Fishbein is another great example. He was a Jew by origin but a Ukrainian poet and writer. He really did a lot for Ukrainian-Jewish understanding.

This program is created with the support of Ukrainian Jewish Encounter (UJE), a Canadian charitable non-profit organization.

Originally appeared in Ukrainian (Hromadske Radio podcast) here.

This transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

Translated from the Ukrainian by Vasyl Starko.