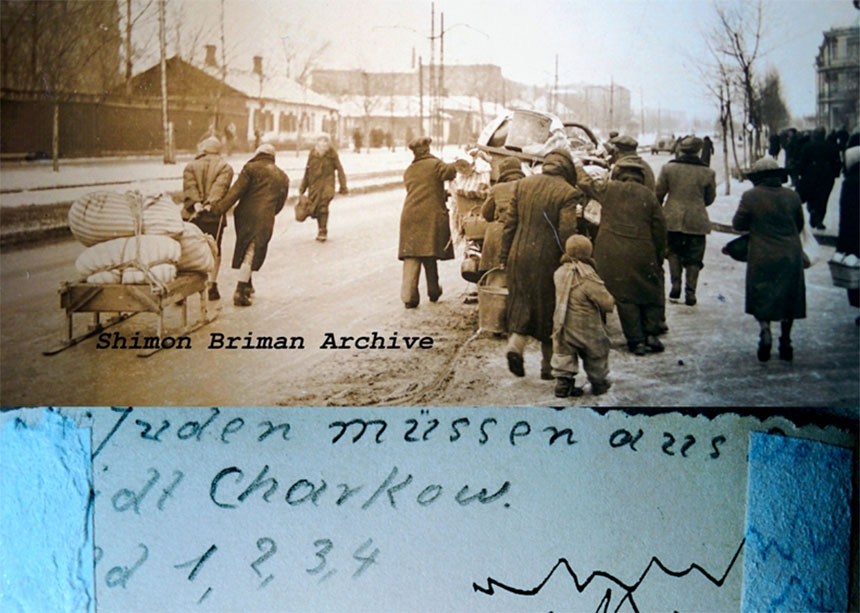

"Jews must leave the city of Kharkiv"

"Jews must leave the city of Kharkiv," wrote a German soldier or officer on the back of this photo, and calmly proceeded to write with his ink pen.

This photo can be dated even though it bears no date, which is rare. On 14 December 1941, the German commandant of occupied Kharkiv, Wehrmacht General Alfred von Puttkamer, issued an order to evict all of Kharkiv's Jews to the dilapidated barracks of the machine tool and tractor plants. For two days, 15 and 16 December, a stream of Jews slowly rolled along icy streets from the center to the outskirts for almost 20 kilometers.

The handwritten numbers 1, 2, 3, and 4 are very indicative. This German took four pictures out in the street, thinking he was photographing Jews on the move. But he was wrong: Three shots showed Jews with their simple belongings, while the fourth captured a peasant's cart. The man behind the camera just did not know how to distinguish Jews from non-Jews on the Eastern Front.

This is another proof that the Nazis would not have been able even to identify their victims without the help of local collaborators. Under Hitler's occupation, the Kharkiv City Council and its employees served the genocide of Jews to the fullest measure and for profit. I saw detailed correspondence in the archive about how thousands of apartments that "suddenly became vacant" after the extermination of the Jews were distributed among the city council employees.

As I look at this photo of people wandering in the cold toward their deaths, I think about the information gap. The Jews of Kyiv were killed on 29–30 September, while Kharkiv was surrendered to the Nazis on 24 October 1941. There was enough time to inform the Jews of the impending nightmare and the terrible danger of total annihilation.

There was also the entire month of November, when the Soviet command in Moscow already had accurate intelligence and underground data about the massacres in Babyn Yar and other locations. But no one was warned, informed by the radio, or in any other way.

Soviet intelligence had more important things to do than saving civilians from death: on 14 November 1941, a house in Kharkiv was blown up by a radio signal transmitted from Voronezh, killing General Georg Braun, commander of the Wehrmacht's 68th Infantry Division.

By June 1941, the number of Jews in Kharkiv peaked, reaching nearly 150,000 in a city of almost a million. This was followed by mass mobilization into the Red Army and mass evacuation of factories to the rear. The Kharkiv Jews were "fortunate" — if this word is at all applicable here — that almost 90% of them had gone to fight at the front or managed to leave for the East.

Under the Nazi occupation, 10,271 Jews were registered in the city. On 17 December, the relocation to the temporary ghetto barracks was completed, and the Jews were taken in groups to be shot in Drobytsky Yar from 17 December 1941 to 17 January 1942. The murders were carried out by the same Einsatzkommando S that had previously killed the Jews of Kyiv. It was supported by the units of the Sixth Army, which would later be destroyed at Stalingrad.

We will never know the exact number of Jews killed in Kharkiv. After Kharkiv was liberated, the Soviet experts involved in the exhumation measured the length and width of two ditches. Then, they multiplied these figures by the average density of corpses per square meter. That is why the victim count for Drobytsky Yar ranges from 12,000 to 15,000 or even 20,000 in various sources.

Several decades later, Soviet documents were deposed in the archive, describing the extermination of Kharkiv's Jewish population. In them, local officials crossed out the word "Jews," replacing it with the humiliating designation "residents of the central streets." Eighty years after the executions of Kharkiv's Jews by the Nazis, the graves of Holocaust victims were disturbed by the missile and artillery cannonade of the Russian occupiers. In February-March 2022, shells fired by Putin's army seriously damaged the Menorah, a monument to the Jews who died in Drobytsky Yar.

Looking at these photos, I think that it would probably be even more painful to see the faces of these people who are going to meet their deaths but are not yet aware of it.

Once, when still a child, I rode a tram with my grandmother Yulia in Kharkiv and asked her with childish naivety: "Were you also in Kharkiv during the war?" My grandmother looked at me sadly and quickly replied: "If we had stayed, we would have ended up at the tractor plant, too." And not a word more.

Now that I know much more about the Holocaust, I can only thank the Creator that my great-grandmother Berta Markivna, my great-grandfather Boris Moiseevich, and their 16-year-old daughter Yulia, my future grandmother, miraculously managed to evacuate to Alma-Ata and did not end up in that terrible stream.

I bought these photos for 150 euros from an anonymous seller in Germany at an online auction. Previously, there was not a single photograph of the murdered Kharkiv Jews who embarked on their last journey in mid-December 1941. Now, these pictures lend them visible outlines, pulling them back from oblivion.

Text: Shimon Briman (Israel).

Photos: Shimon Briman's private collection.