Kai Struve: "Coming to terms with the past, especially the Holocaust, should be a constant reminder to champion a democratic and tolerant society"

The role of Ukrainian nationalists in the Holocaust is a question that figures prominently in Russian propaganda. The following interview with the German historian Kai Struve, a specialist in anti-Jewish violence in Ukraine, focuses on the pogroms in the summer of 1941. In 2022, Dukh i Litera Publishers released his book about anti-Jewish violence in Eastern Galicia in the summer of 1941 and the role of OUN members in these processes. We also discuss the book's key findings and the basis of the main myths generated by the Russian propaganda machine, which frequently instrumentalizes these historical events.

"A Ukrainian victory in this war could be an important contribution to overcoming the past"

Since we are publishing this interview in the column" Overcoming the Past," my first question pertains to the importance of this notion. What does "overcoming the past" mean to you?

There are at least two treatments/meanings of the term "overcoming the past." First, this concept is derived from the German term Vergangenheitsbewältigung (overcoming the past), which was quite popular in the 1950s–1980s. It describes the process of examining, understanding, and discussing the mass crimes of the National Socialist regime in German society. But in recent decades, this term has mostly fallen out of use because, in a certain sense, it signifies, at least in German, a process that has some kind of completion. In other words, the term suggested that German society should confront the crimes of the past and then we can forget about them. Many people believed that this is not the conclusion to be reached. Instead, the mass crimes of the past, particularly the Holocaust, should be a permanent reminder to champion a democratic and tolerant society. Another meaning of this concept, which Yaroslav Hrytsak proposes in his recent book in the Ukrainian context, resides in the fact that Ukraine should rid itself of past structures that have limited positive development throughout the decades of Ukrainian independence. Hrytsak also argues that understanding and interpreting history is vital in this process.

I think that, in the context of the current war, the term "overcoming the past" can also have a third meaning. To a significant extent, the Russo-Ukrainian War pertains to the imperialistic ideas, perceptions, and traumas of the past and, more importantly, the lack of a real reckoning with Soviet crimes and the evil nature of the Soviet regime in Russian society. In this sense, a Ukrainian victory in this war could be an important contribution to overcoming the past.

Some historians believe that Ukraine is still hostage to its historically inconvenient status as the borderland of European civilization, a zone of confrontation with Russia. How can we rethink the past, considering this borderland location?

The current war raises many questions for historians and casts doubt on many earlier convictions. These questions pertain less to Ukrainian historians and more to Western scholars and the Western public. Obviously, the most serious questions are those for Russian historians, but we will not address that problem right now. Western historians (most noticeably in North America, but also in Germany) began to discuss the problems of a prevailing Russocentric perception of Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union in the Western and international scholarly milieus more seriously after the Russian invasion. This Russocentric approach led to disregarding other national histories, linguistic cultures, or non-Russian experiences. Many discussions are taking place today about the decolonization of academic studies that deal with research on this region, including in the field of history. In any case, I believe that one of the consequences of today's war will be a more critical approach to studying Russia and the Soviet Union with regard to their character as empires, as well as greater attention will be given to the experiences, perspectives, and voices of the non-Russian peoples.

I also think that Germany and other Western countries must devote more attention to the Soviet regime and its mass crimes. Here it is not so much a question of historical research — obviously, it exists, and the overall situation is not bad with regard to research, even though there may be some lacunae. Rather, it is a matter of public awareness and the culture of memory.

Today, the long shadow of the Second World War plays a vital role in the information confrontation with Russia. On the one hand, Russia is using Soviet myths about this war in its anti-Ukrainian propaganda. On the other, we observe the power of the discourse about the Second World War in Ukraine's media sphere. We often hear statements from people and the media, like "worse than the Germans" and "fascists/Nazis," the latter giving rise to the word rashysty (Ruscists) used today to define the aggressor's actions. What can this discourse indicate? How legitimate is today's use of the concepts formulated to describe the events of the Second World War? Do you think that the current war can alter our perception of the Second World War in general, particularly of the Holocaust?

Here, we have several important but complex issues, and I think we'll have to deal with these questions not just in this year, but maybe the next decades. I will begin by addressing the last question because it is the most fundamental one. In Germany and in the Western public, the Holocaust and Germany's mass crimes during the Second World War are at the center of the history of the twentieth century. In a sense, they are regarded as a negative symbol of twentieth-century history, as the German philosopher Jürgen Habermas put it in the mid-1980s. On the other hand, Soviet mass crimes have received much less attention. However, if we look at German or, more broadly, Western discussions over the past ten to fifteen years, we can see certain changes there. This means that attention to Soviet mass crimes is slowly increasing due to the influence of Eastern European countries, including Ukraine. I think this process has accelerated significantly because of Russia's war against Ukraine. For example, the German Bundestag recognized the Holodomor of 1932–1933 in Ukraine as a genocide in November 2022. This resolution also emphasizes that Soviet mass crimes are part of our shared European history.

At the same time, in Eastern Europe, the history of the Holocaust gained increased public attention only in the 1990s. For the last fifteen years, we have observed growing attention to the Holocaust in the mass consciousness of Ukrainian society. I'm sure this will continue — at least it should because Ukraine, Poland, Belarus, and Lithuania are countries where mass killings of large numbers of European Jews took place and where most of the Jews who perished lived before the Second World War. That is why the Holocaust had the greatest impact on these parts of Eastern Europe.

"I prefer the more neutral terms 'anti-Jewish violence' and 'violence against Jews' to 'pogrom'"

In our challenging times, is it worthwhile to discuss Holocaust-related questions that often include various difficult aspects, such as the participation of local organizations and local populations? Can this play into the hands of Russian propaganda? Given the context of the Russo-Ukrainian War, how do we talk about this topic today without causing harm or avoiding objectivity and a necessary discussion?

Putin did not invent this accusation of "Ukrainian Nazis" ("denazification" as one of the stated goals of the current war). It is only the latest expression of the Soviet enemy image of Ukrainian nationalism and its identification with "fascism." An analysis of this image would be another task for historians. It still plays a vital role in Russia. One can even assume that it influenced Putin's decision to start the war because this decision was obviously based on very faulty ideas about Ukraine and Ukrainian society, especially his idea that Ukrainian nationalism and the Ukrainian striving for independence are not deeply rooted in Ukrainian society. All this is part of the traditional Russian and especially Soviet enemy image of Ukrainian nationalism. Also, in Ukraine, after its independence, views from Soviet times continued to be influential. This was part of a conflict in Ukrainian society between the national view of history and the view strongly influenced by Soviet elements. Russia used this Soviet tradition as part of a strategy to keep its influence in Ukraine.

One aspect of the Soviet image of the "enemy" lies in equating Ukrainian nationalism with all forms of Ukrainians' wartime collaboration with the Germans during the occupation. Obviously, this also blurs the differences between various Ukrainian actors and denies the fact that the OUN(B) 's collaboration with the German side collapsed to a significant degree by the second half of 1941.

However, I don't think that Russian propaganda should prevent us from discussing collaboration-related questions. In fact, it seems to me that the fact that within Ukrainian society, the strong political polarization that was related with them largely disappeared in 2014 when Russia's manipulations and instrumentalization of these subjects became more than obvious opens up the possibility for more serious discussions of these questions. Of course, the Soviet image of the "enemy," which Russia instrumentalized in 2014 and even more so in 2022, is a manipulation and falsification. Nevertheless, it is obvious that collaboration did occur, just like the nationalists perpetrated crimes. I hope that there will be a better opportunity now to discuss these problems than there was earlier, when the Soviet narrative of the "Great Patriotic War" and the image of the "enemy," linked to Ukrainian nationalism, were still influential in Ukraine as well.

The Ukrainian translation of your book Deutsche Herrschaft, ukrainischer Nationalismus, antijüdische Gewalt [German Rule, Ukrainian Nationalism, Anti-Jewish Violence], which examines the anti-Jewish pogroms in the summer of 1941, was published in 2022. According to your findings, most of these pogroms were not spontaneous but organized. Who exactly bears the ultimate responsibility for organizing the pogroms in Eastern Galicia?

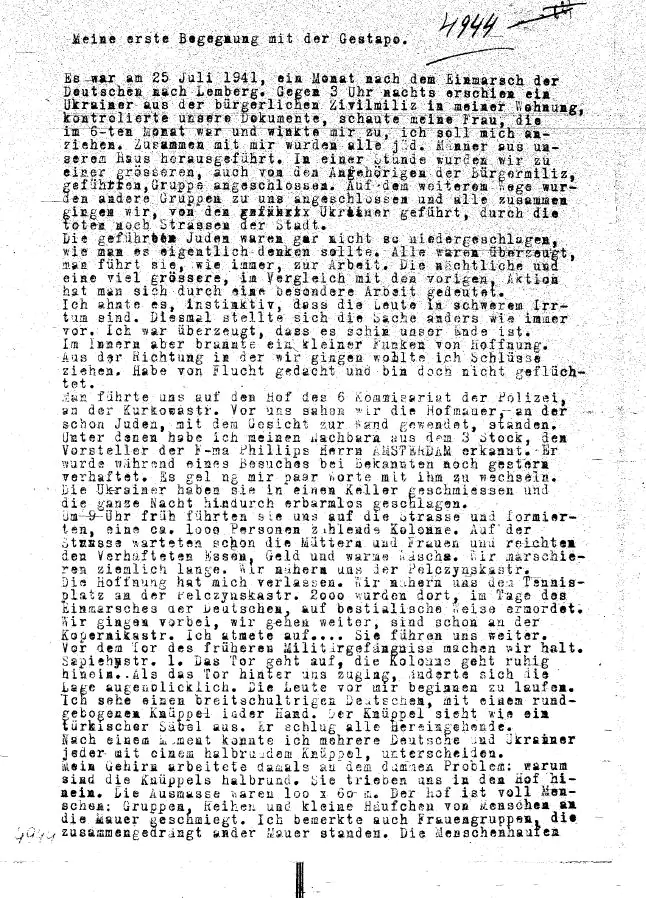

In my research, I prefer to use the more neutral terms "anti-Jewish violence" and "violence against Jews" rather than "pogrom." I argue that when we understand the term "pogrom" as describing mostly spontaneous violence, i.e. as riots against Jews, a substantial part of the violence that occurred during the indicated period, with the participation of local people, cannot, in fact, be called a pogrom. Such an image of the anti-Jewish violence as riots was mostly created by the events in Lviv on 1 July 1941. They strongly influenced the general image of violence against Jews from the local side in these days that took place also in a number of other places, but had often had a different course. The events in Lviv had such a strong impact on the image of the anti-Jewish violence in July 1941 because of the large number of sources, most importantly Jewish testimonies, photographs and even filmed materials. There were also some smaller cities where the violence unfolded in a similar fashion, for example, in Boryslav and Sambir.

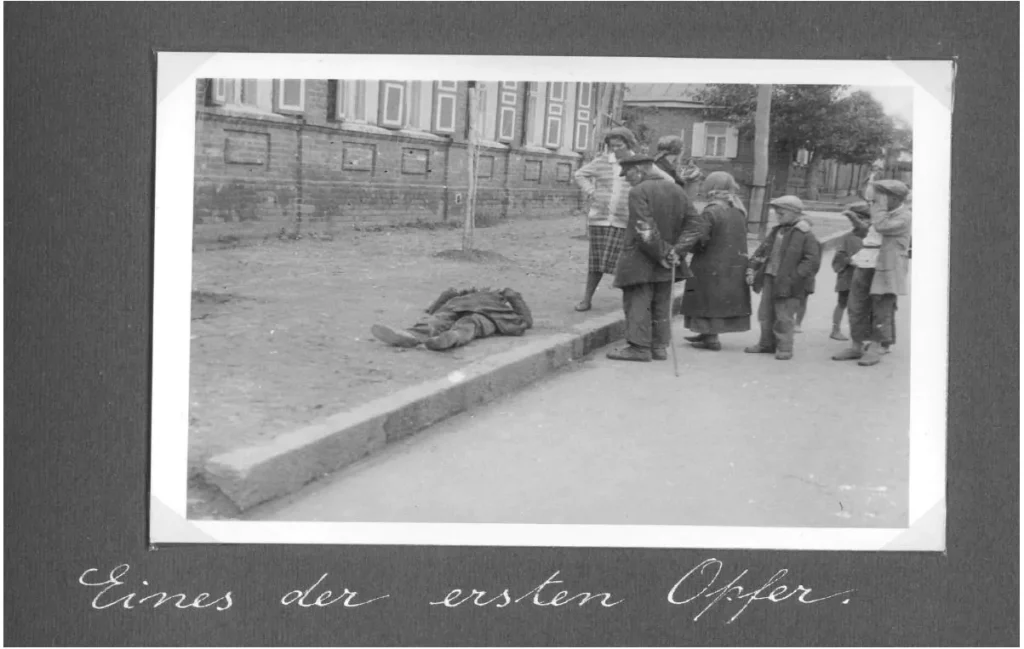

However, a lot of violence occurred in villages and small towns, but it did not have the character of a largely spontaneous public riot. Instead, targeted murders took place in the form of executions of people, selected in advance, who were regarded as accomplices of the Soviet government. The perpetrators of the crimes were OUN combat groups that had been waging a clandestine struggle against the Soviet authorities and had created local militias at the beginning of the German occupation. In many cases, not only Jews were killed, but also Ukrainians and Poles, who were branded as "traitors." But it was rare that families were killed. In contrast, entire Jewish families were often murdered.

Jewish memoirs and testimonies often call these attacks "pogroms." But if we look more closely, it is evident that specific, pre-selected families or people were being killed, and other Jews were left unharmed. This often took place at night; in other words, these were not events designed to attract public attention, and the perpetrators did not act spontaneously. In certain locales, small groups of people were arrested, brought outside the village or town, and shot or killed in some other way. These targeted executions were part of the process marked by the change of power from Soviet to German or Soviet to Ukrainian rule and the establishment of control over certain locales as part of the OUN's attempt to build a state during this period.

In cases where pogroms were spontaneous, what were the motives of the Ukrainian participants?

Of crucial importance was the identification of Jews with the Soviet regime — the antisemitic stereotype of Judeo-Communism, according to which Jews were perceived as a group that supported the Soviet authorities and thereby received benefits. During the period marked by the transition from Soviet to German power (or to Ukrainian, as many people hoped), this was one of the ways to "punish" Jews for the crimes of the Soviet regime. In some instances, specific individuals were targeted; in others, punishment took the form of a general attack against Jews with larger spontaneous participation. Public violence mainly occurred in areas where the Soviet authorities had murdered prison inmates before their withdrawal in the first days after Germany's invasion on 22 June 1941. In this regard, Lviv is the most important case. Jews were brought to three large prisons in the city, where the Soviets had killed approximately 2,700 prisoners the week after 22 June 1941. On the Germans' orders, the local militia, created by the OUN, herded Jews there to perform forced labor: extract corpses from the cells and mass burial sites located in the prison courtyards. Jews were attacked right in the prison building or on nearby streets. Another feature was that significantly more Jews than were necessary for this kind of labor were dispatched to the prisons, led there by the militia as well as local residents, who joined in spontaneously. The forcible assembly of several thousand people next to a prison was in and of itself a form of punishment, and the attacks, beatings, and killings of Jews were a form of public humiliation and punishment for the alleged crimes of Jews during the period of Soviet rule.

Another mass murder of Jews took place in Lviv on 25–27 July. A Russian-language article in Wikipedia still calls these events the "Petliura days" and defines them as a pogrom. What exactly were these so-called "Petliura days" in Lviv?

It is not just the Russian-language Wikipedia that describes the so-called "Petliura days" of 25–27 July 1941 in Lviv as Ukrainian pogroms. Such a description appears in many older publications claiming that this event resembled the pogrom in the beginning of July 1941. Looking more closely, it becomes clear that this was not a "pogrom" like the one on 1 July 1941. In fact, the Germans executed approximately 1,500 Jews on 26–27 July. Prior to this mass execution, the Ukrainian militia was arresting Jews and taking them to the prison on Łącki Street, and from there, the German Security Police brought them to the city outskirts, where they shot them. The misreading of the events of 25–27 July 1941 as a pogrom may be connected with the fact that also, in the beginning of July 1941, there were two different phases of violence and murder. Often, Jews' recollections and memoirs do not clearly differentiate between them. In addition to the pogrom of 1 July 1941, the Germans carried out a mass execution on 5 July 1941. Most of the Jews who died on these days were killed during this mass execution, probably about 2,000. During the two days before the execution, the Ukrainian militia arrested and assembled them on German orders in a stadium next to the prison on Łącki Street. In their testimonies, numerous witnesses do not make a clear distinction between the events of 1 July and the subsequent days leading up to 5 July because there were many similarities. On 1 July as well as before 5 July and during the "Petliura days," the Ukrainian militia had arrested the Jews and brought them to the prison building. But, unlike on 1 July, there was no great explosion of street violence neither on 3 and 4 July nor on 25-27 July. Thus, the events of 25–27 July are very similar to what took place in relation to the mass execution of 5 July 1941, but not the pogrom on 1 July.

"It was mostly men who were both perpetrators and victims of violence during the events in early July 1941"

You investigated the course of the pogromist operations/pogroms in Eastern Galicia. However, we know that a number of pogroms also took place on the territory of Western Volyn. Did you try to draw any parallel between the pogroms in Eastern Galicia and Western Volyn, as well as the Baltic countries?

The events that transpired in all these regions, except Belarus, are pretty similar. This also pertains to Volhynia, where, as in Eastern Galicia, the OUN played a very important role. Just like the OUN(B) in Galicia and Volhynia, there were insurgent groups in the Baltic countries. The events in Lithuania most resemble those that took place in Eastern Galicia. There were underground groups in Latvia as well, and in both countries, they launched their insurgent activities in cooperation with the Germans after Germany attacked the Soviet Union. There were also many similarities with the anti-Jewish violence in northeastern Poland, which were vigorously discussed in the context of Jan Tomasz Gross's book Neighbors on the Jedwabne case. Although the events in Jedwabne and its vicinities are often interpreted as an outbreak of spontaneous violence, sources clearly indicate that there was an underground also operating in this region — in this case, Polish — that was fighting against the Soviet authorities and collaborated to some extent with the Germans during Germany's attack on the Soviet Union. Just like in other regions, underground members took control of local administrations, formed a militia in the cities and towns from which the Soviet army had retreated, and began in their own way to punish those whom they identified with the Soviet power. After German police units had arrived in the region, they encouraged this course of events. All this led to grave consequences, like in Jedwabne. One exception is the Belarusian territories, where there were very few localities where the Belarusian population committed violent acts against Jews. I believe that the reason for this is that there was not a strong Belarusian anti-Soviet insurgent movement supporting the German attack on the Soviet Union.

How do you identify the gender and age dimensions of pogrom-related violence? What was the ratio of men to women among the victims and male to female participants in such violence? What role did sexual violence play? You write that adolescents between the ages of 12 and 15 played a role in the pogroms. What functions did they perform? In your opinion, why did they become involved in the violence of the pogroms?

It was primarily men who were both perpetrators and victims of violence in early July 1941. In Lviv and some other places where spontaneous involvement of local residents was significant, women were not only victims, but also perpetrators. Nevertheless, photographs of female victims of the Lviv pogrom became a kind of iconic images of the Holocaust since their first publication in the 1960s. These photographs show people stripping women of their clothing to humiliate them. Other forms of sexual violence against women, including rape, were committed. But on the whole, the number of rape reports is quite small. There is not enough evidence indicating that this was a mass phenomenon in the summer of 1941, in contrast to the pogroms that took place in other periods, for example, in central Ukraine in 1919.

As for the question of adolescents' participation, there are few sources about the Lviv pogrom proving that young people committed violent acts against Jews. I think we can only speculate here about the context and motives behind their involvement. But it makes sense as these riots, at least in the form in which they took place in Lviv, bore some similarity to the anti-Jewish pogroms of previous centuries. The violence in Lviv on 1 July 1941 can also be understood as a form of public punishment for violations of the boundaries of the established order as perceived by the Christian population. These "violations" were committed during the period of Soviet power, and the attacks were supposed to remind Jews about their place in society, which, in a traditional Christian view, could only be a position of subservience. Many Ukrainians and Poles believed that Jews had transgressed these boundaries during Soviet rule after September 1939. For the Middle Ages, the research literature reveals/shows that such public rituals often took place during Eastertime when, for example, Christians were throwing rocks at synagogues or at the walls of Jewish quarters. Often, children or adolescents committed such acts. In other words, this was a kind of ritual that reminded Jews that they held a subordinate position in society and that they could not transgress established boundaries.

"In the history of twentieth-century Europe, there were two extraordinarily criminal regimes: the German National-Socialist regime and the Soviet regime"

Earlier, you spoke about the discussions around the decolonization of Eastern European studies in general and historical studies in particular. Can something be done in this direction regarding the history of the Holocaust? Are researchers raising such questions in this area?

I don't think that it is a question of studying the Holocaust in the Nazi-occupied territories of Ukraine or the former Soviet Union as such. Rather, the current war raises questions about the memory of the Second World War and the Holocaust, mainly in Western societies, and its interrelation with the memory of Soviet mass crimes. Here, basic features developed during the Cold War also remained influential in the subsequent decades. Paradoxically, awareness of Soviet mass crimes and attention to them faded into the background in Western societies during this period. Even today, we are still feeling the effects of the Cold War on the memory of the crimes that were committed by both of these regimes. A fresh analysis of such questions is becoming increasingly indispensable because it is evident that Russia's war against Ukraine became possible also due to the lack of a truly critical assessment of Soviet mass crimes and Soviet imperial traditions in Russia and to the manipulation of the history of the Second World War.

A fresh analysis of such questions is becoming increasingly indispensable because it is evident that Russia's war against Ukraine became possible also due to the lack of a truly critical assessment of Soviet mass crimes and Soviet imperial traditions in Russia and to the manipulation of the history of the Second World War.

Two main reasons contributed to Western societies paying comparatively little attention to Soviet mass crimes in the history of twentieth-century Europe. On the one hand, this has to do with the fact that those who, during the second half of the twentieth century, in controversial debates about German mass crimes did not want to attach key importance to the Holocaust for the history of the twentieth century not rarely referred to Soviets' mass crimes as justification. One example that I can cite here is the German "historians' dispute" of the 1980s, when one of the central figures in this dispute, Ernst Nolte, called the GULAG a more "original" crime in comparison with Auschwitz. One of the consequences of these discussions/controversies was that the thematization of Soviet mass crimes was frequently viewed with suspicion, even when its real goal was not to relativize the Holocaust.

The second reason is the political conflicts that took place in Western societies about relations with the Soviet Union during the Cold War. Many supporters of détente viewed highlighting of Soviet mass crimes as an attempt to end this policy and ramp up the Cold War.

Where Ukraine is concerned, both of these factors had a significant impact on the memory of the Holodomor. When Ukrainians in North America since the 1980s tried to attract larger attention to it, this helped ensure that this greatest Soviet mass crime would remain unnoticed in Western societies also in subsequent decades. I believe that the history of memory also needs a rethinking because, as a result of the current war, it is becoming increasingly evident that in the history of twentieth-century Europe, there were two extraordinarily criminal/murderous/genocidal regimes: the German National Socialist and the Soviet. In this discussion, Ukraine, the country that suffered the most from the mass crimes of both these regimes, can play a key role.

Why do such figures as Volodymyr Bemko (who formed a Ukrainian-Polish-Jewish committee in 1939 to stop the violence that erupted in Galicia in September 1939 and who, in his capacity as a lawyer, helped OUN members and other Ukrainians to survive the German occupation) remain unknown in Ukrainian society and the diaspora? I also have a question about methodology. Is the deorientalization of Holocaust studies possible in Ukraine? In other words, is it possible to count among Holocaust victims not just Jews but also members of small ethnic groups, such as the Krymchaks and the Karaites? Is it possible to view not only the Christian Slavic population as perpetrators but also, say, the Volga and Crimean Tatars, who also took part in persecuting the Jews (Yuri Radchenko)?

These questions are truly worth studying. As for your first question, when considering events in the summer of 1941, there were indeed OUN members who protected Jews by saving them from persecution. Historians studying such topics encounter an intricate diversity of the past, replete with many different experiences and behavior patterns. Reflecting these complexities in historical works is an important task in the work of historians.

How important is it to research the phenomenon of the Righteous Among the Nations using culturological and deorientalizing approaches (Yuri Radchenko)?

We must honor the memory of the people who risked and sometimes lost their lives in order to help others. Thus, it is essential to research their stories and motives. This includes the issue of various cultural contexts and affiliations that were frequently different or more complex in Ukraine than in Western Europe. However, as the controversial discussions of recent years in Poland have shown, this question can sometimes cross the fine line between the memory of people whom we consider exemplary today and the instrumentalization of their stories to deflect attention from questions about the local population's involvement in the Holocaust. In my opinion, some of these accusations are exaggerated; nevertheless, this is one of the contexts of the discussion.

Has the Russo-Ukrainian War had an impact on your position and your studies? Has it affected your research focus and methodological approaches in any way?

This war is affecting research in several ways. In 2022, I was planning to start a new research project, but the war complicated this process. More importantly, this war will change our view of history, especially the history of the twentieth century. During this period of acute political changes, many new and important questions about history arise. For example, back in 2021, it was difficult to imagine that the Bundestag would adopt a resolution like that on the Holodomor that I mentioned above. This attests to changes of views and discussions in the public resulting from this war. Clearly, this affects mostly the public and historical studies in western countries, where many of the questions that have been current in Ukraine for many years are emerging only now. Overall, the war is having an impact on the types of questions that will be important for historians in the future.

Interviewed by Petro Dolhanov

This text is an expanded version of the transcript of an interview that took place on 29 November 2022 as part of a series of online seminars on "Overcoming the Past."

The photographs are from the author's personal archive and open sources.

Kai Struve is a historian and Research Fellow at the Institute of History, Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg (Germany). [email protected]

Kai Struve is a historian and Research Fellow at the Institute of History, Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg (Germany). [email protected]

Originally appeared in Ukrainian @Ukraina Moderna

This article was published as part of a project supported by the Canadian non-profit charitable organization Ukrainian Jewish Encounter.

Translated from the Ukrainian by Marta D. Olynyk.

NOTE: UJE does not necessarily endorse opinions expressed in articles and other materials published on its website and social media pages. Such materials are posted to promote discussion related to Ukrainian-Jewish interactions and relations. The website and social media pages will be places of information that reflect varied viewpoints.