Laughter against the background of chaos, or how to survive in a city where there is constant shooting

We are talking with the historian Tetyana Batanova about Kyiv in 1919, and the satirical novel written by the Jewish writer Der Tunkeler.

In 1917, strikes and rebellions in St. Petersburg led to the fall of the monarchy. For Ukraine this meant the beginning of a change of revolutionary events that gave rise to the Ukrainian National Republic. Over the next few months the Ukrainian Central Rada failed to form an adequately manned and trained army in order to defend its territory from the incursions of the Bolsheviks. After their short-lived stay in Kyiv, the city fell under the control of Pavlo Skoropadsky and German army units. When the war ended and the Germans departed from the territory of Ukraine, the Hetmanate collapsed. In late 1918 chaos erupted, and Kyiv passed from one regime’s control to another.

Thousands of Kyiv residents lived in these conditions, including the Jewish writer Yoysef Tunkel, who wrote in Yiddish under the pseudonym Der Tunkeler. At the beginning of the twentieth century he was known as a caricaturist and illustrator of satirical pages of newspapers published in Warsaw, Cracow, and New York.

This Jewish writer from Belarus, who suddenly appeared amidst the chaos unfolding in Ukraine, is the subject of my conversation with Tetyana Batanova, a historian and professor of Jewish Studies at National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy (NaUKMA). At a conference on “The Jews of Ukraine: Revolution and Postrevolutionary Modernization,” organized by the Ukrainian Association for Jewish Studies of NaUKMA, she presented a partial Ukrainian-language translation of Yoysef Tunkel’s text.

Tetyana Batanova: Der Tunkeler landed in Kyiv at the beginning of 1917. In the first chapter of his autobiographical novel, The Adventures of Benjamin the Fourth (from the Ukrainian Chaos), he writes that he spent two years in Kyiv and that this was a glorious and luxurious city, except that there was constant shooting there. Then he writes about the various events to which he does not assign any concrete, chronological dates. It is not his task to document and recreate the chronology, like a historian. He is writing this for his contemporaries. All these events in Kyiv are known to everyone in general. In his texts, events are mixed up. For example, his writings depict forces that were never based in Kyiv, but may have fought for the territory of Ukraine, for example, in the south, and threatened Kyiv that they would arrive and capture the city. I am talking about the various otamans, White Guard commanders, and others. And Tunkeler’s work features all these heroes as well as Kyiv: the 77 individuals and armies that are fighting for Kyiv.

And this chaos is advancing toward the city. The Bolshevik army first arrives in Kyiv in January 1918, and the Ukrainian Central Rada has to abandon Kyiv. The Bolsheviks come to Kyiv in a major way a second time in 1919. And at this very time Der Tunkeler begins writing his satirical novel. We see such new Soviet phenomena as the ochered [Rus. “queue”]—Der Tunkeler uses this exact word—as well as food ration cards and passes.

The hero says very little about himself. He walks to work. In fact, he does not walk but crawls, because there is shooting all around. What is his job? He works in some kind of essential institution because, as he writes, it is necessary “to build up production” in the new country.

Andriy Kobalia: This is very reminiscent of some kind of Orwellian “New-speak.”

Tetyana Batanova: Yes, he actively uses this new language, this New-speak. He works in an institution that is supposed to register citizens who do not have the right to obtain food with cards, and he is supposed to register them as truly not having obtained such foodstuffs. It’s an absurd situation. We see ochereds at all possible institutions. And when Tunkeler realizes that everyone here is shooting non-stop and that perhaps it might be safer for him to get out of Kyiv, the most interesting part begins. Because how can he get out of Kyiv? You need to get a propusk [pass]! And in order to obtain a propusk, you need to stand in line. And in order to stand in line, there is a separate line, where things are written down in order to stand in line. Then it turns out that the Cheka has seized the premises of another institution—the TsK [Central Committee]. And nobody knows where the TsK, which issued passes previously, has gone. It’s a good thing that our hero has a daughter, who has a boy who is courting her. This boy has a distant relative, who also has a relative who works in an institution that will issue passes.

Tunkeler pokes fun at institutions. He decodes Kolgorkhoz as “Colonial Urban Economy.” No such institution could have existed, but he plays with this and shows all that absurdity. And a pass is not issued just to anyone. A person has to be sent on a business trip, a komandirovka. For example, there is a lack of paper in all institutions. So, you can go to a relative with pull, so that you will travel to Belarus, for example, and bring paper to the new Soviet institutions, so that there will be something on which to write. The fun doesn’t end there because you also have to have a smallpox vaccination. It was in the spring of 1919 that the Soviet government issued a directive about mandatory immunization for the entire population. And this is a kind of signpost. We can figure out when the events of the storyline took place.

Andriy Kobalia: Are there any markers that indicate the period?

Tetyana Batanova: We have mentions of the infamous Kurenivka peasant uprising and the Mezhyhiria tragedy. The Kurenivka uprising was a rebellion mounted by several villages around Kyiv, whose participants rose up against the Bolsheviks and the collection of taxes in kind. In response, the Soviet government sent Chinese troops against them. In those days there were “international detachments” in the Soviet army, including Chinese ones, which fought on Ukrainian territory.

Andriy Kobalia: To what extent does the plot echo the life story of our author? Do we know what he was doing in those months? In this context, I should mention another Jewish writer, Sholem Aleichem, whose texts contain many autobiographical details, like the migration of Jews from small towns to large gubernial cities, and the pogroms of 1905, and various characters. Is he really the hero of the text?

Tetyana Batanova: In the finest satirical manner, Der Tunkeler tries to give the least amount of information about himself. This is done so that each person who reads this novel in Warsaw, in New York, or in the lands of the former Russian Empire will recognize himself in the whirlwind of revolutionary events. He does this deliberately. However, according to what Tunkeler writes, we see that he was in Kyiv. This is his own satirical nature. By the time he abandoned Kyiv, he had managed to publish a satirical magazine called Ashmedai (the demon-tempter). Several copies are held in the Jewish Studies collection of the National Library of Ukraine, with beautiful illustrations and caricatures. There we also see caricatures of Jewish party leaders and Hetman Pavlo Skoropadsky, who asks [Kaiser] Wilhelm: “What am I to do now and where do I flee?” And it was precisely in December 1918 that he flees under pressure from the Directory’s troops and other armies.

If you compare Sholem Aleichem and Der Tunkeler, it must be said that the former leaves the territory of Ukraine after the pogroms of 1903 and 1905. At first he lives in Europe, then he lands in New York. Something similar happens to Der Tunkeler. But it’s worth mentioning that he roamed his entire life. And this novel is a manifestation of his and everyone’s wanderings and the fate of numerous emigrants: Jews, and Ukrainians, and other nationalities that fled from historical upheavals, wars, and revolutions, and immigrated to other countries.

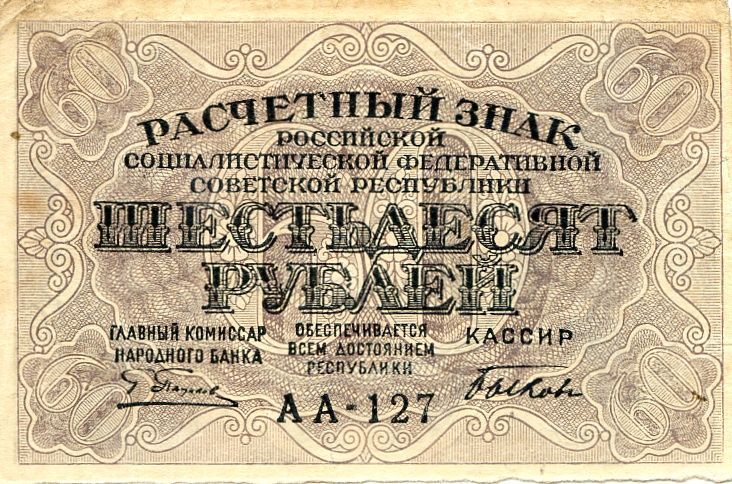

Each chapter tells us about some aspect of daily life. About the currencies of various governments; these currencies are circulating in large quantities in Kyiv. And not just currencies but also counterfeits of these currencies. We see the renaming of streets in later chapters. We see how people communicate with each other, how the trains run during this period, how each citizen in 1919 has become so disillusioned that he is capable of seeing a counterrevolutionary in his neighbor standing around the corner. And why him? And why is he simply standing around like that? Or why is he shooting into the street? I will shoot at him! And it’s like that at every step of the way. In other words, 1919 is a terrible year for everyone, including Jews. We also see mentions of the Mezhyhiria tragedy, when otaman chieftains captured two steamboats on the Dnipro River. They released the Christians from the steamboats, and drowned the Jews. Just like that.

Andriy Kobalia: When I was reading the text, I noticed that Der Tunkeler sometimes mixed up streets. For example, from Volodymyrska Street he goes straight to Khreshchatyk. But this is impossible, both today and then. Why does he make these mistakes? Does he not know his way around Kyiv, does he have a poor grasp of the politics of the time? Is the background simply more important to him than facts?

Tetyana Batanova: What is more important for Der Tunkeler here is not the chronology of events but conveying the revolutionary chaos. On the other hand, a reader from Warsaw or New York does not know that you can go from Khreshchatyk to some other narrow street or elsewhere. He knows that it is one of Kyiv’s central streets, although at the time it was not the most central one. He conveyed everyday life, which meant that you did not know what the next day would be like; what army would come and want to smash the Jews. All the armies fought against each other. And, as Der Tunkeler writes, they might not even agree on the Jewish question. One army near Kyiv says: “All the Jews should be slaughtered! All 30,000!” These are conditional numbers. Later another army arrives and says: “No, we don’t agree with them. Thirty [thousand] is too much. Twenty [thousand] is enough.”

That’s how he shows what the ordinary citizen feels. About the hero, we know that he is approximately middle aged; like most people like this, he has a wife and a few children. But we do not know their names. He seeks to underscore this “averageness” so much that anyone will be able to relate to this.

Andriy Kobalia: If you look at the plot, all of it is very reminiscent of an escape. The hero tries to acquire a pass, then a pass for a pass for yet another pass. And later it turns out that he has to go to another place. And he tries to break out of Kyiv, for the sake of which many regimes are fighting. So far you have completed only a partial translation of the text. Does Benjamin the Fourth manage to escape?

Tetyana Batanova: Nowhere does he call his story an escape. The main objective here is not to escape but to advance toward the goal—of wandering. He writes about himself as the biggest wanderer in the world. He mentions Columbus and the explorers of the North Pole, who quarreled with each other in the USA in 1908. If Columbus had needed to obtain a pass, where would he have reached? Or if he had had to take care of his beard? Columbus shaved before his travels, and he returned with a long beard. For a Jew, having a beard in 1919 put the fear of God in you. You were instantly identified as a Jew. Any bandit calling himself a revolutionary would have a problem with him and would take something. A beard is an attribute that a Jewish wanderer needs either to shave or tie up.

He could have been hunted, mobilized to dig trenches. The Bolsheviks accused him of being an “independentist,” a reference to the Ukrainian Central Rada. Ukrainians could have caught him as a zhyd [the traditional Ukrainian word for “Jew,” unlike its Russian counterpart, which is customarily rendered as “Yid”—Trans.]—he uses this word whenever necessary. Jewish socialist parties reorient themselves on the Soviet power, they are creating a communist union, and later they merge with the Communist Party of Ukraine. So they catch him as a Zionist, although Der Tunkeler himself did not belong to any parties. The fear here is that you are being caught as a counterrevolutionary.

The main thing is not to escape but to wander and advance toward the goal. The main thing is not to lose your spirit. Will he escape from Kyiv? That’s not important. He maintains his cheerful spirits and laughter. And this is his only companion. Unlike Benjamin the Third, who had his own companion, owing to which he was called the Jewish Don Quixote, Benjamin the Fourth does not have a companion. We cannot even consider the Lord as such a companion, although he constantly utters “Vidui,” the prayer before death, because all around people are shooting. But we do not have the attributes of keeping the Sabbath.

His companion is laughter. He laughs in all situations. And I think that this is inherent in Ukrainians during periods of revolutionary events. If we recall the Maidan, the absurd aspect was present nearly always, with the exception of the most terrible events. But an absurd-carnival culture is an attribute of Ukrainian culture. And Tunkeler depicts Kyiv with love. He begins with [showing] that it is a glorious city. And he wants to run away, not because he does not love Kyiv, but because this luxurious city is being transformed into something chaotic, terrible, and incomprehensible.

This program was made possible by the Canadian non-profit organization Ukrainian Jewish Encounter.

Originally appeared in Ukrainian (Hromadske Radio podcast) here.

Translated from the Ukrainian by Marta D. Olynyk.

Edited by Peter Bejger.

NOTE: UJE does not necessarily endorse opinions expressed in articles and other materials published on its website and social media pages. Such materials are posted to promote discussion related to Ukrainian-Jewish interactions and relations. The website and social media pages will be places of information that reflect varied viewpoints.