Life and death of the Jewish communities in western Volyn (pt. 1)

The series of semi-academic publications entitled The Life and Death of Jewish Communities, issued in 2023, examines the Holocaust as it unfolded in various cities and towns of Ukraine. The following article seeks to interpret and contextualize the main findings of this series of Holocaust microstudies in one specific region: western Volyn. In Part 1, Petro Dolhanov analyzes the historiographic importance of this publication series and describes the sources he consulted while preparing individual volumes.

Petro Dolhanov

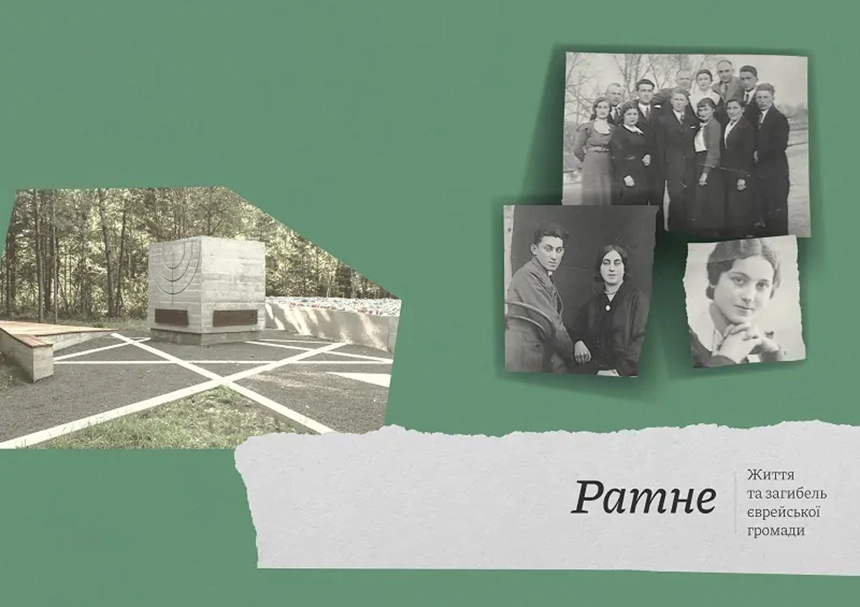

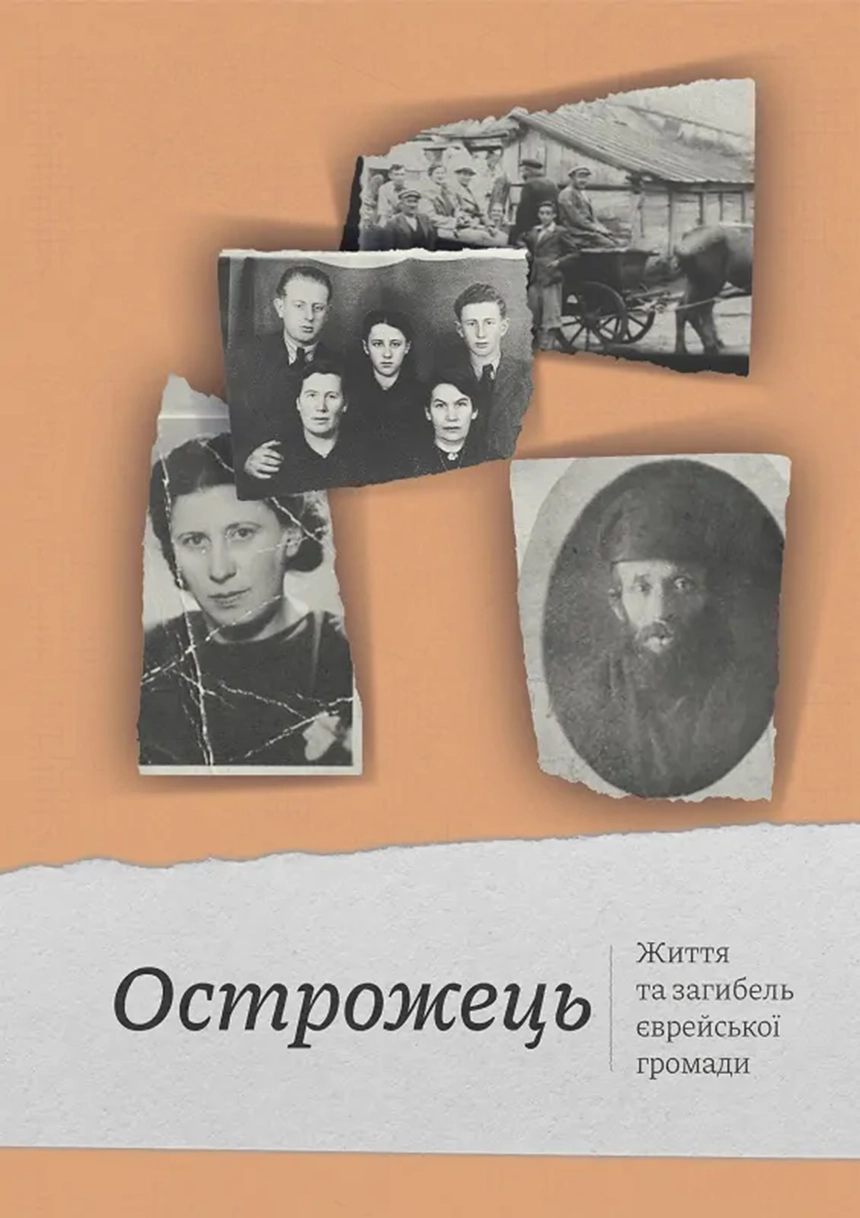

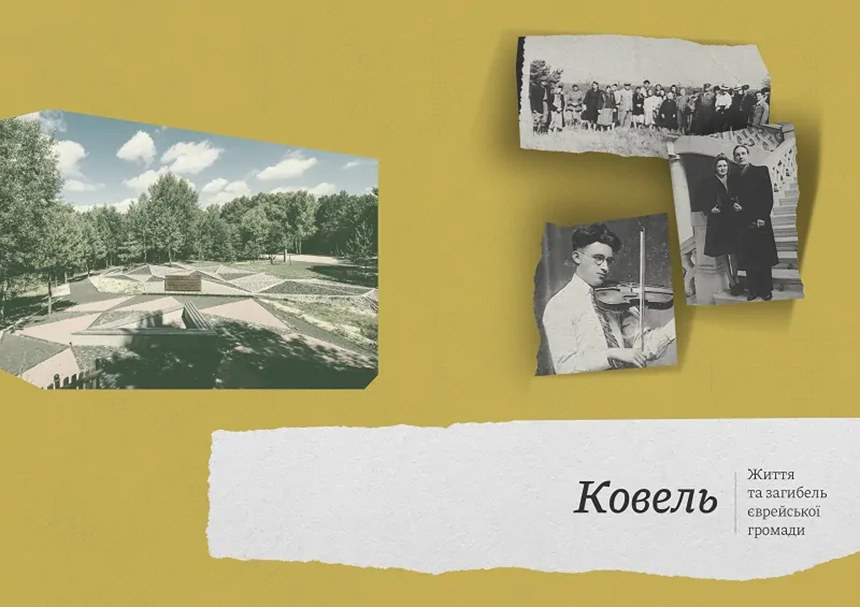

The series The Life and Death of Jewish Communities, aimed at broadening the horizons of our understanding of the history of the Holocaust in western Volyn, one of Ukraine's historical and cultural regions, is part of the Connecting Memory project. [1] The individual volumes focus on the Shoah as it enfolded in small towns and villages in western Volyn, some of which turned into hamlets after the Second World War: Holoby and Melnytsia, Kysylyn, Кovel, Мizoch, Оstrozhets, and Ratne. This author researched and prepared all but one of these studies; Roman Mykhalchuk wrote the history of the Holocaust in Mizoch, which I edited and contributed a co-authored chapter to.

This research has led to a substantial number of micro-discoveries that merit attention and further study. Given the semi-academic nature of these publications, some interesting findings could not be included, so they are worth highlighting here. Thus, this article seeks to supplement the conclusions and single out the key findings of the series.

Historiographic importance of the series

One question that the volumes in The Life and Death of Jewish Communities do not address is the historiographic importance of this series. The editors and I decided not to include an overview of the historiographic discussions so as not to burden readers with the details of these academic discussions. [2]

I will explain why this text deals with western Volyn. Then, I identify who is studying the history of the Holocaust in this region. In Ukrainian academic practice, the political and administrative order that exists within the chronological framework of a given study is often used to establish the geographic framework. For example, in the case of the Nazi occupation and the Holocaust, this is the General District of Volyn-Podillia. Other scholars study the history of the Holocaust in current administrative-territorial divisions (for example, my colleague Roman Mykhalchuk's dissertation examines the Holocaust in Rivne Oblast). [3]

However, neither of these approaches is entirely optimal. The history of the Holocaust is not just about mass killings during the Second World War. In order to understand the social dynamics, that is, the set of complex factors that affected interethnic relations during the war and the genocide, one cannot overlook the prewar history of Jewish communities. This history merits at least brief elucidation because the situation that Jewish communities found themselves in was affected not only by the Nazis' genocidal policies but also by the sociocultural, economic, and political features of interethnic relations that were formed before the Second World War. The following important factors affected Jews' chances of survival and often determined their survival strategies during the Holocaust: the prewar level of antisemitism; interethnic relations (points of contact; interaction and conflicts with non-Jewish communities, e.g., Ukrainians, Poles, Czechs, Germans, and others); the level of assimilation among Jews or their knowledge of the languages, traditions, and customs of the surrounding non-Jewish communities, which somewhat improved the chances of survival in the conditions of an ethnic borderland [4]; experience in political engagement and participation during the interwar period, which proved advantageous for choosing survival strategies during the Second World War and the Holocaust; the level of cohesion within Jewish communities; and the character of the ruling political regime as one that directly and indirectly influenced the formation of certain institutionally conditioned behavioral patterns within Jewish and Gentile communities. [5]

These factors can be studied if one disallows the geographical boundaries that had formed a separate historical, cultural, and political-administrative space during the interwar period. Thus, by western Volyn, I mean the majority of the territory that was part of Poland's Wołyń Voivodeship during this period. This political-administrative factor is considered decisive because it affected all other cultural and economic processes in this territory, which, in addition to Volyn, included other Ukrainian regions, such as Polissia.

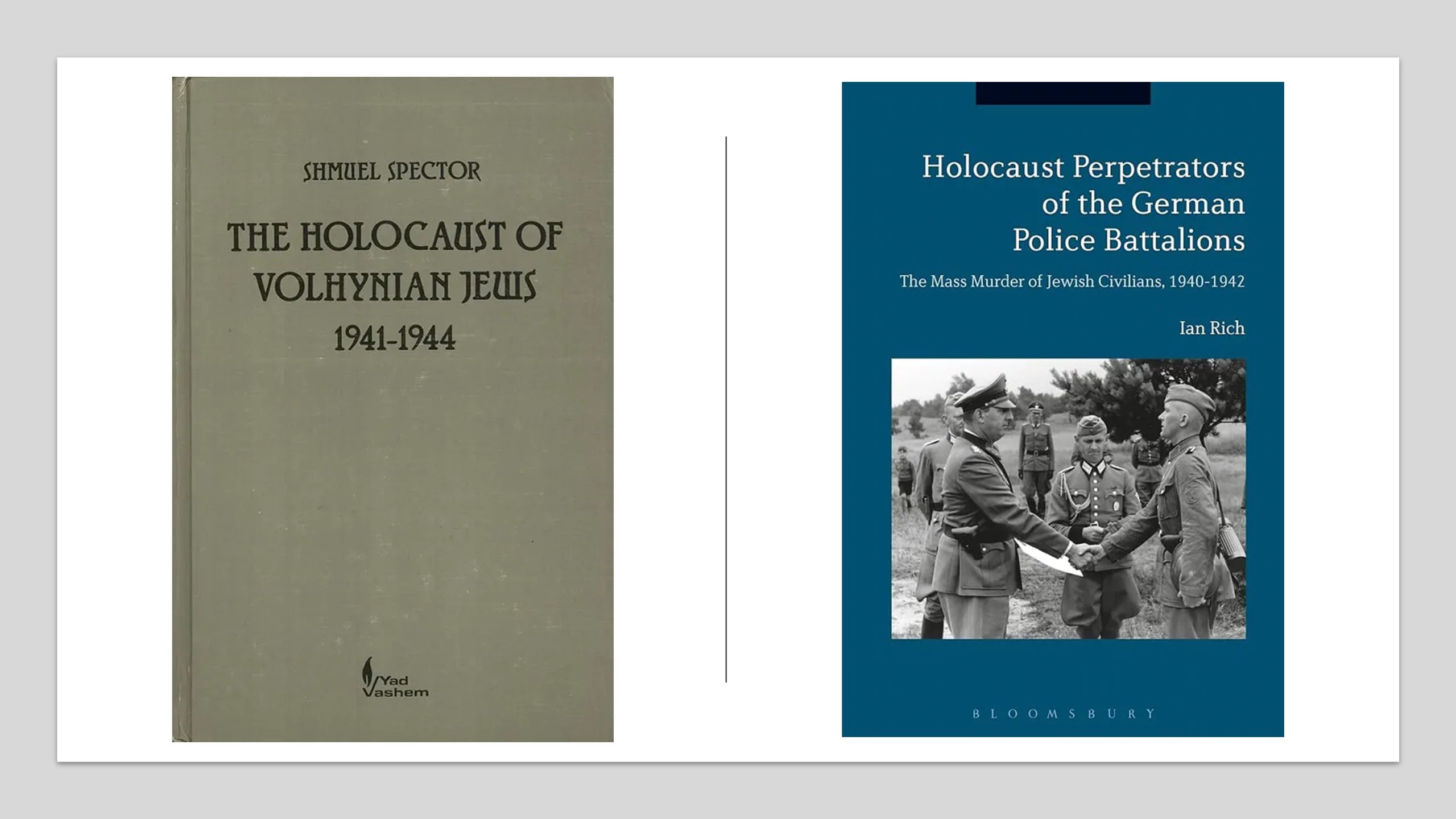

In the 1970s, the distinguished Israeli historian Yehuda Bauer raised questions about interethnic relations in interwar Poland and the behavior of neighbors during the Holocaust. [6] However, the first scholar to study the history of the Holocaust in the geographical context of Volyn was Shmuel Spector. [7] His monograph on the history of the Holocaust in that region is the most systematic to date. The author consulted a wide range of sources, from German documents to recollections and eyewitness testimonies. This enabled him to recreate the basic contexts of the Holocaust in Volyn in great detail: interethnic relations during the interwar period in Poland; political, economic, and cultural changes during the establishment of Soviet rule in the region (1939–1941); combat operations at the beginning of the German-Soviet war and the Nazi occupation of Volyn; the pogroms in Volyn; the main stages of the Holocaust organized by the military administration; the stages of ghettoization; the second wave of violence and cycles of the liquidation of the Volynian ghettos; survival strategies and forms of Jewish resistance; and the attitude of Soviet partisan formations toward surviving Jews hiding in forested areas and receiving assistance (or not) from the local population.

Despite the comprehensive and systematic nature of Spector's research, his study was published in 1990, when there was no proper access either to archives in Ukraine or to the largest database of testimonies of Jewish survivors (the USC Shoah Foundation Visual History Archive was created only in the mid-1990s). Moreover, Spector lacked access to sources that would have comprehensively recreated the perspective of the largest non-Jewish ethnic group, that is, a broad range of Ukrainian peasants who were not involved in the formation and activities of the Nazi occupation authorities or partisan movements. In the bargain, the modern methodology of Holocaust studies, particularly those that analyzed the behavior of local populations, Jewish survival strategies, and an understanding of genocide dynamics, was still in the developmental stage at the time.

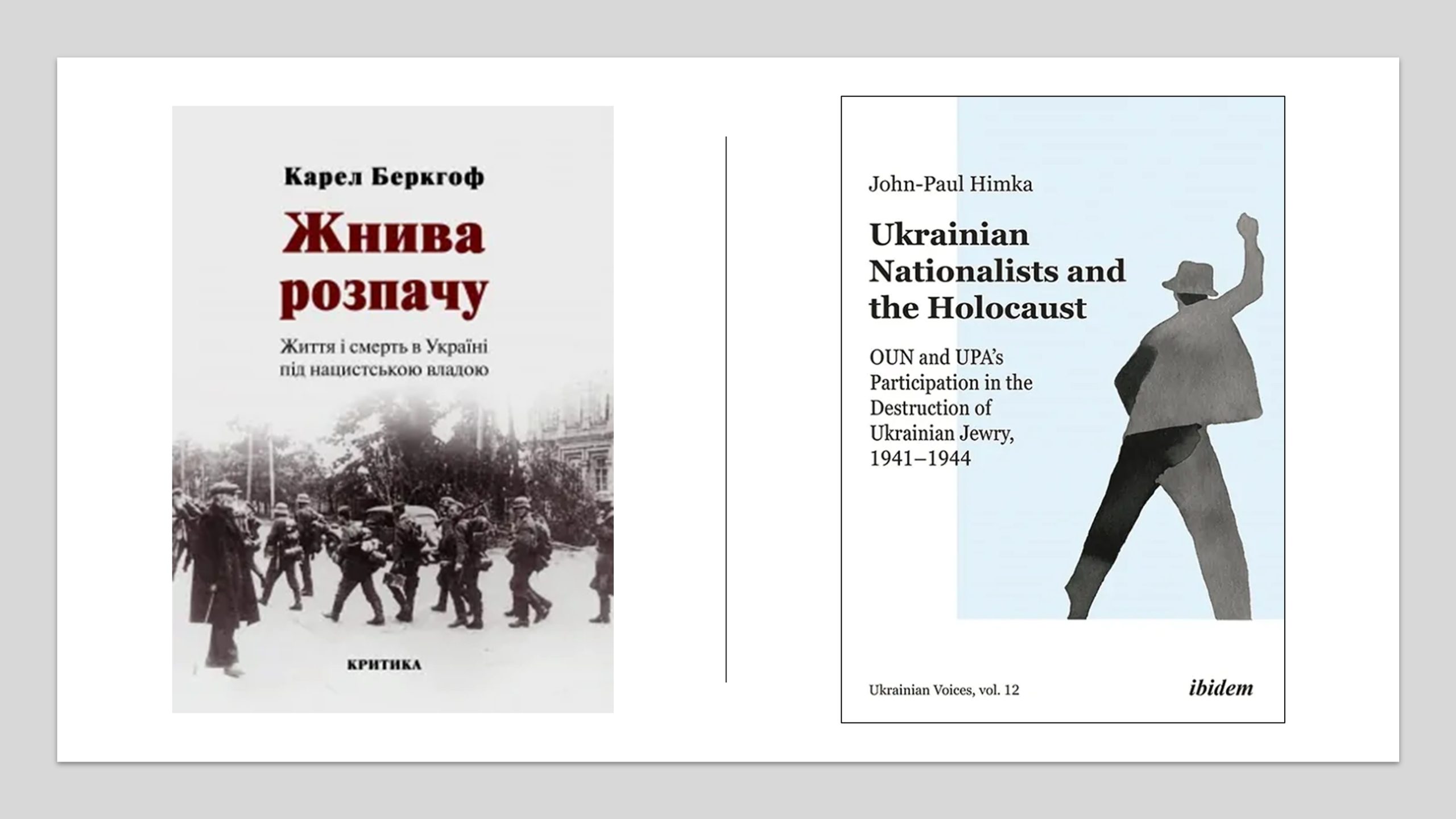

However, most of the studies that appeared after Spector's book was published provided details about various aspects of the Holocaust, for example, the formation of the police apparatus [8] or the role of individual partisan movements in the killing/rescuing of Jews. [9] Some were more thorough explorations of the microhistory of crimes committed in specific populated areas of western Volyn. [10] In one of his earliest books, Sketches from a Secret War, the American historian Timothy Snyder focused on interethnic relations and ethnic policy in the Wołyń Voivodeship during the interwar period. [11] In his article entitled "The Life and Death of Jewry in Western Volhynia, 1921–1945," Snyder describes the fate of Volynian Jews during the Holocaust. [12] His pivotal monograph on the history of the Holocaust, Black Earth: The Holocaust as History and Warning, focuses on the survival strategies of western Volynian Jews during the Holocaust. [13] Several recent publications on the history of the Holocaust in Ukraine explore western Volynian topics in a comparative context by looking at other regions of occupied Ukraine. Foremost among them are Karel Berkhoff's Harvest of Despair: Life and Death in Ukraine under Nazi Rule [14] (the author examines anti-Jewish violence in western Volyn in the summer of 1941 and compares the Nazi occupation policy in Volyn with other regions in Reichskommissariat Ukraine) and Kai Struve's Deutsche Herrschaft, ukrainischer Nationalismus, antijüdische Gewalt: Der Sommer 1941 in der Westukraine (in his conclusions, the author compares the "pogroms" in Eastern Galicia with manifestations of anti-Jewish violence in western Volyn). [15]

Also worth mentioning are the studies published by the American historian Jared McBride. His series of academic microhistories shed light on the dynamics behind the destruction of Jewish and other communities in Volyn during the Nazi occupation. [16] His doctoral dissertation, "'A Sea of Blood and Tears': Ethnic Diversity and Mass Violence in Nazi-Occupied Volhynia, Ukraine, 1941–1944" [17], is an innovative and systematic attempt to recapitulate the social history of interethnic violence in Volyn during the Nazi occupation. The author is focused on the Holocaust as well as on such insufficiently studied questions as the Ukrainian-Polish conflict, the role of the auxiliary police and local residents in the killings of their neighbors, the role of partisan movements in interethnic violence, and other topics. One can only regret that this dissertation was not published as a monograph. Also worthy of mention is Martin Dean's recent article about forced labor camps for Jews in Reichskommissariat Ukraine. [18] The article includes a list of most of the camps located on the territory of western Volyn, as well as data on their creation and functional features — questions that have not received proper attention until now.

The Ukrainian historian Andriy Usach has played a significant role in researching the Ukrainian perspective on the Holocaust in western Volyn. He was the regional coordinator of the Voices oral history project. Recently, in collaboration with Anna Yatsenko, he recorded the testimonies of Ukrainians about the Second World War in Volyn for the archive of the civic organization After Silence. He summarized the results of his oral-history activities in the article "'They Were Not Germans…': Local Perpetrators of the Holocaust in Non-Jewish Oral History Testimonies." [19] The article discusses the characteristics of Ukrainian peasants' recollections about local perpetrators of the Holocaust in Volyn.

Ian Rich highlights an important aspect of how the Holocaust unfolded in western Volyn from the perspective of German perpetrators. [20] He analyzes heretofore little-known facts about the activities of German police battalions in occupied Ukraine. One chapter of his monograph explores the way German police units in 1941 evolved from killing mostly Jewish men to shooting all Jews. This development began with their crimes in western Volynian villages. A vital role in this was played by younger officers, who had completed ideological training during their studies and demonstrated considerable enthusiasm for implementing the Nazi racial policy of genocide.

Finally, the encyclopedic publications of the Ukrainian trailblazer Alexander Kruglov [21] and his colleagues, Andrej Umansky and Ihor Shchupak, as well as the comprehensive publication The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933–1945, comprise the most comprehensive narrative base of facts, dates, and events pertaining to the Holocaust in populated areas of western Volyn. Kruglov and Dean contributed a substantial number of articles to the USHMM encyclopedia. [22]

Main groups of research sources

Despite the existence of the above-mentioned research, microhistories of the Holocaust in the towns of Volyn are leading to many minor discoveries that deepen our understanding of the dynamics of genocide. This has happened thanks to the use of new sources, first and foremost, Soviet criminal cases that were opened against auxiliary police officers and local authorities (municipal and raion administrations under Nazi occupation), which are held in the archives of the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU). Although many researchers have already been able to work with these types of sources, they are still insufficiently researched. It is precisely criminal cases that shed light on how the local occupation apparatus was organized: who served in the auxiliary police; what their motives were; how was the structure of this apparatus organized on the grassroots level in small towns and villages; the functional roles of local government bodies (municipal and raion administrations as well as village elders and their deputies); and what these governing bodies had to do with the implementation of the Holocaust.

An important role is also played by the perspective of Ukrainian eyewitnesses, now available thanks to such oral history projects as Voices, run by the Babyn Yar Holocaust Memorial Center [23], the civic organization After Silence [24], the archive of Yahad-In Unum (since these archives are not readily accessible, these sources were used to a lesser degree during the writing of the series of publications), and the audio recordings made by my colleagues at the Ukrainian Center for Holocaust Studies. [25] Created in the form of open, narrative interviews, these recollections of local residents provide perhaps the best understanding of the Holocaust from the perspective of Ukrainian peasants, who until now have been insufficiently represented in Holocaust studies.

More classic sources are no less important: the testimonies held in the USC Shoah Foundation Visual History Archive; archival collections of Yad Vashem in Jerusalem; the archive of the Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw; and, of course, the series of so-called Yizkor memorial books [26] written by Jewish Holocaust survivors who settled in Israel after the war. During my research, I examined documents stored in the State Archive of Volyn Oblast (DAVO) and the State Archive of Rivne Oblast (DARO). It is interesting that a comparison of various groups of sources — archival documents of the Nazi occupation authorities, Soviet investigations of Nazi crimes in the occupied territories, ego-documents, and eyewitness testimonies — produced a substantial number of unanticipated results.

Working on these publications reinforced my conviction that an archival document can lead to erroneous treatments no less than oral history testimonies. For example, during the writing of Ostrozhets: Life and Death of the Jewish Community, I located an archival document about the deportation of Jews to the Ostrozhets ghetto. [27] According to the information contained in this document, the transportation of Jews from surrounding villages to the Ostrozhets ghetto was supposed to have taken place by 30 June 1942. Since this document is dated 22 June 1942, one may conclude that the Jews of Torhovytsia and other villages were transported to the Ostrozhets ghetto sometime that month, i.e., after this document appeared. However, at least three eyewitnesses say otherwise, claiming that they were deported to the ghetto in May 1942. If Jan Gross's fundamentally affirmative method [28] is applied to eyewitness testimonies, they should be considered as equivalent to an archival document. In this case, the dates marked in the document can easily lead to incorrect conclusions because they contradict three other sources. The cumbersome Nazi bureaucratic machine was sometimes inclined to issue orders after the fact. For example, a considerable number of directives about anti-Jewish restrictions were promulgated in a number of populated areas only in late 1942 and 1943. By that time, most Jews had been killed. Be that as it may, documents can misinform us without eyewitness testimonies and lead to faulty conclusions about the chronology of events.

Oral history testimonies and ego-documents

Thanks to the work done by the Connecting Memory project, I was able to gain access to a broad selection of oral Holocaust testimonies from the USC Shoah Foundation Visual History Archive during my research. These testimonies are not always accessible to researchers because they were produced in the languages of the countries where surviving Jews had immigrated after the Second World War. The testimonies are in Portuguese, Spanish, Hebrew, Yiddish, German, French, and English, to name a few, and it is the rare researcher who can understand all these languages; most certainly cannot. Most of the Connecting Memory project video recordings pertaining to the populated areas covered by the project's research were transcribed in the original language and translated into Ukrainian; this significantly expanded the source base. The interviews done by the Shoah Foundation are among the few available sources on the local history of small towns and are thus especially valuable. The few extant photographs from the prewar period provide important insight into the fate of specific individuals and mark the return from oblivion of the faces and names of murdered Jews.

Naturally, working with testimonies and ego-documents necessitates special approaches to recreating Holocaust events in western Volyn. Some positivist historians hold the arrogant view that eyewitness testimonies are a significantly less reliable source for research. This opinion is most often held by positivists who believe in the possibility of achieving some kind of "objective truth of the past" — "historical truth," as it is often expressed. Indeed, the accounts of narrators who talk about the past are subjective. However, if we acknowledge that history is a science without objective laws and correct truths, this aspect of eyewitness testimonies and ego-documents becomes an advantage rather than a flaw. These types of sources help researchers gain a significantly better understanding of the perspectives of various groups — Jews, Ukrainians, Poles, Czechs, and others — on the events that took place during the Nazi occupation.

At the same time, acknowledging the subjectivity of various perspectives on the past is not grounds for rejecting attempts to approach the truth, as Edmund Husserl wrote. [29] When researchers work with eyewitness testimonies, it is not enough to carry out a classic "critical analysis of sources" in its positivist understanding (which, under certain circumstances, is also necessary but not crucial). This type of source features aspects that are not worth examining in the context of the popular "truth — falsehood" dichotomy (or "fake," a popular notion today, often mistakenly attributed to things that belong to the sphere of interpretations and assessments from the standpoint of various value systems or group perspectives, rather than cold, hard facts, and therefore not to be treated either as truths or untruths). Reflecting on why various eyewitnesses remember events one way rather than another is an approach that allows the researcher to correct the work of his consciousness on interpreting the past through the prism of this group of sources.

Testimonies provided by various groups of eyewitnesses (Ukrainians, Jews, Poles, and Czechs) enable the reader or researcher to see how the perspectives on the same events can differ. For example, Jewish eyewitnesses talk more often about local perpetrators, such as auxiliary police officers, than about Germans, who were the main organizers of the genocide. There are several explanations for this. For one thing, Jews were better acquainted with local perpetrators than with the Germans. Narrators had a better recollection of Germans who lived permanently in raion centers, but these were usually small gendarme posts numbering no more than three people.

Furthermore, Jewish residents did not see the members of killing squads every day and could not know them by sight or name. For the majority of Jews, these people were the anonymous faces of evil, and encounters with them were fatal, as a rule. In this regard, Gross writes: "All that we know about the Holocaust — by virtue of the fact that it has been told — is not a representative sample of the Jewish fate suffered under Nazi rule. It is all skewed evidence, biased in one direction: these are all stories with a happy ending." [30] The factor of "skewed evidence" can certainly be one of the reasons why surviving Jews so often recall local perpetrators and so rarely remember Germans, who were the root cause of their sufferings. An encounter with German death squads was fatal. Many Jews from western Volyn who survived are those who escaped from the ghetto before being shot. They did not face the muzzle of a German machine gun and might never have seen the faces of these killers. They have significantly better recall of the final chronological segment of their sufferings: their wretched sojourn in surrounding forests and flight from the "hunters" — auxiliary police officers recruited from among local peasants. It is these latter groups of locals that played a key role in the final stage of the "hunt" for Jews after the liquidation of the ghetto. [31]

In analyzing the accounts of Ukrainian eyewitnesses, a researcher must consider the factor of self-censorship. For example, a considerable number of Ukrainian narrators state that the members of the auxiliary police were Poles or Ukrainians from other populated areas (in other words, "strangers" in the context of self-identification with a national or local community). Meanwhile, in Jewish accounts, we often hear information indicating that, at least in the summer of 1941, these were locals, mostly Ukrainian peasants. Since most of the Ukrainian narrators are part of the communities that they talk about in their memories of the war, it is more difficult for them to speak about this complex and traumatic history. A connection with a local community necessitates a certain level of loyalty and conformity, which is not always binding on Jewish narrators who long ago left Ukraine or the towns where they had survived the Holocaust and then linked their lives with other states or communities.

On the other hand, studies have shown that if Jews remained part of a certain community or nation after the war, this imprint of conformity and a better attitude toward their neighbors was sometimes layered onto their memories. [32] It is difficult to research this aspect using the example of western Volyn because the absolute majority of the few Jews who survived the war decided to immigrate. Those individuals who remained moved to other cities. Thus, self-censorship in their testimonies may not even be traceable.

In working with testimonies, researchers must understand the process behind their formation and the key factors that could have influenced people's recollections. However, it is possible to track such dynamics only if certain memories were registered several times during chronologically different periods. We can study such aspects only through the example of Jewish memories because the Ukrainian perspective has only recently become the subject of oral history projects.

One recollection of the Holocaust that was registered twice is that of Pola Grinstein. Her testimonies were recorded, the first time in writing, for an archival collection in Tel Aviv in 1961 [33] and the second time in 1994, in the form of videotaped testimony for the USC Shoah Foundation Visual History Archive. [34] Whereas the recollections recorded by Yad Vashem are a summary on paper of the narrator's factual information, her videotaped testimony is distinguished by its higher level of emotion and depth. In the latter, Grinstein recalls a larger number of people and describes them in greater detail [35], once again proving that human memory is an immense "archival" receptacle in which some parts can be actualized depending on contexts, the specificity of the flow of memories and questions posed by the interviewer during the process of interacting with the texture of the narrator's memory. This points to the value of oral history compared to the memoirist exposition of a narrative in which an eyewitness does not always recall everything or frames the recollections in literary garb with all attendant consequences.

However, one of the most fascinating examples of the institutionalization of memories of the past through interaction with the changing reality of contemporary life is the recollections and testimony of Sonya Papper (née Sara Kulisz). They were recorded three times, allowing researchers to compare the earlier versions with the later ones and to track the evolution and formation of a complete narrative. The earliest written version of her recollections dates to the 1940s and is held at the Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw, filed under the name of Sara Kulisz. [36] It was recorded during her sojourn in Lodz around the mid-1940s. Her later recollections were recorded by the Visual History Archive in 1994. The last version was published in 1996 in book format and entitled Sonya's Odyssey. [37] There is a clear difference between Papper's first and later versions. The first version is based on her diary. According to Papper, she wrote it while she was hiding in the woods near Dubno and Ostrozhets. The entries are short, episodic, intermittent, and inconsistent. At the same time, they are plausible because they are based on Papper's recent memories and diary entries, reflecting her freshest memories. These memories are marked by unresolved trauma and the chaotic nature of the terrible events that happened to Papper, which she had not yet fully absorbed. Her very first recollections thus consist of confusing and fragmentary accounts.

The last version of her recollections, Sonya's Odyssey, is a literary and fairly complete and clearly structured narrative about surviving the Holocaust, written when the world knew perfectly well what the Holocaust was and how it was organized. The Visual History Archive recorded Papper's testimony in 1994, after which she wrote the most systematic narrative of her story. With every new exposition of the past, there is greater order and consistency in the presentation of narrators' memories. Experts of the Fortunoff Video Archive noted this pattern. [38]

The three versions of Papper's recollections are supplemented by interesting stories. For example, in the testimony given to the Visual History Archive, Papper talks about her life in emigration, whereas her earliest written testimony did not contain this information. Her first postwar testimony features a story about the death of one of her rescuers, a Ukrainian man named Serhii, supposedly killed by "Bulba's followers" right after the war. [39] The videotaped testimony omits this detail. In her first recollections, Papper also recounts that an elderly Ukrainian couple helped her, but in the later versions, she calls them Czechs. By the 1990s, communities of Jewish survivors had established a narrative of the Holocaust, in keeping with which ethnic Ukrainians did not appear in the best light — far from it. This factor may have been layered onto Papper's presentation of the past, leading her to exclude those Ukrainian rescuers from her narrative by calling them Czechs. In the last version of her recollections, Papper frequently mentions Czechs and Poles as rescuers. This does not appear in her first testimony focused more on Ukrainian neighbors, some of whom helped, while others betrayed her during the Nazi occupation.

For a better understanding of this point, let us look at Papper's recollections of the first weeks of the Nazi occupation of Ostrozhets and surrounding villages in the summer of 1941. Papper says that possibly in July 1941, local peasants (and perhaps police officers as well, but she only mentions "five Ukrainians") took part in the anti-Jewish violence in Malyn, a village near Ostrozhets, as well as in surrounding villages. Her brother-in-law and another local Jew were killed. There are interesting discrepancies between Papper's last two versions (recorded in the 1990s) of these events and the first one (dating to the 1940s).

In the last version, Papper recounts that she learned of her brother-in-law's death from a Ukrainian acquaintance who had apparently taken part in this violence: "We understood that he had taken part in the violent death of my brother-in-law" (the first version does not include this detail). [40] In the 1990s version, she describes her arrival in Malyn to search for the body of her murdered brother-in-law: "My sister and I decided to look [for the body — P.D.], and went to Malyn. But we did not find the body there. Then we went to the house of a local Gentile, hoping to find out something from him. A woman met us at the door and said: 'Why have you come to ask about the shochet? Ask your own Jews — they killed him!'" [41]

Below is the first version of Papper's account of these events, which was based on her diary entries recorded in the 1940s, right after the war:

"Arriving in the village, we headed to the place that a local Gentile pointed out to us, but we did not find anything there. Then, I mentioned that there was a Jew living on the outskirts of the village. I said, 'Sister, let's go to that Jew. He will show us the exact place.'

We entered his house and asked him, but he played dumb and said that he didn't know anything. When we left his house, we met another Gentile acquaintance. He asked me what I was doing here. I told him we had come to cover the body [sic] of our killed husband and brother-in-law and asked:

'Maybe you know something about this, Stepan? Tell the whole truth. Show us where his body is.'

'Why should I tell you when the Jew knows better? He was the one who pushed him into the river; let him tell you,' he replied and went off. Shouting and full of despair, we ran back to the Jew. His face turned dark as night, and in a dejected tone of voice, he recounted the following…" [42]

Thus, in this first version, Papper describes the traumatic event in greater detail and more problematically in her assessment of the role of local peasants. In this initial version, she also recounts how Ukrainian assailants forced another Jewish resident of the village of Malyn to push Papper's brother-in-law into the river. He did this because he had received threats. [43] The second version only states that this Malyn resident was forced to beat Papper's brother-in-law with a stick, but he refused and was beaten by the Ukrainian attackers, after which he played dead. [44]

In both accounts, the narrator recounts in somewhat different ways the most traumatic story of the killings of her two children. [45] In the first postwar version, dating to the second half of the 1940s, Papper recalls that she witnessed the killing of her entire group that was hiding in the woods shortly after the liquidation of the ghetto in Ostrozhets. They were killed near the hiding place where they were discovered. However, the lives of her children were supposedly spared; the assailants took them away. Papper accidentally exited the hideout right on the eve of an unexpected roundup and hid in nearby bushes, where she observed everything that took place.

In the later narrative in the 1990s, this account is missing, and Papper recounts that she was in the village searching for food during the roundup. In this second version, Papper's children were killed near the hiding place, together with all the other members of the surviving group (that is, the attackers did not detain or take them away).

This may be a case where the story becomes complete by analyzing all the fragments of memories and filtering out various layers that help conceal a harrowing and shocking truth. The woman was able to see her children being killed, but she did not dare leave her hiding place because she knew she could not help them and that she, too, would be killed. Our societies know and love stories about women's self-sacrifice. We often tend to present stories of survival in the black-and-white tones of good confronting evil. But the reality is always much more contradictory and complex. The experience of genocide often demonstrates nothing heroic or educational. It leaves a terrible trauma in which it is difficult to discover any moral lessons for today.

This story demonstrates that eyewitness memories constitute a narrative that, over time, is framed in certain raiments under the influence of interactions with contemporary life. The factors that influence their formation include the specific features of collective memory, the politics of memory, personal trauma, its (non)comprehension, and other factors. Reality in memories is never a static phenomenon; it constantly evolves and changes — something researchers should take into consideration.

The photographs used in this article are from open sources and the archive of the Connecting Memory Project.

Endnotes

1 This series was recently expanded by the publication of volumes about the Holocaust in populated areas outside of western Volyn. However, the present article surveys research on western Volynian towns, the lion's share of which was written by this author. All the volumes in this publication series are available on the website of the Ukrainian Center for Holocaust Studies. The author owes a debt of gratitude to the Ukrainian historian Andriy Usach and the German historian Svetlana Burmistr for their editorial assistance and valuable input, which helped improve this text.

2 An exception to the rule, only one article in this series entitled "Holoby i Mel′nytsia: Zhyttia ta zahybel′ ievreis′kykh hromad" includes an afterword that briefly describes the sources and earlier research on this question.

3 R. Iu. Mykhal′chuk, Smert′ і vyzhyvannia pid chas Holokostu: Tereny suchasnoї Rivnenshchyny; Monohrafiia (Rivne: Volyns′ki oberehy, 2022).

4 The term "ethnic borderland" refers to the multiethnic world that existed in western Volyn until the Second World War.

5 Many researchers, especially Evgeny Finkel, have stressed the importance of these factors. For detailed discussion, see Evgeny Finkel, Ordinary Jews: Choice and Survival during the Holocaust (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2017), pp. 4–46.

6 Yehuda Bauer, The Holocaust in Historical Perspective (Canberra: Australian National University Press, 1978), pp. 56, 59.

7 Shmuel Spector, The Holocaust of Volhynian Jews, 1941–1944 (Jerusalem: Yad Vashem, Federation of Volhynian Jews, 1990).

8 Martin Dean, Collaboration in the Holocaust: Crimes of the Local Police in Belorussia and Ukraine, 1941–1944 (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2000). Similar to other publications, this work does not offer many details about the organization of police units on the local level in western Volynian cities and towns. It covers a broader geographic area, including the territories of Belarus, paying little attention to western Volyn. Nevertheless, owing to the innovative nature of Dean's research, many of his findings are still relevant.

9 A key study on the role of the OUN and the UPA in the killings of Volynian Jews is John-Paul Himka, Ukrainian Nationalists and the Holocaust: OUN and UPA's Participation in the Destruction of Ukrainian Jewry, 1941–1944 (Stuttgart: Ibidem-Verlag, 2021).

10 For example, Yehuda Bauer, "Sarny and Rokitno in the Holocaust: A Case Study of Two Townships in Wolyn (Volhynia)," in The Shtetl: New Evaluations, ed. Steven T. Katz (New York: New York University Press, 2006), pp. 253–89; Dzh. Berdz [Jonathan Burds], Holokost u Rivnomu: Masove vbyvstvo v Sosonkakh, lystopad 1941 r., trans. D. Aladko (Rivne: Volyns′ki oberehy, 2017 (first appeared in English in 2013); Maksym Gon, Rowne: Obrysy znykloho mista (Rivne: Volyns′ski oberehy, 2018); I. Kapas′, “Getto u Dubrovytsi za materialamy arkhivno-kryminal′noї spravy Khaїma Sygala,” Holokost і suchasnist′: Studiї v Ukraїni і sviti 11, no. 1 (12012); Bohdan Zek, “Holokost v okupovanomu Luts′ku u 1941–1942 rr.,” Holokost і suchasnist′: Studiї v Ukraїni і sviti 13, no. 1 (2015) (a series of articles by Roman Mykhalchuk).

11 Timoti Snaider [Timothy Snyder], Narysy taiemnoї viiny: Pol′s′kyi khudozhnyk na sluzhbi vyzvolennia Radians′koї Ukraїny (Kyiv: ТАО, 2023).

12 Timoti Snaider, “Zhyttia і smert′ zakhidnovolyns′kykh ievreїv, 1921–1945 rr.,” in Shoa v Ukraїni: Istoriia, svidchennia, uvichnennia (Kyiv: DUKH I LITERA, 2015), pp. 113–62.

13 Timoti Snaider, Chorna zemlia: Holokost iak istoriia і zasterezhennia (Kyiv: Meduza, 2017).

14 Karel Berkhof [Karel C. Berkhoff], Zhnyva rozpachu: Zhyttia і smert′ v Ukraїni pid natsysts′koiu vladoiu (Kyiv: Krytyka, 2011).

15 Kai Struve, Nimets′ka vlada, ukraїns′kyi natsionalizm, nasyl′stvo proty ievreїv: Lito 1941 roku v Zakhidnii Ukraїni (Kyiv: DUKH І LITERA, 2022).

16 Jared McBride, "The Many Lives and Afterlives of Khaim Sygal: Borderland Identities and Violence in Wartime Ukraine," Journal of Genocide Research 23, no. 4 (2021), Special issue on Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union. Published online on 28 March 2021; idem, "The Tuchyn Pogrom: The Names and Faces Behind the Violence, Summer 1941," Holocaust and Genocide Studies 36, no. 3 (Winter 2022): 1–19; idem, Contesting the Malyn Massacre: The Legacy of Inter-Ethnic Violence and the Second World War in Eastern Europe, The Carl Beck Papers in Russian and East European Studies, no. 2405 (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh, 2016).

17 Jared Graham McBride, "'A Sea of Blood and Tears': Ethnic Diversity and Mass Violence in Nazi-Occupied Volhynia, Ukraine, 1941–1944" (PhD diss., University of California, 2014).

18 Martin Christopher Dean, "Forced Labor Camps for Jews in Reichskommissariat Ukraine: The Exploitation of Jewish Labor within the Holocaust in the East," Eastern European Holocaust Studies, https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/eehs-2022-0002/html

19 “‘To ne nimtsi…’: Mistsevi vynuvattsi Holokostu v neievreis′kykh usnoistorychnykh svidchenniakh,” in Slukhaty, chuty, rozumity: Usna istoriia Ukraїny ХХ–ХХІ stolit′; zb[irnyk] nauk[ovykh] prats′, ed. G. Grinchenko (Kyiv: ART KNYHA, 2021), pp. 143–62.

20 Ian Rich, Holocaust Perpetrators of the German Police Battalions: The Mass Murder of Jewish Civilians, 1940–1942 (London, New York, Oxford, New Delhi, Sydney: Bloomsbury Academic, 2018).

21 See, for example, A. Kruglov, A. Umanskii [Umansky], and I. Shchupak, Kholokost v Ukraine: Reikhskomissariat "Ukraina," Gubernatorstvo "Transnistriia"; monografiia (Dnipro: Tkuma Ukrainian Institute for Holocaust Studies and ChP "Lira LTD," 2016); A. I. Kruglov, Entsiklopediia Kholokosta: Evreiskaia entsiklopediia Ukrainy, ed. I. M. Levitas (Kyiv, 2000).

22 The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933–1945, vol. 2, pt. B., ed. Martin Dean (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2012).

23 For detailed discussion of the importance of these testimonies in studies on the Holocaust in western Volyn, see Petro Dolhanov. "'Everyone Had to Do With It, Either through Family or Some Other Means': Testimonies of Ukrainian Witnesses about the Holocaust in Volhynia," EHRI Document Blog, https://www.ehri-project.eu/new-ehri-document-blogpost-testimonies-ukrainian-witnesses-about-holocaust-volhynia; idem, "'Inshyi/Chuzhyi': Obraz ievreїv u spohadakh ukraїns′kykh susidiv pro Druhu svitovu viinu," in Problemy istoriї Holokostu: Ukraїns′kyi vymir 14 (December 2022): 41–57.

24 The civic organization After Silence is currently uploading its archive of videotaped testimonies. Andriy Usach and Anna Yatsenko travel throughout Ukraine videotaping recollections of the Second World War and the policies of the Nazi and Soviet totalitarian regimes. They graciously offered me access to some video recordings that pertain to the Holocaust in western Volyn.

25 The Ukrainian Center for Holocaust Studies has been a key long-time partner of the projects Protecting Memory and Connecting Memory. In researching mass killing sites in Ukraine with the aim of installing commemorative markers there, the staff of the center often had occasion to record the oral testimonies of residents who remembered the Nazi occupation. The recordings were done according to narrative-interview methods.

26 Most of these testimonies were written in Hebrew. Many have been translated into English and are posted on the website JewishGen.

27 Petro Dolhanov, Ostrozhets′: Zhyttia ta zahybel′ ievreis′koï hromady (Kyiv: Ukraїns′kyi tsentr vyvchennia istoriї Holokostu, 2023).

28 Jan T. Gross, Neighbors: The Destruction of the Jewish Community in Jedwabne, Poland (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2022). Gross concludes: When considering survivors' testimonies, we would be well advised to change the starting premise in appraisal of their evidentiary contribution from a priori critical to in principle affirmative. By accepting what we read in a particular account as fact until we find persuasive arguments to the contrary, we would avoid more mistakes than we are likely to commit by adopting the opposite approach, which calls for cautious skepticism toward any testimony until an independent confirmation of its content has been found" (pp. 139–40).

29 As Edmund Husserl noted, if science — as it must eventually admit — does not de facto attain the realization of a system of absolute truths and is forced constantly to modify its truths, then it still follows the idea of absolute or scientific real truth and therefore gets used to living in an infinite horizon of approaches that strive for this idea. Therefore, the unattainability of an objective understanding of the past does not yet free researchers from the task of trying to get as close to it as possible. See E. Huserl′, Kartezians′ki medytatsiї: Vstup do fenomenolohiї (Kyiv: Tempora, 2021), p. 65.

30 Gross, Neighbors, p. 141.

31 Studies in behavioral psychology have shown that a person recalling the past relies most on the last fragment of their memories of a certain event. For detailed discussion, see Daniel′ Kaneman [Daniel Kahneman], Myslennia shvydke і povil′ne (Kyiv: Nash format, 2022).

32 For example, Katerina Kralova's research on the memories of surviving Greek Jews reveals that Jews who left Greece after the war talked about the involvement of Greek communities in the Holocaust much more openly than those who remained and decided to integrate into the Greek national community during the postwar period. For detailed discussion. See her article, "Being a Holocaust Survivor in Greece: Narratives of the Post-War Period, 1944–1953," in Giorgos Antoniou and A. Dirk Moses, eds., The Holocaust in Greece (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018), pp. 304–26.

33 Testimony of Pola Grinstein (in Hebrew), Yad Vashem Archives, collection O.3, file 1775.

34 Pola Grinstein, Interview 21494. Visual History Archive, USC Shoah Foundation Institute, 4 parts.

35 Pola Grinstein, Interview 21494, pt 1.

36 Testimony of Sara Kulisz (in Yiddish), Archive of the Żydowski Instytut Historyczny (AZIH) in Poland, 302/52.

37 Sonya Papper, Sonya's Odyssey, trans. Morris Nimovitz and Joshua W. Shapiro (Los Angeles: Shapmor Press, 1996).

38 For detailed discussion, see Noah Shenker, Reframing Holocaust Testimony (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2015), p. 43.

39 The local population called the fighters of the Polissian Sich, led by Taras Bulba-Borovets, "Bulbivtsi." However, it is likely that in 1944, the year that figures in these testimonies, this name was used in some populated areas to denote UPA fighters.

40 Papper, Sonya's Odyssey, p. 27.

41 Ibid.

42 Testimony of Sara Kulisz, 302/52 (9). "To drown someone in a river" was a widespread instrument of anti-Jewish violence used by the local population in the summer of 1941. Andriy Usach offers an example of this practice in the town of Smotrych. He theorizes that such violent acts targeting Jews could have been dictated by certain antisemitic stereotypes, possibly connected with the idea that Jews did not know how to swim. This hypothesis requires verification through anthropological studies of antisemitic stereotypes. For detailed discussion, see Andriy Usach, “‘Skhidna aktsiia” OUN(b) ta antyievreis′ke nasyl′stvo vlitku 1941 r.: Vypadok Smotrycha і Kupyna,” https://uamoderna.com/pdl-min/sxidna-akcziya-oun-b-ta-antievrejske-nasilstvo-vlitku-1941-r-vipadok-smotricha-i-kupina/.

43 Testimony of Sara Kulisz, p. 10.

44 Papper, Sonya's Odyssey, p. 28

45 For detailed discussion, see Dolhanov, Ostrozhets′, pp. 45–46.

Petro Dolhanov is a Candidate of Historical Sciences, Assistant Professor of Pedagogy and Educational Innovations at the Rivne Regional Institute of Postgraduate Pedagogical Education, editor of the column "Overcoming the Past" on the website of Ukraїna Moderna, member of the editorial board of Eastern European Holocaust Studies, and guest editor of a special issue of Ukraina Moderna entitled The Holocaust in Ukraine: How the History of the Crime Is (Not) Written. He is the author of the monograph Svii do svoho po svoie: Sotsial′no-ekonomichnyi vymir natsiietvorchykh stratehii ukraїntsiv u mizhvoiennii Pol′shchi (Our Own People to Our Own for Our Own: The Socioeconomic Dimension of Ukrainians' Nation-Building Strategies in Interwar Poland [Rivne, 2018]), and the co-author, with Maksym Gon and Nataliia Ivchyk, of the monograph Misto pam'iati — misto zabuttia: Palimpsesty memorial′noho landshaftu Rivnoho (Town of Memory — Town of Oblivion: Palimpsests of the Memorial Landscape of Rivne [Rivne, 2019]). He is the author of most of the volumes in the series The Life and Death of Jewish Communities. He is currently researching the topic, "Property Hunters: Economic Factors Underlying the Behavior of the Non-Jewish Population of Western Volyn during the Holocaust," supported in 2023 by a Sosland Foundation Fellowship from the Jack, Joseph and Morton Mandel Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. He organizes training sessions, summer schools, roundtables, and academic conferences on history and politics; coordinates educational projects and museum exhibitions memorializing and popularizing the history of the Holocaust; and is one of the initiators of the exhibition A Brief History of Violence: The Second World War and the Holocaust in Western Volyn (curated by the civic organization After Silence). During his work with the Mnemonics Center for Studies of Memory Policy and Public History, he was one of the initiators and coordinators of the installation of commemorative markers in the city of Rivne honoring the victims of Nazism (modeled on "stumbling stones") and of a marker honoring Rivne ghetto victims. His research interests include the history of the Holocaust, the theory and practice of nationalism, and the politics of memory.

Petro Dolhanov is a Candidate of Historical Sciences, Assistant Professor of Pedagogy and Educational Innovations at the Rivne Regional Institute of Postgraduate Pedagogical Education, editor of the column "Overcoming the Past" on the website of Ukraїna Moderna, member of the editorial board of Eastern European Holocaust Studies, and guest editor of a special issue of Ukraina Moderna entitled The Holocaust in Ukraine: How the History of the Crime Is (Not) Written. He is the author of the monograph Svii do svoho po svoie: Sotsial′no-ekonomichnyi vymir natsiietvorchykh stratehii ukraїntsiv u mizhvoiennii Pol′shchi (Our Own People to Our Own for Our Own: The Socioeconomic Dimension of Ukrainians' Nation-Building Strategies in Interwar Poland [Rivne, 2018]), and the co-author, with Maksym Gon and Nataliia Ivchyk, of the monograph Misto pam'iati — misto zabuttia: Palimpsesty memorial′noho landshaftu Rivnoho (Town of Memory — Town of Oblivion: Palimpsests of the Memorial Landscape of Rivne [Rivne, 2019]). He is the author of most of the volumes in the series The Life and Death of Jewish Communities. He is currently researching the topic, "Property Hunters: Economic Factors Underlying the Behavior of the Non-Jewish Population of Western Volyn during the Holocaust," supported in 2023 by a Sosland Foundation Fellowship from the Jack, Joseph and Morton Mandel Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. He organizes training sessions, summer schools, roundtables, and academic conferences on history and politics; coordinates educational projects and museum exhibitions memorializing and popularizing the history of the Holocaust; and is one of the initiators of the exhibition A Brief History of Violence: The Second World War and the Holocaust in Western Volyn (curated by the civic organization After Silence). During his work with the Mnemonics Center for Studies of Memory Policy and Public History, he was one of the initiators and coordinators of the installation of commemorative markers in the city of Rivne honoring the victims of Nazism (modeled on "stumbling stones") and of a marker honoring Rivne ghetto victims. His research interests include the history of the Holocaust, the theory and practice of nationalism, and the politics of memory.

Originally appeared in Ukrainian @Ukraina Moderna

This article was published as part of a project supported by the Canadian non-profit charitable organization Ukrainian Jewish Encounter.

Translated from the Ukrainian by Marta D. Olynyk

NOTE: UJE does not necessarily endorse opinions expressed in articles and other materials published on its website and social media pages. Such materials are posted to promote discussion related to Ukrainian-Jewish interactions and relations. The website and social media pages will be places of information that reflect varied viewpoints.