Martin Dean: "The main site of the mass shootings was the western spur of Babyn Yar"

Recently, Lexington Books published Martin C. Dean's Investigating Babyn Yar: Shadows from the Valley of Death, a landmark book for Holocaust Studies in Ukraine. During our conversation with the author of this monograph, we discussed the main findings of his book and the arduous process of writing it. This is the first book about Babyn Yar to feature a complex analysis of both the mass killings during the Nazi occupation and a description of the further evolution of this site of memory. Among the author's key discoveries is the identification of the exact place where the mass killings of Jews took place on 29–30 September 1941.

"The book is built mostly around selected episodes, not told in chronological order"

Your new book, Investigating Babyn Yar: Shadows from the Valley of Death, was published recently. When and under what circumstances did the idea for this book come about? What was your key aim in setting out to write it?

The process of conceptualizing and writing the book dates back to 2019. Karel Berkhoff, the former Chief Historian for the Babyn Yar Holocaust Memorial Center (BYHMC), proposed using aerial photography to locate where specific ground photographs were taken and studying a series of key locations at Babyn Yar in close detail. I conducted much of this research in 2019-2020, writing more than 30 reports. I was surprised how effectively this approach led to a more comprehensive understanding of how the Nazis organized and implemented the massacre by exploiting the topography of Babyn Yar.

Karel and I applied for funding to write the book together in 2021, but this was turned down due to the urgent timetable for the 80th anniversary celebrations, and due to differences between Karel and the new leadership of the BYHMC under Ilya Khrzanovsky. Only in 2022 was my book proposal approved, and by then Karel was no longer involved. Interestingly, Karel never explained to me his own interpretation of the events at Babyn Yar, but he contributed greatly to developing the methodology, which I then implemented according to my own instincts as a historian.

The decision to write the book in an episodic, non-chronological way was something I developed, as I thought carefully about how best to put together the various pieces I had uncovered. Then, soon after I started writing, in February 2022, Russia invaded Ukraine, and I had to write most of the book without the BYHMC's financial support, feeling a strong obligation to complete my task, as there was a need for this story to be told. The main goal was to present a comprehensive account of what happened, using the voices of those who were present, but I also wanted to approach it in an interesting way, also telling the story of how I had solved some of the challenges I faced. [Image 1]

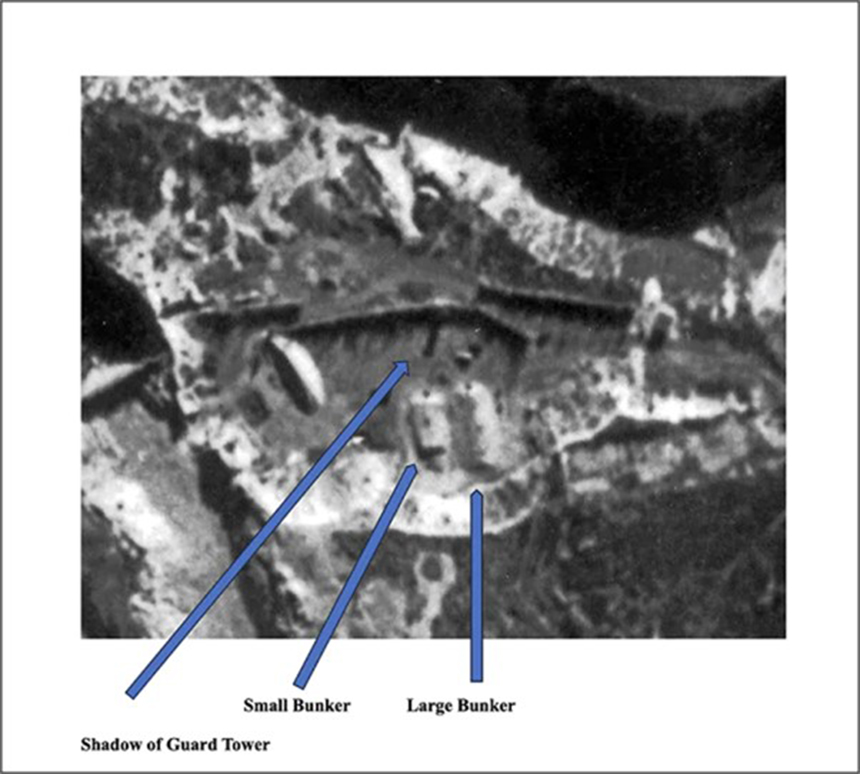

NARA, RG-373, GX 3938 SG, no. 105, September 26, 1943. (Image 2)

Please explain why your book is subtitled Shadows from the Valley of Death?

The title, Shadows from the Valley of Death, conveys different ideas. Firstly, the prisoners who were forced by the SS to exhume the bodies in August and September 1943 were called 'shadows' by the German guards as their fate had already been sealed. They were destined to be killed on account of their knowledge of the cover-up. But thanks to the escape of some of these 'shadows,' detailed testimony about the exhumation and the site of the main massacre was preserved. Secondly, the shadows visible in the aerial and ground photographs give us clues about the time of day when photographs were taken, and the existence of objects, such as guard towers, not visible directly in the photographs. [Image 2] Thirdly, there are also the lengthening shadows of post-World War II history cast by the Valley of Death, which change shape themselves as history advances and new interpretations become possible.

The structure of the book is quite unusual; it is more episodic than chronological. It is interesting, for example, that the first chapter begins not with a description of the pre-conditions and the course of the mass shootings on 29–30 September 1941, but with the year 1943, when prisoners of war were forced to dig up the remains of these murdered people and destroy evidence of this crime. Why did you choose such a structure for your research?

The structure of the book is mainly episodic rather than chronological. I chose this unusual structure for several reasons. Firstly, it reflects my own experience in piecing together the events of the massacre from a number of fragments that gradually coalesced into a more coherent understanding of the whole event. My first breakthrough came when I was able to identify on an aerial photograph the bunkers in the sand quarry, where the exhumation prisoners were housed. Therefore, I chose to open the story with this dramatic moment, when the prisoners were first led into the quarry to start the exhumations, in order to share the perspective of those who had to uncover the bodies, and slowly grasped the massive scale of the crime that had been committed here as their terrible work progressed.

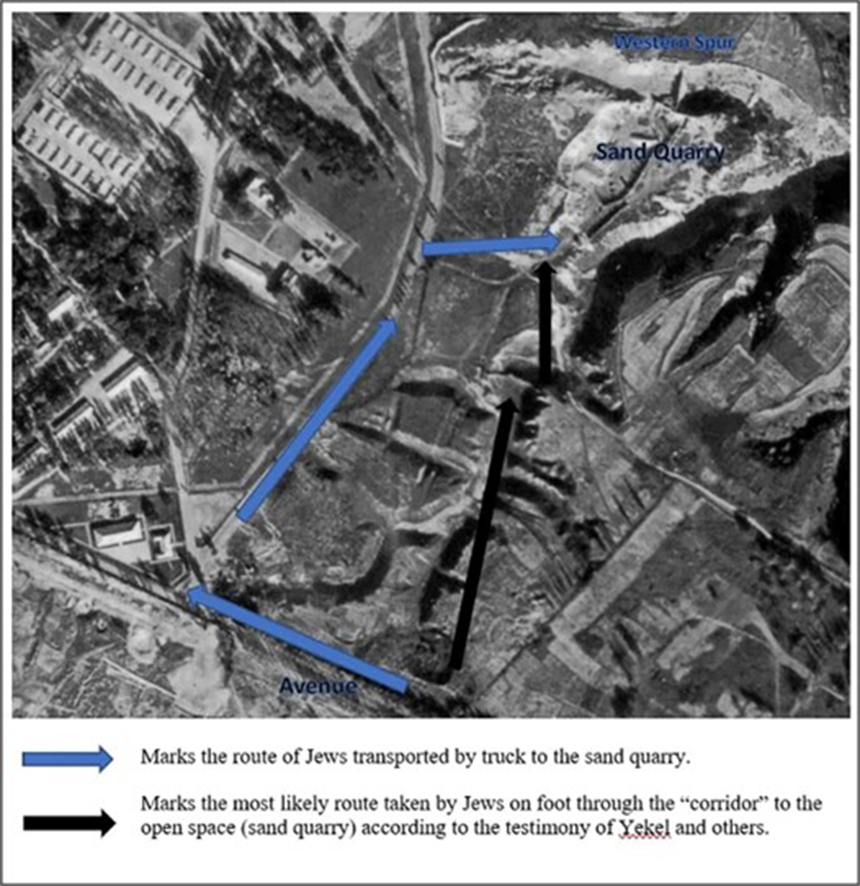

Each ensuing chapter then focuses on a key episode in the unfolding tragedy. Rather than just focus on the path that leads to Babyn Yar from the city, with various checkpoints in between, I go back to trace the murderous path taken by the killing units to get to Kyiv, as well as reconstructing the efforts made by some Jews to evacuate or flee the city before the Germans surrounded it. The main analysis is concerned with both how the massacre was conducted, as well as various efforts to cover it up. However, this narrative is interspersed with key events such as the 1961 mudslide, the Gestapo's treatment of various categories of prisoners during the occupation of Kyiv, as well as Soviet efforts to conceal the specifically Jewish nature of the main massacre site. This structure serves to increase the suspense, as I focus on telling the story through the direct evidence of photographs and eyewitnesses. I conclude by examining efforts to bring the perpetrators to justice, together with an overview of recent developments in Ukrainian memory politics at the site. [Image 3]

"I very much wanted to let the witnesses tell the story in their own words"

What were the main sources that helped you to write the book? You make active use of eyewitness testimonies. Here and there, it even seems as though we are listening to the eyewitnesses, while the author of the book fades into the background. It is as though you are the "eminence grise" who is influencing what we are reading about past events, but not intruding into the structure of these testimonies. Was this approach a conscious decision on your part?

Yes, I very much wanted to let the witnesses tell the story in their own words, so my job was to take the reader to the right place at the right time, to place the words into their proper context. My argument, of course, is that the full story has been available for people to discover all along, but it is only by gathering the testimonies together, along with other evidence, that we can really make sense of them and gain an accurate view of what actually happened.

At the BYHMC, I also worked closely together with Maks Rokmaniko and his team from Spatial Tech, who were charged with building a series of virtual and physical 3-D Models of Babyn Yar that were due to open at a special underground installation near the site in 2022. Working with Maks, I also developed the idea of trying to place specific quotations from witnesses within the physical space of Babyn Yar, and this contributed greatly to the writing of the book. In this respect the few photographs of what happened along the route were very helpful, as I was able to show what the witnesses were describing. [Image 4]

Your book systematically recreates the majority of the contexts behind the events in Babyn Yar, which are still being discussed in the historiography. What are your key discoveries?

This is a good question, as I was certainly dissatisfied with the previous accounts of Babyn Yar that I had read. I think that my real contribution has been to put all of these pieces together to make a more complete story, whereas previous efforts either misidentified the locations of key events or failed to explain the main logic behind the plans of the German Security Police. Some of the key discoveries came from very carefully studying the topography, enabling me to correct previous errors. Using the lone tree atop the crescent-shaped cliff as a reference point, I was able to determine the southwestern spur or branch of the ravine as the main site of the shootings. This is also confirmed by numerous witness testimonies that describe how Jews were driven into this ravine branch from the neighboring sand quarry, where they were forced to undress, as is shown also by the photographs of the discarded clothing. [Image 5]

The sand quarry is not shown on most maps of the area dating from before 1939 or after 1960, as it was only created just before the war started and was erased again by Soviet construction work after the war. This chronology was a major discovery that I made through careful detective work. In this way, I was able to correct some of the miscalculations made by colleagues, who had analyzed the terrain before me and come to rather different conclusions.

The incorporation of recently discovered photographs into the story helped considerably to document more precisely the route to the shooting site. I am indebted to various colleagues, especially Alexandr Kruglov, Karel Berkhoff, and Stephan Mashkevich, who brought to my attention some of these photographs. One of the tasks originally assigned to me was to help determine exactly where such photographs were taken. I eventually developed a practical methodology to determine this for several key photographs, and was gratified when colleagues, especially Maks Rokmainko, were able to confirm my conclusions, using their own 3-D modeling and other digital techniques.

As a result of my initial research, and especially the work of Maks and his Spatial Technology team, it has been possible to install viewing stones at several sites on the terrain of Babyn Yar, such that people can now view some of the Haehle photographs at the exact place where he was standing when he took them in 1941. This is an appropriate way of memorializing history, as envisaged by Karel Berkhoff several years ago. [Image 6]

There is still ongoing debate about where exactly the killings of the Holocaust victims took place on 29–30 September 1941. In your book you write that the site of the killings is different from the one indicated by Ukrainian researchers — Vitaly Nakhmanovych, for example (p. 110). What are your main arguments with regard to this question? How did you succeed in establishing the exact site of the mass shootings?

The advantage of my approach in carefully examining aerial photographs, ground photographs, numerous maps, and many testimonies, is that it was also self-correcting as many different sources ultimately led me to the one overwhelming conclusion. My work has also been vindicated by other members of the team, such as Aleksandr Kruglov, who are familiar with the evidence.

Essentially, I argue that the mass shooting took place in the western spur of the Babyn Yar ravine, as this is described in detail by numerous witnesses and is confirmed by the Haehle photographs, and other postwar films. Probably, the key photograph was that depicting Soviet POWs working along the length of the western spur to smooth over the ground. [Image 7] Nahmanovych made a useful contribution in publishing some of the KGB evidence collected in the 1980s, but these testimonies include inaccurate maps that may have contributed to Nahmanovych's mistaken identification of the killing site as being in the southern part of the main ravine. Given the strategic location of the sand quarry, where the massive piles of clothing were photographed, the suggested site in the main ravine does not fit logically into the German concept for the massacre, as the Jews would have to cross it to get to the undressing area. There is also no direct witness evidence to support this interpretation, whereas several witnesses describe how the Jews were escorted from the sand quarry over a slope and down into the western spur. Another theory about Jews being taken through the Jewish cemetery to be shot at the top of a high cliff [near the lone tree] can be discounted on a careful examination of the evidence. What remains uncertain is the full extent of the shooting area, and also the precise locations of some of the later mass shootings after September 30, 1941.

"It was racial ideology and not profit that fundamentally drove the Holocaust, and this was the case at Babyn Yar"

You devote one of the chapters in your book to the fate of victims' property. From the book's general context one gets the impression that, in the case of Babyn Yar, material benefits (the possibility of acquiring victims' property) played a subsidiary role in the process of committing the crime; rather, it was its consequence, not an important cause. Here and there, the economic factor played an uncertain role: In isolated cases, bribing perimeter guards helped individual victims to save themselves. As a researcher who studies the robbery of Jewish property, how do you assess this economic dimension of the events in Babyn Yar?

It is correct that robbery played only a subsidiary role in the events at Babyn Yar. However, the German Security Police took the material aspect into consideration from the start. The placards posted on September 28 [1941] told the Jews to bring valuables and certain other possessions with them; they also sternly warned the non-Jewish population not to plunder the empty apartments, on pain of death. The huge piles of luggage and clothing left along the route made this an event that those who observed it would never forget. Other documentation has survived about valuables seized by the Security Police at Babyn Yar, the fate of furniture left behind in Jewish apartments, and cultural goods looted by the Einsatzstab Rosenberg (the Nazi cultural looting office) in Kyiv. As I have argued in my book Robbing the Jews, Nazi looting, both private and official, almost always accompanied the murder of the Jews. It served to facilitate the process and cover the costs. Yet it was racial ideology and not profit that fundamentally drove the Holocaust, and this was the case at Babyn Yar, where most of the victims had only meager possessions. [Image 8] As you note, some Jews even managed to bribe their way out of the encirclement, although this did not guarantee that they would be able to survive the entire occupation.

Professor Dean, in Chapter 11 you raise the important question of postwar antisemitism and the Jewish pogrom in Kyiv that took place in September 1945. Can this pogrom be seen as a kind of "Ukrainian version" of the pogrom that took place in the Polish city of Kielce? There, the local population was hostile toward Jewish survivors because they were demanding the return of their property, particularly houses.

Yes, there is considerable evidence about this event and it resembles in some respects the pogrom in Kielce. There was also quite widespread hostility toward Jews that returned or arrived in Kyiv after the Germans were driven out, based on conflicts over apartments and jobs, although the situation was not as severe as in Poland. Another difference was in the origin of the pogrom; in Kyiv, a Jewish official took revenge on two local antisemites, whereas in Kielce, there were unfounded antisemitic allegations more in the tradition of a blood-libel.

Can we assume that Babyn Yar first became the quintessence of the evolution of the Nazi genocidal machine, a kind of infamous embodiment of all the results of its eight-year training on how to persecute and kill entire groups of people "properly"? As you write in your book, what lasted for ten years in Germany happened in Kyiv over a period of two days: The victims of the Holocaust were clearly identified, their property was confiscated, they were concentrated, and killed.

The significance of Babyn Yar is difficult to assess accurately. Even though it was the largest mass shooting conducted in the east, it was in some respects atypical of the general pattern of mass shootings. It certainly played a key role in the Nazi development of their killing methods; yet the organization and implementation actually occurred more rapidly here than in most other places. I argue, however, that it still resembled the process in Germany and other parts of Europe, as all the same stages were conducted — segregation, exploitation, concentration, and murder, but in a much more accelerated form than elsewhere. Interestingly, my conclusion is that some of the methods developed at Babyn Yar resembled those used in the extermination camps, as they were designed to deceive the victims for as long as possible in order to facilitate the smooth running of the killing procedure.

"In this war, it is the Russians who are invading and applying unrestrained imperialism together with brutal tactics toward the civilian population"

Your book ends with a description of the Russo-Ukrainian War as it is playing out today. On the one hand, Russian propaganda frequently instrumentalizes the Holocaust issue. On the other, it often sounds new in the Ukrainian public discourse. In your opinion, how has the perception of Babyn Yar changed as a result of the current war realities?

The Russian government, from the start, has tried to exploit the previously successful tactic of tying Ukrainian nationalism to Nazism. Yet, in this war, it is the Russians who are invading and applying unrestrained imperialism together with brutal tactics toward the civilian population. In this respect, the growing importance of Babyn Yar and the Holocaust since Ukraine's independence takes on a new significance; Russia's propaganda can be seen to be turning against itself, as the crimes of one brutal dictatorship cannot be exploited effectively to justify those of another. For this reason, Babyn Yar now also becomes a symbol of a dictatorship targeting innocent civilians in order to satisfy its extreme ideological goals. The considerable efforts of the Ukrainian government and the BYHMC over the last few years to commemorate Babyn Yar and respect its Jewish victims serve also to anchor Ukraine more firmly within democratic traditions and develop its civil society.

Can we expect a Ukrainian version of your book?

I would be pleased, of course, if there were to be a Ukrainian version of the book. I think that the first stage is for a Ukrainian publisher to approach Lexington Books to reach an agreement regarding the rights and royalties, and then the translation can proceed. I sincerely hope that this will be done.

The photographs used in this publication are from Martin Dean's private archive.

Martin Dean is a historical consultant who has worked together with many different organizations, including the Babyn Yar Holocaust Memorial Center, the Simon Wiesenthal Center, and documentary production companies like Caravan Media and DoubleBand Films. He has taught courses on the Holocaust and World War II for Kean University in New Jersey and given lectures at many colleges and memorial institutions. His scholarly interests are the history of the National Socialist dictatorship in Germany; the Holocaust and the Second World War in Eastern Europe; and the Nazi system of the economic exploitation of the Jews. His most distinguished publications include: Volume Editor of The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933–1945, vol. II, Ghettos in German-Occupied Eastern Europe (Bloomington: Indiana University Press in association with the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, 2012); Robbing the Jews: The Confiscation of Jewish Property in the Holocaust, 1933–1945 (New York: Cambridge University Press in association with the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, 2008); Robbery and Restitution: The Conflict over Jewish Property in Europe (New York, Oxford: Berghahn in cooperation with the USHMM, 2007); Collaboration in the Holocaust: Crimes of the Local Police in Belorussia and Ukraine, 1941–44 (London and New York: Macmillan and St. Martin's, 2000). Martin Dean has a reputation as one of the “most formidable” British investigators of war crimes. During his work as an historian at the Metropolitan Police War Crimes Unit, Scotland Yard, he took part in investigating over a hundred allegations of war crimes. During the trials in Germany in 1996–1998, he got two Nazi war criminals convicted. In 1999, he played a key role in the UK trial of Anthony (Andrei) Sawoniuk, who was given two life sentences.

Originally appeared in Ukrainian @Ukraina Moderna

This article was published as part of a project supported by the Canadian non-profit charitable organization Ukrainian Jewish Encounter.

NOTE: UJE does not necessarily endorse opinions expressed in articles and other materials published on its website and social media pages. Such materials are posted to promote discussion related to Ukrainian-Jewish interactions and relations. The website and social media pages will be places of information that reflect varied viewpoints.