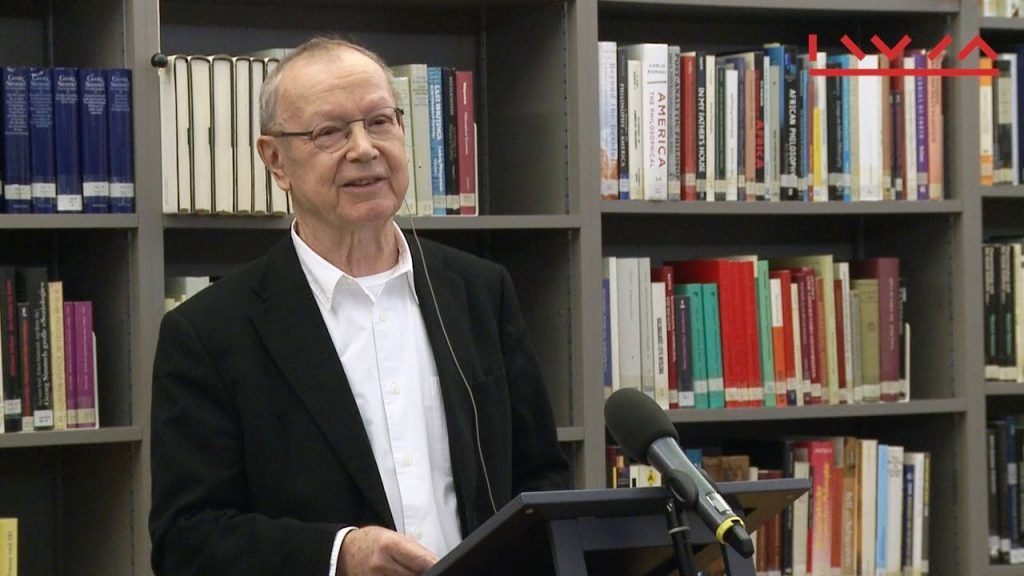

Martin Pollack devotes life to deconstructing "Galician myths"

“How are we to explain the fact that today many people all but yearn for a world destroyed by their fathers and grandfathers?”

The Austrian writer Martin Pollack poses uncomfortable questions in his work. But then he hails from a less than comfortable background.

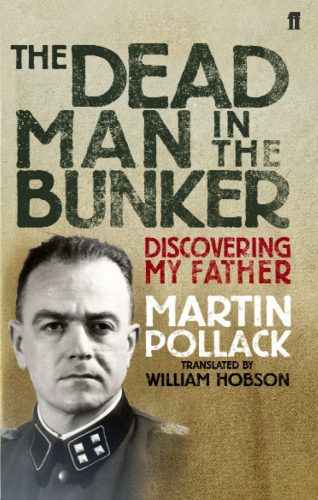

Pollack’s powerful book, The Dead Man in the Bunker, carries the subtitle “Discovering My Father.” It is the story of a man found murdered in 1947 in the mountains between Austria and Italy.

The murdered man is not what his papers claim him to be. The dead man is in fact Dr. Gerhard Bast, a highly ranked SS officer who commanded death squads in Eastern Europe and was former head of the Gestapo in the Austrian city of Linz. And this man had an affair with a married woman that led to the birth of a son, Martin Pollack.

Pollack grew up knowing nothing of the circumstances of his father's death or his involvement in Nazi atrocities. Pollack’s grandparents were ardent and unrepentant Nazis. But Pollack himself escaped their influence thanks to his mother, who sent him to a boarding school in the mountains. There he met the children of people who had been displaced by the war. And that is where he says he heard the first sounds of Slavic languages.

In rebellion, Pollack broke off contact with his family and finished a degree in Polish studies. He launched into a career in journalism.

Ironically, Pollack’s interest in Poland was stymied by the then communist authorities who barred his entry into the country from 1980 to 1989. He looked for new fields of interest in Eastern Europe and discovered Galicia.

He wrote the book To Galicia: Of Hassidim, Hutsuls, Poles, and Ruthenians. An Imaginary Journey Through the Vanished World of Eastern Galicia and Bukovina. And a lifelong passion for the subject was born.

In a recent interview with Iryna Slavinska for Ukrainska Pravda, as well as in an expanded lecture called “The Myth of Galicia” in Toronto, Pollack outlined the complex and contradictory perceptions of Galicia. He described the challenges of competing memories and comforting illusions. And he identifies the toxic legacy of the colonial gaze of the supposedly more civilized Western world on the exotic East.

In a recent interview with Iryna Slavinska for Ukrainska Pravda, as well as in an expanded lecture called “The Myth of Galicia” in Toronto, Pollack outlined the complex and contradictory perceptions of Galicia. He described the challenges of competing memories and comforting illusions. And he identifies the toxic legacy of the colonial gaze of the supposedly more civilized Western world on the exotic East.

Galicia was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire up to 1918. The enlightened empire provided emancipation for the Jews, and institutionalized nation-building for both Poles and Ukrainians.

But, as Pollack points out, for many Austrians—and by extension the German-speaking world—it was considered foreign, distant, and almost hostile. A “Half-Asia” that did not quite belong.

It was also the poorhouse of the empire, “the land of the poor and the hungry” in a Polish proverb. Pollack relates an astonishing story of how Jews would go through the villages in the Carpathian Mountains in spring and buy sheepskin coats from peasants. The coats would not be needed in warm weather. They would mend them and resell the coats again in the same villages in autumn so that at least one person in a family can go outside in winter.

This grinding poverty sent massive waves of exploited Jewish, Polish, and Ukrainian migrants to distant shores in a desperate search of a better life, a story Pollack relates in his book Emperor of America: The Great Escape From Galicia.

Poverty provokes pity, but also contempt. Pollack reminds us Hitler first met Galician Jews in Vienna before the First World War and expressed his hatred in Mein Kampf.

That war intensified the negative stereotypes of Galicia, as Austrians and Germans experienced what Pollack calls the “Galician hell” of hunger, lice-ridden trenches, large-scale slaughter, and wretched death. The soldiers had cameras, and photos of the “aborigines” in folk costumes, or in rags before ruined dwellings, or being hastily executed for supposed treason or espionage consolidated a certain Western condescending gaze.

Pollack recalls how he recently was given a family photo album from that era that was found in a flea market. Among pictures of a military officer with his family is to be found a photo of a Ukrainian peasant hanging from a tree, surrounded by a crowd. The album was entitled “My Memories of the War.”

Of course we have even more horrific photos from the Second World War, with, as Pollack underlines, crowds gathering to witness a n “event.”

The Second World War destroyed Galicia as a multi-ethnic and multi-cultural society. But Pollack notes that paradoxically a world that once aroused rejection and revulsion is now viewed by many in the German-speaking world in a warm glow of positive nostalgia. An idyllic world of harmony. Galicia in the West is still mainly associated with a “Jewish” identity. In Austria, Poland, and the U.S. “Galitzianer” means “Jews.”

Pollack wryly observes, “Our parents, our grandparents killed this world, destroyed this world, and now our generation thinks this is a most interesting, fantastic world.”

And yet the Western gaze remains skewed. Pollack laments the fact that Ukrainian Galicia still remains too little known among Westerners. He attributes this to the lack of translations of Ukrainian literature. He promotes Ukrainian writers and sharply notes that Austria was amazed to discover there were Ukrainian writers in Ukraine.

Pollack says, "We must work to enable each one of us to tell our story in our own language, but we must also be able to listen and hear others."

Pollack refers to himself as the “destroyer of Galician myths.” But these myths still hold a fascination for him. He published his first book on Galicia in 1984. And he reflects, “In 2017, I am still in the field of Galicia. This land has become my imaginary homeland.”

This has been Ukrainian Jewish Heritage on Nash Holos Ukrainian Roots Radio. From San Francisco, I’m Peter Bejger. Until next time, shalom!

Written and Narrated by Peter Bejger

Listen to the program here.

Ukrainian Jewish Heritage is brought to you by the Ukrainian Jewish Encounter (UJE), a privately funded multinational organization whose goal is to promote mutual understanding between Ukrainians and Jews. Transcripts and audio files of this and earlier broadcasts of Ukrainian Jewish Heritage are available at the UJE website and the Nash Holos website.