Martin Schulze Wessel: "The goal of the Russian war is annihilation"

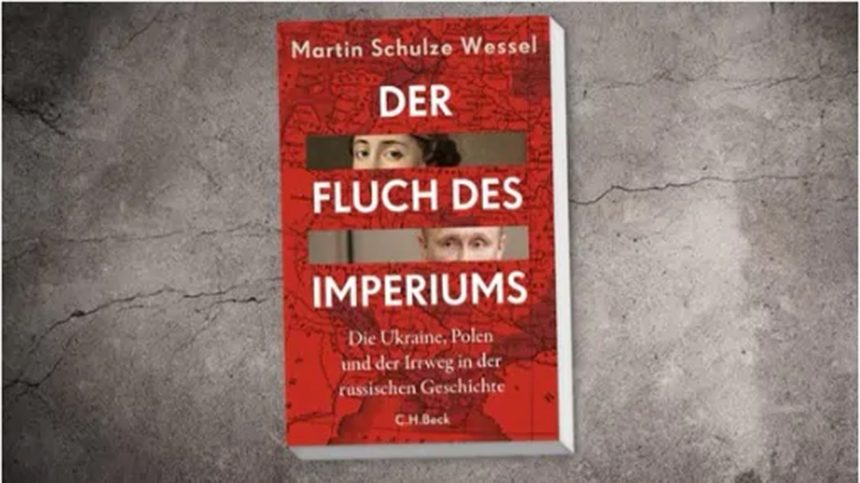

In the following interview, the well-known German historian and former head of the German-Ukrainian Historical Commission discusses the Russo-Ukrainian War and the roots of Russian imperialism. He reflects on these very topics in one of his most recent books, Der Fluch des Imperiums (The Curse of the Empire: Ukraine, Poland and the Misguided Path in Russian History). We talked about imperialism and colonialism, the question of when Russian imperialism arose, and the kinds of threats that it poses to the contemporary world order.

"After 1991, Germany's guilt towards the peoples of the Soviet Union was only associated with Russia, as the successor state of the Soviet Union"

It took the German public a long time to grasp the true nature of Russian aggression against Ukraine. In your view, why was it such a lengthy process? How could the history of the Second World War and the Holocaust have helped make an impact on it? To what extent could this have been due to certain trends toward a Russocentric view of Ukraine?

In fact, the German public did not understand the nature of Russia's aggression against Ukraine for a long time. There are forces on the left and far right of the political spectrum that trivialize Russian policy and propagate the opinion that we must negotiate with Putin. Apart from economic reasons, there are also reasons in the historical discourse that have long prevented the true nature of Russian imperial policy from being recognized. The history of the Second World War plays a role in this. After 1991, Germany's guilt towards the peoples of the Soviet Union was only associated with Russia — as the successor state of the Soviet Union. However, the equation of the Soviet Union with Russia has older roots. As late as the 1950s, people often spoke of Russia as a matter of course when referring to the Soviet Union. With regard to the Second World War, this meant that there was only a sense of guilt towards the Russians in Germany. However, there were many more victims of the German occupation in Ukraine and Belarus.

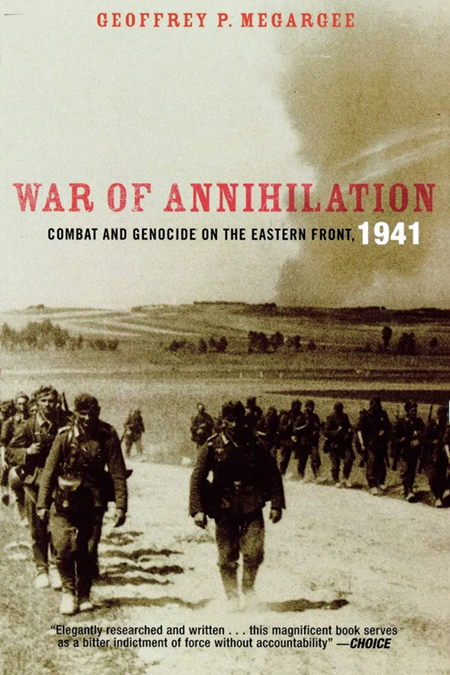

In the 1980s, there was a dispute between historians in Germany (Historikerstreit) about the comparability of the crimes of National Socialism with the crimes of other regimes, especially Bolshevism. The opinion has prevailed that the Holocaust is a crime of its own kind due to the systematic way in which this crime was carried out. I believe it is right to regard the Holocaust as a unique crime. But the focus on Germany's own crimes, which is correct in itself, has also had questionable consequences for the political-historical discourse. The singularization of the Holocaust involves the danger that other crimes may be ignored or marginalized. To give one example: During the Russian-Ukrainian war, a German contemporary historian criticized the fact that Russia's conduct of the war was described as a "war of annihilation" (Vernichtungskrieg). He wanted to reserve this term for the designation of German occupation crimes during the Second World War. Because the German crimes were unique, in his opinion they should also be labelled with special — non-transferable — terms. However, it is absurd not to describe the Russian war against Ukraine as a war of annihilation, because Russia is not only concerned with defeating the Ukrainian army but is also waging a war against the civilian population through the systematic bombing of cities and the targeted destruction of civilian infrastructure. The aim of the Russian war is annihilation.

What role does the past play in the legitimization of Russian aggression today? How is the Kremlin's propaganda instrumentalizing it?

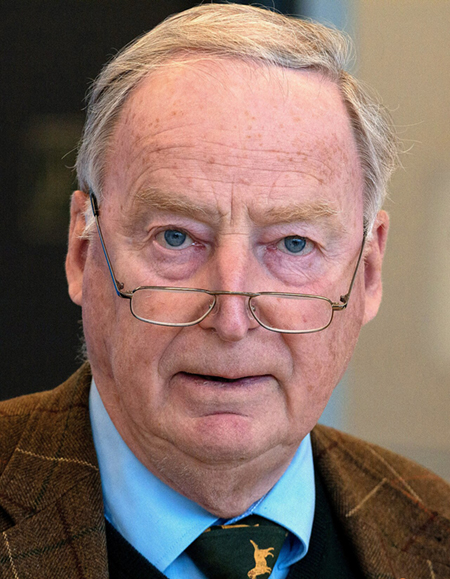

Kremlin propaganda pulls out all the stops to influence the public with historical arguments. At the beginning of the war, there were arguments that were specifically tailored to the German public and were readily taken up by the far-right party "Alternative for Germany," especially by Alexander Gauland. The propaganda explicitly or implicitly referred to the tradition of Prussian-Russian or German-Soviet relations. The myth was spread that there was peace in Europe when Germany and Russia had good relations. What nonsense when you think of the partition of Poland or the Hitler-Stalin Pact!

Today, the relationship with the global South plays a major role in Kremlin propaganda. Russia ascribes to itself the role of an ally with the countries of the Global South. The message of today's Russian propaganda is that Russia stands in solidarity with the countries of the Global South. Of course, this is a huge historical and political lie. It conceals the fact that Russia itself was and is a colonial power. It has colonized a huge empire of land: Siberia, the Caucasus, Central Asia, and the Far East. It wages an imperial war with genocidal dimensions against Ukraine and pursues colonial interests in Africa and other parts of the world.

"What the empires of Western Europe and Russia had in common was that they were colonial empires, that is, they had been involved in the subjugation of the world since the early modern period."

In the new edition of your book The Curse of Empire, you propose seeking the roots of modern Russian imperialism in the age of Peter I. What are the historical origins of Russia's current policy of aggression? How far back into the past must one look?

A distinction must be made between an imperial idea and an imperial setting that has structural consequences. An imperial idea already existed in Russia before Peter I, as early as the 16th century. In the time of Peter I, something new was added: in the Great Northern War, Russia gained supremacy in the Baltic Sea and in Eastern Central Europe. When Russia conquered Sweden's Baltic provinces, turned Poland into a de facto Russian protectorate and subjugated the Ukrainian Hetmanate of Mazepa, it became clear that Russia was assuming a hegemonic position in Eastern Europe. This gave rise to the first East-West conflict in modern European history during the Northern War. In the final phase of the Northern War, England attempted to form an international alliance with Sweden and Saxony-Poland in order to push Russia back. In this conflict, Russia managed to win Prussia over to its side, with which it was linked by anti-Polish interests. Half a century before the first partition of Poland, the new structure of the international system in Eastern Europe was already emerging: Russia, the Habsburg Monarchy and Prussia formed an imperial bloc that was sometimes directed against London, sometimes against Paris. Conflicts between the three imperial states were the exception. Supported by Berlin and Vienna, St Petersburg's policy in the 19th century dominated the so-called Congress Poland, which was created at the Congress of Vienna in 1815. Polish uprisings constantly challenged Russia's position of power in East-Central Europe. When the Ukrainian national movement gained more and more support among the ethnic Ukrainian population in the last third of the 19th century, St Petersburg politicians were alarmed because they perceived the Ukrainian question through the lens of the Polish question. The Russian government reacted extremely sensitively to the stirrings of the Ukrainian national movement because it feared that it could give rise to a challenge that was similar to the Polish national movement. The aggressive policy against the Ukrainian national movement, e.g. through the anti-Ukrainian language policy, resulted from St Petersburg's fear that the success of the Ukrainian national movement would jeopardize the Russian empire, but also the great Russian nation.

How did the Russian Empire differ historically from other empires, in particular Western ones?

What the empires of Western Europe and Russia had in common was that they were colonial empires, that is, they had been involved in the subjugation of the world since the early modern period. Russia built a land empire by conquering Siberia, the Caucasus, the Middle East and the Far East, while the Western European empires were maritime empires. A decisive difference between Russia and the Western European empires is that Russia also built its empire inside Europe. The annexation of the Hetmanate, the Baltic states, Poland and Finland enlarged the empire within the European continent. From the beginning of the 19th century, this gave rise to an emancipation movement that challenged the Russian empire with European, Western-influenced concepts: self-determination, democracy, federalism and the nation state. The emancipation movements, especially those of the Poles, won the sympathy of Western liberal public opinion, even in the German territories of the 19th century. Even in the 19th century, Russia's only response to national and democratic mobilization was excessive violence. This is similar to Russia's actions against democratic Ukraine today.

"It was often precisely the European-oriented politicians and commentators who called for Russia's imperial path and supported it with all its consequences."

All too often Russian imperial history is interpreted within the parameters of a confrontation between "good" Westernization and the "bad Asian" despotic tradition. What are the shortcomings of such a binary approach?

This approach is very misleading, not only in the popular discussion about Russia, but also in parts of academia. The division into "good Westerners" and "evil" supporters of Asian despotism fails to recognize that it was often precisely the European-oriented politicians and publicists who called for Russia's imperial path and supported it with all its consequences. Unfortunately, this is often not recognized, at least not in Germany and Western Europe. Peter I was not only the tsar who fought against old Russian traditions and, for example, cut off the beards of Russian nobles and had a new capital built in the European style, but he was also the founder of a Russian hegemonic policy within Europe. A liberal politician like Petr Struve was a fervent advocate of an imperial-nationalist policy of the Tsarist Empire at the beginning of the 20th century. Even Aleksei Navalny, Putin's most courageous democratic opponent, held on to imperial thinking and clichés for a long time, but clearly distanced himself from them after February 2022 when he spoke of the need to overcome imperial autocracy in Russia. Many democratic Russians, as well as many Western observers, do not recognize that the two are connected, the empire and the autocracy.

What kinds of challenges did the Russian Empire encounter during its expansion to the West? Why did the conquest of the territories of Poland and Ukraine give rise, in a sense, to an identity crisis in the empire itself?

Russian politics met the challenge of the Polish and Ukrainian national movements, which were based on modern political programs: self-determination, federalism and democracy. In the first half of the 19th century, Polish and Ukrainian national poets formulated their program in a messianic form: Mickiewicz or Shevchenko understood their role as mouthpieces and prophets of their nation. The downfall of the nation was linked to the idea of resurrection. This messianic nationalism had no weapons, but in the long term, it proved to be stronger than the imperial nationalism that Pushkin advocated in Russia in 1830/31.

Russian politics met the challenge of the Polish and Ukrainian national movements, which were based on modern political programs: self-determination, federalism and democracy. In the first half of the 19th century, Polish and Ukrainian national poets formulated their program in a messianic form: Mickiewicz or Shevchenko understood their role as mouthpieces and prophets of their nation. The downfall of the nation was linked to the idea of resurrection. This messianic nationalism had no weapons, but in the long term, it proved to be stronger than the imperial nationalism that Pushkin advocated in Russia in 1830/31.

The national identity of the Russians did not develop within clear boundaries, but in concentric circles: There is a "we"-community of ethnic Russians, as well as the Great Russian idea of a national community of Russians, Ukrainians and Belarusians, and even more far-reaching Slavophile and Eurasian concepts. If you don't know where your own nation ends, it is difficult to build a democracy, which is based on the boundaries of an electorate. The combination of nationalism and imperialism is highly problematic for the historical development of a nation. This can be seen not only in the Russian example, but also in the German example. For example, the German writer Gustav Freytag (1816–1875), who was regarded as the epitome of the bourgeois liberal, published the novel Soll und Haben [Debit and Credit] in 1855, which quickly became a bestseller and was made into a film in 1924. The novel was born out of a need for national self-assurance, at the same time, the liberal writer was characterized by anti-Semitic and anti-Polish resentment. Freytag's concept of his own German nation was inextricably linked with chauvinism and imperial claims. There are many figures like Gustav Freytag in Russia, both in the 19th century and in the present day.

"The new world order that Beijing and Moscow are striving for is an imperial and colonial one."

In the 1990s the distinguished geopolitical strategist and expert Zbigniew Brzezinski declared that without Ukraine, Russia ceases to be an empire. To what extent do such views explain reality, and to what extent do they shape it, provoking the Russian political elites to capture Ukraine?

In the 1990s the distinguished geopolitical strategist and expert Zbigniew Brzezinski declared that without Ukraine, Russia ceases to be an empire. To what extent do such views explain reality, and to what extent do they shape it, provoking the Russian political elites to capture Ukraine?

One problem with geopolitical discourses is that they are not critical but take the perspective of politics. Brzezinski's sentence is a correct statement about the thought patterns of Russian politics, and at the same time, it has reinforced these thought patterns, as Brzezinski has been read in the Kremlin. The problem with the statement is that Brzezinski takes Russia's imperial ambitions for granted and thus legitimizes them. Of course, Russia could guarantee its own security without Ukraine. Only if Russia wants to exercise imperial hegemony over Eastern Europe does it need Ukraine, not for its own security.

What is the likelihood that Russia will reject its imperial identity? What is necessary for this?

This path will definitely be very difficult and take a long time. One condition for the possibility of such a path is Russia's defeat in the war against Ukraine. Only then is there a chance (not a certainty) that Russia will shed its imperial myths. In Germany, this was only possible after the defeat in the Second World War under the conditions of Western occupation. The occupation was a favorable condition for a new beginning, which will not exist in Russia.

In modern studies of imperialism, it has become customary to distinguish colonialism from imperialism as a special form of expansion generated by the West. For example, Joseph Grim Feinberg writes about this. In some cases, a unique path of development is attributed to the West, and in others—the creation of a unique form of evil. However, neither of these approaches contradicts the notion of "uniqueness." Can one speak about colonialism as one of the faces of imperialism?

There is indeed a Eurocentrism in the assessment of expansions. The Mongol invasion of Europe is seen categorically differently from European expansions into non-European regions. The distinction I make between "imperial" and "colonial" concerns the form of rule: imperial is rule, as John M. MacKenzie has put it, when it is exercised by an "expansionist state system" that "has various forms of sovereignty over a people or peoples whose ethnicity is different from (and in some cases, the same as) its own." The empire is a "politically composed unit, usually with a ruling center and dominated peripheries." The forms of hegemonic rule can be very different. Colonialism is a special form of hegemonic rule. Colonizers and colonized are generally alien to each other. Colonial rulers are convinced of their own superiority over the "primitive peoples," sometimes relying on theories of racial superiority.

In the contemporary world, is empire as a form of the political organization of space something exceptional, or has it been preserved as an alternative to democratic national states? After all, besides Russia, arguably the oldest empire in the world—China—has retained its significance.

Russia and China are pursuing the goal of replacing the democratic and the existing international order. This order is based on international law, which protects the sovereignty of all states, including the militarily weaker ones. The new world order that Beijing and Moscow are striving for is an imperial and colonial one. Paradoxically, however, Moscow is trying to present itself as the avant-garde of post-colonialism. At the International Economic Forum in Saint Petersburg in June 2024, participants were shown a short film before the event, which first showed the crimes of European colonialism since the 15th century. The film then showed the history of Russia, the only country to have successfully resisted European colonization, citing as examples the Russian victories against Sweden under Charles XII, against France under Napoleon and against Germany under Hitler. Russia is shown in the film as the supposedly strongest supporter of the oppressed peoples of the global South. Thanks to Russia — according to the film — a "new era of global justice" will dawn. Not a word about the fact that Russia itself was a colonial power in many parts of Asia, not a word about Russia's current colonial practices in Africa, not a word about the Holodomor and the current war against Ukraine!

However, there is little to suggest that the empire will disappear as a form of rule in the foreseeable future. The Russian Federation is an empire, and China has a long imperial tradition. In the long term, however, I still believe that the nation state and democracy will prevail. Also in empires, people long for self-determination. This desire can be suppressed by state repression, but not for very long. The reverse case — people in democracies who wish to be subjugated to an empire — is much less common. The greater appeal of the Western order remains and will, in the short or long term, cause legitimacy problems for autocratic empires.

Interviewed by Petro Dolhanov

Photos from the Internet were used in this publication.

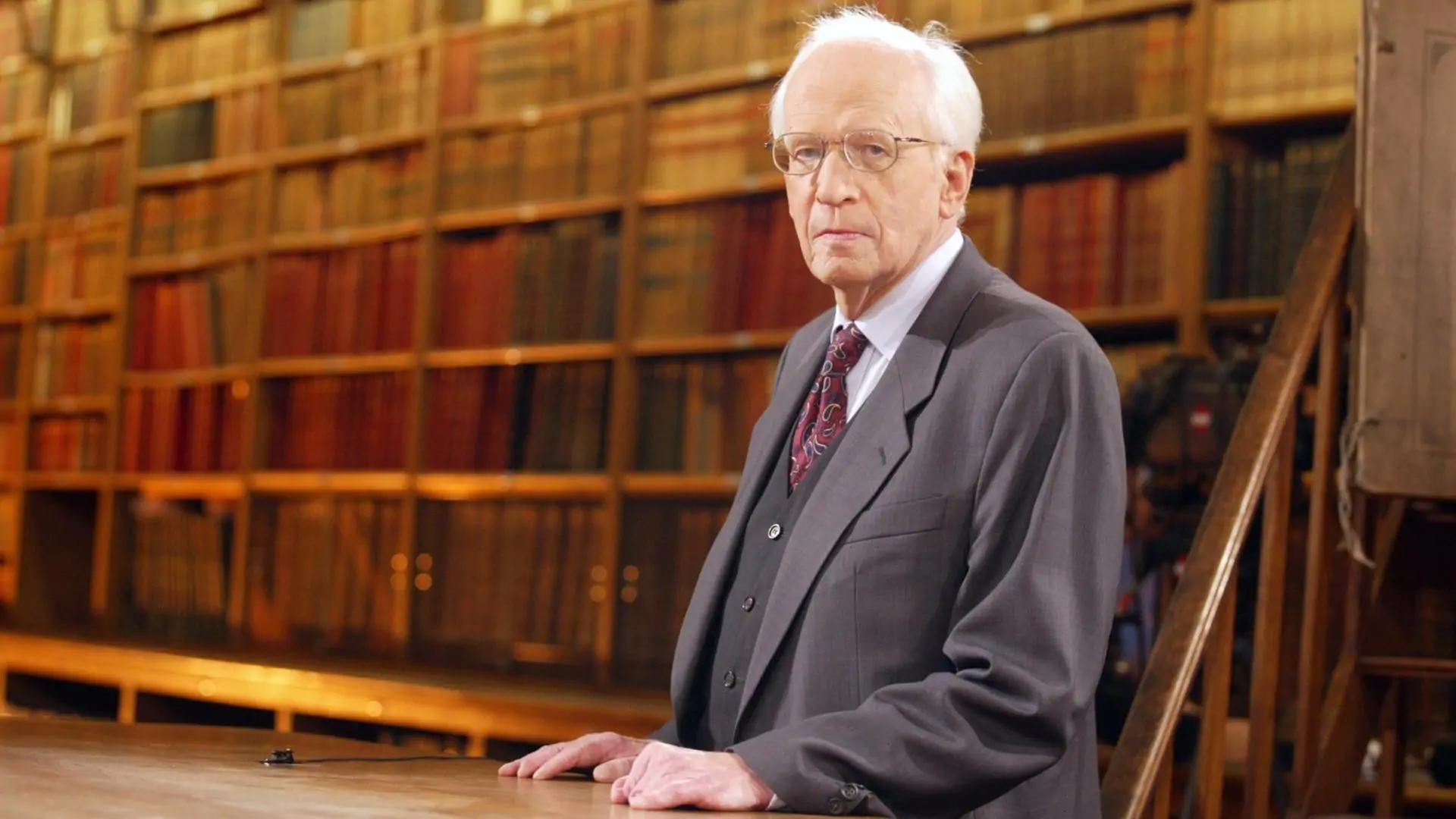

Martin Schulze Wessel is Professor of Eastern European History at the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich. In 2014, he and Professor Yaroslav Hrytsak of Ukraine founded the German-Ukrainian Historians Commission.

Originally appeared in Ukrainian @Ukraina Moderna

This article was published as part of a project supported by the Canadian non-profit charitable organization Ukrainian Jewish Encounter.

Additional translations from the Ukrainian by Marta D. Olynyk.

NOTE: UJE does not necessarily endorse opinions expressed in articles and other materials published on its website and social media pages. Such materials are posted to promote discussion related to Ukrainian-Jewish interactions and relations. The website and social media pages will be places of information that reflect varied viewpoints.