Museum of the Jewish People: What is Israel’s latest tourist attraction about?

Opened in the spring of 2021 after a large-scale renewal that lasted for ten years, the former Museum of the Diaspora got a new name, a new concept, and a totally updated exhibition. I spent time there recently and assessed the creators’ original view of the history and modernity of the Jewish people, including the history of Ukrainian Jews.

The Museum of the Diaspora at Beit Hatfutsot opened in May 1978 on the campus of Tel Aviv University on the initiative of Nahum Goldmann, founder and president of the World Jewish Congress, who sought to create a monument of the Jewish Diaspora. The monument was indeed a success, but it was in fact a dry and “mummified” collection of mock-ups and evidence of a bygone world.

The very creation of such a museum in the first Zionist city in the world was an extraordinary event because, for many decades, the ideology of Zionism was based on repudiating the Diaspora and breaking with it. At the time, there was a prevailing notion in Israel about the need “to create a new Jew—an Israeli, who should rid himself of Diaspora complexes and the memory of past humiliation.” An understanding of the importance of the Diaspora and the rich heritage of Jewish communities in various countries was late in coming.

The team that modernized this museum took one step farther. They created a Museum of the Jewish People, uniting the motifs of Israel and the Diaspora into a single whole. This is precisely why the short name of the new museum is “ANU,” which means “we” in Hebrew.

The “ANU/We” concept encompasses the entire Jewish people as such, a global ethnoreligious corporation alone in its diversity, with its “home office” in Israel and “branches” all over the planet—in the past, present, and future.

The new team behind the creation of ANU began to be formed in 2004, when Leonid Nevzlin, an anti-Putin billionaire who left Russia after the arrest of his business partner, Mikhail Khodorkovsky, moved to Israel. The then prime minister of Israel, Ariel Sharon, advised Nevzlin to help revive the moribund Museum of the Diaspora.

Through his NADAV Foundation, Nevzlin invested thirty million (US) dollars into modernizing the museum. A total of one hundred million (US) dollars was raised over a period of ten years from various sources, including private donors and state budgets. With an exhibition area of seven thousand square meters, ANU is one of the largest Jewish museums in the world.

Irina Nevzlin, the businessman’s daughter and wife of Israel’s current Minister of Health Yuli Edelstein, who was born in Chernivtsi, heads the Board of Directors of ANU Museum. During our meeting, Irina said that in the last few years she has dedicated her life to one thing: renovating the museum. She has put all her strength and energy—and her soul—into this gigantic project.

The exhibition in the new museum begins at the top, not the bottom. Visitors do not follow the traditional path from the distant past to the current era. On the contrary: the first thing that visitors see is the third floor, which shows the Jewish people in the present time.

The exhibits, stands, and departments on the third floor seem to say: “Today we are the way we are; we are not like each other, and we live differently, but we are one people despite all of our mosaic-like nature, and we have made a huge contribution all over the world.”

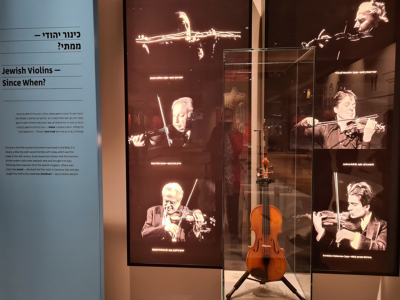

Jews in literature, music, theater, film, painting, and science—all these themes are presented colorfully, fascinatingly, and interactively.

The most cutting-edge digital technologies are utilized. Every object and stand conducts a conversation with visitors, allowing them to learn more with just one click.

The electronic Jewish kitchen, for example, enchanted my wife, who kneaded dough and added various ingredients by moving her hands on the screen.

Among the museum’s unique exhibits are a painting by Chaim Soutine, Franz Kafka’s first publication, a pen that belonged to Sholem Aleichem, Isaac Bashevis Singer’s typewriter, a lace collar that belonged to U.S. Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, one of Leonard Cohen’s guitars, a wig worn by Solomon Mikhoels playing the role of King Lear, and many other objects.

Although some exhibits reveal the fate of Soviet Jews (a book by Isaac Babel, stands dedicated to the actor Arkady Raikin and to those who fought for repatriation to Israel), the main part of the museum is imbued with the spirit of Americentrism and mass culture. For example, an old pair of Levi’s jeans hangs in the window of the museum. One is left with the impression that many elements of the exhibition are designed primarily for the global perception of American tourists.

The second floor of the ANU Museum reveals the historical path of the Jewish people among the world’s nations. The past is shown as a road passing through countries and epochs. The creators of the museum did not delve deeply into specific countries or historical periods.

The fate of the Jews is shown in broad brushstrokes through major transformations and events. Visitors who want more detail can obtain electronic information about each specific country.

For example, I scrolled through digital information about Ukraine and the history of the Jews in the Ukrainian lands. Although the information was objective, I spotted several unfortunate errors, including inaccurate historical dates, the number of Jews killed on Ukrainian lands during the Holocaust and the English-language spelling of Ukrainian cities. These and other mistakes can be easily corrected with the help of scholars, and I hope that the managers of the museum pay attention to this.

When I spoke to Dan Tadmor, the CEO of ANU Museum, I also broached the question of the Jews of Ukraine, a topic that, in my view, is weakly represented. Tadmor emphasized that it was a deliberate choice not to delve into detail into specific countries but to show the Jewish people's historical path through a global perspective.

Tadmor noted that he will always be pleased to study proposals about preparing and holding specialized exhibitions on themes related to Jewish communities living in various countries, including Ukraine. “The main thing is to find a serious, interested partner for realizing such a project,” he said.

On every floor of the museum, I saw adults and children intently studying artifacts and using the interactive screens. People were laughing and rejoicing at discovering something new about the old but forever young Jewish people.

ANU has turned out to be a very delightful and ironic museum that not only shows the great achievements of Jews but also offers visitors an opportunity to laugh at themselves.

“We want to show that there is not just Gewalt [Help!] in Jewish history and modernity but also ‘Alleluia!’” remarked Orit Shaham Gover, Chief Curator of the museum.

I left ANU Museum armed with historical optimism, probably the most important impression of this beautiful museum, which has definitely become a top tourist attraction not only in Tel Aviv but all of Israel.

Video from the ANU Museum

Text, photos, and video: Shimon Briman (Israel).

Translated from the Ukrainian by Marta D. Olynyk.

Edited by Peter Bejger.