Mykola Krasovsky: From the Beilis affair to the Intelligence Service of the Ukrainian National Republic

[Editor’s note: In Kyiv in 1913 Mendel Beilis, a Jew, was accused of the ritual murder of Andrii Yushchynsky, a 13-year-old Ukrainian boy. Mykola Krasovsky, the lead investigator of the Kyiv Police Department, carried out an investigation during the pre-trial period. Krasovsky was eventually fired because of resistance and sabotage on behalf of those interested in railroading the accused. Beilis was subsequently acquitted by a jury comprised of Ukrainians. In 2018 the historian Oleksandr Skrypnyk discussed Krasovsky’s role in the Beilis trial and in the Ukrainian National Republic. His article is below.]

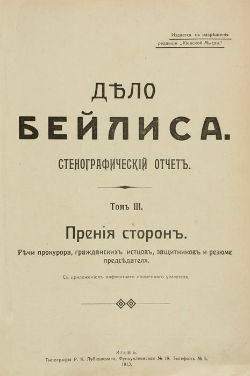

One hundred and seven years ago a high-profile murder took place in Kyiv, which captured the attention of practically the entire world for nearly three years. The murder of a boy, a bloody libel against all Jews, and an honest investigator, who turned the search for the real killers into a matter of personal honor.

One individual who was perfectly apprised of all the turning-points in the high-profile killing of Andrii Yushchynsky, a thirteen-year-pupil pupil at St. Sophia Theological College, in Kyiv on 12 March 1911, and of the smallest details of the investigation of the criminal case that came to be known throughout the world as the “Beilis affair,” was Mykola Krasovsky. For him, bringing to justice the real killers, not those who had been railroaded by interested parties, became a matter of honor and, in fact, the case of his life.

These reflections were inspired by research on Krasovsky’s biography during the writing of a book on famous intelligence agents of the Ukrainian National Republic era and the shooting of a documentary film about this extraordinary figure.

His photograph, the only one that has survived to the present day, occupies a key place in a museum devoted to the history of national secret services. I came across his statement about what a true intelligence officer should be like not just among the museum’s exhibits, but even on the doors and safes of some bureaus of officers working in Ukraine’s Foreign Intelligence Service.

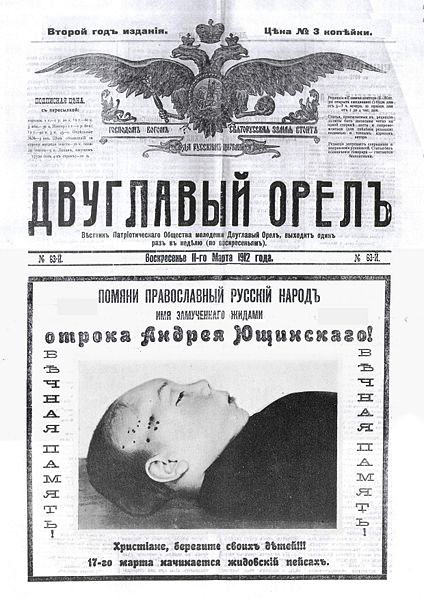

At the same time, I was compelled by other circumstances to revisit that old, long-forgotten case. Those famous events, which were inspired by high-ranking members of the Black Hundreds from St. Petersburg and embraced in Kyiv by the Union of the Russian People and the editorial offices of the newspaper Dvukhglavyi orel [The Two-Headed Eagle], gave rise to a somewhat different interpretation from today’s standpoint.

No, I absolutely have no desire to compare the recent farcical story about the fictitious “boy crucified by Banderites” in Donetsk, purposefully promoted by Russian propagandists, with the murder of the real Andriusha Yushchynsky, which Black Hundreds members tried to exploit in order to accuse the entire Jewish population of the deadliest sins and to incite pogroms in Ukrainian cities and villages. These are different stories, different eras, different goals. But the methods?

In order to understand why Mykola Krasovsky became so caught up in this affair and why he refused to make any compromises with his conscience, we have to take at least a cursory glance at his biography.

Mykola Oleksandrovych Krasovsky was born in Kyiv in 1871 into the family of an Orthodox priest. Learning that his son wanted to join the police force, Rev. Oleksandr did not oppose his plans. He merely cautioned him always to follow his conscience, respect his good name, and abide by man-made laws, but first and foremost Divine law.

Krasovsky began his service activities as an assistant police inspector in Nizhyn, Chernihiv Gubernia. In 1907 he began working for the Kyiv municipal police, initially as a deputy, and later as acting head of the Investigation Department. His rapid career rise was due to his natural talents, his desire to dig down to the essence, adherence to principle, intransigence, and professional self-esteem, which did not allow him to work sloppily.

Within a short period of time, he solved dozens of high-profile crimes and established himself as one of the finest investigators. The book Kryminalnyi roschuk Kyieva [Criminal Investigation of Kyiv] offers the following description: “The criminal world of Kyiv noted that in the person of Krasovsky they had a serious opponent and that he should be avoided. Professional criminals of all stripes and colors understood that Krasovsky’s successful ‘discoveries’ were due to his superior professionalism and ability to ‘work’ with agents from their environment....”

One criminal group even decided to do away with the stubborn policeman and made plans to assassinate him. However, they failed to liquidate or intimidate him.

Meanwhile, danger lurked elsewhere. Some of Krasovsky’s colleagues were envious of his accomplishments, success, exacting nature, and intransigence. He became the target of numerous accusations of alleged misappropriation of funds seized from detainees, which were absolutely false. On top of it, he was sidelined.

The next half-year was marked by a number of unsolved crimes, and the municipal authorities were forced to reinstate Krasovsky in his former position. He was not angry, because he had adopted a good trait from his father: the ability to forgive. But he resolved to be more open in his work and closer to the inhabitants of Kyiv.

He began receiving visitors daily from 11:00 to 1:00 p.m. in the building housing the Investigation Department located at 38 Yaroslav Street, as well as in his apartment on 20 Malovolodymyrska Street (today: Honchar Street). An announcement about this practice was even published in the city directory. Kyivites flocked there gratefully because they met with understanding and a desire to help.

However, in 1910 the new head of the Investigation Department objected for some reason to Krasovsky’s leadership style, or, perhaps, he did not want to work alongside such a reputable and thoroughly mature professional. In short, they did not get along, and Krasovsky was transferred to the post of police inspector. He was occupying this position when unexpected news arrived from Kyiv in May 1911. On the governor’s orders, he was sent to carry out an independent investigation of the high-profile Yushchynsky murder.

The teenager had disappeared back on 12 March. That day he failed to return home for the night. His mother and stepfather initially thought that he had stayed over at his aunt’s. But the following morning the alarm was raised, and they reported his disappearance to the police and placed an ad in the newspaper Kievskaia mysl [Kyivan Thought].

Eight days later the mutilated, bound, and bloodless body of the boy was found in a cave near a brick factory belonging to the Jewish merchant Zaitsev in the Podil district. The body bore 47 stab wounds on the body caused by a large awl, including thirteen wounds on the temple and crown, as a result of which he lost blood and died.

The murder took place on the eve of Passover, or Jewish Easter, as people say. The city was instantly flooded with rumors that Jews needed the blood of a child or an adolescent for some kind of ritual. Black Hundreds newspapers even published announcements warning Christians to keep their children close because danger was imminent.

The prosecutor’s office tried to pin the murder on the foreman of the brick factory, 39-year-old Menahem Mendel Beilis, who had allegedly carried out a ritual killing in order to obtain Christian blood for preparing matzoh, which, according to Jewish tradition, was baked before Passover. This was utter nonsense and did not fit into any framework or canon.

Beilis’s designation as the killer was no accident. He lived near the site of the crime. He used to chase children away from the factory premises, where they played on the mixer for manufacturing the bricks. So, as someone who could be blamed for everything, he fit the bill.

Moreover, Beilis was meek, gentle, and a man of few words. No one was prepared to defend him. He was only distressed and declared monotonously that he was not guilty of anything. He begged to be allowed to return home to his children. At the time, he had no idea of the trial in which he would end up being involved.

Russian Black Hundreds organizations in Ukraine immediately put out their version of the ritualistic character of the murder. Their goal was to incite Ukrainians to antisemitic actions.

With the support of [Ivan] Shcheglovitov, Minister of Justice of the Russian Empire, they did everything in their power to prove Beilis’s guilt. Neither was the time frame for carrying out this action chosen randomly.

In February 1911 the Third State Duma had begun to discuss draft bills to abolish the Pale of Settlement, which sparked indignation and concern among antisemitic monarchist parties and Black Hundreds organizations, which threw all their forces against this project.

After exhausting all the antisemitic slogans customary for this period, they resorted to giving fresh impetus to an accusation dating back to medieval times that Jews, supposedly in compliance with the requirements of their faith, use Christian blood for their religious rites and ritualistic purposes.

The detectives from Berdychiv and St. Petersburg whom the authorities assigned to the investigation sought to prove the correctness of this theory. At the same time, fuel to the fire was added by people who were working vigorously to whip up antisemitic moods.

For example, the Kyiv Club of Russian Nationalists published and sold a great number of copies of a brochure entitled “What Ritual Killings Are.” The trial received wide publicity because of the public response in the press, both left- and right-wing. A special committee to defend Beilis was formed, and it was headed by Baron Ginsburg, the Brodsky brothers, and other authoritative figures.

The left-wing press published a protest entitled “To Russian Society (in Connection with the Bloody Slander against the Jews),” which was drafted by the writer Volodymyr Korolenko and signed by Mykhailo Hrushevsky, Maksim Gorky, Volodymyr Vernadsky, Aleksandr Kuprin, Serhii Yefremov, Dmitrii Merezhkovsky, Alexander Blok, Fedor Sologub, Leonid Andreev, and other intellectuals and civic figures.

The fabricated trial was condemned by practically all leading Ukrainian intellectuals. Hrushevsky called its initiators the “lackeys of tribal and racial hatred” and the “creators of a nightmarish fantasy and inhuman malice.”

The Ukrainian social-democratic group of Kyiv’s higher schools reacted the same way. The declaration that it made public noted: “The Beilis affair is not an issue of the Jewish people. It is an issue that torments all the stateless peoples who have been thrown into the prison of nations by the will of history.” Then the investigation faltered.

In involving Mykola Krasovsky in it and granting him special powers, the Kyivan authorities were relying on his experience and determination. As for Krasovsky, he now had an opportunity to demonstrate his superiority to his detractors.

After reviewing several erroneous theories, Krasovsky concluded that Andrii Yushchynsky was killed not by Beilis but by the members of a local gang that specialized in robberies.

The detective learned that the boy was friends with Yevgenii, the son of Vera Cheberiak, the leader of some Kyivan robbers. The boys had quarreled over some trifle, and Andrii supposedly vowed to tell the neighbors about Yevgenii’s robber-mother and her participation in recent robberies, as well as about the fact that she was storing stolen items in her house.

The woman heard about it. Her son had revealed everything, without thinking of the consequences. That kind of publicity was to no purpose. That is why Andrii Yushchynsky was killed, and it was done in such a way as to make it look like a ritual murder. The body was moved to the grounds of the brickworks owned by the Jewish merchant Zaitsev.

During the investigation, Krasovsky, trying to recreate the circumstances of the crime, explained that the thieves wanted to provoke a Jewish pogrom. This was convenient for them. Indeed, during the last pogrom in Kyiv in October 1905, Cheberiak’s apartment turned into a veritable warehouse of Jewish property looted by pogromists. The gangsters wanted to profit once again in the event of a new outbreak of pogroms.

At the detective’s demand, Vera Cheberiak was arrested, but she was released immediately “for lack of evidence,” even though, as it turned out, there was more than enough. Later, Krasovsky took her into custody again, so that she would not put pressure on witnesses. But, according to a written order issued by the district court prosecutor, he was forced to release her.

Krasovsky and the other detectives who were conducting the investigation in a way that inconvenienced someone, demonstrating integrity, and seeking to bring the real culprits to justice, were removed from the investigation. The Black Hundreds in Kyiv—members of the local organization “Two-Headed Eagle”—had a hand in this. It was they who began to spread rumors that Krasovsky had been bribed. Intense pressure was also brought to bear on those who had initiated his involvement in the investigation.

Krasovsky was sidelined from the investigation, and on 31 December 1911, he was dismissed from the police force. This was a real blow; a blow against his reputation as a genuine professional and his self-esteem.

Anyone else would have swallowed the bitter pill and become reconciled to the situation, but not Krasovsky. On the contrary, this turn of events spurred him to new actions. Soon he launched an independent, private investigation.

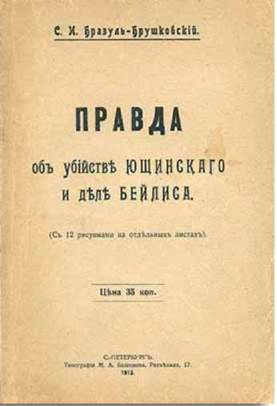

He was joined before long by the Kyivan journalist Brazul-Brushkovsky, who was conducting his own journalistic investigation. Of course, the leading role in this duo was played by the experienced detective. But not everything happened according to his scenario.

In late May 1912, a number of critical articles by Brazul-Brushkovsky about the Beilis affair appeared in several newspapers in Kyiv, garnering wide publicity. They even became the subject of discussions in the Kyiv Duma. But all this culminated in Krasovsky’s arrest.

His detractors, behind whom stood Chaplinsky, a prosecutor of the Kyiv judicial chamber, did not come up with anything better than to accuse the detective of various petty bureaucratic violations allegedly committed when he still held the position of bailiff in Skvyra County.

All this seemed quite funny. But Krasovsky had nothing to laugh about. The numerous interrogations and summons to investigators and to court took time away from his main investigation that he was determined not to stop.

His detractors did not cease their attacks on the uncompromising detective. They decided to approach from another angle: to exert psychological pressure on him.

During yet another session about the Beilis affair, at which Krasovsky decided to appear officially as a witness, his friends informed him that at this very moment the police had broken into his apartment and were questioning the members of his family. He was forced to request the court’s permission to leave the hall.

The sentence that was handed down, in this case, offered him some comfort and consolation.

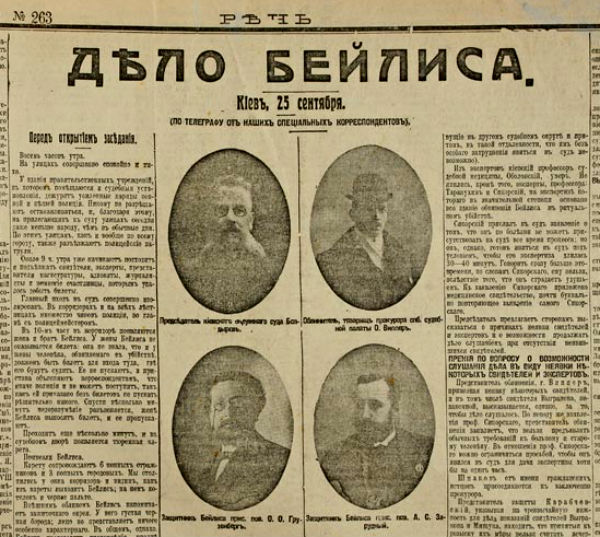

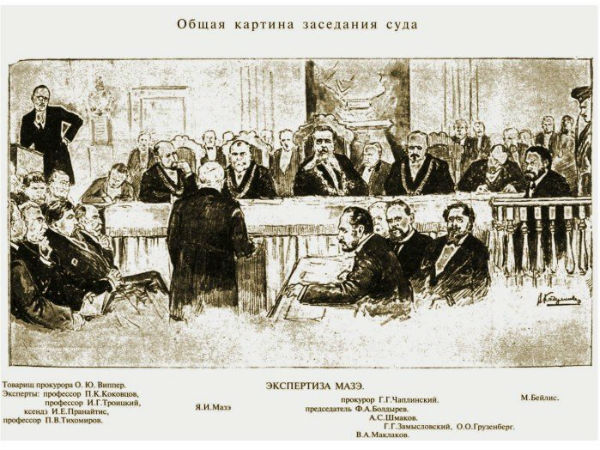

The trial took place in Kyiv in autumn 1913. The jury included only Ukrainians and Russians (for a complete picture, it would not be superfluous to note that all of them were carefully selected in order to achieve the correct vote; in particular, five of them were members of the Union of the Russian People). They had to answer two questions: Was it a ritual murder and was Beilis guilty of committing it?

On 28 October 1913, in keeping with the results of the investigation and statements of the parties at trial, the jury still found that it was a ritual murder.

As for Mendel Beilis’s guilt, the jury’s votes were equally divided: six and six, which meant that Beilis was acquitted.

In later references and reviews about this trial in some Russian publications, I have seen statements about these supposedly ordinary Russian peasants, that is, about the jury and the wisdom of the Russian people, to the effect that their wise decision prevented a possible massacre. Furthermore, Vera Cheberiak is identified as an ethnic Ukrainian member of the party of Ukrainian Socialist-Revolutionaries/Nationalists, which was allegedly headed by Volodymyr Vynnychenko. Everything is thus placed upside down; as in the past, so too now.

But let’s go back to the courtroom. After the decision was announced, Beilis was immediately released from custody. The hall met this forced verdict with a standing ovation. At last the unfortunate man, following two and a half years of torment in Lukyanivka prison, where he nearly froze off his feet and lost his health, was freed.

But Krasovsky, together with the lawyers, journalists, and representatives of the progressive public, did not stop there. They could not accept the fact that the murder was recognized as a ritual one. It was an overtly political decision. After all, the antisemites sought to prove not so much Beilis’s guilt as that of the entire Jewish people. The experienced detective was a hundred percent sure that this was a crime of the first water.

Krasovsky continued to search for evidence of this and still sought to bring to justice the real guilty parties and witnesses to the murder, in spite of the fact that some of them conveniently left Kyiv and disappeared in other cities and even countries. He stopped at nothing, even at traveling to the United States to locate one of the most important witnesses in the case: Vera Cheberiak’s neighbor, Adele Ravich.

Krasovsky learned that the woman had allegedly seen Andrii Yushchynsky’s corpse in Cheberiak’s house. One time she blurted this out in her neighborhood. On the eve of the trial, she suddenly left Kyiv and went to America with her husband. It was even rumored that their journey had been organized by Kyivan members of the Black Hundreds, for fear that the undesirable witness could be called to give testimony.

The American Jewish Committee assisted the former policeman in his search in the U.S. Through their joint efforts, Adele Ravich was found in a small town.

Krasovsky had to use all his detective experience and eloquence to get the woman to agree to give at least written testimony. After notarizing it, he returned to Kyiv in an optimistic mood; he was hoping to reopen the investigation. But it was all in vain. The court found that the evidence was insufficient to order a new trial.

After learning about this trip and that Krasovsky was not abandoning hope for a fair trial, the Kyiv underworld, together with local Black Hundreds members, began to follow him. In order to avoid unnecessary danger, he went to Konotop for a while; he had decided to take a break and resolve some personal problems. However, he never stopped thinking about the Beilis case.

After the news of the overthrow of the autocracy in February 1917, Krasovsky returned to Kyiv. The Ukrainian Central Rada, which was seeking cadres to recruit them to its side, invited him to serve as an officer who welcomed the idea of national statehood. His reputation as a true professional and honest, principled, and incorruptible individual played a role here. This was attested by what various people said about him. And the impressions of his involvement in solving well-publicized cases in Kyiv, particularly his role in the investigation of Andrii Yushchynsky’s murder, were still fresh in people’s minds.

Krasovsky was immediately appointed commissioner of the Criminal Investigation Department of the Kyiv police. He held this position until June 1918, and during this period he did a lot to fight crime. But his urgent, daily tasks made it impossible for him to devote any attention to the case that for years had given him no rest.

The change of power—the proclamation of Pavlo Skoropadsky as Hetman of the Ukrainian State—was another impediment.

Krasovsky did not accept these changes. He became a member of an underground organization that fought against the special services of the Austro-German troops stationed in Ukraine under the Brest-Litovsk Treaty, and he was a member of the outlawed Committee to Save Ukraine. The committee was called upon to prepare an armed uprising and normalize the situation in the country.

Soon, however, German counterintelligence arrested Krasovsky, along with other like-minded people. He was sentenced to two years in prison by a German military field court. However, he ended up behind bars for only six months.

After the abdication of Hetman Skoropadsky, Krasovsky and other prisoners were released in December 1918. Soon he was invited to work in the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the UNR.

Restoring old contacts, he accidentally learned that in recent months Vera Cheberiak was caught trying to sell weapons and was shot for this. And one of the main killers of Andrii Yushchynsky, a man named Synhaievsky, was arrested in another case. In response to a suggestion to tell the whole truth about Yushchynsky’s murder in exchange for a pardon, he said: “If I talk, my people will kill me.” He was shot anyway.

Despite this, Krasovsky did not abandon hope for an open and fair trial under the new government, which was bound to prosecute all criminals and revise the political decision about the ritualistic nature of the murder.

Owing to his new duties, he was unable to resume the investigation, nor was it part of his responsibilities. Taking into account his extensive experience of operational investigative activities, the military command sent Krasovsky to the Intelligence Department of the General Staff of the UNR army and appointed him head of the Information Bureau, the main working body of military intelligence and counterintelligence of the armed forces of the republic.

In this position he did a lot to set up intelligence work and developed a number of normative documents, embedding in them his vision of this specific activity and focusing on the main features of national intelligence and counterintelligence personnel. This work continued until the Ukrainian government and military units relocated to the territory of Poland.

Abroad, Krasovsky was engaged for some time in organizing intelligence and counterintelligence activities. He later retired gradually and settled in Rivne. He now had plenty of time for reflection and taking stock of his eventful life. Musing on the past, he repeatedly thought back to the Beilis affair. Even though the main figure had already immigrated with his family to the U.S. and fate had punished some of the perpetrators of the murder of Andrii Yushchynsky, he had not given up hope that the case would be reviewed one day. Armed with this belief, he set about writing his memoirs.

Recently I came across the almanac Yehupets. One of its issues contains an article by Yefim Melamed in which I found fragments of Mykola Krasovsky’s correspondence with Hryhorii Kaminsky, the secretary of the Rivne Jewish Center.

In a letter dated 7 July 1927 Krasovsky wrote:

“On the basis of our personal conversations, I ask you to trouble yourself to grant me the opportunity to complete and publish my memoirs about the Beilis affair. These memoirs have the ultimate goal, in one form or another, of achieving a dispassionate review of this case, which should finally, someday, acquire its inherent name: ‘the monstrous provocation of the last tsarist government of Russia,’ not ‘the Beilis affair.’

Seeking at the same time to overturn the first part of the verdict in this case, which confirmed the existence of ritual murders in order for Jews to use Christian blood for religious needs, I believe that the reasons and methods, on the basis of and thanks to which the Russian government was acting at the time, and also the circumstances about which I was deprived of the opportunity to speak at the trial, as well all that was discovered by me later, after the trial, should certainly rouse considerable interest throughout the civilized world and shed light on this dark affair.”

These memoirs could certainly have shed light on some new circumstances and the author’s fate. Unfortunately, neither traces of the manuscript in the archives nor any information about the fate of Mykola Krasovsky have been found to date. At the same time, his participation in this trial, inspired by reactionaries of the Russian Empire, demonstrated that, despite intense pressure, there were honest, caring, principled, and noble people who were not afraid of either the authorities, or the Black Hundreds, or members of the criminal world, and instead stood on the side of law, justice, and human values.

And Krasovsky was not alone. At a certain stage of the trial, the chairman of the Kyiv district court, who was considered unreliable, was replaced. Let us recall that among the Kyiv prosecutors there was no one who volunteered to act as state prosecutor, and the Minister of Justice had to second a prosecutor from St. Petersburg for the trial. Not a single Orthodox priest agreed to act as an expert for the prosecution.

We should doubtless revisit the events of our past history more often and attempt to look at them from a slightly different angle, and analyze, reinterpret, and draw conclusions.

Олександр Скрипник

13 March 2018

Oleksandr Skrypnyk,

Researcher specializing in the history of the secret service

Istorychna Pravda’s “Shalom!” media project, which explores the Ukrainian-Jewish dialogue, is made possible by the Canadian non-profit organization Ukrainian Jewish Encounter.

Translated from the Ukrainian by Marta D. Olynyk.

Edited by Peter Bejger.

NOTE: UJE does not necessarily endorse opinions expressed in articles and other materials published on its website and social media pages. Such materials are posted to promote discussion related to Ukrainian-Jewish interactions and relations. The website and social media pages will be places of information that reflect varied viewpoints.