Mykola Riabchuk: Our society is nearing normalcy

The "Encounter" prize is sponsored by the Ukrainian Jewish Encounter, a Canadian charitable non-profit organization, with the support of the NGO "Publishers Forum" (Lviv, Ukraine).

In the week leading up to the award, the influential online publication Zbruc ran interviews conducted by journalist Marta Konyk with the three members of the independent international jury for the "Encounter" prize — Liliana Hentosh, Mykola Riabchuk, and Marko Stech. The second interview is with jury head Mykola Riabchuk of Ukraine.]

Originally appeared in Ukrainian @Zbruc.eu

Promoting understanding between Jews and Ukrainians and awareness of each other's historical experiences and narratives is the goal of a new literary prize established by the Ukrainian Jewish Encounter, a Canadian charitable non-profit foundation, in cooperation with the NGO "Publishers Forum" in December 2019.

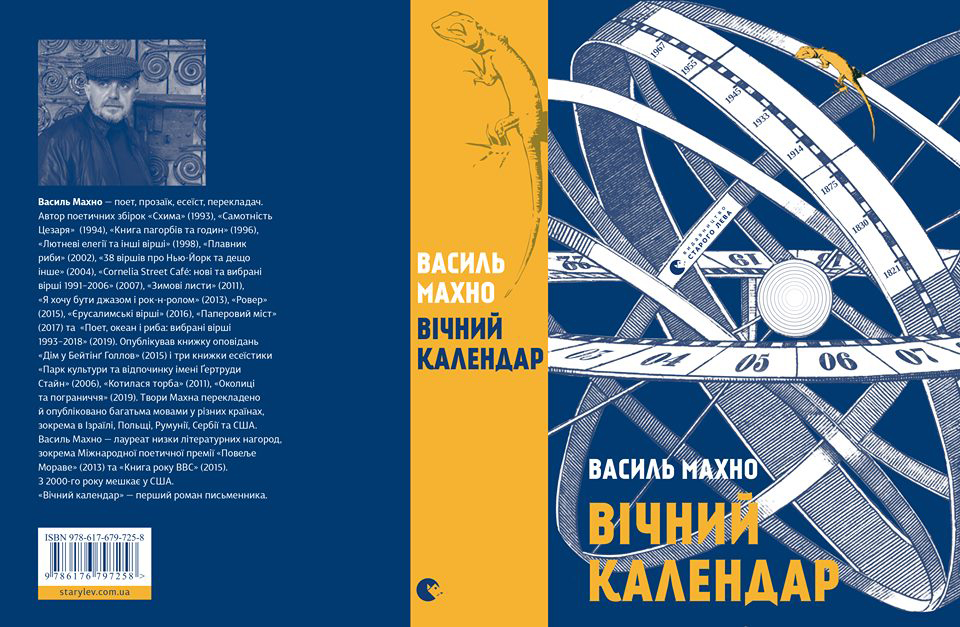

The first award winner was the book Eternal Calendar by Vasyl Makhno, a poet, novelist, essayist, translator, literary critic, and regular contributor to the Zbruc. This year, the prize is awarded for nonfiction, and who will win is an intriguing question on the eve of the BookForum festival in Lviv. The jury consists of Mykola Riabchuk, Liliana Hentosh, and Marko Robert Stech.

Before the results were announced, we talked with Mykola Riabchuk about the advantages of winning this prize, promising authors, and cultural appropriation fostered by the "Encounter" prize.

You once said that, as a reader, you now prefer specialized professional literature, i.e., the kind you have to read as a jury member. What is your personal benefit or satisfaction from reading only those books that you have to judge? Well, except that they have already passed certain selection, and you do not need to spend time to discover unnoticed works.

Today I am a jury member for two prizes. One of them, the "Angelus," is awarded by the city of Wroclaw to writers from Central Europe. More than twenty countries submit their works in Polish translations for this prize. The second one is actually the "Encounter: The Ukrainian-Jewish Literary Prize." The amount of work is, of course, smaller here because we are already working with ten preselected books, which makes our task easier. Each of these works is interesting because I get the cream of the crop. I may like some of them more than others, but each of these books bears a mark of quality. So, this is a favorable position, and I am happy about this opportunity.

At the same time, it is a major workload and responsibility because you are constantly tormented when selecting the best. Each book has its advantages, and we often have to compare apples and oranges, i.e., works that are not always comparable. This is when taste comes into play, and we argue with other jury members.

It is no secret that reaching an agreement is not easy. We need to find flaws to reject publications and prevent them from advancing to the next round. However, it is nice that we have so much good literature. In other words, this job is interesting and gratifying but also responsible and even painful at times.

There is some good and unexpected news — we actually have many books on Ukrainian-Jewish topics. I have always believed that we should treat all ethnic cultures in Ukraine as part of Ukrainian culture. In other words, it is not Jewish, Russian, or Tatar literature in Ukraine but Ukrainian literature created in other languages and by people of other ethnic origins. I prefer an integrated approach that views culture as everything that happens in this territory. An important clarification is in order: everything that happens in our context but not against our context.

I think it is not accidental that this prize was established. Obviously, it took us a long time to reach this point, and it could have perhaps been inaugurated earlier. However, 2014 was, on the one hand, a decisive year, a highly dramatic one, because this was when the Russian aggression and the Russian-Ukrainian war began. On the other hand, it was also a year that suddenly opened our eyes to the fact that we have our Russians, our Jews, and our Tatars. These are not just people who live here — these are people who are with us and are, like ourselves, patriots and defenders of Ukraine.

Ukraine has never had its own state, so all the minorities that lived here were reluctant to identify with Ukrainians or the Ukrainian cause. Well, that's understandable. Every minority is unprotected and vulnerable, and it doesn't make much sense to assimilate with people as weak as you are. It is always better to side with the stronger party; otherwise, you will not hold out — this is the law of survival.

Therefore, Ukrainians had certain problems with all minorities, which, at best, adopted a neutral position in all these Ukrainian national liberation struggles, movements, and so on. This is an objective truth, and I do not blame anyone. This is how it was, and I understand why. The situation began to change when Ukraine became independent. Obviously, there were exceptions before that. For example, when the process of Ukrainization started in the 1920s, there was a chance that an autonomous, if not independent, Ukraine could emerge.

Do you mean the interwar period?

I mean the 1920s, the period of Bolshevik Ukrainization. Obviously, this was a push that came earlier from the Ukrainian National Republic (UNR) and the national liberation struggle, which the Bolsheviks had to accept as a fait accompli. They could not cross out this period and return Ukraine to tsarist times when it was possible to say that the Ukrainian language did not and could not exist. They had to recognize Ukraine and grant it autonomy. A certain national and cultural revival followed. Minorities emerged that became involved in Ukrainian culture on the Ukrainian side. This did not last long, unfortunately, although it looked promising.

This process resumed after Ukraine became independent. In 2014, Jewish activists denied the Kremlin's fabrications that there were fascists on the Maidan, a frightening coup was occurring, antisemites in Ukraine, and so on. The world, in principle, listened not so much to our voice — because ours could be a dubious voice — but to the voice of Jewish activists. They made a statement of tremendous import. So, this was a two-way street. Minorities, in particular Jews, but also Russians, largely sided with Ukraine. This prompted Ukrainians to suddenly discover that we have these minorities and that they, too, are citizens and patriots of Ukraine. I would say that we knew we had them even earlier. Theoretically, we understood that Ukraine is a multi-ethnic country and a political nation and that everyone here has the same rights and so on. However, this was purely rational knowledge; it was not internalized.

What happened to Ukrainians themselves during the Revolution of Dignity that preceded this understanding? What came from the Ukrainian side that prompted Jews, Russians, and Tatars to react and later enabled Ukrainians themselves to understand and feel more deeply that these minorities were theirs?

I think this emotional awareness and acceptance of multiethnicity did not emerge out of a vacuum. It took two and a half decades — when we lived side by side and had the opportunity to look closely at each other — to reduce the pre-existing prejudice fuelled by the Soviet government, which was interested in inciting distrust, suspicion, and xenophobia. This has decreased over the years of independence.

The revolution did not change us radically but acted as a catalyst for the processes that had been developing very slowly. Gradual comprehension of each other and cooperation between Ukrainian intellectuals and those of Jewish, Russian, and Tatar backgrounds began before independence in Ukraine. We know about Ivan Dziuba's speech in Babyn Yar in the 1960s and many other significant events. They laid the groundwork. The revolution and the war were the triggers that accelerated the processes of mutual comprehension, awareness, and trust, which does not emerge out of nowhere.

We need to have the experience of working together and to know that these people can be trusted. I really like how it finally happened, although you can always complain about why it did not happen sooner. What prevented us from understanding earlier that we indeed had Crimean Tatars and that this was the anniversary of their deportation, which we began to commemorate after 2014? We mentioned it in passing, but it was not a national event in Ukraine.

Now, at the end of May, we all know about this important day. We see the relevant banners, posters, city lights, and publications in the media. We are, of course, late, and we are also paying the price for this, but it's still good that this realization has taken place. And I put these events in the same context. In particular, the "Encounter" prize has emerged here naturally. It works in line with these processes and stimulates them.

You have repeatedly described how impressed you are by the number of books the "Encounter" prize has brought to your attention. What about the quality of nonfiction literature?

I read only the ten publications that I received for the competition. All of them are very good. I was familiar with some of them even before the award because these are notable books. I read two of them in English: East West Street by Philippe Sands and The Anti-Imperial Choice: The Making of the Ukrainian Jew by Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern.

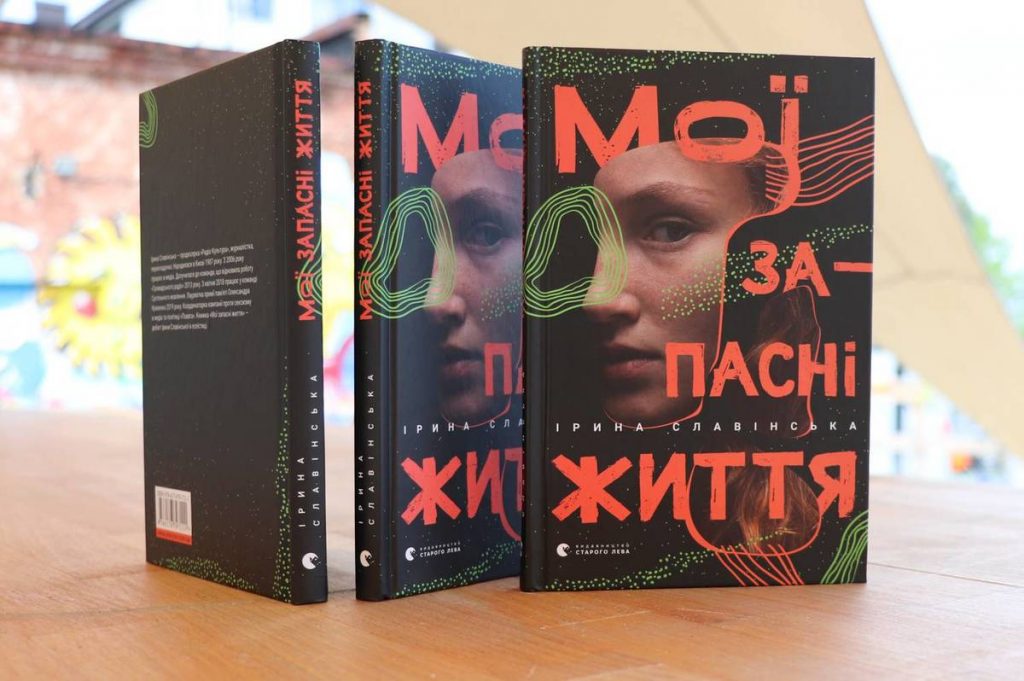

I also managed to buy and read Iryna Slavinska's book My Spare Lives (Moi zapasni zhyttia), which is a wonderful collection of lively essays. Of course, I was already familiar with Vasyl Makhno's Suburbs and Borderlands (Okolytsi ta pohranychchia), because I had the opportunity of reading it when I was on the jury of the Yuri Shevelov Prize for essays. In general, I believe that Makhno and Slavinska are our hope.

Other books were unknown to me but became a revelation. For example, I was happy to pick up Andriy Kozytsky's Shadows of the Jewish City. A Guide to Lviv (Tini yevreiskoho mista. Putivnyk Lvovom). Obviously, one can question the way the material is presented in this text. The author seems to reproduce clichés sometimes. However, the publication itself is very good, and it's great that it has appeared. We need these kinds of guides not only in Lviv but throughout Ukraine.

Iryna Meleshkina's Wandering Stars in Ukraine. Pages from the History of the Jewish Theater (Mandrivni zori v Ukraini. Storinky istorii yevreiskoho teatru) was a book I flipped through and partly read earlier and now had the opportunity to read it in full. This is a solid study of the entire history of the Jewish theater in Ukraine from the turn of the twentieth century until the present. It is well-illustrated, but the quality of the illustrations themselves is not perfect due to technical issues.

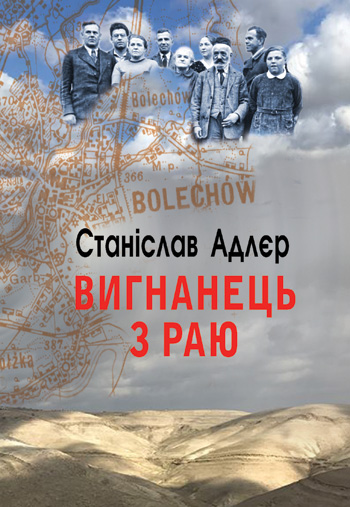

The two books of memoirs are very different. I read them only thanks to the competition as I had never seen them before. These are A Jew Again: From Bolechow to Communist Poland to the Jewish State by Shlomo Adler and In Other Times. Young Years in Eastern Galicia (In einer anderen Zeit. Jugendjahre in Ostgalizien) by Soma Morgenstern.

Morgenstern writes much more professionally. He is clearly a professional writer. His memoirs are a literary work attractive in their professional artistry, while Adler wins you over with a certain naivety, innocence, openness, and immediacy. These are not the memoirs of a professional. Rather, they are put together so well and written precisely to appear unprofessional to the point of being touching. Obviously, Adler has inherent spontaneous talent.

The two handbooks for secondary school students, Pages from the Jewish History of Ukraine (Storinky yevreiskoi istorii Ukrainy) and Pages from Ukraine's Jewish Art (Storinky yevreiskoho mystetstva Ukrainy), are books that resonate in a way with Meleshkina's work, even though they are not scholarly monographs, i.e., they do not present original research. These publications are a good compilation, a collection of already available material, which is definitely needed. The problem is with incorporating them into the scholarly process and making them relevant and effective precisely as handbooks. How else can this multicultural Ukraine be built if not with the help of such textbooks?

The two handbooks for secondary school students, Pages from the Jewish History of Ukraine (Storinky yevreiskoi istorii Ukrainy) and Pages from Ukraine's Jewish Art (Storinky yevreiskoho mystetstva Ukrainy), are books that resonate in a way with Meleshkina's work, even though they are not scholarly monographs, i.e., they do not present original research. These publications are a good compilation, a collection of already available material, which is definitely needed. The problem is with incorporating them into the scholarly process and making them relevant and effective precisely as handbooks. How else can this multicultural Ukraine be built if not with the help of such textbooks?

The tenth book, which I would like to give a separate mention here, is Yuri Skira's They Were Called Upon: The Monks of the Studite Order and the Holocaust (Poklykani: Monakhy Studiiskoho ustavu ta Holokost). This serious academic treatise by the young author is obviously not without certain mistakes and flaws. However, it is the first thorough study of this type, and the author is a young scholar with great potential. I think it is wonderful that his work is in the top 10.

The collection of these excellent books is already a small library, especially if you remember to include last year's finalists. Future competitions will add to this library. I suppose that not all the best books reached the top 10 because there was a preselection, which is always somewhat subjective. In any case, we have something to work on here.

Not all publishers may have heard about this prize. It is now only in its second year and is being awarded for nonfiction for the first time. How do you see the evolution of the prize and its role in the Ukrainian literary and social process in general?

First of all, I don't think publishers are unaware of this prize. It has been advertised and covered in the media. And this is a prize that comes with a significant financial value: it is awarded to both the author and the publisher to provide an incentive. So, there is practical interest here, but recognition itself is important because it is symbolic capital.

The Ukrainian-Jewish literary prize attracts attention with book quality and its very character — it is quite new and unusual. There was no such thing in Ukraine before, and the names are very respectable. The mere presence of Vasyl Makhno, Philippe Sands, or Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern already attracts those who know a little about culture — or Iryna Slavinska, who is a very popular journalist. Not only does the prize help promote specific books in Ukraine, but specific well-known figures also promote this prize with their presence. I am delighted to see them on the nominee list, even if they do not win the prize.

Vasyl Makhno was the winner last year when the prize was awarded for the first time.

Yes, Eternal Calendar is an excellent novel. I am not a member of the "Encounter" prize jury for fiction, but I have read this book. I think this is one of the best novels in Ukrainian literature. It deserves all possible awards — perhaps even some future awards because this is a phenomenon in Ukrainian culture. The Jewish theme is not the main one in the novel. However, it is presented quite thoroughly; it occupies an important place and is nicely and interestingly covered. So, that's great. We have Vasyl Makhno on the list again. He seems to have a certain tendency.

Vasyl Makhno also participated in the Agnon Literary Residence in Buchach, and I interviewed him for Chytomo about the outcomes of this residence. His next novel will also deal, to some extent, with Jewish themes and with the figure of Shmuel Agnon. At the same time, the biblical part will be just as important in the new text.

I'm glad you mentioned Agnon and this entire cultural layer, which really needs to be mastered little by little. All of this, in principle, took place in Ukraine, on our territory. To a larger or lesser extent, it is part of our history and culture. There is no reason to be overly shy about this. These things are Ukrainian to the extent that we can comprehend them, embed them into our context, and then proceed from them, making them part of our heritage. It depends on us how much these things will be Ukrainian.

We once had a fascinating discussion with Professor Grabowicz [George G. Grabowicz, Professor of Ukrainian Literature, Harvard University—Ed.] on this topic. We were with a group of people who debated how much [Nikolai/Mykola] Gogol can be considered a Ukrainian writer. He very wisely said that Gogol would be a Ukrainian writer to the extent that we would be able to write about him, incorporate him into the Ukrainian world, and build on him. It's in our hands, I think.

The same goes for Agnon and Bruno Schultz, although they also belong to other cultures. For a writer, language is decisive, no matter what we say. An author is first and foremost an author of the literature in whose language he writes — I have no doubt about that. However, we do not rule out hybridity. He can belong to both. He can also be part of our heritage if we imagine it and manage to incorporate this author into it.

What Makhno does is very important because he incorporates [certain figures] into Ukrainian culture. I think he will succeed in doing the same with Agnon. No matter whether Agnon or Paul Celan themselves would wish this to happen, it is up to us to use their legacy. We can adapt them to Ukrainian realities and build Ukrainian culture on the basis of this heritage.

Imagined history and imagined connections are no less important in culture than real ones because the boundary between the real and the imaginary is very much blurred here. After all, all of culture and literature is imaginary and imagined. If a writer such as Makhno imagines himself an heir of Agnon and manages to show it convincingly in his fiction works, then glory, honor, and praise to him. He will receive the Nobel Prize like Agnon did. It will be logical, and I will be the first to write about this genealogy and this connection — why not?

We have, after all, the example of the Czech Republic, which includes Franz Kafka in all anthologies of Czech short stories. This does not mean that he is removed from Austrian, German, or Jewish culture. Writers are very often cosmopolitan in that they belong to different cultures. Again, the question here is how capable that culture will be of mastering and appropriating a particular figure.

The "Encounter" prize actually helps with this kind of appropriation. In addition to Ukrainian authors, we have a number of books written by foreigners and translated into Ukrainian. These works have already become part of Ukrainian culture, consciousness, Ukrainian-Jewish ties, and hence, Ukrainian because these ties are part of us. I suppose there could be arguments about whether the prize had to be limited to Ukrainian authors and publications or whether foreigners could be allowed. I think the right decision was made.

Incidentally, our decision is of the same type I see in the "Angelus" prize that Wroclaw established for writers from Central Europe, writers coming from a large number of countries, from Germany to Russia, from the Balkans to the Baltics. The only condition is that their works must be published in Polish. That is, Polish writers who naturally write in Polish and foreigners from this region whose works have been translated in Poland all become part of Polish culture. They remain Croats, Serbs, and Estonians, but at the same time, they are included in the Polish context. That is, they are all in the same field, competing for the same prize, analyzed, compared, and contrasted with each other in the same dimension. A certain synthesis thus takes place, and it works for Polish culture.

Incidentally, our decision is of the same type I see in the "Angelus" prize that Wroclaw established for writers from Central Europe, writers coming from a large number of countries, from Germany to Russia, from the Balkans to the Baltics. The only condition is that their works must be published in Polish. That is, Polish writers who naturally write in Polish and foreigners from this region whose works have been translated in Poland all become part of Polish culture. They remain Croats, Serbs, and Estonians, but at the same time, they are included in the Polish context. That is, they are all in the same field, competing for the same prize, analyzed, compared, and contrasted with each other in the same dimension. A certain synthesis thus takes place, and it works for Polish culture.

Of the fifteen competitions that have already taken place, only one was won by a Polish author. This does not mean that Poland loses. True, the city of Wroclaw pays a significant amount to foreigners, but it pays off in a cultural sense. They hold a festival attended by the participants of the literary competition. All finalists are simultaneously invited to the ceremony, which is extremely important for Wroclaw as a cultural and tourist center.

Our "Encounter" prize similarly fits into the Lviv Publishers' Forum, and it's great. A prize makes sense when it works in a public space and has an award ceremony and some intrigue that comes along with it. Winners and finalists give interviews and professional lectures. All of this strengthens the cultural process. We have just begun to learn to do so.

There have always been many different prizes in Ukraine. In particular, the Writers' Union has had multiple prizes that have not performed well. Nobody knows about them, and nobody hears about their winners. Even the Shevchenko prize still does not receive due publicity, even though it seems to be the most significant [literary] award in Ukraine.

Your fellow jury member Liliana Hentosh spoke about the "Encounter" prize in an interview and said that the topic of Ukrainian-Jewish understanding is relevant now because there is a new generation of Ukrainians and Israelis who want to look differently, for example, at the figure of Metropolitan Andrei Sheptytsky and his relationship with the Jews. His life is now being carefully studied from this angle in Lviv and Ukraine, and active efforts are again being made to have Sheptytsky recognized as a Righteous Among the Nations.

Of course, you have rightly mentioned here the situation with Metropolitan Sheptytsky and, in general, the problem of new knowledge and old knowledge, which also has its inertia. I suppose that this old knowledge played a role in the Sheptytsky case. There was no objective reason to deny him the recognition as a Righteous Among the Nations back then. Of course, there was strong resistance from Soviet agents, who, on the contrary, tried to paint an unambiguously black and antisemitic image of Ukrainians.

Naturally, any positive mention of Sheptytsky or anyone else went against their interests. Enormous damage has been done, and it is hard to overcome these stereotypes because there is a pro-Moscow Russian lobby and people who think stereotypically in different environments. And this is a colossal job to try and fight it.

However, time passes, and in this sense, there is hope for new generations that no longer have old stereotypes and that are easier to reach with new knowledge. In this sense, all these books and activities are needed precisely to form an unmuddied and unobstructed view of complex problems.

In no case can the past or the present be idealized. There must be some sort of clean-up to remove the garbage that was deliberately produced in Soviet times. It was hate speech disguised as a struggle against bourgeois nationalism or cosmopolitanism. In all these cases, it was a fight against national identity — either Jewish, which was stigmatized as cosmopolitan, or Ukrainian, against which the Soviets waged an anti-Ukrainian campaign nicely packaged and mystified as a fight against Ukrainian bourgeois nationalism. There was never a fight against Russian bourgeois nationalism.

We went through all this, and it left its mark — perhaps not on my milieu but presumably on a large part of the population. I think it also played a role in how we as a society went through 1991 and how we voted in the presidential elections then. In fact, we are still struggling with this legacy.

Now more than ever, we need the kind of books that are awarded the "Encounter" prize. The activities we do together bring our society closer to normalcy. No society is completely normal, i.e., as we would like to have it, close to an imaginary ideal, but these things push us in that direction.

Interviewed by Marta KONYK.